Cardiac Monitoring

Short- and Long-Term Recording

Ambulatory cardiac monitoring to detect arrhythmia became practical with the development of Holter monitoring and its subsequent derivatives. The clinician is currently armed with an array of tools to provide progressively longer durations of electrocardiographic (ECG) monitoring, to obtain a rhythm profile potentially useful in risk stratification, and to establish a symptom rhythm correlation in patients with infrequent symptoms (Figure 64-1).

Figure 64-1 Ambulatory recording during palpitations and presyncope. Note the burst of atrial tachycardia, with associated brief pauses.

Short-Term Recording

Holter Monitoring

Holter monitoring has several drawbacks. Patients may not experience symptoms or cardiac arrhythmias during the usual Holter recording periods. In patients with syncope, the likelihood of another syncopal episode occurring during the monitoring period is the major limiting factor. Presyncope is a more common event during ambulatory monitoring but is less likely to be associated with an arrhythmia.1,2 The ubiquity of presyncope as a symptom in the community makes its usefulness as a surrogate for syncope relatively uncertain. The physical size of the device may hinder the ability of patients to sleep comfortably or to engage in activities that precipitate symptoms. Patients are further inconvenienced because the devices have to be removed while showering. Observations on Holter monitoring must be correlated with clinical context in the absence of symptoms. Significant variability is often noted in patient documentation of activated events such that accurate symptom–rhythm correlation is undermined.

It is not surprising that Holter monitoring has a low diagnostic yield. In several large series using 12 h or more of ambulatory monitoring for investigation of syncope, only 4% had recurrence of symptoms during monitoring.3,4 The overall diagnostic yield of ambulatory or Holter monitoring was 19%. These studies reported symptoms that were not associated with arrhythmias in 15% of cases. The causal relationship between arrhythmia and syncope was frequently uncertain. Uncommon asymptomatic arrhythmias such as prolonged sinus pauses, atrioventricular block (such as Mobitz type II block), and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia can provide important contributions to the diagnosis, instigating further investigations to rule out structural heart disease and other precipitating factors. Although these observations necessitate prompt attention, it is important to interpret the results in the clinical context of the syncopal presentation and to not unduly exclude common causes of syncope such as neurocardiogenic syncope.

It is also important to understand that a normal Holter monitor does not exclude an arrhythmic cause for syncope. In fact, an arrhythmic cause is typically the case. If the pretest probability is high for an arrhythmic cause, further investigations such as more prolonged monitoring or cardiac electrophysiological studies are required. In a study that evaluated extension of ambulatory Holter monitoring duration to 72 h,5 an increased number of asymptomatic arrhythmias were detected, but the overall diagnostic yield was not increased.

Nonelectrode Event Recorders

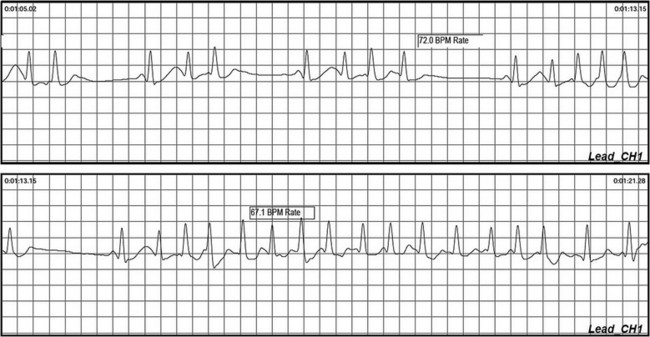

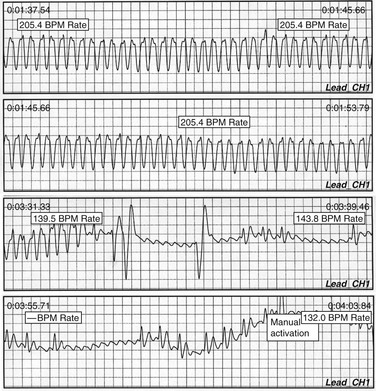

Transtelephonic monitors are a form of noncontinuous ambulatory recording that is convenient for patient use. During symptomatic episodes, the patient activates the device, which then records electrocardiographic signals. The recorded event must be directly transmitted by an analog telephone line to a receiving center (Figures 64-2 and 64-3). The received signal is then converted to an analog recording that is displayed or printed as a single lead rhythm strip. The device has solid-state memory capacity, allowing recording and storage of electrocardiographic signals during symptoms. Electrocardiographic signals are collected prospectively for 1 to 2 minutes upon patient activation. The major disadvantages of such devices include the need for patient activation; missing asymptomatic arrhythmias, which requiring that the symptoms persist long enough for the device to record the event; and the inability to record events that surround the onset of symptoms.

