CHAPTER 67 Cardiac Tumors

BENIGN CARDIAC TUMORS

Myxoma

Definition

Cardiac myxomas are benign neoplasms of endocardial origin, most commonly located in the atria.

Prevalence

With an incidence of 0.03%, cardiac myxoma is the most common primary cardiac tumor.1 It represents approximately 50% of all benign cardiac tumors.2 Myxomas have been reported in patients of every age, but most frequently patients present with myxomas between the third and sixth decades, with an average age of approximately 50 years.2,3 There is a higher prevalence in women.2

A rare autosomal dominant form of cardiac myxoma is termed the Carney complex. Associated features include pigmented skin lesions, cutaneous myxomas, primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease, mammary myxoid fibroadenomas, large cell calcifying Sertoli-cell tumors, pituitary adenomas, thyroid tumors, and melanotic schwannomas.4 Patients with the Carney complex present at an earlier age compared with patients with sporadic cases of cardiac myxoma, with an average age of 26 years.4 These patients are also more predisposed to develop multiple tumors, documented in 41%4 compared with 6% of patients with sporadic cardiac myxomas.5

Pathology

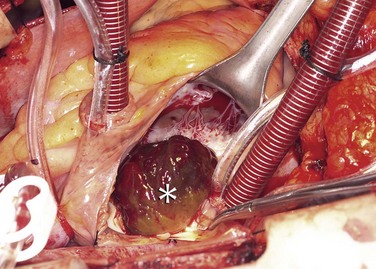

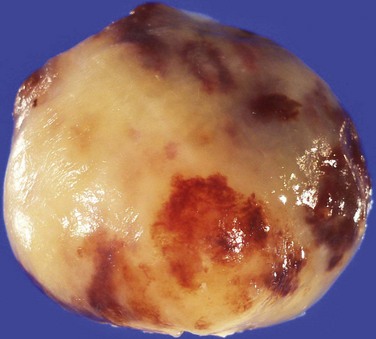

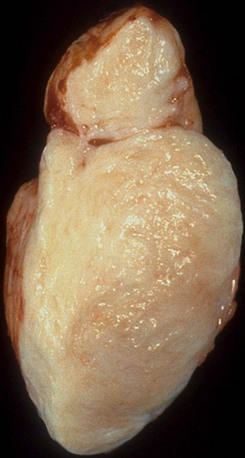

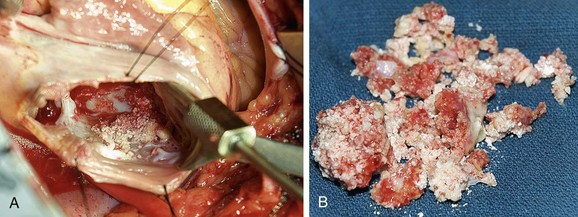

Cardiac myxomas arise from the endothelial surface by either a narrow or a broad-based pedicle and extend into the cardiac chamber (intracavitary growth) (Fig. 67-1). They range in size from 1 to 15 cm in diameter (average 5 to 6 cm).2 Approximately 75% originate in the left atrium, 15% to 20% originate in the right atrium, and 5% are biatrial.1 Myxomas rarely occur within the ventricular chamber or along the atrioventricular valves. Most are smoothly marginated, firm, and fibrotic (Fig. 67-2). The remaining one third to one half are gelatinous and friable with a villous or frondlike surface (Fig. 67-3).1 This latter type is the morphology typically found in the Carney complex and is more likely to produce embolization.6 Focal areas of hemorrhage may be evident on the surface of a myxoma.

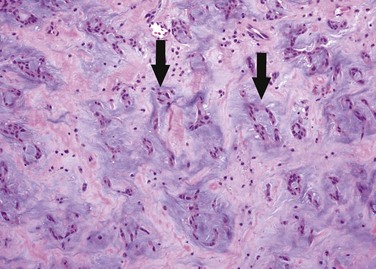

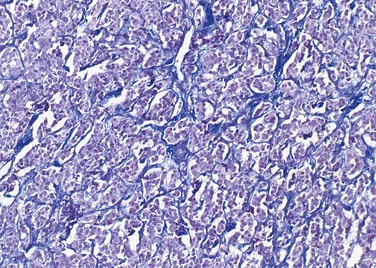

Histologically, myxomas consist of inflammatory cells and myxoma cells in a myxoid matrix (Fig. 67-4). Myxoma cells are stellate multinucleate cells that form elongated cords and rings.6 They are of uncertain origin, but may arise from residual embryonal multipotential mesenchymal cells of the heart.2 Myxomas also characteristically contain cysts, hemorrhage, extramedullary hematopoiesis and, rarely, glandular elements.6 Calcification is common microscopically, and for unknown reasons is more prevalent in lesions on the right side of the heart.1

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Clinical presentation is extremely varied and depends on location, morphology, and size of the myxoma. The classic clinical triad is intracardiac obstruction, embolization, and constitutional symptoms.2 Approximately 20% of patients are asymptomatic.5 The most common symptoms of cardiac myxomas are secondary to obstruction.3 Obstruction from left atrial myxomas mimics mitral valve stenosis, causing dyspnea and orthopnea from pulmonary edema. Obstructive right atrial myxomas may produce peripheral edema and syncope. Ventricular myxomas may mimic aortic or pulmonic valve stenosis, causing syncope. Obstruction may be intermittent and positional with pedunculated tumors.3 Sudden cardiac death is rare, caused by temporary complete obstruction of the mitral or tricuspid valve.2 Additionally, the motion of pedunculated atrial tumors may cause incomplete closure of, or damage to, the atrioventricular valve apparatus.2

Emboli have been reported in 35% of left-sided and 10% of right-sided cardiac myxomas.3 Most emboli are systemic, originating from left-sided lesions or paradoxical emboli originating from right atrial myxomas. They may affect the cerebral, visceral, renal, peripheral, or coronary arteries. Clinically evident pulmonary emboli are infrequent, but have been reported in right-sided cardiac myxomas.2

Constitutional symptoms, including fever, fatigue, and weight loss, occur in approximately one third of patients.3 Other reported symptoms include arthralgias, myalgias, rashes, clubbing, cyanosis, and Raynaud phenomenon.2 Cardiac arrhythmias or palpitations occur in 20% of patients with myxomas.3 Less common presentations include chest pain, anemia, and sepsis.

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Radiography

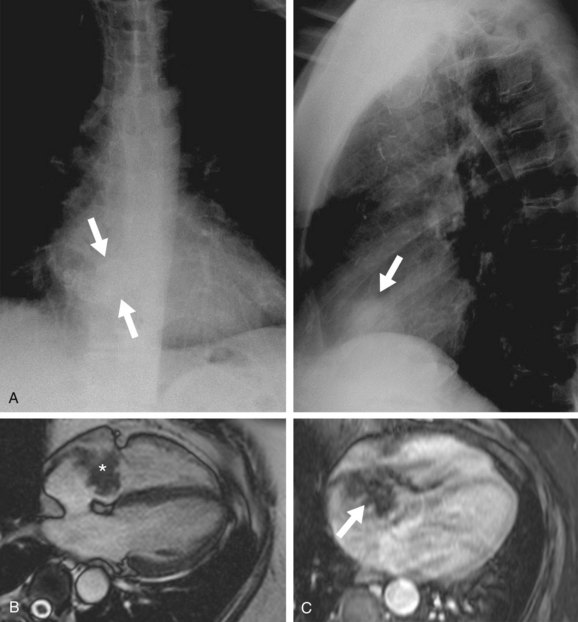

Findings on chest radiograph vary with tumor location. Approximately 50% of left atrial myxomas produce findings suggestive of mitral valve obstruction, such as left atrial enlargement, prominence of the left atrial appendage, vascular redistribution, and pulmonary edema (Fig. 67-5).3 Cardiomegaly and pleural effusions are less frequent findings, but may occur with either right-sided or left-sided myxomas. Radiographically evident calcification is reported in 50% of right atrial myxomas, but is not seen in left atrial myxomas.3 Approximately one third of chest radiographs are normal.3

Ultrasonography

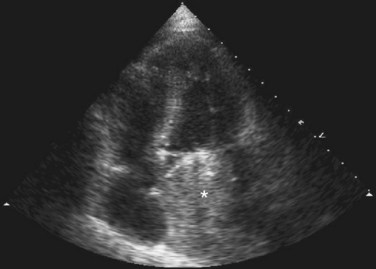

Transesophageal echocardiography may allow for better visualization of atrial tumors compared with the transthoracic approach (Fig. 67-6). Myxomas are pedunculated mobile masses on echocardiography, often apparently attached to the interatrial septum by a narrow stalk.7 Myxomas may be homogeneous or heterogeneous, with echogenic foci owing to calcification and hypoechoic areas from hemorrhage, necrosis, or cysts.7 Dynamic prolapse of the mass across the atrioventricular valve is often well visualized on echocardiography.

