56 Cardiac Imaging and Stress Testing

• Cardiac imaging and stress testing are key components of any comprehensive patient evaluation for possible acute coronary syndromes or coronary heart disease.

• Exercise or pharmacologic stress testing is used to risk-stratify patients and determine the presence of stress-induced ischemia.

• Rest myocardial perfusion imaging assesses for ischemia during symptoms at the time of evaluation, whereas stress testing evaluates for stress-induced (exercise or pharmacologic) ischemia.

• Rest myocardial perfusion imaging can be a useful tool for risk stratification and diagnosis in patients with active or recent chest discomfort (<2 hours).

• Echocardiography can be used to assess global cardiac function and may be performed with the patient at rest or with stress.

• Electron beam computed tomography is gaining momentum as an imaging technology that is potentially useful in the emergency department environment.

• Several chest pain unit protocols using various combinations of cardiac biomarkers, imaging modalities, stress testing, and time courses of evaluation have proved successful in many environments.

• Individual institutions and their emergency departments should develop their own custom protocols to best care for patients in that community given the resources available, personnel, and practice patterns.

Background and Scope

The diverse group of patients with symptoms of chest discomfort remains a significant challenge for the emergency physician (EP). High-risk patients with classic angina and young, low-risk patients with atypical symptoms represent only a fraction of those with chest discomfort seem in the everyday emergency department (ED) setting. Frequently, patients have one or two risk factors and some but not all of the classic ischemic symptoms, and the findings on an electrocardiogram (ECG) are nondiagnostic. These patients carry up to a 10% chance of significant cardiac disease and need appropriate risk stratification and diagnostic evaluation.1 As EPs, our goal is not to diagnose the condition of coronary heart disease but, rather, to stratify patients’ risk and identify those at risk for imminent cardiac ischemia and poor outcomes.

EPs use several methods and modalities to evaluate this very heterogenous patient group, each of which has benefits and limitations. Aside from a comprehensive history and physical examination, standard adjuncts include an ECG, serial cardiac biomarker measurements, and some choice of cardiac imaging. The ECG, though often considered the principal diagnostic tool in cardiac evaluation, is the most basic and rapid way to image the heart. Elevations in available cardiac biomarkers indicate the end result of ischemic myocardium and signify myocardial necrosis or cell death. Cardiac imaging indirectly reflects cardiac anatomy and tissue function with the goal of revealing occult cellular ischemia at risk for cell death. Cardiac imaging can be performed with the patient at rest or under physical or pharmacologic stress. Some of the factors to be considered for the appropriate choice of imaging modality include patient selection, exposure to radiation (Table 56.1), and availability of reagents, technology, and personnel to perform the study and interpret the results.2 The goal of this chapter is to familiarize the reader with common cardiac imaging modalities used in the ED for the evaluation of this difficult and high-risk population.

Table 56.1 Approximate Radiation Exposure with Common Imaging Studies as Part of Cardiac Evaluation

| STUDY | MEAN EFFECTIVE DOSE (MILLISIEVERTS) |

|---|---|

| Chest radiograph | 0.02 |

| Echocardiogram | 0 |

| Myocardial perfusion imaging | 15 |

Ventilation-perfusion ( ) scan ) scan |

1.2-2 |

| Computed tomographic (CT) angiography of the chest (noncoronary) | 15 |

| CT angiography (coronary) | 8-15 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 7-15 |

Adapted from Fazel R, Krumholz HM, Wang Y, et al. Exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation from medical imaging procedures. N Engl J Med 2009;361:849–57.

Electrocardiogram

An ECG should be obtained within 10 minutes of a patient’s arrival at the ED.3 Though often considered to be the most important diagnostic and prognostic tool available, ECGs rather primitively indicate only gross electrical derangements caused by dead or dying muscle tissue. Serial ECGs during progression or regression of a patient’s symptoms can be helpful, similar to procuring prior ECGs from a previous medical visit.