Figure 64-3 External loop recorder download from a patient with near syncope with palpitations. Wide QRS complex tachycardia is noted at 206 bpm, which subsequently demonstrates underlying atrial flutter with much slower conduction, and subsequent patient activation to capture the event. No recognized intervention led to an abrupt reduction in conduction rate.

New Technology

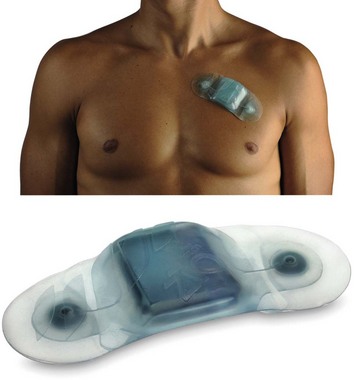

Patch

Emerging technologies such as the iRhythm device promise minimally invasive intermediate-term monitoring without classic electrodes and battery systems, enabling a patch-based “all in one” system to facilitate 7 to 14 d of monitoring (Figure 64-4). These technologies are currently being evaluated with promising early results, but larger-scale or comparative studies have not been performed. Two prospective comparative trials are under way (Holter vs. patch), as is a third trial, which was undertaken to validate detection of asymptomatic atrial fibrillation. Publications are anticipated by the time of the release of this chapter.

Wrist Recorders

Wrist and mobile phone-based recording devices show promise as minimally invasive recording devices, with rapidly evolving technology. A recent preliminary report indicated the potential pulse detection capability of a wrist recording device termed the wriskwatch,6 which brought attention to alternate means of recording multiple physiological parameters.

Intermediate-Duration Monitoring

Extended Holter

Continuous ambulatory monitoring with data transmission to a central monitoring station staffed by Health Professionals (Cardionet, San Diego California) has emerged in the United States as a useful resource to extend traditional Holter monitoring beyond 48 h. This technique is typically used for 7 to 14 d, and has shown incremental benefit over a standard external loop recorder in diagnosing or excluding arrhythmia.7 This approach also provides the added layer of monitoring center involvement, which enhances responsiveness to changes seen during monitoring. Unfortunately, this substantially increases cost.

External Loop Recorders

An external loop recorder continuously records and stores a single external modified limb lead electrogram with a 4- to 18-min memory buffer (see Figure 64-2). After the onset of spontaneous symptoms, the patient activates the device storing the previous 3 to 14 min and the following 1 to 4 min of recorded information. The captured rhythm strip subsequently can be uploaded and analyzed, often providing critical information regarding onset and termination of the arrhythmia (see Figure 64-2). This system theoretically can be used indefinitely, but in practice, use is limited to a few weeks in most individuals because of its limitations. The recording device is connected to skin electrodes on the patient’s chest wall that need to be removed for bathing or showering, and can be uncomfortable during sleep.

A randomized trial has shown diagnostic and cost-effectiveness superiority to Holter monitors (22% symptom–rhythm correlation yield for Holter monitoring vs. 56% for the loop recorder; P < .01).8 An increment in diagnostic yield is noted when automatic activation is added to patient activation.9 Automatic detection includes bradycardia, tachycardia, and pauses, as well as atrial fibrillation based on algorithms that detect RR irregularity. Data on the utility of this technology in detecting or excluding atrial fibrillation are limited.

Vest Technology

Multiple vendors now offer wearable monitoring systems that have the potential to acquire and transmit multiple physiological parameters including ECG. These include vest and shirt technologies using integrated materials for capture of ECG and respiratory parameters.10 Much of this technology has not completed the regulatory process and has not emerged in day-to-day clinical care but promises to revolutionize monitoring technologies. The interested reader is directed to an in-depth review of emerging technologies prepared by Pantelopoulos et al.11