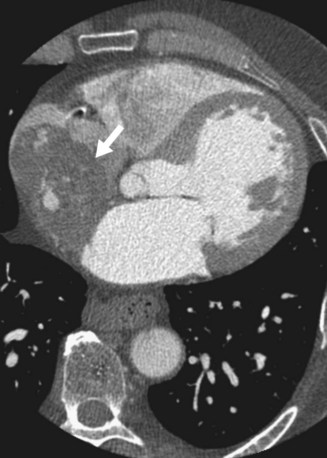

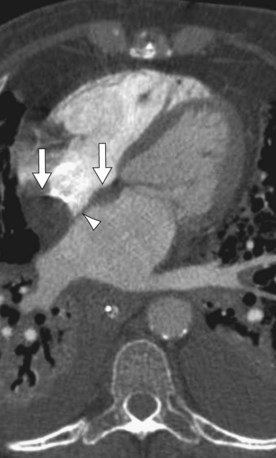

Computed Tomography

On contrast-enhanced CT, cardiac myxomas appear as intracavitary round or ovoid filling defects with smooth or lobulated contours.3 Most myxomas are hypodense to myocardium and unopacified blood (Fig. 67-7).3,5 Myxomas tend to enhance heterogeneously after administration of contrast medium (Fig. 67-8).3 CT may show a narrow base of attachment to the interatrial septum, although a pedicle is usually not as well seen as with echocardiography.7 Calcification may be evident, but typically only in right heart myxomas. Secondary complications of myxomas may be identified on CT, including pulmonary or visceral emboli and evolving infarction.3

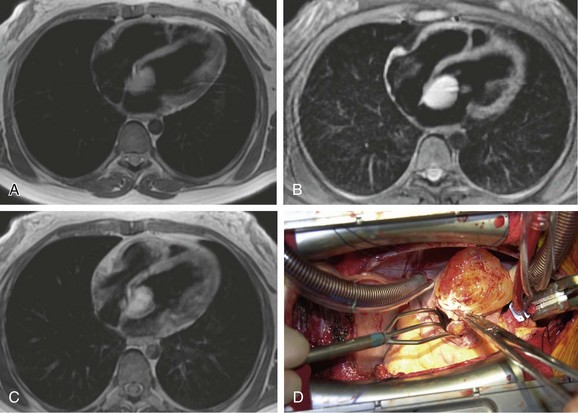

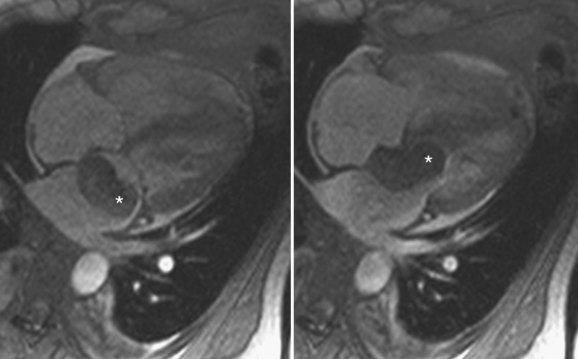

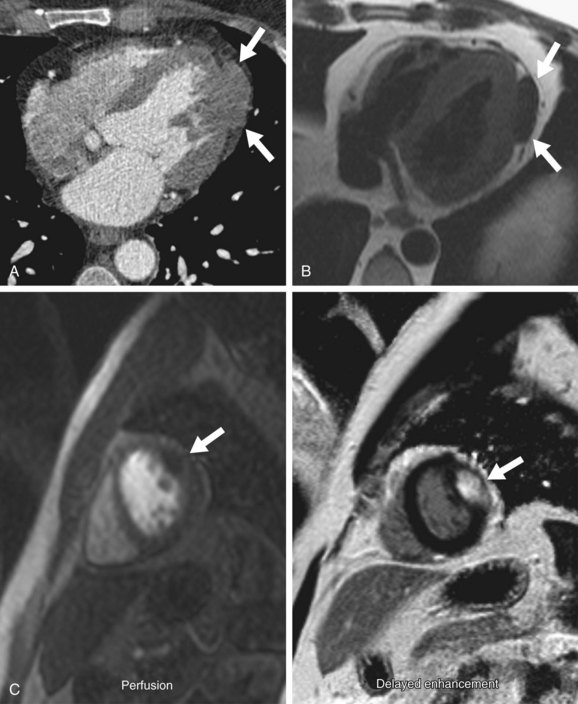

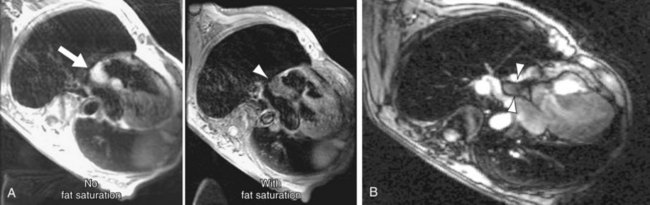

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

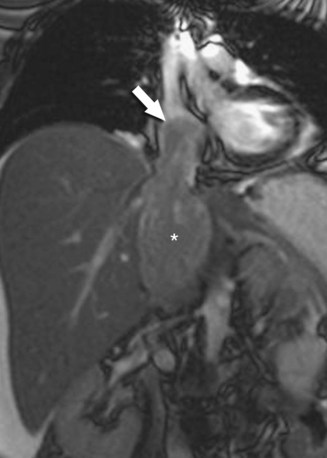

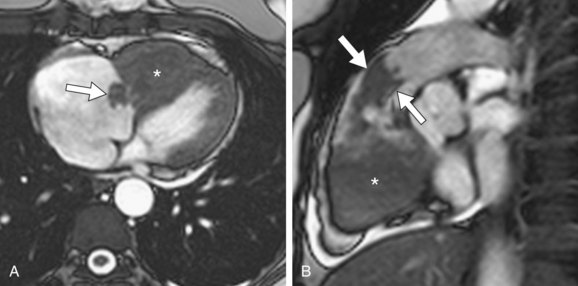

On MRI, myxomas are usually isointense on T1-weighted sequences and high signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences because of their myxoid stroma composition (Fig. 67-9A and B).8 Myxomas are typically heterogeneous, likely reflective of varying components of hemorrhage, calcification, cysts, and myxoid or fibrous tissue.3 Loss of signal intensity occurs with gradient-recalled-echo (GRE) imaging possibly because of magnetic susceptibility from high iron content.3 Myxomas are usually hypointense to blood pool and hyperintense to myocardium on steady-state free precession (SSFP) sequences, although they may be isointense to blood and possibly missed on this sequence.9 Myxomas enhance with gadolinium, usually with a heterogeneous pattern on perfusion and delayed enhancement phases (Fig. 67-9C).10 MRI has been reported to be more accurate than CT in predicting the point of attachment to the wall, which may be best seen on cine images.3 Cine MRI also may show prolapse of the tumor across a cardiac valve (Fig. 67-10).10

Treatment Options

To prevent complications such as embolization or sudden cardiac death owing to valvular obstruction, the treatment of cardiac myxoma is prompt surgical resection. The stalk and zone of attachment are excised, including the full thickness of the interatrial septum for myxomas that arise in this location. Long-term prognosis is excellent. Recurrence occurs in less than 3% of nonfamilial cases and is considered related to incomplete resection.2 In patients with the Carney complex, recurrence is 20%, which may be due in part to multifocality of lesions.2,4

Papillary Fibroelastoma

Prevalence

Cardiac papillary fibroelastomas are the second most common primary cardiac tumor, representing approximately 10% of benign cardiac tumors.7 They are the most common tumor of the cardiac valves. Papillary fibroelastomas have been reported in all ages, but are most frequently found in the fourth to eighth decades of life, with a mean age of 60 years.11 In the largest case analysis, there was a slight male predominance of 55%.11 This lesion is usually solitary, and no familial cases have been described.

Pathology

Papillary fibroelastomas consist of multiple fronds attached to the endocardium by a short pedicle. When immersed in water or saline, they are described as having the appearance of a sea anemone (Fig. 67-11).1 The papillary fronds are avascular with an elastic fiber and collagen core surrounded by myxomatous matrix and endothelial cells.6 Dystrophic calcification has been reported, but is rare.11 Most lesions are approximately 1 cm in maximum diameter, although lesions up to 7 cm in size have been reported.11 More than 75% of papillary fibroelastomas are found on the cardiac valves, involving the aortic, mitral, tricuspid, and pulmonary valves in decreasing frequency.11 Aortic and pulmonary valve papillary fibroelastomas most commonly project into the vascular lumen, whereas papillary fibroelastomas on the atrioventricular valves usually project into the atria.11 They may also occur along the endocardial surfaces of the atria and ventricles or on the eustachian valve.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Most papillary fibroelastomas are found incidentally during imaging, cardiac surgery, or autopsy.11 No longitudinal studies have been performed, and the natural history of these lesions is unknown. The most common clinical manifestation is embolism. Either the tumor itself or associated thrombus may embolize into the cerebral, visceral, renal, peripheral, coronary, or, less frequently, pulmonary arteries.11 Heart failure, arrhythmia, syncope, and sudden death are less common manifestations.

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Radiography

Because of their small size, papillary fibroelastomas would not be expected to produce any findings on chest radiography. If there is obstruction of the mitral valve, findings of pulmonary venous hypertension may be apparent. Calcification is rarely visible.11

Ultrasonography

Most papillary fibroelastomas are found incidentally during echocardiography. They typically appear as small, homogeneous, valvular masses that may be sessile or pedunculated.5 A stippled pattern may be seen near the edges, reflective of the papillary projections.11 Almost half of papillary fibroelastomas are mobile with evidence of flutter or prolapse.11,12

Computed Tomography

The few studies of the CT appearance of papillary fibroelastomas have used ECG gating. They describe a tiny, well-defined spherical mass attached to a valve leaflet (Fig. 67-12).13,14

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Because of their small size, papillary fibroelastomas are infrequently visualized on MRI. Papillary fibroelastoma is typically a mobile, nodular mass with homogeneous intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted sequences and intermediate or low signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences.14,15 It is best appreciated on cine MRI sequences as a small valvular mass with adjacent turbulent blood flow.10 It is characteristically hypointense to myocardium on GRE sequences.16 After administration of gadolinium, papillary fibroelastomas show delayed hyperenhancement possibly because of their fibroelastic tissue composition.13,17

Fibroma

Prevalence

Cardiac fibromas are the second most common tumor in childhood after rhabdomyoma. In contrast to rhabdomyomas, they are uniformly solitary.5 One third of patients present before 1 year of age, although 15% of cardiac fibromas are discovered in adolescence and adulthood.5 There is no sex predilection.18 Fibromas are associated with Gorlin syndrome (also known as basal cell nevus syndrome), an autosomal dominant syndrome of multiple basal cell carcinomas, odontogenic keratocysts, skeletal anomalies, and other neoplasms such as medulloblastoma.8

Pathology

Fibromas are mural-based whorled masses of white tissue (Fig. 67-13). Mean size is 5 cm (range 2 to 10 cm).5,7 They are not encapsulated and may have either circumscribed or infiltrating margins. Fibromas are typically located in the interventricular septum or left ventricular free wall.1,6 Less frequently, they are found in the right ventricle or atria. In newborns and infants, fibromas are highly cellular with numerous fibroblasts. With age, cellularity decreases, and the amount of collagen increases.6,19 Fibromas contain microscopic calcification in one third of cases; they are otherwise fairly homogeneous on histologic and gross examination.6