Chest Roentgenogram

Though not usually considered to be a cardiac imaging modality, the chest radiograph is an important diagnostic tool in the evaluation of patients with chest pain. Probably the most useful function of the chest radiograph lies in identifying or suggesting alternative diagnoses for the patient’s symptoms. Chest radiographs are safe and result in relatively low radiation exposure (0.02 millisievert) when compared with the cardiac-specific modalities (see Table 56.1). Pneumothorax or pneumonia can be identified on a chest radiograph. Mediastinal widening, apical capping of pleural fluid, tracheal deviation, or displacement of intimal calcium from the outer vessel wall may indicate aortic dissection. An enlarged cardiac silhouette may signify the presence of a pericardial effusion or, if seen together with pulmonary congestion, congestive heart failure. Pulmonary emboli may be accompanied by focal oligemia, wedge-based densities, or enlarged pulmonary arteries on chest radiographs. Every patient with chest discomfort should have a chest radiograph taken before additional evaluation.

Exercise Treadmill Testing

Graded exercise testing is a popular method of cardiac stress testing in both the inpatient and outpatient settings. Many of the early ED accelerated diagnostic protocols used this test after initial risk stratification via cardiac biomarkers and the ECG.4–8 This was the beginning of chest pain unit protocols and the ability to appropriately risk-stratify ED patients with chest pain within 6 to 12 hours. Outcomes at 6 to 12 months have been found to be similar with very few adverse events between patients admitted to the hospital and those cared for in an ED chest pain unit setting. Although exercise treadmill testing has a lower positive predictive value (great proportion of false-positive results) than some other more contemporary myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) modalities, its use still diminishes unnecessary admissions.9

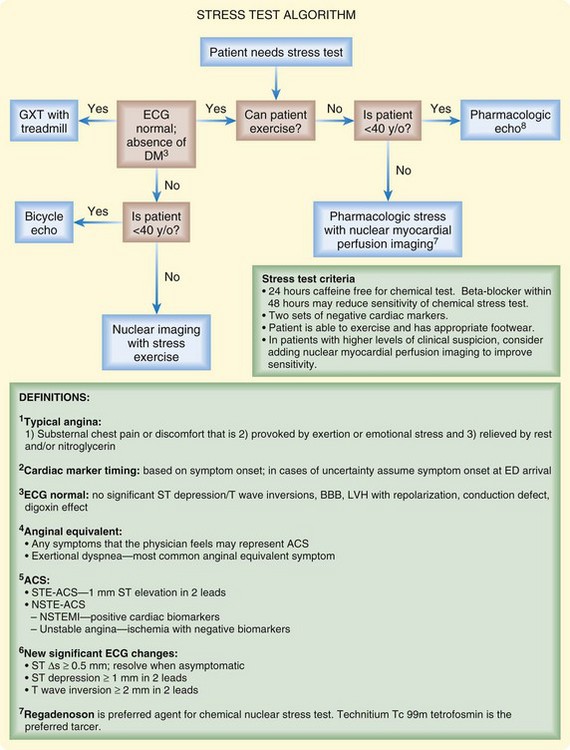

Selection criteria for exercise testing are more restrictive than those for other imaging modalities. Patients must be able to walk on a treadmill, and findings on the ECG should be normal or show no new changes. Agents such as dobutamine, dipyridamole, adenosine, or regadenoson can be used in lieu of exercise. Although exercise testing is slowly being supplanted by studies offering more detailed functional information, it is still a major tool in many centers (Fig. 56.1).

Echocardiography

Rest Echocardiogram

Two-dimensional rest echocardiography enables real-time visualization of the anatomy and physiology of the heart and thereby provides an abundant amount of diagnostic information in patients seen in the ED. The procedure itself is safe, painless, and without radiation. In some patients with chest pain, a rest echocardiogram is a sensitive bedside test that can be an important tool in guiding diagnosis, therapeutic interventions, and final disposition of the patient. Echocardiography is a comprehensive diagnostic tool for a number of conditions, including cardiac ischemia, acute pulmonary embolism, pericardial effusion, aortic dissection, pericarditis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, mitral valve prolapse, and aortic stenosis (Box 56.1).