Prolonged Monitoring

Implantable Cardiac Monitors

Implanted loop recorders are manufactured by Medtronic (Reveal XT Model 9529, DX Model 9538, Minneapolis, Minnesota) and by St. Jude Medical (Confirm Model DM2100, Little Canada, Minnesota; Figure 64-5). Both are smaller than a conventional pacemaker generator, record a single-lead ECG without a transvenous lead, and have the potential to deliver 3 years of battery life. The device is typically inserted into the left chest using local anesthetic, usually in a high left parasternal or medial pacemaker insertion location.12 Recent evidence suggests that a simplified implant procedure halfway between the sternal notch and the left breast area on an oblique line consistently results in an adequate signal.13 This observation has not been extensively validated but certainly simplifies the potential need to map for an ideal location. In principle, devices can be implanted anywhere in the chest and abdomen where an ECG can be recorded. The implant procedure is similar to fashioning a small pacemaker pocket. An adequate signal can be obtained anywhere in the left thorax, without the need for cutaneous mapping. Although mapping is advocated, it is seldom performed, and an adequate signal to assess RR intervals is generally obtained. Devices have been implanted in the right parasternal location to optimize P waves, and in an inframammary or anterior axillary location for comfort or cosmetic purposes. These alternate sites typically record a lower-amplitude ECG signal. The patient along with a spouse, family member, or friend is instructed in use of the activator at the time of implant. Sterile implant technique is essential. Prophylactic antibiotics are generally recommended, although efficacy in preventing infection has not been rigorously established.

Clinical Studies

Several studies have demonstrated the feasibility of the ILR in establishing a symptom–rhythm correlation during long-term monitoring in patients with syncope.14–19 Pooled data from nine smaller studies summarized in the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines included 506 patients with unexplained syncope at the end of a complete conventional investigation. A symptom–rhythm correlation was found in 176 patients (35%); of these, 56% had asystole (or bradycardia in a few cases) at the time of the recorded event, 11% had tachycardia, and 33% had no arrhythmia.20

A recent study of a “real-world” experience included 570 patients monitored for diagnosis of syncope.21 Significant physical trauma had been experienced in association with a syncopal episode by 36% of patients. Average follow-up time after ILR implant was 10 ± 6months. Syncope recurred in 19%, 26%, and 36% after 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively. Of 218 events during follow-up, ILR-guided diagnosis was obtained in 170 cases (78%), of which 128 (75%) were cardiac. The median number of tests performed per patient in the total study population was 13, and patients saw an average of 3 consultants before device implant. This speaks to the immense and misguided industry of evaluation of syncope before evaluation is completed by a syncope expert. A structured history followed by targeted investigations including early use of progressive monitoring technologies will lead to a diagnosis in most patients, without the use of very low-yield tests such carotid Doppler or brain imaging.22

Several studies have demonstrated the usefulness of prolonged cardiac monitoring in select populations. The ISSUE investigators (International Study on Syncope of Uncertain Etiology) assessed 111 patients with presumed vasovagal syncope who underwent tilt testing and loop recorder implant, regardless of tilt result.23 Syncope recurred in 34% of patients in both tilt-positive and tilt-negative groups, with marked bradycardia or asystole the most common recorded arrhythmia during follow-up (46% and 62%, respectively). Tilt testing failed to predict recurrence of syncope. The ISSUE2 study performed an ILR implant in 443 patients with recurrent syncope in the absence of structural heart disease, who were presumed to have vasovagal syncope.14 Syncope recurred in 143 patients, with a symptom–rhythm correlation in 102 patients. In those 102 patients, loop recorder–directed therapy (predominantly pacing for bradycardia) was associated with a lower risk of syncope recurrence (10% vs. 41%; P = .0005). This was not a randomized assessment of the benefit of pacing, and it led to the conduct of the ISSUE3 study, wherein 511 patients over age 40 with recurrent vasovagal syncope underwent loop recorder implant. In the 17% with asystolic recurrence, dual-chamber pacemaker therapy was superior to the “pacemaker off” approach in prevention of recurrent syncope (57% reduction; 95% confidence interval [CI], 4% to 81%).24 This suggests that prolonged monitoring with an ILR is useful in patients with frequent vasovagal syncope who are over age 40, if pacemaker therapy is contemplated. This also suggests a diminishing role for tilt testing, which has limited correlation with spontaneous episodes recorded during extended monitoring.