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Fibromas are asymptomatic in one third to one half of cases. Symptoms include heart failure, arrhythmia, chest pain, syncope, and sudden death.1,20 In one study of primary cardiac tumors that caused sudden cardiac death, fibroma was the second most common underlying cause (after endodermal heterotopia of the atrioventricular node).21

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Radiography

The most common abnormality on chest radiograph is cardiomegaly.22 A focal bulge of the cardiac contour can also be seen.19 Calcification overlying the cardiac silhouette is visualized radiographically in approximately one quarter of cases, and may appear dense or amorphous.5,20

Ultrasonography

Cardiac fibroma may appear as a discrete mass or a focal area of wall thickening mimicking focal hypertrophic cardiomyopathy on echocardiogram. Fibromas are echogenic and may appear heterogeneous.5

Computed Tomography

Fibromas are circumscribed or infiltrative mural-based masses on CT (Fig. 67-14A). They show soft tissue attenuation and often calcification.8 Enhancement may be either homogeneous or heterogeneous.5,19

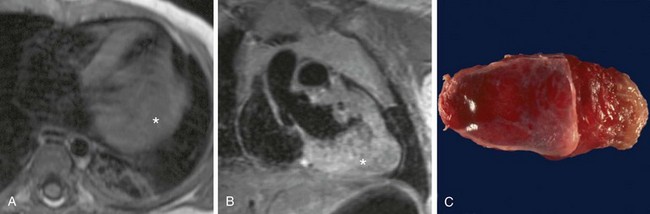

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

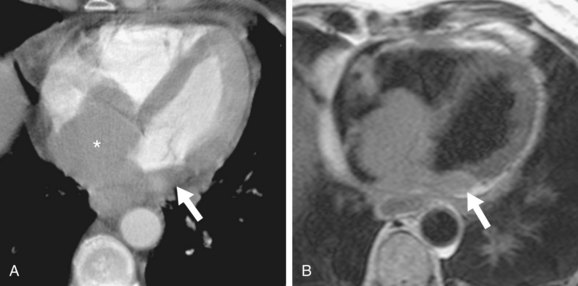

On MRI, a cardiac fibroma appears as an intramural mass or focal myocardial thickening on T1-weighted sequences, where it is isointense or hypointense to myocardium (Fig. 67-14B).8,23 In contrast to other cardiac tumors, fibromas are characteristically hypointense on T2-weighted and SSFP sequences because of their fibrous tissue composition, which has low water content.8,23,24 The fibrous tissue is also hypovascular, causing little or no enhancement on perfusion imaging (Fig. 67-14C).24 On myocardial delayed enhancement MRI, fibromas typically show marked hyperenhancement, however, occasionally with central regions of hypointensity (see Fig. 67-14C).24 The delayed enhancement is currently attributed to the significant extracellular space for gadolinium accumulation.24

Treatment Options

In contrast to soft tissue fibromatosis, there is little evidence that cardiac fibromas may enlarge, and spontaneous regression has been reported.1 Treatment for symptomatic patients is complete surgical excision, although partial excision may be performed for more extensive tumors. Postsurgical recurrence is rare.5

Rhabdomyoma

Prevalence

Rhabdomyoma is the most common cardiac neoplasm in infants and children, and accounts for 50% to 75% of pediatric cardiac tumors.10 It occurs equally in boys and girls.10 Approximately 50% of patients with rhabdomyomas have tuberous sclerosis, an association that increases to 95% in fetuses and neonates with multiple cardiac tumors.25 Conversely, virtually all infants with tuberous sclerosis have cardiac rhabdomyomas, although this incidence decreases with age because of spontaneous regression.8 Rhabdomyoma is rarely associated with congenital heart diseases, such as Ebstein anomaly, tetralogy of Fallot, and hypoplastic left heart syndrome.22

Pathology

Rhabdomyomas usually consist of circumscribed mural-based nodules that average 1 to 3 cm in size; multiple nodules are present in 70% to 90% of cases.1 The left ventricle or interventricular septum is the most common location, followed by the right ventricle and atria in decreasing frequency.26 Rhabdomyomas protrude into the cardiac chambers in 50%,27 a characteristic observed more often in patients who do not have tuberous sclerosis.6 Histologically, the rhabdomyoma cell has a distinctive spider-like appearance with vacuolated cytoplasm and radiating myofibers surrounding a central nucleus. The cells stain with periodic acid–Schiff because of their high glycogen content.5

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Rhabdomyomas are most commonly diagnosed incidentally on routine second-trimester fetal ultrasound examinations.27 The most frequent presentation in utero is arrhythmia, including tachycardias and bradycardias.26 Additional fetal manifestations include hydrops and fetal death. Infants may be asymptomatic or present with arrhythmia, heart failure, or left ventricular outflow obstruction.26

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Computed Tomography

CT scan may show multiple intramural nodules that appear either hypodense or hyperdense to normal myocardium.28

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Cardiac rhabdomyomas are intramural masses that are isointense on T1-weighted MRI sequences and hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences (Fig. 67-15).8 They may produce focal abnormalities of contractility.8 Rhabdomyomas enhance homogeneously and intensely with gadolinium.8,10 Numerous rhabdomyomas less than 1 mm in size, so-called rhabdomyomatosis, may produce diffuse myocardial thickening without a discrete mass.53

Lipoma

Prevalence

Lipomas reportedly represent 8% of primary cardiac tumors,29 although this may be an overestimate because many series do not differentiate lipomas from LHIS. They may manifest at any age, but patients are typically younger than patients with lipomatous hypertrophy.30 There is no gender prevalence.29

Pathology

Lipomas are circumscribed masses of homogeneous yellow fat that may be found within the myocardium, occasionally with extension into the pericardial space or cardiac chambers. The most common sites are the right atrium, left ventricle, and interatrial septum.29 Half are subendocardial, with the remaining half split between myocardial and subepicardial locations.29 Histologically, lipomas are encapsulated masses of mature fat cells, without the brown fat or hypertrophic myocytes found in lipomatous hypertrophy.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Most cardiac lipomas are asymptomatic and are discovered during imaging or autopsy. Occasionally, they may cause obstruction or arrhythmias.8

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Ultrasonography

Lipomas are nonspecific homogeneous, immobile echogenic masses on echocardiography.5

Computed Tomography

CT and MRI have the advantage over echocardiography of being able to characterize the tissue type. Lipomas have homogeneous low attenuation on CT similar to subcutaneous or mediastinal fat, typically less than −50 Hounsfield units (Fig. 67-16). Thin strands of soft tissue attenuation septa may be present without any nodularity. No significant enhancement occurs with administration of contrast medium.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

On MRI, lipomas are homogeneous, smoothly contoured masses. They show homogeneous fat signal intensity on all sequences, including decreased signal intensity on fat-suppressed sequences, and no enhancement with gadolinium.8,29 There may be thin septations, but no nodular components. Chemical shift artifact occurs on SSFP sequences at the interface between the lipoma and the myocardium or blood pool, resulting in a low signal intensity margin.29

Lipomatous Hypertrophy of the Interatrial Septum

Definition

LHIS is not a true neoplasm, but rather a benign diffuse thickening (defined as >2 cm) of the normal extension of epicardial fat within the interatrial groove.30

Prevalence

LHIS is significantly more common than true cardiac lipomas. In a prospective study of sequential chest CT scans, the incidence was 2.2%.31 The reported age range is 22 to 91 years, with most patients presenting with LHIS older than 60 years.30 Associations include age, obesity, pulmonary emphysema, and long-term parenteral nutrition.31 Some reports suggest a slight female predominance.30,31

Pathology

Lipomatous hypertrophy is a misnomer because the lesion actually represents hyperplasia rather than hypertrophy of the normal fat found within the interatrial septum. LHIS is a nonencapsulated, poorly circumscribed thickening of the fat of the interatrial groove that extends from the aortic root caudally to the coronary sinus; it is occasionally contiguous with mediastinal fat. LHIS spares the fossa ovalis, causing a bilobed appearance. In a prospective CT study, the thickness ranged from 2 to 6.2 cm (mean 3.2 cm).31 A combination of vacuolated brown fat cells, hypertrophic myocytes, and normal mature fat cells is seen on histologic examination.6

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Although most often an incidental finding, LHIS can be associated with supraventricular arrhythmias, sudden cardiac death, and heart failure.31

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Ultrasonography

Echocardiography shows an echogenic, dumbbell-shaped mass in the interatrial septum sparing the fossa ovalis.32

Computed Tomography

CT reveals a homogeneous fatty attenuation mass, shaped like an hourglass or a dumbbell, which shows focal sparing at the fossa ovalis (Fig. 67-17). No significant enhancement occurs with administration of contrast medium. A large amount of concomitant epicardial or mediastinal fat, or both, is often present.29,31

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

LHIS also has an hourglass shape on MRI. It is homogeneous and similar in signal intensity to subcutaneous or mediastinal fat on all sequences, with signal dropout on fat saturation sequences (Fig. 67-18A).29 SSFP sequences show central hyperintensity with a low signal intensity margin at the interface with blood or myocardium, presumably from chemical shift artifact (Fig. 67-18B).29

Paraganglioma

Prevalence

Cardiac paragangliomas are extremely rare. Only 1% to 2% of pheochromocytomas or paragangliomas are found within the thorax, most of which are located in the posterior mediastinum. Cardiac paragangliomas typically manifest in adulthood, with an age range of 18 to 85 years (mean 40 years).5 Extracardiac paragangliomas occur in about 5% to 10% of patients with a cardiac paraganglioma.34 Metastatic disease also occurs in 5% to 10% of cases of cardiac paragangliomas, typically involving the skeleton. Cardiac paraganglioma has been described in a patient with the Carney triad, which consists of gastrointestinal stromal tumor, pulmonary chondroma, and extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma.34 To our knowledge, cardiac paragangliomas have not been reported in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes.