Rest echocardiography has an important role in risk stratification of patients in the ED with potential myocardial ischemia. In a healthy heart, increases in heart rate and myocardial contractility are seen with cardiac stress. In patients with myocardial ischemia, segmental changes can be seen with rest echocardiography, including decreased wall thickness during stress, a decrease or no change in the ejection fraction, and regional wall motion abnormalities. The diagnostic accuracy of rest echocardiography depends on several factors, including proximity in time to the patient’s symptoms, size of the myocardium affected, depth of the ischemic myocardial tissue, and limitations of the specific-generation technology being used. For these reasons, several studies have reported widely varying positive predictive (31% to 100%) and negative predictive (57% to 98%) values for detecting myocardial ischemia in the acute setting.10 Preliminary data indicate a potential ED use of echocardiographic contrast agents, which are absorbed by healthy myocardium and thereby more able to identify subtle regional wall motion abnormalities.11 Finally, EPs are continuing to gain prowess in bedside ultrasonography. However, at this point, focused cardiac ultrasound by EPs includes only a binary assessment (normal versus depressed) of global cardiac function.12

Stress Echocardiogram

Stress echocardiography provides additional diagnostic capability in detecting inducible wall motion abnormalities in patients who may have normal wall motion at rest. A stress echocardiogram can be performed immediately after the patient undergoes physical stress through the use of a treadmill or bike. Alternatively, if the patient is unable or unwilling to undergo exercise, pharmacologic stress with agents such as dobutamine can be used. Dobutamine is an adrenergic-stimulating agent that raises myocardial oxygen demand by increasing contractility, blood pressure, and heart rate. Dobutamine stress echocardiography (DSE) has performed well in providing excellent negative predictive value (NPV) for the diagnosis of obstructive coronary artery disease.13–15 The greatest diagnostic benefit of stress echocardiography is to provide prognostic information in patients with an intermediate pretest probability of having coronary artery disease. This may include patients with some combination of coronary risk factors (hypertension, smoking history, diabetes) and atypical angina, patients with typical angina without risk factors, and patients with abnormal baseline ECG findings. Studies have shown that these patients can be safely discharged from the ED with outpatient follow-up if the results of DSE are negative. In one ED study, DSE had NPVs of 98.8% for all cardiac events (hospital admission for angina and revascularization procedure) and 99.6% for hard cardiac events (cardiac death and nonfatal myocardial infarction).7 In several other studies, the NPV of DSE in patients undergoing ED chest pain protocols ranged from 91% to 96% for cardiac events at 6 months.13–15

Myocardial Perfusion Imaging

MPI has gained wide acceptance for the diagnosis of myocardial ischemia in a variety of patient populations traditionally difficult to diagnose, such as women, asymptomatic diabetic patients, patients with existing ECG abnormalities such as left bundle branch block, and patients with severe renal disease. Gated single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) with an attenuation correction has made MPI even more valuable in the ED setting. With multihead SPECT systems, imaging can often be completed in less than 10 minutes. Also with SPECT, inferior and posterior abnormalities and small areas of infarction can be identified, as well as the occluded blood vessels and the mass of infarcted and viable myocardium. Several landmark trials have shown a high NPV for MPI in the ED evaluation of chest discomfort.16–18 Although thallium imaging is more established, the diffusion kinetics of technetium Tc 99m makes it more desirable in the ED setting.