Loop recorders have also shown utility in patients with syncope and bundle branch block with negative electrophysiological testing.25 Negative electrophysiological testing does not exclude a diagnosis of intermittent complete atrioventricular (AV) block, and prolonged monitoring or consideration of permanent pacing is reasonable in this population.26 Syncope in the absence of marked reduction in left ventricular function provides grounds for consideration of an ILR if an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is not indicated and noninvasive testing is inconclusive.27

Two prospective randomized trials compared early use of the loop recorder for prolonged monitoring with conventional testing in patients without significant structural heart disease undergoing a cardiac workup for unexplained syncope.15,28 Conventional testing involved external loop recorders and tilt and electrophysiological testing. Both studies showed a higher diagnostic yield when an ILR was used. Overall, prolonged monitoring was more likely than conventional testing to result in a diagnosis, with a symptom–rhythm correlation obtained in 55% compared with a 19% diagnostic yield in RAST (the Randomized Assessment of Syncope Trial; P = .0014).28 Both studies also showed that up-front use of an implantable strategy was apparently cost-effective compared with conventional testing because of the dramatic improvement in diagnostic yield.15,29 These data highlight the limitations of conventional diagnostic techniques. In patients with infrequent syncope, the ILR is the diagnostic tool of choice, especially when noninvasive testing is negative and an arrhythmia is suspected.

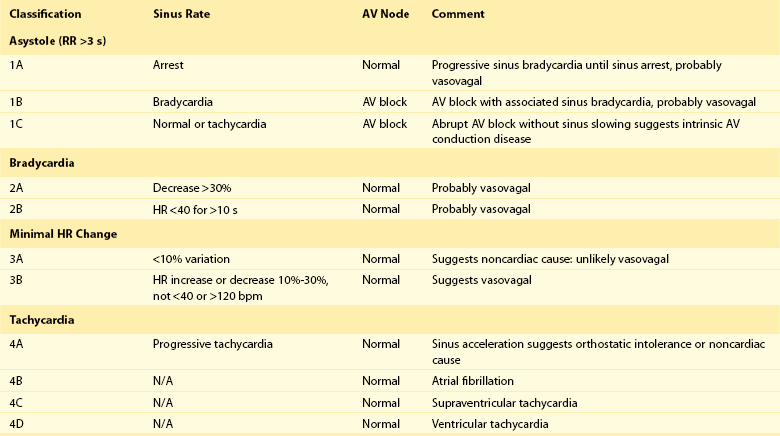

Event Classification

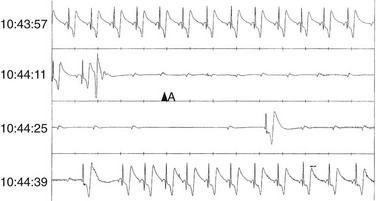

Interrogation of ILRs after recurrence of syncope often demonstrates rhythm findings that require clinical correlation and considerable judgment to interpret (Figure 64-6). Nocturnal pauses or atrial fibrillation may have different implications in patients in accordance with their index indication for monitoring. The ISSUE investigators proposed a useful classification system for symptomatic events in loop recorders applied to patients with syncope,30 which is summarized in Table 64-1. This is often helpful in assigning a probable mechanism of syncope.

Table 64-1

ISSUE Classification of Detected Rhythm from the ILR

AV, Atrioventricular; HR, heart rate; ILR, implantable loop recorder; N/A, not applicable.

Adapted from Reference 17.

Figure 64-6 Rhythm strip from a Medtronic implanted loop recorder from a 77-year-old man with recurrent unexplained syncope and a normal baseline electrocardiogram (ECG). Note that a premature ventricular contraction (PVC) induces persistent complete atrioventricular (AV) block without an escape QRS; this is followed by sinus slowing, suggesting a secondary cardioinhibitory vagal reaction.

Additional Uses of Extended Monitoring Technologies

Long-term cardiac monitoring is best suited to patients with infrequent intermittent symptoms possibly related to arrhythmia, or to those in whom an infrequent “silent” arrhythmia is sought. Although syncope is a logical first application of this technology, many other clinical disease states stand to benefit from the knowledge gained from prolonged monitoring. This includes atypical epilepsy, where seizures may serve as evidence of recurrent cerebral hypoperfusion in conjunction with syncope, mistaken as a primary neurologic event.31

Additional potential uses of the ILR relate to the automatic detection feature of the device in patients for risk stratification after myocardial infarction. The CARISMA study involved implanted ILRs in 297 patients and followed them for 1.9 ± 0.5 years.32 Predefined arrhythmias were recorded in 137 patients (46%), 86% of whom were asymptomatic. The ILR documented a 28% incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation, a 13% incidence of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (≥16 beats), a 10% incidence of high-degree atrioventricular block, a 12% incidence of significant sinus node disease, a 3% incidence of sustained ventricular tachycardia, and a 3% incidence of ventricular fibrillation. Regression analysis showed that high-degree atrioventricular block was the most powerful predictor of cardiac death. The implications of this study are not completely understood, and the ability to alter outcomes remains to be established. It certainly demonstrates the incremental detection ability of the ILR in this population, suggesting that historic short-term studies have grossly underestimated the incidence of potentially relevant arrhythmias. Active research in this realm is ongoing.