Pathology

Cardiac paragangliomas are usually masses 3 to 8 cm in diameter with encapsulated or infiltrative margins and central necrosis.8 They follow the distribution of cardiac paraganglia, most involving the left atrium.34,35 Other reported locations include the interatrial septum, the anterior surface of the heart, the right atrium, the aortic root, and the left ventricle.35 Cardiac paragangliomas have identical histology to extracardiac paragangliomas, with nests of paraganglial cells, described as zellballen, surrounded by sustentacular cells (Fig. 67-19).5,6

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Approximately half of paragangliomas are functional, causing hypertension.6 Additional symptoms of catecholamine excess include flushing, sweating, palpitations, anxiety, paresthesias, headache, and weight loss. Depending on location and size, mass effect may cause obstruction or compression of adjacent mediastinal structures.36 Laboratory abnormalities are similar to those of adrenal pheochromocytoma, with elevated urine or blood catecholamines, metanephrine, or vanillylmandelic acid.

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Radiography

In a small series, the most common finding on chest radiographs was a middle mediastinal mass, most splaying the carina.34

Ultrasonography

Cardiac paragangliomas are echogenic masses most often involving the left atrium.7 Echocardiography may show compression of nearby structures, including the superior vena cava.

Computed Tomography

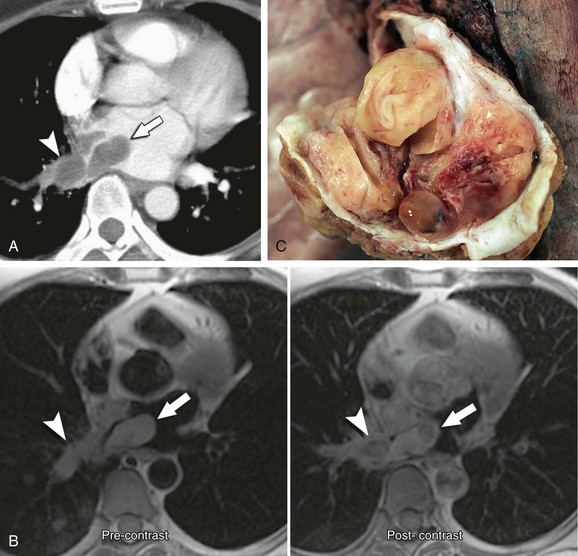

CT reveals a mass typically involving the roof or posterior wall of the left atrium with circumscribed or infiltrative margins.34 Enhancement is usually intense, with about half of cases showing peripheral enhancement with central low attenuation areas compatible with cystic change or necrosis.5

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Cardiac paragangliomas are isointense or hypointense to myocardium on T1-weighted MRI sequences (Fig. 67-20A), although they may contain areas of hyperintensity from hemorrhage. On T2-weighted sequences, they are generally markedly hyperintense and may appear “light-bulb bright” (Fig. 67-20B), similar to their adrenal counterpart.8 Paragangliomas often show intense, heterogeneous enhancement with central nonenhancing components attributable to foci of necrosis (Fig. 67-20C).8

Calcified Amorphous Tumor of the Heart

Definition

Calcified amorphous tumor is a rare, non-neoplastic, diffusely calcified mass of uncertain etiology.

Prevalence

Prevalence of calcified amorphous tumor is extremely low, with very few case reports in the literature. In the largest series of 11 cases, the age range at presentation was 16 to 75 years (mean 52 years).37

Pathology

Most cases of calcified amorphous tumor are pedunculated intracavitary masses, although it has also been reported to involve diffusely the myocardium, papillary muscles, and valve chordae.37,38 The tissue is grossly a yellow-white color (Fig. 67-21). Microscopic analysis shows nodular deposits of calcium within a background of amorphous fibrinous material.37 One hypothesis for the origin of calcified amorphous tumor is degeneration and organization of intramural thrombus; however, hemosiderin and laminations, usually found in organizing thrombi, are rare within this lesion.37

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of calcified amorphous tumor includes heart failure, syncope, and evidence of embolization.37

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Radiography

Chest radiograph may show dense calcification within the cardiac silhouette (Fig. 67-22A).38

Ultrasonography

Most lesions evaluated with echocardiography were pedunculated, intracavitary diffusely calcified masses.37

Computed Tomography

There is little literature regarding cross-sectional imaging of calcified amorphous tumor of the heart. Two studies that include CT findings describe a pedunculated, calcified right ventricular mass in one case,39 and diffuse dense calcification of the left ventricle apical, septal, and lateral walls; papillary muscles; and mitral chordal apparatus in the other.38

MALIGNANT CARDIAC TUMORS

Metastases

Definition

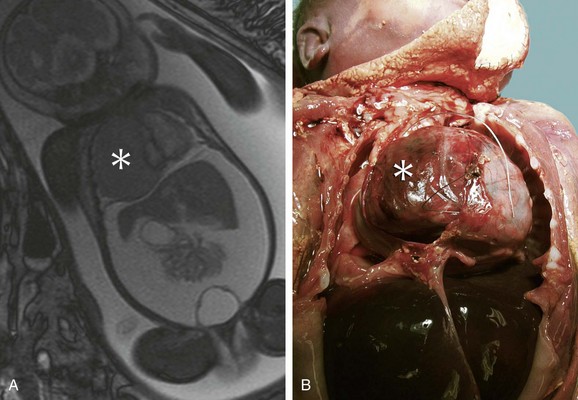

Cardiac metastases are malignancies that involve the myocardium, endocardium, epicardium, or pericardium secondarily. The pathways of spread include direct extension from a mediastinal or thoracic tumor, hematogenous spread, lymphatic spread, and intracavitary extension via the inferior vena cava or pulmonary veins (Figs. 67-23 through 67-26). Lung carcinoma, breast carcinoma, mesothelioma, and other thoracic malignancies may directly invade the heart and pericardium by contiguous growth. Melanoma, sarcomas, leukemia, and renal cell carcinoma tend to deposit neoplastic cells hematogenously within the myocardium. Epithelial malignancies, such as lung or breast carcinoma, tend to metastasize to the heart via lymphatic channels; regional lymphadenopathy and pericardial involvement often accompany superficial myocardial infiltration in these cases. Endovascular spread to the right heart via systemic venous drainage is characteristic of melanoma and renal, adrenal, hepatic, and uterine tumors. Lung neoplasms may invade the left atrium via a pulmonary vein. Lymphomas and leukemias secondarily involve the heart via any of the above-described pathways, typically affecting pericardium, epicardium, and myocardium diffusely.1

Prevalence

Cardiac metastases are far more common than primary cardiac tumors. The incidence of cardiac metastases, largely based on autopsy studies, is 2% to 18% (vs. postmortem rates of primary cardiac tumors, which range from 0.001% to 0.28%).41 The following tumors have a particularly high rate (>15%) of cardiac metastases: leukemia, melanoma, thyroid carcinoma, extracardiac sarcomas, lymphomas, renal cell carcinomas, lung carcinomas, and breast carcinomas. In order of decreasing incidence, the most common malignancies to produce secondary cardiac involvement are lung carcinomas, lymphomas, breast carcinomas, leukemia, gastric carcinomas, melanoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and colon carcinoma.1 According to one large review, the male and female incidences of cardiac metastases are equivalent.41

Melanoma produces the largest tumor burden of any metastatic malignancy in the heart, and the myocardium is involved in almost all cases.1 In one autopsy series, 64% of melanoma cases metastasized to the heart.42 Cardiac metastases in melanoma are also typically accompanied by metastases to several other sites.42

Lymphomas typically show secondary involvement of the heart and pericardium later in the disease course, with median onset 20 months after diagnosis. One autopsy series revealed cardiac involvement in 16% of disseminated Hodgkin and 18% of disseminated non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients.42

Pericardial metastases are overall the most common manifestation of cardiac metastatic disease.41,42 Myocardial metastases are less common and develop in the right heart in 20% to 30% of cases, the left heart 10% to 33% of cases, and both sides in 30% to 35% of cases. Endocardial or intracavitary metastases are unusual (5%), and the valves are almost always spared.1,41 More recent analysis suggests that invasion via the heart’s lymphatic networks represents the major route of cardiac metastases, most often originating from involved mediastinal lymph nodes.41

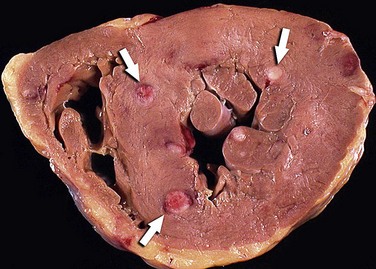

Pathology

On gross inspection, metastatic deposits in the heart vary in appearance and may be multinodular, diffusely infiltrative, or, less likely, a single mass. Tumor deposits may be evident on the pericardial surface. Mediastinal nodal enlargement is reported in 80% of cases. On histologic examination, metastatic foci in the heart tend to show features that identify the primary extracardiac malignancy. Sarcomatous deposits from an extracardiac tumor may be difficult to discern, however, from a primary cardiac sarcoma with intracardiac spread of disease. Extracardiac sarcomas that metastasize to the heart include osteosarcoma, liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, neurofibrosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, and MFH. In some instances, immunohistochemical markers may help to make the distinction between an extracardiac sarcoma and a primary cardiac sarcoma.1

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Cardiac metastases are often clinically undetected and discovered postmortem.41 Depending on their location, however, metastatic deposits in the heart may produce valvular or ventricular outflow obstruction, interruption of conduction pathways, decreased myocardial contractility, coronary artery invasion, or malignant pericardial disease.1 Clinically, patients may experience a range of signs and symptoms, including syncope or right-sided heart failure, dysrhythmias, complete atrioventricular block, diastolic dysfunction with congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, or pericardial effusion.1,41 ECG abnormalities are common.41 Impaired cardiac function reportedly occurs in 30% of patients, most often attributable to a significant pericardial effusion.42 The typical clinical scenario is pericardial tamponade from neoplastic effusion, producing symptoms including chest pain, dyspnea, hypotension, and tachycardia.41 Contiguous endovascular invasion of the right atrium via the inferior vena cava (e.g., metastatic hepatocellular, renal, adrenal, and uterine carcinomas) may produce obstructive pathophysiology, including peripheral edema, tumor emboli, cor pulmonale, and pulmonary arterial hypertension.1,41,43,44

