Chapter 46

Cardiac Manifestations of HIV/AIDS

1. How have the cardiac manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) changed over the years?

2. What are HIV-related cardiac complications?

Pericardial effusion/tamponade

Pericardial effusion/tamponade

Dilated cardiomyopathy (systolic and diastolic dysfunction)

Dilated cardiomyopathy (systolic and diastolic dysfunction)

Marantic (thrombotic) or infectious endocarditis

Marantic (thrombotic) or infectious endocarditis

3. How common is pericardial effusion?

4. Is HIV myocarditis or cardiomyopathy common?

In different series, one-third to one-half of patients in the pre-HAART era (or where HAART therapy was not available) dying of AIDS had lymphocytic infiltration at autopsy. Of these patients, 80% had no other pathogens identified. Additionally, up to 10% of endomyocardial specimens in HIV patients have evidence of other infections (e.g., Coxsackie B, Epstein-Barr virus, adenovirus, and cytomegalovirus).

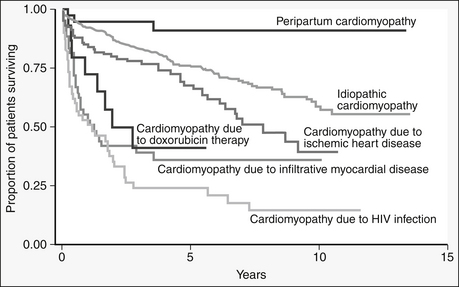

HIV is thought to cause myocarditis from direct action of HIV on myocytes or indirectly through toxins. Patients with HIV and cardiomyopathy have a worse prognosis than those with cardiomyopathy due to other causes of cardiomyopathy (Fig. 46-1). Heart failure caused by HIV-associated left ventricular dysfunction is most commonly found in patients with the lowest CD4 counts and is a marker of poor prognosis. Despite the association of HIV and myocarditis and cardiomyopathy, in patients with HIV and with cardiomyopathy, other possible causes of heart failure (e.g., ischemic, valvular, and toxin-related heart failure) should be excluded.

Figure 46-1 Variable survival in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, depending on underlying etiologic basis. (From Felker GM, Thompson RE, Hare JM, et al: Underlying causes and long-term survival in patients with initially unexplained cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 342:1077, 2000.) HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus.

5. How is HIV cardiomyopathy treated?

6. Why is infective valvular endocarditis a rarity in AIDS?

7. What malignancies can affect the heart in AIDS/HIV?

Kaposi sarcoma is associated with herpesvirus 8 in homosexual AIDS patients. This tumor is often found in the subepicardial fat around surface coronary arteries. About 25% of AIDS patients with systemic Kaposi sarcoma had incidental cardiac involvement, with death as a result of underlying opportunistic infections. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is more common in HIV-positive patients, with a poor prognosis. Leiomyosarcoma is rarely associated with Epstein-Barr virus in AIDS patients.

8. Can nutritional deficiencies be responsible for HIV myopathy?

9. How common is HIV-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)?

10. How should HIV patients be screened for coronary artery disease?

11. What is the pathology of accelerated atherosclerosis in HIV patients?

12. What is the pathophysiology of accelerated atherosclerosis in HIV patients?

The relative risk of myocardial infarction (MI) in HIV patients compared to non-HIV patients is increased by 1.7- to 1.8-fold, and may increase further with increasing age. There is a complex relationship between HIV-related side effects, ART-related side effects, and traditional risk factors that result in a higher prevalence of atherosclerotic disease in HIV patients. ART is associated with increased visceral adiposity, insulin resistance, and abnormal glucose tolerance, therefore increasing the risk of CVD. Traditional risk factors such as hypertension (which may be associated with ART use) and tobacco use are highly prevalent in this population. HIV infection is known to lead to a state of increased inflammation, which has been identified as a factor for early atherosclerosis. HIV infection directly leads to endothelial dysfunction and HIV envelope proteins have been linked to higher levels of endothelin-1 concentrations. In fact, the level of viremia and CD4 counts are predictive of cardiovascular disease.

13. What dyslipidemias occur with HIV disease?

14. What are the effects of ART on cardiovascular risk?

Many ARTs have been associated with dyslipidemia (Table 46-1). Protease inhibitors (PIs) are associated with a small to moderate increase in total cholesterol and LDL and a significant rise in triglyceride levels. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) are associated with dyslipidemia, but less so than are PIs. They typically result in a small increase in total cholesterol, LDL, as well as HDL (which is potentially beneficial). In general, the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) have been associated with insulin resistance and the lipid profile changes are less severe than with PIs and NNRTIs. While PIs and NNRTIs have well-established effects on lipid profiles, the new agents such as fusion inhibitors, chemokine inhibitors, or integrase inhibitors have not shown these changes.