Electron Beam Computed Tomography and Computed Tomographic Coronary Angiography

Multidetector CT, also known as “ultrafast” CT or CT angiography, has emerged as a highly sensitive means by which to detect calcium in the atherosclerotic lesions of coronary arteries. In addition, CT coronary angiography using 64-slice scanners can accurately visualize the coronary arteries in a large majority of patients. The results are typically given as a calcium score, which does not reflect a potential acute thrombus. CT also imparts the additive advantage of being able to visualize other potentially significant conditions, such as pulmonary embolism and aortic dissection (“triple rule out”).19 Both these modalities show promise in the risk stratification of low- to moderate-risk patients with chest pain.20,21 Possible limitations include availability of this technology and radiologists or cardiologists to read these studies in real time. The previous requirement of lowering the patient’s heart rate grows less necessary with advanced multislice and source technologies. The results from ongoing studies will help determine the optimal role of CT in cardiac evaluation.22

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Current research continues to explore new and hopefully more effective imaging strategies for the evaluation of patients with chest discomfort in the ED. MRI can be used to determine both myocardial perfusion and regional wall motion abnormalities, including transient stunning after an ischemic event. Several studies have shown its utility in the diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome, and recent clinical trials have demonstrated its potential value in identifying atherosclerotic lesions and vulnerable plaque.23,24 We currently believe that limited availability and high cost preclude MRI from becoming a standard, acceptable modality until further studies demonstrate a decisive advantage over nuclear imaging or echocardiography.25

Tips and Tricks

Meet the patient’s expectations by explaining the process and time requirements for a comprehensive risk stratification protocol.

Even after a negative rest protocol result, be sure to emphasize to the patient the need to pursue further stress testing and risk factor modification.

Determine the patient’s ability to exercise before sending the patient for an exercise study. Many patients cannot exercise sufficiently for adequate results and ultimately need pharmacologically induced stress to maintain their heart rate in the appropriate range.

Example of a Chest Pain Unit Protocol That Uses Risk Stratification and Cardiac Imaging

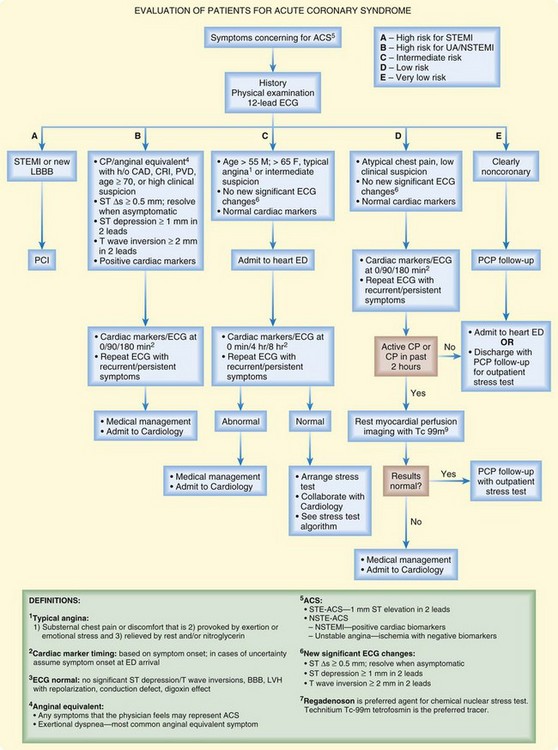

Each institution should develop cardiac evaluation protocols based on the risk profile of its population and the availability of imaging modalities and in collaboration with emergency medicine, radiology, and cardiology physicians. Specific protocols and imaging modalities vary among locations and institutions. Figure 56.2 shows an example of a chest pain unit protocol at a large urban center.

![]() Facts and Formulas

Facts and Formulas

The myocardium takes up technetium 99m proportional to blood flow; unlike thallium 201, technetium 99m is redistributed minimally after injection. This feature allows delayed imaging after the initial radioisotope injection.

Perfusion defects signify areas of acute ischemia, acute infarction, or old scar and hence have to be interpreted cautiously in patients with a preexisting history of acute coronary syndrome or coronary artery disease.

Radiation exposure with different cardiac imaging techniques varies widely and should be a consideration in the most appropriate choice for each patient. Such exposure is particularly important in patients who undergo multiple or repeated studies. See Table 56.1.