Imaging Techniques and Findings

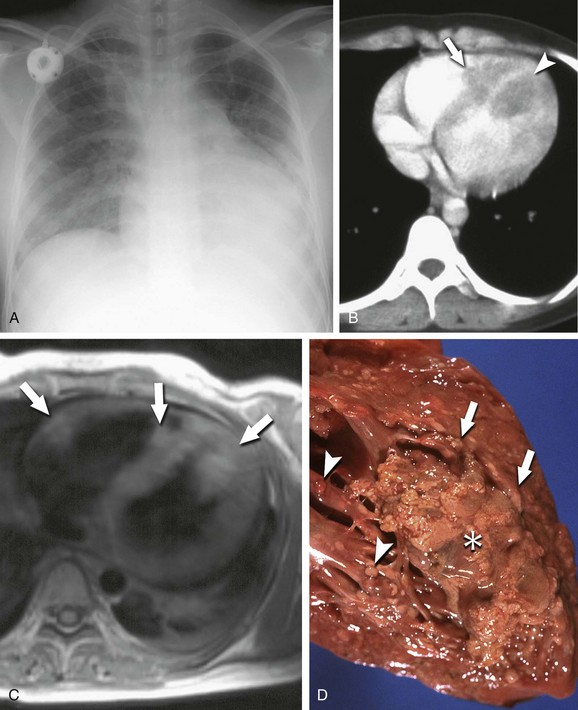

Radiography

The chest radiograph is often unremarkable in cardiac metastatic disease. It may show global enlargement of the cardiac silhouette, however, if a large pericardial effusion is present (Fig. 67-27A). Pulmonary or mediastinal neoplasm, lymphadenopathy, or underlying metastatic disease in the lungs may be evident radiographically in some cases.

Ultrasonography

Transthoracic echocardiography in cardiac metastatic disease may show pericardial effusion or intracavitary, nonmobile and nonpedunculated masses, or both. Cardiac geometry and function may be assessed with parameters of possible obstruction, chamber dilation, compromised valve movement, hypokinesis, and elevated pressure gradients at ventricular outflow tracts.45,46

Computed Tomography

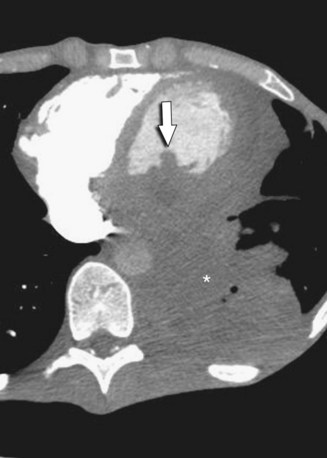

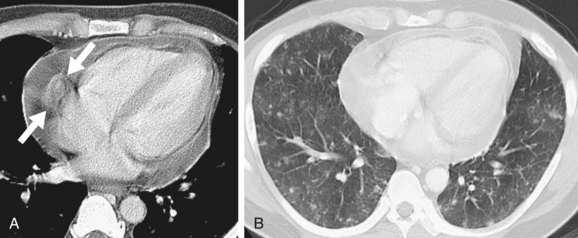

CT provides a more detailed picture of intrathoracic anatomy, potentially revealing a lung carcinoma, pleural-based tumor (e.g., mesothelioma), or mediastinal mass (e.g., lymphoma) with contiguous cardiac invasion. CT may also identify a primary neoplasm or underlying metastatic disease, or both, elsewhere in the chest or upper abdomen. Intramural metastatic tumor deposits in the heart may be evident as myocardial-based nodules or masses (Fig. 67-27B). CT may show aggressive features, including multichamber involvement, intracavitary or intravascular tumor extension, engulfment of the cardiac valves, and pericardial infiltration (Fig. 67-28).42,47 A moderate or large pericardial effusion may be evident and, in advanced cases, accompanied by pericardial thickening or nodularity (Fig. 67-29).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI allows for the differentiation between tumor, cardiac anatomy (myocardium), thrombus, and blood flow artifact. Most cardiac neoplasms are of low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and are brighter on T2-weighted images; they also tend to enhance after intravenous contrast medium administration.42 In the case of metastatic melanoma, intramural nodular deposits characteristically appear bright on T1-weighted and T2-weighted MR images because of the presence of paramagnetic metals bound by melanin (see Fig. 67-27C and D).42 Cine MRI may be helpful to confirm the presence of intravascular or valvular tumor extension (Fig. 67-30). Gadolinium-enhanced MR images may help to distinguish intracavitary tumor from thrombus; enhancement and neovascularity are characteristic of most neoplasms, but not typical of thrombus.42 Changes in cardiac function, including compromised cardiac wall motion and myocardial viability, may also be viewed on MRI.48 It may be difficult to discern benign from malignant cardiac masses based on either CT or MRI; it may not be obvious that the lesion is a metastatic versus a primary cardiac neoplasm unless other evidence exists to suggest the diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Significant pericardial effusion in a patient with underlying malignancy may represent not only advanced neoplastic disease, but also concomitant infectious, drug-induced, radiation-induced, or idiopathic pericarditis.42 An intracardiac mass with multiple myocardial components may represent metastasis, but the differential diagnosis includes unusual primary cardiac neoplasms such as leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma (in children and young adults), rhabdomyoma (in infants), and PCL (in immunosuppressed patients).

Treatment Options

Metastatic tumors in the heart are surgically resected for palliation rather than cure. The clinical goal is at least temporary improvement of cardiac function. Long-term prognosis is poor.1

Angiosarcoma

Definition

Cardiac sarcomas arise from pleuropotential mesenchymal cells within the cardiac muscle.1 In contrast to most other histologic subtypes of cardiac sarcomas (which typically arise in the left atrium), angiosarcomas are located in the right atrium in greater than 90% of cases. Angiosarcomas often infiltrate the pericardium, leading to malignant pericardial effusion.

Prevalence

Primary cardiac sarcomas as a group are rare (<25% of primary cardiac tumors). Angiosarcomas are the most common differentiated histologic subtype (37% of cardiac sarcomas), but the unclassifiable cardiac sarcomas seem to occur with equal frequency.1,49 Mean age at presentation is approximately 40 years (range 3 months to 80 years) with a male predilection (2.5 : 1).21

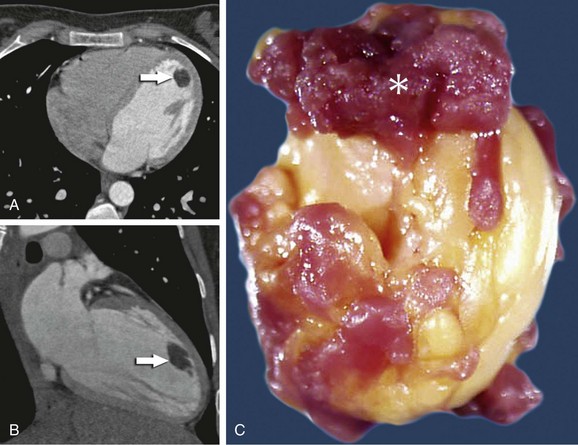

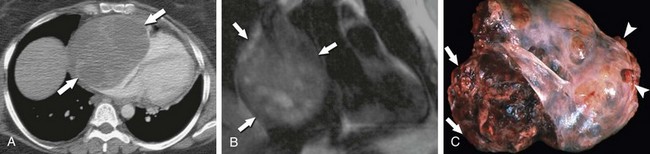

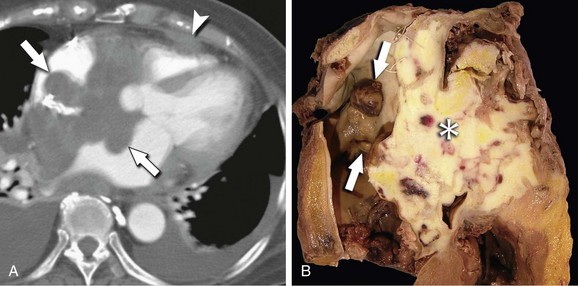

Pathology

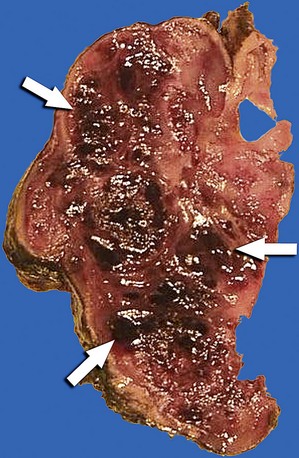

On gross inspection, angiosarcomas are multinodular, hemorrhagic masses centered in the right atrial wall, often with sheetlike pericardial invasion and thickening (Fig. 67-31). There may be contiguous involvement of the venae cavae and tricuspid valve. Histologic features include anastomosing vascular channels lined by malignant endothelial cells that may occasionally form atypical papillary tufts. Vacuoles containing red blood cells may be seen, and most lesions contain areas of necrosis.1,21 Findings of high mitotic rate and necrosis are important predictors of poor patient survival.1

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Clinical presentation is often the consequence of a malignant, often hemorrhagic pericardial effusion producing pericardial tamponade, pericardial restriction, or right ventricular outflow obstruction.21 Signs and symptoms include chest pain, dyspnea, syncope, fever, and lower extremity swelling.1 If the tumor causes valvular obstruction or conduction disturbance, cardiac arrest may result. Cardiac rupture owing to loss of myocardial integrity has been reported. Right-sided cardiac tumors such as angiosarcoma may also produce pulmonary emboli.49

Metastatic disease at clinical presentation is found more often in angiosarcoma than in other cardiac sarcomas; 66% to 89% of patients have metastases within the lung (most commonly), bone, liver, adrenal glands, or spleen.21 Survival is poor for all cardiac sarcomas, regardless of histologic subtype.1 Mean survival for angiosarcoma is 3 months to 2 years after diagnosis.21 Death is frequently due to complications of local recurrence or metastatic disease.