TABLE 46-1

ANTIRETROVIRAL THERAPIES AND THEIR EFFECTS ON LIPID PROFILES AND CARDIOVASCULAR RISK

| Protease Inhibitors (PIs) | Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs) | Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs) |

| TC, LDL ↑; TG ↑↑ | TC, LDL, HDL sl ↑ | Insulin resistance, TC, LDL sl ↑ |

| Atazanavir | Efavirenz | Stavudine |

| Ritonavir | Nevirapine | Tenofovir |

| Tipranavir | Etravirine | Abacavir |

| Darunavir | ||

| Lopinavir | ||

| Saquinavir | ||

| Fosamprenavir | ||

| Nelfinavir |

15. What is acquired lipodystrophy?

This is a disorder characterized by selective loss of adipose tissue from subcutaneous areas of the face, arms, and legs, with redistribution to the posterior neck (buffalo hump) and visceral abdomen. Visceral adiposity is associated with increased inflammatory markers. Lipodystrophy is also associated with attendant development of diabetes mellitus (DM), dyslipidemia, hepatic steatosis, hypertension, and acanthosis nigricans. It can occur in 20% to 40% of HIV patients taking PIs for more than 1 to 2 years. Exercise, with or without treatment with metformin, has been reported to improve body composition in patients with lipodystrophy.

16. How are these dyslipidemias treated?

17. Can cardiothoracic surgery be performed safely in HIV patients?

18. What oral hypoglycemics are recommended?

19. What other drugs used in AIDS/HIV treatment can have cardiac complications?

20. What is the risk of mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV?

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Barbaro, G. Heart and HAART: Two sides of the coin for HIV-associated cardiology issues. World J Cardiol. 2010;2:53–57.

2. Barbazo, G., Lipshultz, S.E. Pathogenesis of HIV-associated cardiomyopathy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;946:57–81.

3. Cicallini, S., Almodovar, S., Grilli, E., Flores, S. Pulmonary hypertension and human immunodeficiency virus infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical approach. Clin Microbio Infect. 2011;17:25–33.

4. Cotter, B.R. Epidemiology of HIV cardiac disease. Progress Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;45:319–326.

5. Duggal, S., Chugh, T.D., Duggal, A.S. 2011 HIV and malnutrition. Clinical and Developmental Immunology. 2012:1–8.

6. Feeney, E., Mallon, P.W.G. HIV and HAART-associated Dyslipidemia. The Open Cardiovascular Medicine Journal. 2011;5:49–63.

7. Friis-Moller, N., Reiss, P., Sabin, C.A., et al. Class of antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1723–1735.

8. Green, M.I. Evaluation and management of dyslipidemia in patients with HIV infection. J Gen Int Med. 2002;17:797–810.

9. Grinspoon, S.K., Grunfeld, C., Kotler, D.P., et al. State of the Science Conference: initiative to decrease cardiovascular risk and increase quality of care for patients living with HIV/AIDS, Executive summary. Circulation. 2008;118:198–210.

10. Hakeen, A., Bhatti, S., Cilingiroglu, M. The Spectrum of Atherosclerotic Coronary Artery Disease in HIV Patients. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2010;12:119–124.

11. Ho, J.E., Hsue, P.Y. Cardiovascular manifestations of HIV infection. Heart. 2009;95:1193–1202.

12. Hsue, P.Y., Waters, D.D. What a Cardiologist Needs to Know about Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. Circulation. 2005;112:3947–3957.

13. Janda, S., Quon, B.S., Swiston, K. HIV and pulmonary arterial hypertension: a systematic review. HIV Medicine. 2010;11:620–634.

14. Katz, A.S., Sadaniantz, A. Echocardiography in HIV cardiac disease. Progress Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;45:285–292.

15. Luzuriaga, K. Mother-to-child Transmission of HIV: A Global Perspective. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2007;9:511–517.

16. Malvestuttom, C., Aberg, J. Coronary heart disease in people infected with HIV. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 2010;77:547–556.

17. Nakazono, R., Jeudy, J., White, C. HIV-related cardiac complications: CT and MRI findings 2012;198:364–364