Contemporary 64-slice computed tomography (CT) scanners generate images with the spatial resolution of 0.4 mm and a temporal resolution of 83 to 165 msec. Although traditional coronary angiography has a spatial resolution of 0.15 mm and a temporal resolution of 0.33 sec, CT angiography can yield sufficient diagnostic data in many patients. To facilitate adequate imaging for CT angiography, patients may undergo beta-blocker therapy to achieve a heart rate of approximately 60 beats/min.

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Patients experiencing chest discomfort with or without the classic associated symptoms should call their emergency response system (i.e., 911) instead of driving to the nearest hospital.

To provide appropriate risk stratification, chest discomfort evaluation protocols may take several hours to finish.

A right-sided infarction and posterior infarction are separate clinical entities identified by separate and specific electrocardiographic findings.

Even after a negative rest imaging evaluation result, the patient should arrange for further risk assessment and stress imaging with a primary care physician or cardiologist.

Therapeutic lifestyle modifications and attention to modifiable cardiac risk factors should be part of any evaluation protocol.

The patient should keep copies of the imaging records, including a copy of the latest electrocardiogram, in a personal health file. These records can be tremendously useful to other physicians if further emergency cardiac evaluation is required.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

For nuclear imaging, the best results are obtained if the radionuclide is injected while the patient is experiencing symptoms or is undergoing exercise or pharmacologic stress.

Many protocols for stress testing preclude proximate caffeine ingestion. Make sure to note the patient’s prior caffeine intake and to have the patient avoid the inadvertent ingestion of any caffeine-containing product (regular or decaffeinated coffee, tea, soft drinks, and chocolate) during the initial evaluation phase.

Know the difference in the electrocardiographic findings of an inferior, right ventricular, and posterior infarction.

The pharmacy or nuclear medicine department regulates the supply of any nuclear imaging agent. If these agents are unused for a time, they expire and must be discarded. Additional preparation or acquisition of fresh agent may cause the work-up of an individual patient to be delayed.

Even if the cardiac imaging and evaluation results are negative, alternative diagnoses such as aortic dissection, peptic ulcer disease, and pulmonary embolism should be considered. Patients should leave the emergency department with some idea about what may be causing their symptoms.

Two nuclear imaging studies, such as a technetium Tc 99m sestamibi scan and a ventilation-perfusion ( ) lung scan, cannot be performed within the same 24-hour period. If the differential diagnosis includes pulmonary embolism, alternative and complementary imaging modalities may have to be used.

) lung scan, cannot be performed within the same 24-hour period. If the differential diagnosis includes pulmonary embolism, alternative and complementary imaging modalities may have to be used.

Exercise and pharmacologic stress studies require that the patient’s heart rate rise to appropriate levels. The emergency physician should be cautious about starting beta-blocker therapy in patients who will undergo stress studies in the emergency department. Although beta-blockade is a standard treatment in patients with myocardial ischemia, it can hamper the physician’s ability to perform risk stratification for low-risk patients because it results in nondiagnostic stress evaluations.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

A description of the patient’s symptoms should include onset, duration, severity, location, quality, context, associated symptoms, and modifying factors.

Documentation of a past family history of early coronary heart disease or acute coronary syndromes provides useful risk stratification information.

A social history of smoking or the use of cocaine should be documented.

Nuclear imaging documentation should include the patient’s last episode of chest discomfort, particularly whether a radiopharmaceutical was injected during the chest discomfort.

The clinician needs to justify an extended period of evaluation by documenting the need for further risk stratification and observation.

1 Blomkalns AL, Gibler WB. Chest pain unit concept: rationale and diagnostic strategies. Cardiol Clin. 2005;23:411–421. v

2 Fazel R, Krumholz HM, Wang Y, et al. Exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation from medical imaging procedures. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:849–857.

3 Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, et al. 2007 Focused update of the ACC/AHA 2004 guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:210–247.

4 Ramakrishna G, Milavetz JJ, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Effect of exercise treadmill testing and stress imaging on the triage of patients with chest pain: CHEER substudy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:322–329.