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Radiography

At diagnosis, approximately 30% of patients with cardiac angiosarcoma have pulmonary nodules on the initial chest radiograph compatible with metastases.1 Enlargement of the cardiac silhouette may reflect an underlying malignant pericardial effusion.

Ultrasonography

Echocardiography may reveal a broad-based, chiefly intramural right atrial mass located near the inferior vena cava. Pericardial effusion or contiguous tumor extension into the pericardium, endocardium, and left atrial chamber may be identified.27

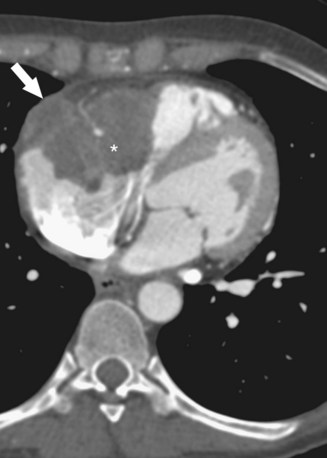

Computed Tomography

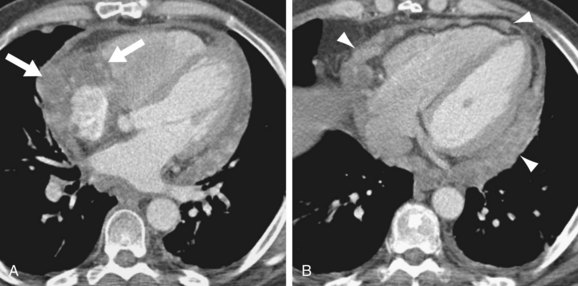

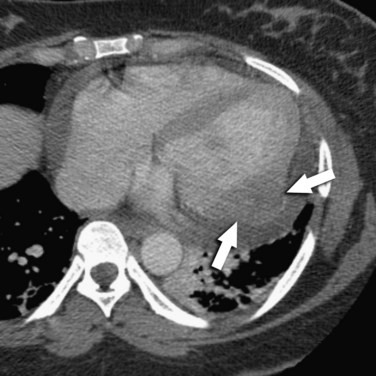

CT often shows a fairly well-defined, enhancing right atrial mass. In many cases, associated pericardial thickening, nodularity, and effusion are present (Fig. 67-32).49 Pulmonary metastases may be evident, occasionally framed by halos of ground glass because of their hemorrhagic character (Fig. 67-33).

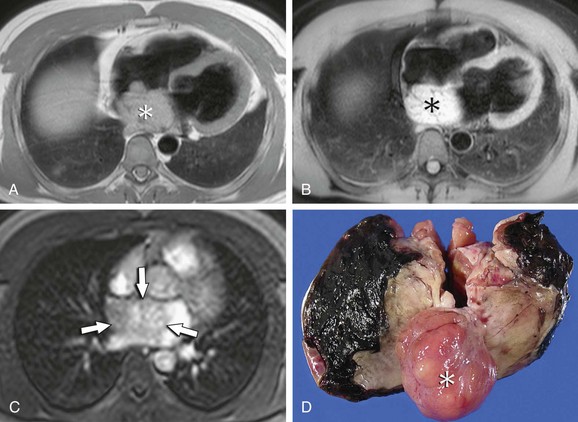

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Angiosarcomas are typically infiltrative masses in the right atrial myocardium that when compared with myocardium are isointense with higher signal intensity areas (owing to focal hemorrhage) on T1-weighted MRI, isointense on T2-weighted sequences, and heterogeneous with areas of high intensity on cine MRI (Fig. 67-34). These tumors tend to show strong, heterogeneous enhancement after contrast administration; this is termed a “sunray” appearance if pericardial tumor infiltration also enhances.8,10

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a right atrial mass includes thrombus, metastatic disease, liposarcoma, angiosarcoma, an unusual right-sided cardiac myxoma or fibroma (both tend to calcify), and PCL.50 Aggressive features, such as a broad-based or intramural tumor configuration, infiltration of the pericardium, involvement of cardiac valves, and pulmonary metastases, all argue in favor of a malignant rather than a benign etiology. The presence of a hemorrhagic pericardial effusion is particularly supportive evidence of angiosarcoma.

Treatment Options

Surgery for cardiac sarcomas may be performed, but depends on tumor location, degree of local invasion, and presence of metastases at presentation. Surgical intervention ranges from open biopsy to palliative debulking to wide surgical resection.49 Cardiac transplantation may be considered if the lesion is considered unresectable, excluding the presence of extracardiac metastases.51 Transplantation is not commonly done because of the high risk of local recurrence and immunosuppression-induced lymphoma (2% to 13% in cardiac allograft recipients).49 Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy may provide limited benefit and may be used in patients with advanced (nonsurgical) disease, local tumor recurrence, or resections with positive tumor margins.49,51

KEY POINTS: ANGIOSARCOMA

Cardiac angiosarcoma must be suspected in the setting of a right atrial mass with pericardial effusion, especially if the pericardial effusion is high attenuation (hemopericardium).

Cardiac angiosarcoma must be suspected in the setting of a right atrial mass with pericardial effusion, especially if the pericardial effusion is high attenuation (hemopericardium).Leiomyosarcoma

Definition

Leiomyosarcomas account for 8% to 10% of cardiac sarcomas and are chiefly located in the posterior wall of the left atrium. Some tumors may represent the atrial extension of sarcomas arising within the pulmonary veins or venae cavae.1,49 In 30% of cases, leiomyosarcomas are multifocal.8

Prevalence

Approximately 75% to 80% of cardiac leiomyosarcomas arise in the left atrium.1 The male-to-female ratio is variably reported (4 : 2 vs. 5 : 7), and sexual predilection cannot be stated with certainty.1 The mean age at presentation has been reported to be 37 years (range 20 to 61 years).1

Pathology

Histologic features of cardiac leiomyosarcoma include intracytoplasmic glycogen, perinuclear vacuoles, blunt-end nuclei, fascicular growth at right angles, and cytoplasmic fuchsinophilia. The distinction between leiomyosarcoma and MFH at microscopic inspection may be difficult.1

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

As an aggressive left atrial mass, leiomyosarcomas may produce clinical signs and symptoms of compromised pulmonary venous drainage (including pulmonary edema) or mitral valve obstruction or both.8,10 Prognosis is poor. Mean survival after diagnosis is 7 to 9 months.1 Patients with the unusual form of right-sided cardiac leiomyosarcoma may have Budd-Chiari syndrome.6

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Radiography

Although no specific reports are available concerning radiographic manifestations of leiomyosarcoma, the most common radiographic abnormality in cardiac sarcomas overall is cardiomegaly.5 In situations of significantly compromised pulmonary venous drainage resulting from an enlarging left atrial mass, features of prominent septal lines and vascular congestion may develop on chest radiographs.

Computed Tomography

Similar to primary cardiac osteosarcomas, these tumors typically arise in the left atrium as lobulated, low-density lesions that mimic atrial myxoma. Helpful differentiating features of osteosarcoma from myxoma include a broad base of attachment and signs of aggressive behavior including involvement of regional veins, pericardium, and mitral valve.8,49

Treatment Options

Surgical excision of the neoplasm may be attempted, ranging from debulking to attempted wide resection. Cardiac transplantation may be considered in advanced disease except when distal metastases are present.51 Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy may provide some benefit and is indicated in patients with advanced (nonsurgical) disease, local tumor recurrence, or resections with positive tumor margins.49,51

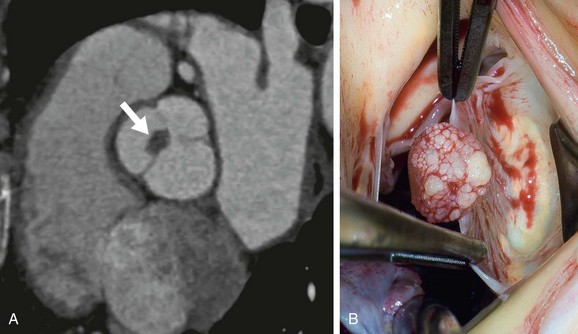

Osteosarcoma

Definition

Cardiac sarcomas with osteosarcomatous differentiation arise almost exclusively (>95%) in the left atrium.1,10 Osteosarcomas commonly involve the mitral valve.8

Pathology

Grossly, cardiac osteosarcomas are typically large tumors (4 to 10 cm) almost uniformly located within the posterior left atrial wall.10 On cut section, they have a pale mucoid or gelatinous appearance with gritty components.6 Microscopic features include osteoid material and atypical osteocytes indistinguishable from skeletal osteosarcomas. Notably, these tumors are often pleomorphic and may contain areas of fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, or giant cell tumor.6

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Clinical presentation includes symptoms of dyspnea, congestive heart failure, mitral valve obstruction, pulmonary hypertension, and syncope.6 Metastatic disease has been reported in lymph nodes, thyroid, skin, lung, and thoracotomy incisions.6 Prognosis is poor.8

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Radiography

No reports are available concerning specific radiographic manifestations of osteosarcoma, but the most common radiographic abnormality in cardiac sarcomas overall is cardiomegaly.5 In situations of significantly compromised pulmonary venous drainage, features of prominent septal lines and vascular congestion may develop on chest radiographs.

Ultrasonography

No reports are available concerning echocardiographic depiction of a cardiac osteosarcoma.

