48 Cancer of the Uterine Cervix

Epidemiology

It was estimated that 11,270 new cases of invasive carcinoma of the uterine cervix would be diagnosed in the United States in 2009, representing 1.6% of all cancers in women.1 An estimated 4070 deaths from cervical cancer were expected in 2008, accounting for 1.5% of all cancer deaths in women. The average age for patients with invasive disease is in the mid- to late 40s, with approximately 25% of cases and 50% of deaths occurring in patients older than 65. At the time of presentation, 45% of cases are localized, 34% have regional spread, and 10% have disseminated disease.

During the last five decades, the incidence of invasive cervical carcinoma has dropped dramatically, from 32.6 (late 1940s) to 8.3 (mid-1980s) per 100,000 women in the United States.2 Much of this improvement is attributable to the development of effective screening techniques for the identification of preinvasive lesions. Incidence varies worldwide, with the highest rates found in Latin America and the lowest prevalence found among Jewish women in Israel. Over the past decade, there has been a noticeable increase in the incidence of preinvasive lesions reported in many nations, and an actual increase in mortality rates in young women in Canada, Great Britain, New Zealand, and Australia.2

Lower socioeconomic status is associated with an increased risk of frankly invasive disease, partially because of ineffective or absent screening programs in many parts of the world.3 Although in developed nations there appears to be an increased incidence among black and Latino people as compared with white or Asian people Surveillance Epidemiology End Results (SEER) data from 1987 showed that black people had twice the incidence of invasive cervical cancer as white people, socioeconomic factors cloud the issue.2 When evaluated in a multifactorial analysis, race drops significantly as a major factor.

As of January 1, 1993, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention modified their reporting guidelines to state that the presence of cervical carcinoma in the setting of infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) establishes the diagnosis of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), regardless of CD4 count or absence of prior opportunistic infections. The incidence of infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) is higher in HIV-positive women than their HIV-negative counterparts. Likewise, because T-cell immunity is essential in maintaining control of HPV infection, an increase in the incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and invasive cervical carcinoma is seen in this population.4

Two strains of HPV (16 and 18) are considered to have a high malignant potential, whereas strains 31, 33, 35, 39, 40, 45, 51-56, and 58 have a moderate malignant potential. HPV DNA sequences are identified in 80% to 100% of cervical carcinomas evaluated by polymerase chain reaction.4 In June 2006, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first preventive HPV vaccine (quadrivalent HPV recombinant vaccine [Gardasil]). In 2007, the FDA approved a second HPV vaccine (HPV bivalent vaccine [Cervarix]). In a 5455-patient, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial, the vaccine showed 100% efficacy against cervical lesions and external anogenital and vaginal lesion in the patients who completed the vaccination regimen.5 The adverse events associated with the vaccine were mild to moderate. Serious adverse events occurred in less than 0.1% of patients. The vaccine is currently not licensed to use in female patients younger than 9 years or older than 26 years, or for male patients. Proposals for compulsory vaccination are currently being evaluated in various states.

Attention has returned to the role of herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV2) as a potential cofactor with HPV in the initiation of malignant degeneration.2 Women with HSV2 alone have a 1.2 relative risk (RR) compared with women negative for both HPV and HSV2. Those positive for HPV16/18 DNA alone had an RR of 4.3, but those positive for HPV 16/18 and HSV2 had an RR of 8.8.

Early age at initiation of sexual activity and multiple sexual partners are associated with increased risk.2 Girls who begin engaging in intercourse before the age of 16 have a twofold increase in risk over those who begin after age 20. Exceptionally low rates are found in Catholic nuns and Mormon and Amish women. Cigarette smoking has been implicated,2 with most studies revealing a twofold increase in incidence in smokers compared with nonsmokers. Multiple dietary elements are currently being investigated for their potentially protective effects, including vitamins A, C, and E, as well as beta-carotene.

Diethylstilbestrol (DES), a nonsteroidal estrogen developed in the 1940s and used in the prevention of recurrent or threatened miscarriages, was administered to between 0.5 and 2 million women in the United States before it was banned for this purpose by the FDA in 1971. Intrauterine exposure to DES was found to be associated with the development of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the cervix and vagina.6,7 In reports from the Registry for Research on Hormonal Transplacental Carcinogenesis, 60% of 519 cases of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina or cervix were found to be related to exposure to DES or related compounds, with an estimated risk after exposure of 1 in 1000 up to the age of 34.8 Ninety-one percent of patients were diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 27, with more than 90% presenting with early (stage I or II) disease.

