61 Cardiac Valvular Disorders

• In patients evaluated in the emergency department for chest pain, dyspnea, syncope, arrhythmia, or shock, the possibility of valvular heart disease should be considered.

• Emergency echocardiography is essential in elucidating whether acute valvular pathology is responsible for hemodynamic collapse in a patient with cardiogenic shock.

• An asymptomatic patient with a grade 2/6 systolic murmur needs no further work-up.

• Diastolic murmurs are always pathologic and require echocardiography.

• Endocarditis prophylaxis is recommended only for dental procedures and no longer needed for gastrointestinal or genitourinary procedures.

Epidemiology

The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology has published guidelines for assessment, diagnostic testing, and medical and surgical treatment of VHD.1 However, there are still many practice guidelines that are based on observational studies instead of randomized controlled trials. Recent trends in care include identifying subgroups of asymptomatic patients who may benefit from surgical intervention, valvular repair rather than replacement, and minimally invasive or percutaneous options.

Pathophysiology and Presenting Signs and Symptoms

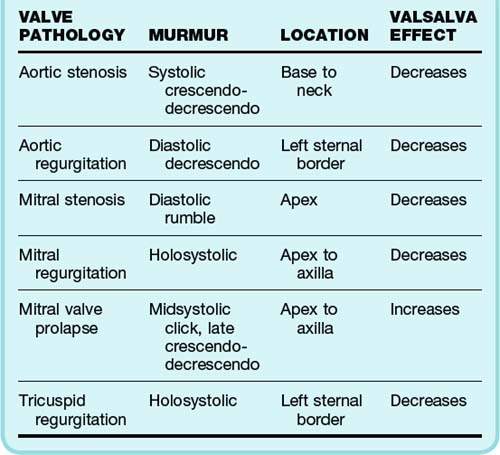

Physical examination establishes where the murmur occurs within the cardiac cycle and its location, duration, and intensity. Murmurs are classified as systolic, diastolic, and continuous. Systolic murmurs are further subclassified into holosystolic (pansystolic), midsystolic, early systolic, and late systolic. Clicks can be heard from the snapping shut of diseased valves. Diastolic and continuous murmurs are nearly always pathologic and require investigation, even in the absence of symptoms. Although many systolic murmurs merit investigation, especially those associated with symptoms, the majority of systolic murmurs do not signify valvular disease.2 A summary of the typical findings in the major valvular abnormalities is presented in Table 61.1.

Patients with midsystolic murmurs, grade 2 or less, and no associated findings or symptoms do not need any further work-up other than a history and physical examination. Aortic sclerosis is the most common defect found in these patients and requires no other intervention. However, patients with holosystolic murmurs, grade 3 murmurs, and diastolic or continuous murmurs should undergo further work-up with echocardiography.3 Some of these patients may eventually need cardiac catheterization if valve repair is planned. In patients with cardiopulmonary symptoms, detection of any new murmur warrants further investigation. The lack of a murmur in a patient with prosthetic heart valves may be pathologic and also requires further evaluation.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

A new diastolic murmur in a patient with chest or back pain should raise suspicion for aortic dissection and requires urgent testing and consultation, as well as control of the heart rate and blood pressure.

Patients with valvular heart disease may become hemodynamically unstable with rapid atrial fibrillation and require cardioversion.

Infectious endocarditis should be considered in all patients with a prosthetic valve and fever. Blood cultures and empiric antibiotics are indicated.

Beside echocardiography should be performed in patients with shortness of breath who have recently undergone prosthetic valve replacement to rule out pericardial tamponade.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

A careful murmur examination should be performed in patients with chest pain. Individuals with severe aortic stenosis are dependent on preload to maintain systolic blood pressure, and treatment with nitrates can cause severe hypotension.

Patients in cardiogenic shock from acute mitral regurgitation, aortic regurgitation, or prosthetic valve dysfunction may not have an appreciable murmur and require emergency echocardiography. These conditions are treated surgically and will require cardiac surgery consultation.

Emergency physicians need to recognize that the absence of a murmur or mechanical heart sound is pathologic in a patient with mechanical heart valve prosthesis.

Be vigilant in patients with a bicuspid valve and chest pain because of an increased risk for aortic dissection in these individuals.