Computed Tomography

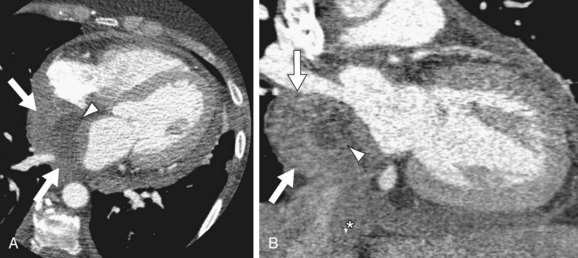

Calcification may be evident on CT images, but this is not a consistent feature of cardiac osteosarcoma.8 This neoplasm mimics a left atrial myxoma, but discerning features include invasion of adjacent structures, a broad base of attachment to the atrial wall, and lack of association with the fossa ovalis (Fig. 67-35A).8

Treatment Options

Excision of the neoplasm should be attempted, ranging from palliative debulking to wide surgical resection. Cardiac transplantation may be considered, but is not indicated when distal metastases are present.51 Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy may provide some benefit and is indicated in patients with advanced (nonsurgical) disease, local tumor recurrence, or resections with positive tumor margins.49,51

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Definition

Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common subtype of cardiac sarcoma in children and young adults.1,8 In contrast to other cardiac sarcomas, rhabdomyosarcoma shows no chamber predilection and does not tend to involve the pericardium.1,27 This tumor is multifocal in 60% of patients, and is more likely than other sarcomas to involve a cardiac valve.8,52

Prevalence

Rhabdomyosarcomas account for 4% to 7% of cardiac sarcomas. Mean age at presentation ranges from 14 to 30 years, which is decades younger than other sarcomas. Sexual predilection (male-to-female) is contradicted in separate case series (2 : 4 or 3 : 2) and is inconclusive.1

Pathology

On gross examination, these tumors are located within the myocardium and tend to exhibit necrotic areas.8 Cardiac rhabdomyosarcomas are embryonal; the diagnostic feature on histologic examination is the presence of rhabdomyoblasts, best identified by periodic acid–Schiff positivity.6 Immunohistochemical staining to identify cells with muscle antigens (desmin and myoglobin) is necessary for diagnosis.1

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Clinical presentation varies because the tumor may arise in any part of the heart, extend into the nearest chamber, and ultimately cause valvular obstruction.22 Infants present with cyanosis, heart murmur, dysrhythmias, or congestive heart failure.22 Older children and young adults present with nonspecific symptoms of fever, weight loss, and malaise.27 Prognosis is poor, and survival is often less than 5 months from diagnosis.1

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Radiography

There are no specific manifestations of rhabdomyosarcoma described on chest radiography. Cardiomegaly is the most common radiographic feature of cardiac sarcomas.5 In situations of significantly compromised pulmonary venous drainage owing to tumor mass effect, features of prominent septal lines and vascular congestion may develop on chest radiographs.

Ultrasonography

Transesophageal or transthoracic echocardiography may reveal intramural involvement by rhabdomyosarcoma (solitary or multifocal), intracavitary extension, and the impact on an adjacent cardiac valve.53

Computed Tomography

On CT, rhabdomyosarcomas are shown as solitary or multifocal intramural masses, often lower in density than normal myocardium.49

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Rhabdomyosarcomas are reported as isointense to myocardium on T1-weighted MRI, isointense or heterogeneous on T2-weighted sequences, and isointense on cine MRI (Fig. 67-36). These tumors tend to enhance heterogeneously after contrast medium administration, with focal nonenhancement in necrotic areas.8,49

Treatment Options

Excision of the neoplasm may be attempted, ranging from palliative debulking to wide surgical resection. In most patients, the tumor is advanced at presentation.52 Cardiac transplantation may be considered, but is excluded when distal metastases are present.51 This malignancy shows poor response to adjuvant radiation or chemotherapy.52

Liposarcoma

Definition

Liposarcoma is a rare histologic subtype of cardiac sarcoma and tends to arise in the right side of the heart.49

Prevalence

Primary cardiac liposarcomas account for less than 1% of cardiac sarcomas. A liposarcoma metastatic to the heart occurs much more frequently than primary cardiac liposarcoma.30

Pathology

Grossly, the tumor has a yellow, soft, and smooth surface with ill-defined margins often bulging into the right atrial or ventricular chamber.30 Histologic features include atypical fat cells with malignant lipoblasts invading the adjacent myocardium.1,30 On microscopic examination, liposarcomas may be easily confused with LHIS and pleomorphic MFH.1

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Similar to other right-sided cardiac masses, liposarcoma may produce the signs and symptoms of valvular dysfunction, right ventricular outflow obstruction, pulmonary embolism, or dysrhythmias.54

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Ultrasonography

Echocardiography may show an echo-free space compatible with a fat-containing tissue mass, with or without intracavitary extension.54

Computed Tomography

Foci of fat density may be evident on CT images (Fig. 67-37), but liposarcomas are also described as soft tissue masses without fat components.8 Areas of low-density necrosis or hemorrhage may be present within the tumor. CT may delineate myocardial, intracavitary, intravascular, or pericardial extension of tumor, and involvement of a cardiac valve (see Fig. 67-37).54 Metastases to the lungs, bone, or brain may also be identified.30

Differential Diagnosis

Treatment Options

Excision of the neoplasm may be attempted, ranging from palliative debulking to wide surgical resection. Cardiac transplantation may be considered, but is not indicated when distal metastases are present.51 Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy may provide some benefit, and is indicated in patients with advanced (nonsurgical) disease, local tumor recurrence, or resections with positive tumor margins.49,51

Primary Cardiac Lymphoma

Definition

PCL is defined as an aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma involving exclusively the heart or pericardium or both, or a non-Hodgkin lymphoma with most of the tumor located within the heart.49 PCL tends to develop in immunocompromised patients.49

Prevalence

PCL is rare, with an incidence of 0.056% in one large autopsy series.55 PCL represents 1.3% of primary cardiac tumors and 0.5% of extranodal lymphomas.55 Approximately 50% of reported cases are in immunocompromised patients, including patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or allograft transplant.1 There is a slight male predominance.10

Pathology

On gross examination, PCL appears as multiple firm, whitish nodular lesions centered in the myocardium or epicardium, often with pericardial infiltration. The right atrium and ventricle are both involved in 75% of cases.10 PCL is less likely than a cardiac sarcoma to show necrotic zones, or valvular or intracavitary invasion.1,8 Virtually all PCLs are high-grade B cell lymphomas.1,6 Immunohistochemical staining is typically positive for common leukocyte and L26 antigens (specific for B cell lymphoma).49 Most PCLs in immunocompromised patients contain Epstein-Barr virus DNA.1,6 Cytology of the pericardial fluid is diagnostic for PCL in 67% of cases.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

In immunocompetent patients presenting with PCL, the average age at presentation is 58 years (range 13 to 80 years).6,10 The most common clinical presentation is congestive heart failure; additional signs and symptoms include dyspnea, dysrhythmias, complete heart block, chest pain, superior vena cava syndrome, or cardiac tamponade owing to a large pericardial effusion.49

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Radiography

Cardiomegaly and signs of pulmonary edema may be evident when a pericardial effusion is present (Fig. 67-38).5,56

Ultrasonography

Echocardiography may reveal hypoechoic masses of the right atrium and ventricle, pericardial effusion, and, occasionally, diastolic collapse of the right heart chambers when cardiac tamponade is present.5,56

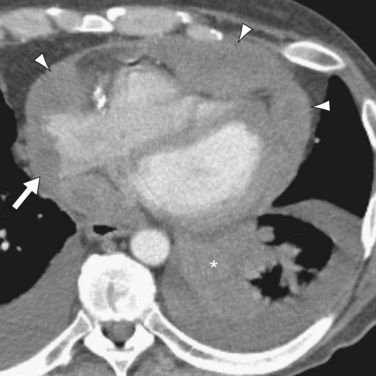

Computed Tomography

PCLs are multinodular, intramural masses located in the right atrium and ventricle, characteristically with pericardial thickening, nodularity, or effusion (Figs. 67-39 and 67-40).10,49 The pericardial effusion may be quite large.10

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

PCLs manifest as nodular or infiltrative lesions that are isointense or hypointense on T1-weighted MRI and hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences (Fig. 67-41). Postcontrast images may show homogeneous or heterogeneous tumor enhancement.8,49 Delayed enhancement imaging (with inversion times to null myocardium) may improve delineation of the tumor.10

Treatment Options

When superior vena caval obstruction develops because of tumor bulk, it may be treated surgically or with metallic stents. In contrast to other cardiac malignancies, gross resection is not indicated in most cases of PCL.49 Randomized trials have shown prolonged survival and reduction of cardiac symptoms with the use of chemotherapy (including anthracycline-based agents), either alone or followed by field radiation.55

SUMMARY

Although there are exceptions, one must also recognize the potentially distinguishing imaging features of benign versus malignant cardiac tumor. Findings suggestive of benignancy include left-sided location, well-defined lesion margins, pedunculated mural attachment (when intracavitary), and lack of associated pericardial effusion or thickening. Features suspicious for malignancy are right-sided heart location; ill-defined tumor margins; wide-based mural attachment (when intracavitary); heterogeneity (necrosis); and, most importantly, the invasion of regional structures including valves, pericardium, regional vessels, or mediastinum. Multifocal intracardiac lesions and pulmonary metastases also suggest an underlying malignant etiology. A simplified approach to the differential diagnosis of cardiac tumors is provided in Table 67-1 with helpful differentiating features listed in parentheses.

Araoz PA, Mulvagh SL, Tazelaar HD, et al. CT and MR imaging of benign primary cardiac neoplasms with echocardiographic correlation. RadioGraphics. 2000;20:1303-1319.

Grebenc ML, Rosado de Christenson ML, Burke AP, et al. Primary cardiac and pericardial neoplasms: radiologic-pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics. 2000;20:1073-1103.

Grebenc ML, Rosado de Christenson ML, Green CE, et al. Cardiac myxoma: imaging features in 83 patients. RadioGraphics. 2002;22:673-689.

Grizzard JD, Ang GB. Magnetic resonance imaging of pericardial disease and cardiac masses. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2007;15:579-607.

Sparrow PJ, Kurian JB, Jones TR, et al. MR imaging of cardiac tumors. RadioGraphics. 2005;25:1255-1276.

Syed IS, Feng D, Harris SR, et al. MR imaging of cardiac masses. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2008;16:137-164.

Uzun O, Wilson DG, Vujanic GM, et al. Cardiac tumours in children. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:11.

Virmani R, Burke A, Farb A. Atlas of Cardiovascular Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1996.

Virmani R, Burke A, Farb A, et al. Cardiovascular Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2001.

1 Virmani R, Burke A, Farb A, et al. Cardiovascular Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2001.

2 Reynen K. Cardiac myxomas. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1610-1617.

3 Grebenc ML, Rosado de Christenson ML, Green CE, et al. Cardiac myxoma: imaging features in 83 patients. RadioGraphics. 2002;22:673-689.