Finally, strong interest in silent atrial fibrillation as a cause of stroke has led to the initiation of several studies to determine the presence of asymptomatic atrial fibrillation. Multiple small studies have evaluated the usefulness of external monitoring technologies after ablation, and several larger studies with implanted devices measuring both burden of disease and efficacy of an antiarrhythmic intervention are expected to report imminently.33 Although these studies have reported a higher rate of silent atrial arrhythmias than was previously suspected, the implications of these findings are speculative. A potential use of this technology may involve detecting atrial fibrillation in patients who have discontinued otherwise indicated antithrombotic therapy, in cases where the presence of atrial fibrillation would prompt resumption of therapy. This is an emerging focus of study, particularly in the context of the new generation of antithrombotic therapies with rapid therapeutic onset and offset, in conjunction with the prospect of smaller, easier to implant monitoring devices.

Indications for Prolonged Monitoring

Loop recorders are suited to earlier implementation in the diagnostic cascade of syncope, in part because of the low yield of other tests incremental to a thoughtful clinical evaluation. As stated in the ESC guidelines and in the Canadian Position Statement on Syncope, patients with unexplained syncope with a high likelihood of recurrence of syncope within 3 years who are at low risk of sudden death should be considered for an implanted monitor.20,34 An ILR should also be considered in high-risk patients if thorough evaluation has not demonstrated a cause of syncope (supine or exertional syncope, family history of sudden death, preexcited QRS, or repolarization abnormality suggesting an inherited syndrome with risk of sudden death).

References

1. Olson, JA, Fouts, AM, Padanilam, BJ, et al. Utility of mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry for the diagnosis of palpitations, presyncope, syncope, and the assessment of therapy efficacy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007; 18:473–477.

2. Krahn, AD, Klein, GJ, Yee, R, et al. Predictive value of presyncope in patients monitored for assessment of syncope. Am Heart J. 2001; 141:817–821.

3. Linzer, M, Yang, EH, Estes, NA, et al. Diagnosing syncope. Part 1. Value of history, physical examination, and electrocardiography. Clinical Efficacy Assessment Project of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1997; 126:989–996.

4. Subbiah, R, Gula, LJ, Klein, GJ, et al. Syncope: Review of monitoring modalities. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2008; 4:41–48.

5. Bass, EB, Curtiss, EI, Arena, VC, et al. The duration of Holter monitoring in patients with syncope. Is 24 hours enough? Arch Intern Med. 1990; 150:1073–1078.

6. Rickard, J, Ahmed, S, Baruch, M, et al. Utility of a novel watch-based pulse detection system to detect pulselessness in human subjects. Heart Rhythm. 2011; 8:1895–1899.

7. Rothman, SA, Laughlin, JC, Seltzer, J, et al. The diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmias: A prospective multi-center randomized study comparing mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry versus standard loop event monitoring. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007; 18:241–247.

8. Sivakumaran, S, Krahn, AD, Klein, GJ, et al. A prospective randomized comparison of loop recorders versus Holter monitors in patients with syncope or presyncope. Am J Med. 2003; 115:1–5.

9. Reiffel, JA, Schwarzberg, R, Murry, M. Comparison of autotriggered memory loop recorders versus standard loop recorders versus 24-hour Holter monitors for arrhythmia detection. Am J Cardiol. 2005; 95:1055–1059.

10. Pandian, PS, Mohanavelu, K, Safeer, KP, et al. Smart Vest: Wearable multi-parameter remote physiological monitoring system. Med Eng Phys. 2008; 30:466–477.

11. Pantelopoulos, A, Bourbakis, N. A survey on wearable biosensor systems for health monitoring. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2008; 2008:4887–4890.

12. Krahn, AD, Klein, GJ, Yee, R, et al. Maturation of the sensed electrogram amplitude over time in a new subcutaneous implantable loop recorder. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1997; 20:1686–1690.