5 Lewis WR, Amsterdam EA. Utility and safety of immediate exercise testing of low-risk patients admitted to the hospital for suspected acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74:987–990.

6 Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Bricker JT, et al. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for exercise testing: summary article. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1997 Exercise Testing Guidelines). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1531–1540.

7 Diercks DB, Gibler WB, Liu T, et al. Identification of patients at risk by graded exercise testing in an emergency department chest pain center. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:289–292.

8 Amsterdam EA, Kirk JD, Diercks DB, et al. Immediate exercise testing to evaluate low-risk patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:251–256.

9 Amsterdam EA, Kirk JD, Diercks DB, et al. Exercise testing in chest pain units: rationale, implementation, and results. Cardiol Clin. 2005;23:503–516. vii

10 Lewis WR. Echocardiography in the evaluation of patients in chest pain units. Cardiol Clin. 2005;23:531–539. vii

11 Tong KL, Kaul S, Wang XQ, et al. Myocardial contrast echocardiography versus Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction score in patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain and a nondiagnostic electrocardiogram. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:920–927.

12 Labovitz AJ, Noble VE, Bierig M, et al. Focused cardiac ultrasound in the emergent setting: a consensus statement of the American Society of Echocardiography and American College of Emergency Physicians. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:1225–1230.

13 Bholasingh R, Cornel JH, Kamp O, et al. Prognostic value of predischarge dobutamine stress echocardiography in chest pain patients with a negative cardiac troponin T. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:596–602.

14 Geleijnse ML, Elhendy A, Kasprzak JD, et al. Safety and prognostic value of early dobutamine-atropine stress echocardiography in patients with spontaneous chest pain and a non-diagnostic electrocardiogram. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:397–406.

15 Nucifora G, Badano LP, Sarraf-Zadegan N, et al. Comparison of early dobutamine stress echocardiography and exercise electrocardiographic testing for management of patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:1068–1073.

16 Varetto T, Cantalupi D, Altieri A, et al. Emergency room technetium-99m sestamibi imaging to rule out acute myocardial ischemic events in patients with nondiagnostic electrocardiograms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:1804–1808.

17 Kontos MC, Jesse RL, Anderson FP, et al. Comparison of myocardial perfusion imaging and cardiac troponin I in patients admitted to the emergency department with chest pain. Circulation. 1999;99:2073–2078.

18 Hilton TC, Fulmer H, Abuan T, et al. Ninety-day follow-up of patients in the emergency department with chest pain who undergo initial single-photon emission computed tomographic perfusion scintigraphy with technetium 99m–labeled sestamibi. J Nucl Cardiol. 1996;3:308–311.

19 Gallagher MJ, Raff GL. Use of multislice CT for the evaluation of emergency room patients with chest pain: the so-called “triple rule-out.”. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;71:92–99.

20 Hollander JE, Chang AM, Shofer FS, et al. One-year outcomes following coronary computerized tomographic angiography for evaluation of emergency department patients with potential acute coronary syndrome. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:693–698.

21 McCord J, Amsterdam EA. Newer imaging methods for triaging patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain. Cardiol Clin. 2005;23:541–548. vii–viii

22 Hoffmann U. Diagnostic value of comprehensive cardiothoracic dual source CT for the early triage of patients with undifferentiated acute chest pain. Massachusetts General Hospital Bracco Diagnostics, Inc; ongoing trial 2010. Accessed February 23, 2011. Available at www.clinicaltrials.gov

23 Kwong RY, Schussheim AE, Rekhraj S, et al. Detecting acute coronary syndrome in the emergency department with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2003;107:531–537.

24 Fayad ZA. MR imaging for the noninvasive assessment of atherothrombotic plaques. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2003;11:101–113.

25 Soman P, Bokor D, Lahiri A. Why cardiac magnetic resonance imaging will not make it. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23(Suppl 1):S143–S149.