4 Edwards A, Bermudez C, Piwonka G, et al. Carney’s syndrome: complex myxomas: report of four cases and review of the literature. Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;10:264-275.

5 Grebenc ML, Rosado de Christenson ML, Burke AP, et al. Primary cardiac and pericardial neoplasms: radiologic-pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics. 2000;20:1073-1103.

6 Virmani R, Burke A, Farb A. Atlas of Cardiovascular Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1996.

7 Araoz PA, Mulvagh SL, Tazelaar HD, et al. CT and MR imaging of benign primary cardiac neoplasms with echocardiographic correlation. RadioGraphics. 2000;20:1303-1319.

8 Syed IS, Feng D, Harris SR, et al. MR imaging of cardiac masses. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2008;16:137-164.

9 Sparrow PJ, Kurian JB, Jones TR, et al. MR imaging of cardiac tumors. RadioGraphics. 2005;25:1255-1276.

10 Grizzard JD, Ang GB. Magnetic resonance imaging of pericardial disease and cardiac masses. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2007;15:579-607.

11 Gowda RM, Khan IA, Nair CK, et al. Cardiac papillary fibroelastoma: a comprehensive analysis of 725 cases. Am Heart J. 2003;146:404-410.

12 Sun JP, Asher CR, Yang XS, et al. Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of papillary fibroelastomas: a retrospective and prospective study in 162 patients. Circulation. 2001;103:2687-2693.

13 Bootsveld A, Puetz J, Grube E. Incidental finding of a papillary fibroelastoma on the aortic valve in 16 slice multi-detector row computed tomography. Heart. 2004;90:e35.

14 Lembcke A, Meyer R, Kivelitz D, et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine: papillary fibroelastoma of the aortic valve: appearance in 64-slice spiral computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and echocardiography. Circulation. 2007;115:e3-e6.

15 Luna A, Ribes R, Caro P, et al. Evaluation of cardiac tumors with magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Radiol. 2005;15:1446-1455.

16 Shiraishi J, Tagawa M, Yamada T, et al. Papillary fibroelastoma of the aortic valve: evaluation with transesophageal echocardiography and magnetic resonance imaging. Jpn Heart J. 2003;44:799-803.

17 Kelle S, Chiribiri A, Meyer R, et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine: papillary fibroelastoma of the tricuspid valve seen on magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2008;117:e190-e191.

18 Butany J, Nair V, Naseemuddin A, et al. Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:219-228.

19 Burke AP, Rosado de Christenson M, Templeton PA, et al. Cardiac fibroma: clinicopathologic correlates and surgical treatment. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108:862-870.

20 Iqbal MB, Stavri G, Mittal T, et al. A calcified cardiac mass. Int J Cardiol. 2007;115:e126-e128.

21 Cina SJ, Smialek JE, Burke AP, et al. Primary cardiac tumors causing sudden death: a review of the literature. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1996;17:271-281.

22 Isaacs HJr. Fetal and neonatal cardiac tumors. Pediatr Cardiol. 2004;25:252-273.

23 Yan AT, Coffey DM, Li Y, et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine: myocardial fibroma in Gorlin syndrome by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2006;114:e376-e379.

24 De Cobelli F, Esposito A, Mellone R, et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine: late enhancement of a left ventricular cardiac fibroma assessed with gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circulation. 2005;112:e242-e243.

25 Tworetzky W, McElhinney DB, Margossian R, et al. Association between cardiac tumors and tuberous sclerosis in the fetus and neonate. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:487-489.

26 Bader RS, Chitayat D, Kelly E, et al. Fetal rhabdomyoma: prenatal diagnosis, clinical outcome, and incidence of associated tuberous sclerosis complex. J Pediatr. 2003;143:620-624.

27 Uzun O, Wilson DG, Vujanic GM, et al. Cardiac tumours in children. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:11.

28 Burke A, Jeudy JJr, Virmani R. Cardiac tumours: an update. Heart. 2008;94:117-123.

29 Salanitri JC, Pereles FS. Cardiac lipoma and lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum: cardiac magnetic resonance imaging findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28:852-856.

30 Cunningham KS, Veinot JP, Feindel CM, et al. Fatty lesions of the atria and interatrial septum. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1245-1251.

31 Heyer CM, Kagel T, Lemburg SP, et al. Lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum: a prospective study of incidence, imaging findings, and clinical symptoms. Chest. 2003;124:2068-2073.

32 O’Connor S, Recavarren R, Nichols LC, et al. Lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum: an overview. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:397-399.

33 Fan CM, Fischman AJ, Kwek BH, et al. Lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum: increased uptake on FDG PET. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:339-342.

34 Hamilton BH, Francis IR, Gross BH, et al. Intrapericardial paragangliomas (pheochromocytomas): imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:109-113.

35 Mandak JS, Benoit CH, Starkey RH, et al. Echocardiography in the evaluation of cardiac pheochromocytoma. Am Heart J. 1996;132:1063-1066.

36 Lupinski RW, Shankar S, Agasthian T, et al. Primary cardiac paraganglioma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:e43-e44.

37 Reynolds C, Tazelaar HD, Edwards WD. Calcified amorphous tumor of the heart (cardiac CAT). Hum Pathol. 1997;28:601-606.

38 Ho HH, Min JK, Lin F, et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine: calcified amorphous tumor of the heart. Circulation. 2008;117:e171-e172.

39 Fealey ME, Edwards WD, Reynolds CA, et al. Recurrent cardiac calcific amorphous tumor: the CAT had a kitten. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2007;16:115-118.

40 Lewin M, Nazarian S, Marine JE, et al. Fatal outcome of a calcified amorphous tumor of the heart (cardiac CAT). Cardiovasc Pathol. 2006;15:299-302.

41 Bussani R, De Giorgio F, Abbate A, et al. Cardiac metastases. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:27-34.

42 Chiles C, Woodard PK, Gutierrez FR, et al. Metastatic involvement of the heart and pericardium: CT and MR imaging. RadioGraphics. 2001;21:439-449.

43 Odeh M, Oliven A, Misselevitch I, et al. Acute cor pulmonale due to tumor cell microemboli. Respiration. 1997;64:384-387.

44 Borsaru AD, Lau KK, Solin P. Cardiac metastasis: a cause of recurrent pulmonary emboli. Br J Radiol. 2007;80:e50-e53.

45 Poh KK, Avelar E, Hua L, et al. Cardiac metastases from malignant melanoma. Clin Cardiol. 2007;30:359-360.

46 Ozyuncu N, Sahin M, Altin T, et al. Cardiac metastasis of malignant melanoma: a rare cause of complete atrioventricular block. Europace. 2006;8:545-548.

47 Khan N, Golzar J, Smith NL, et al. Intracardiac extension of a large cell undifferentiated carcinoma of lung. Heart. 2005;91:512.

48 Salanitri J. Cardiac metastases: ante-mortem diagnosis with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Intern Med J. 2005;35:303-304.

49 Shanmugam G. Primary cardiac sarcoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29:925-932.

50 Kucukarslan N, Kirilmaz A, Ulusoy E, et al. Eleven-year experience in diagnosis and surgical therapy of right atrial masses. J Card Surg. 2007;22:39-42.

51 Vander Salm TJ. Unusual primary tumors of the heart. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12:89-100.

52 Neragi-Miandoab S, Kim J, Vlahakes GJ. Malignant tumours of the heart: a review of tumour type, diagnosis and therapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2007;19:748-756.

53 Skopin II, Serov RA, Makushin AA, et al. Primary rhabdomyosarcoma of the right atrium. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2003;2:316-318.

54 Uemura S, Watanabe M, Iwama H, et al. Extensive primary cardiac liposarcoma with multiple functional complications. Heart. 2004;90:e48.

55 Rockwell L, Hetzel P, Freeman JK, et al. Cardiac involvement in malignancies, case 3: primary cardiac lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2744-2745.

56 Nakakuki T, Masuoka H, Ishikura K, et al. A case of primary cardiac lymphoma located in the pericardial effusion. Heart Vessels. 2004;19:199-202.

FIGURE 67-1

FIGURE 67-1

FIGURE 67-2

FIGURE 67-2

FIGURE 67-3

FIGURE 67-3

FIGURE 67-4

FIGURE 67-4

FIGURE 67-5

FIGURE 67-5

FIGURE 67-6

FIGURE 67-6

FIGURE 67-7

FIGURE 67-7

FIGURE 67-8

FIGURE 67-8

FIGURE 67-9

FIGURE 67-9

FIGURE 67-10

FIGURE 67-10

FIGURE 67-11

FIGURE 67-11

FIGURE 67-12

FIGURE 67-12

FIGURE 67-13

FIGURE 67-13

FIGURE 67-14

FIGURE 67-14

FIGURE 67-15

FIGURE 67-15

FIGURE 67-16

FIGURE 67-16

FIGURE 67-17

FIGURE 67-17

FIGURE 67-18

FIGURE 67-18

FIGURE 67-19

FIGURE 67-19

FIGURE 67-20

FIGURE 67-20

FIGURE 67-21

FIGURE 67-21

FIGURE 67-22

FIGURE 67-22

FIGURE 67-23

FIGURE 67-23

FIGURE 67-24

FIGURE 67-24

FIGURE 67-25

FIGURE 67-25

FIGURE 67-26

FIGURE 67-26

FIGURE 67-27

FIGURE 67-27

FIGURE 67-28

FIGURE 67-28

FIGURE 67-29

FIGURE 67-29

FIGURE 67-30

FIGURE 67-30

FIGURE 67-31

FIGURE 67-31

FIGURE 67-32

FIGURE 67-32

FIGURE 67-33

FIGURE 67-33

FIGURE 67-34

FIGURE 67-34

FIGURE 67-35

FIGURE 67-35

FIGURE 67-36

FIGURE 67-36

FIGURE 67-37

FIGURE 67-37

FIGURE 67-38

FIGURE 67-38

FIGURE 67-39

FIGURE 67-39

FIGURE 67-40

FIGURE 67-40

FIGURE 67-41

FIGURE 67-41