Specific Valve Lesions

Aortic Stenosis

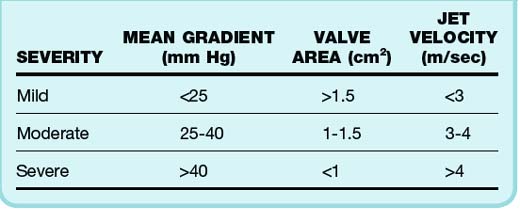

The degree of aortic valve disease is based on several factors4 (Table 61.2). Such assessment may be inaccurate and underestimate valve area and jet velocity in patients with impaired cardiac output. Progression of AS is usually quite slow, with symptoms taking decades to become manifested in most cases. An average 0.1-cm2 decrease in valve area occurs per year.5 The left ventricle is faced with systolic pressure overload and compensates through hypertrophy of the left ventricular (LV) wall. Normal chamber volume is maintained, but with increased wall thickness. The hypertrophic wall may lead to decreased coronary blood flow, even in the absence of stenosis and angina. Diastolic dysfunction and heart failure symptoms may also be present. These patients are dependent on forceful atrial contraction to maintain elevated LV end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) to overcome the obstruction to outflow. Therefore, individuals who have AF and AS may suffer hemodynamic consequences from loss of the atrial kick.

Auscultation reveals a systolic murmur associated with diminished and delayed carotid pulses (parvus et tardus), a sustained LV impulse on palpation, and a decreased or absent aortic component of the second heart sound (S2). Parvus et tardus may not be readily apparent in the elderly because of decreased compliance of the aging arterial vessels. Chest radiography may show normal heart size (remember concentric LVH) with rounding of the LV border. ECG can show LVH with a repolarization abnormality, which is seen in 85% of patients with severe AS. Echocardiography is indicated every year for patients with severe AS to assess the severity of the AS, wall thickness, and LV function. Exercise stress testing may lead to complications in patients with symptomatic AS and should not be performed.6

No medical treatment has been shown to decrease progression of disease in the leaflets, although statins are currently being studied. Significant care should be taken when treating these patients with preload-reducing agents (nitrates) because the sudden decrease in preload can cause severe hypotension, which in turn can lead to decreased coronary flow and worsen ischemia and shock. Cardiac catheterization is indicated in patients who have a discrepancy between the clinical complex and the results of echocardiography. Patients in whom cardiac surgery is planned need to undergo cardiac catheterization to assess the need for a concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) procedure. The average mortality in patients who undergo aortic valve replacement (AVR) is 3% to 4% and, when associated with a CABG procedure, 5.5% to 6.8%. Percutaneous valvuloplasty is the use of a balloon to fracture calcium deposits in the leaflets. It results in immediate improvement in valve gradients; however, restenosis occurs in 6 to 12 months, and it is therefore not recommended for definitive treatment. This procedure has been used as a temporizing measure in patients who are not initially AVR candidates. Procedures are now available that allow percutaneous AVR in such patients.7

Aortic Regurgitation

Multiple conditions can cause aortic regurgitation (AR); the most important for the emergency department (ED) physician are aortic dissection, trauma, and endocarditis.8 Patients with congenital bicuspid valves are also at risk for both AI and dissection. Rheumatic heart disease is still the most common cause of AR worldwide. Cardiac examination in patients with AR reveals a murmur during diastole, more low pitched and associated with a widened pulse pressure and displaced LV impulse. Eponyms associated with AR include Corrigan pulse (rapid rising pulse that falls rapidly), Quincke pulse (capillary pulsations at the base of the nail when pressure is applied at the tip), and the Duroziez sign (to-and-fro murmur over the femoral arteries).

Patients with acute AI have a sudden large regurgitant blood volume. Because the heart has not had time to compensate, large rises in LVEDP and left atrial pressure and a decrease in stroke volume occur.9 Patients are seen in shock, with hypotension and pulmonary edema. If the LVEDP and aortic pressure gradients are close enough, decreased coronary blood flow and myocardial ischemia can develop. This low gradient may make it impossible to hear a murmur. Emergency bedside echocardiography with color flow Doppler imaging is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

Mitral Stenosis

The normal mitral valve has an area of 4 to 5 cm2, and symptoms usually begin when the valve area becomes less than 2.5 cm2. Mitral stenosis (MS) nearly always results from previous rheumatic fever. In fact, a history of rheumatic fever can be elicited in up to 60% of patients with MS. A period of 20 to 40 years may transpire between the occurrence of rheumatic fever and the onset of symptoms, and another 10 years may elapse before these symptoms become disabling.10 The ratio of women to men with MS is 2 : 1. MS can also result from severe degenerative calcification, especially in the elderly. Dyspnea is the cardinal symptom of significant MS. Shortness of breath may not develop in patients with milder MS until AF with rapid ventricular response or pregnancy occurs or it is precipitated by exercise or infection.

Percutaneous mitral balloon valvotomy in the hands of skilled operators can be the procedure of choice in patients with moderate to severe MS who are symptomatic (significant MR and left atrial thrombus are contraindications to this procedure).11 Open surgical commissurotomy and mitral valve replacement are other alternatives for mitral valve treatment.