13. Grubb, BP, Welch, M, Kanjwal, K, et al. An anatomic-based approach for the placement of implantable loop recorders. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2010; 33:1149–1152.

14. Brignole, M, Sutton, R, Menozzi, C, et al. Early application of an implantable loop recorder allows effective specific therapy in patients with recurrent suspected neurally mediated syncope. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27:1085–1092.

15. Farwell, DJ, Freemantle, N, Sulke, N. The clinical impact of implantable loop recorders in patients with syncope. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27:351–356.

16. Krahn, AD, Klein, GJ, Yee, R, et al. Detection of asymptomatic arrhythmias in unexplained syncope. Am Heart J. 2004; 148:326–332.

17. Farwell, DJ, Freemantle, N, Sulke, AN. Use of implantable loop recorders in the diagnosis and management of syncope. Eur Heart J. 2004; 25:1257–1263.

18. Krahn, AD, Klein, GJ, Fitzpatrick, A, et al. Predicting the outcome of patients with unexplained syncope undergoing prolonged monitoring. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002; 25:37–41.

19. Solano, A, Menozzi, C, Maggi, R, et al. Incidence, diagnostic yield and safety of the implantable loop-recorder to detect the mechanism of syncope in patients with and without structural heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2004; 25:1116–1119.

20. Moya, A, Sutton, R, Ammirati, F, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J. 2009; 30:2631–2671.

21. Edvardsson, N, Frykman, V, van Mechelen, R, et al. Use of an implantable loop recorder to increase the diagnostic yield in unexplained syncope: Results from the PICTURE registry. Europace. 2011; 13:262–269.

22. Pires, LA, Ganji, JR, Jarandila, R, et al. Diagnostic patterns and temporal trends in the evaluation of adult patients hospitalized with syncope. Arch Intern Med. 2001; 161:1889–1895.

23. Moya, A, Brignole, M, Menozzi, C, et al. Mechanism of syncope in patients with isolated syncope and in patients with tilt-positive syncope. Circulation. 2001; 104:1261–1267.

24. Brignole, M, Menozzi, C, Moya, A, et al. Pacemaker therapy in patients with neurally mediated syncope and documented asystole: Third International Study on Syncope of Uncertain Etiology (ISSUE-3): A randomized trial. Circulation. 2012; 125:2566–2571.

25. Brignole, M, Menozzi, C, Moya, A, et al. Mechanism of syncope in patients with bundle branch block and negative electrophysiological test. Circulation. 2001; 104:2045–2050.

26. Krahn, AD, Morillo, CA, Kus, T, et al. Empiric pacemaker compared with a monitoring strategy in patients with syncope and bifascicular conduction block—Rationale and design of the Syncope: Pacing or Recording in ThE Later Years (SPRITELY) study. Europace. 2012; 14:1044–1048.

27. Menozzi, C, Brignole, M, Garcia-Civera, R, et al. Mechanism of syncope in patients with heart disease and negative electrophysiologic test. Circulation. 2002; 105:2741–2745.

28. Krahn, AD, Klein, GJ, Yee, R, et al. Randomized assessment of syncope trial: conventional diagnostic testing versus a prolonged monitoring strategy. Circulation. 2001; 104:46–51.

29. Krahn, AD, Klein, GJ, Yee, R, et al. Cost implications of testing strategy in patients with syncope: Randomized assessment of syncope trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003; 42:495–501.

30. Brignole, M, Moya, A, Menozzi, C, et al. Proposed electrocardiographic classification of spontaneous syncope documented by an implantable loop recorder. Europace. 2005; 7:14–18.

31. Zaidi, A, Clough, P, Cooper, P, et al. Misdiagnosis of epilepsy: Many seizure-like attacks have a cardiovascular cause. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000; 36:181–184.

32. Bloch Thomsen, PE, Jons, C, Raatikainen, MJ, et al, Long-term recording of cardiac arrhythmias with an implantable cardiac monitor in patients with reduced ejection fraction after acute myocardial infarction: The Cardiac Arrhythmias and Risk Stratification After Acute Myocardial Infarction (CARISMA) study. Circulation Sep 28. 2010(122):1258–1264.

33. Arya, A, Piorkowski, C, Sommer, P, et al. Clinical implications of various follow up strategies after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007; 30:458–462.

34. Sheldon, RS, Morillo, CA, Krahn, AD, et al. Standardized approaches to the investigation of syncope: Canadian Cardiovascular Society position paper. Can J Cardiol. 2011; 27:246–253.