Mitral Regurgitation

Clinically, however, most patients will have chronic MR. The heart will compensate by increasing LV size (the usual mechanism for chronic volume overload). This increased size allows a higher volume at lower pressure. The duration of this asymptomatic chronic phase is about 6 to 10 years.12 Patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy can be treated with beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. AF rate control is also important. In patients with severe MR who are symptomatic, as well as in asymptomatic patients with severe MR and an ejection fraction of 30% to 60%, surgical therapy is indicated and includes mitral valve repair or replacement.

Mitral Valve Prolapse

MVP is defined as billowing of the leaflets into the left atrium with or without associated MR. Current estimates of MVP based on newer diagnostic criteria suggest that less than 2.5% of the population is affected. Familial causes may represent a manifestation of connective tissue disease. Patients with MVP may experience chest pain, anxiety, palpitations, and dyspnea. Physical examination reveals a midsystolic click, frequently in association with a late systolic murmur.13 Patients suspected of having MVP should arrange follow-up with a cardiologist or primary care physician and will probably undergo echocardiography. Patients with MVP who have had a transient ischemic attack or cerebrovascular attack should be treated with daily acetylsalicylic acid.14

Prosthetic Valve Disorders

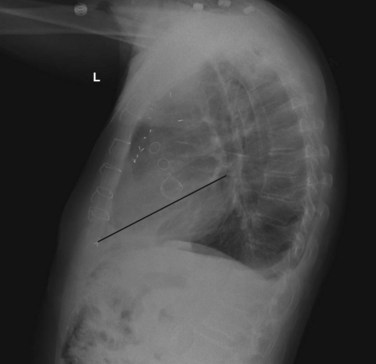

A lateral chest radiograph can help in identifying a prosthetic valve. An imaginary line is drawn from the cardiac apex to the carina. Valves above this line are aortic and pulmonic, whereas valves below this line are mitral and tricuspid (Fig. 61.1).

Disposition

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Intensity (grade 1-6 out of 6), timing during the cardiac cycle, location, and radiation are the principal ways to characterize a cardiac murmur.

Comment on heart size and chamber enlargement on the chest radiograph and whether left ventricular hypertrophy is present on the electrocardiogram.

Document the rationale if transfer is required for urgent cardiology or cardiothoracic surgery consultation.

Document risk-benefit discussions with patients and consultants when reversing anticoagulation in patients with mechanical prosthetic valves.

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Murmurs are the sound that blood makes as it moves through the heart, and most of these sounds are normal and do not represent disease.

An ultrasound of your heart is the way that the doctor determines whether the heart valve is leaking (regurgitation) or whether its opening is narrowed (stenosis).

In most situations, people with heart murmurs and no other symptoms do not need any treatment. Some categories of heart murmurs will require monitoring with ultrasound to evaluate for progression of disease.

Chest pain, fainting, shortness of breath, and palpitations are symptoms that require evaluation by a physician and possible cardiology referral.

1 Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al. 2008 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(13):e1–e142.

2 Braunwald E, Perloff JK. Physical examination of the heart and circulation. In: Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, et al. Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005:77.

3 Maganti K, Rigolin VH, Sarano ME, et al. Valvular heart disease: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010 May;85(5):483–500.

4 Gorlin R, Gorlin SG. Hydraulic formula for calculation of the area of the stenotic mitral valve, other cardiac valves, and central circulatory shunts. Am Heart J. 1951;41:1–29.

5 Pellikka PA, Nishimura RA, Bailey KR, et al. The natural history of adults with asymptomatic, hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:1012–1017.

6 Alborino D, Hoffmann JL, Fournet PC, et al. Value of exercise testing to evaluate the indication for surgery in asymptomatic patients with valvular aortic stenosis. J Heart Valve Dis. 2002;11:204–209.

7 Leon MB, Smith CR. Mack M, et al, for the PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597–1607.

8 Stout KK, Verrier ED. Acute valvular regurgitation. Circulation. 2009;119:3232–3241.

9 Borer JS, Bonow RO. Contemporary approach to aortic and mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 2003;108:2432–2438.

10 Olesen KH. The natural history of 271 patients with mitral stenosis under medical treatment. Br Heart J. 1962;24:349–357.

11 Cubeddu RJ, Palacios IF. Percutaneous techniques for Mitral valve disease. Cardiol Clin. 2010;28:139–153.

12 Rosenhek R, Rader F, Klaar U, et al. Outcome of watchful waiting in asymptomatic severe mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 2006;113:2238–2244.

13 Freed LA, Levy D, Levine RA, et al. Prevalence and clinical outcome of mitral-valve prolapse. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1–7.

14 Sacco RL, Adams R, Albers G, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attacks. A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:577–617.