Anatomy

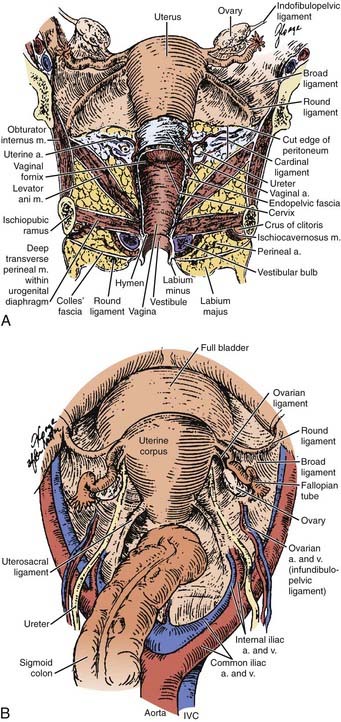

A clear understanding of the anatomic relationships of the uterine cervix and surrounding structures is essential for maximizing the therapeutic ratio in the management of cervical carcinoma. The cervix is sandwiched between the trigone of the bladder, the ureters, the anterior wall of the rectum, and the sigmoid colon, so that these critical organs are by necessity exposed to the interventions used to control neoplasms of the cervix (Fig. 48-1). The uterus itself is a hollow muscular organ divided functionally into two parts, the fundus and cervix, separated by a constriction known as the isthmus. The upper portion, the body or corpus uteri, is covered by the reflection of the peritoneum, which anteriorly becomes the peritoneal reflection over the bladder and posteriorly extends down over the cervix and posterior fornix of the vagina before covering the anterior portion of the rectum and sigmoid colon. The broad ligament is a double layer of peritoneum through which the blood supply, lymphatics, and nerves of the uterus course. These ligaments connect the lateral aspects of the uterus with the pelvic side walls. They contain three ligaments: (1) the round ligament anteriorly, which courses out through the abdominal inguinal ring; (2) the ovarian ligament posteriorly connecting the uterine pole of the ovary and the lateral uterus; and (3) the suspensory ligament of the ovary between the two layers of the broad ligament connecting the lateral pole of the ovary and the pelvic side wall. Atop the broad ligament lie the fallopian tubes. The ovaries are located posteriorly.

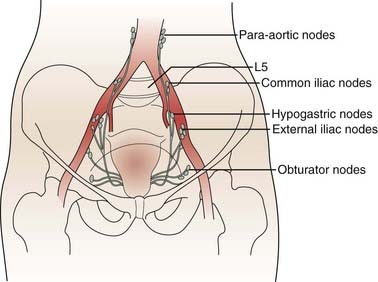

The lymphatics of the cervix course in three separate routes (Fig. 48-2). Laterally, they pass along the uterine artery to the external iliac lymph nodes. Posterolaterally, they pass behind the ureters to the internal iliac nodes. Posteriorly, they enter the common iliac and lateral sacral nodal groups. The fundus of the uterus drains mainly to the internal iliac nodes via lymphatics in the broad ligament, although some drainage occurs to the para-aortic chain via the ovarian vessels, to the external iliac chain, and to the inguinal nodes via the round ligament. The upper vagina drains laterally to both the internal and external iliac nodal groups, whereas the middle third tends to drain to the internal iliac group alone. The lower third of the vagina has lymphatic channels that merge with those of the vulva and lead to the superficial inguinal region. Depending on the local growth characteristics of cervical tumors, therefore, involvement of the internal and external iliac, para-aortic, sacral, and inguinal nodes is possible and must be taken into consideration when a treatment strategy is planned.

Pathologic Conditions

In 1988, the National Cancer Institute convened a workshop to develop modern guidelines for cytopathologic reporting of cervical and vaginal specimens to replace the outdated Papanicolaou (Pap) classification, resulting in the Bethesda classification system for cytopathology reports (Table 48-1).9 For those lesions considered to be possible precursors of invasive carcinoma, the previously used CIN (levels I, II, III) and dysplasia (mild, moderate, severe, carcinoma in situ [CIS]) grading systems were replaced with a two-tier designation. Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LGSILs) include those lesions previously referred to as cellular changes associated with HPV infection or mild dysplasia (CIN I). High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HGSILs) include moderate or severe dysplasia (CIN II or III) or CIS.

Table 48-1 Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical/Vaginal Cytologic Diagnoses

CIN, Cervical intraepithelial neoplasm; HGSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; HPV, human papillomavirus; LGSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; SIL, squamous intraepithelial lesions; WNL, within normal limits.

From NCI Workshop: The 1988 Bethesda system for reporting cervical/vaginal cytologic diagnoses, JAMA 262:931, 1989.

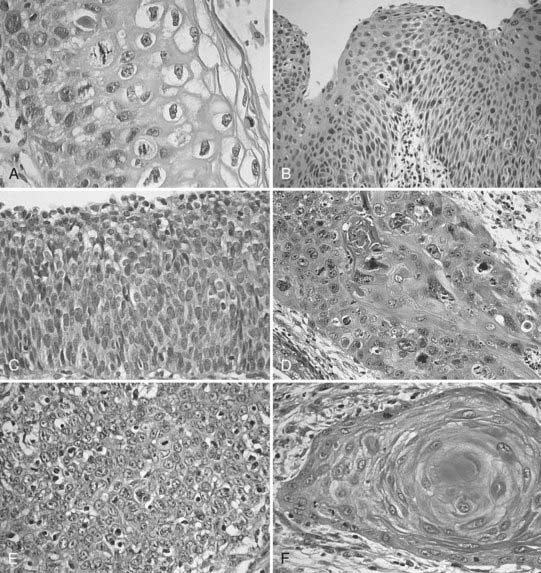

Invasive cervical cancers comprise approximately 85% squamous cell varieties, 15% adenocarcinomas, and a rare collection of other entities. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) has been classified according to a new system by the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists to include keratinizing, nonkeratinizing, verrucous, papillary transitional, and lymphoepithelial types (Table 48-2).10 Adenocarcinomas include the following subtypes: mucinous (endocervical, intestinal, and signet ring types), endometrioid, clear cell, minimal deviation (adenoma malignum), papillary villoglandular, serous, and mesonephric. The remaining tumor types include adenosquamous, glassy cell, adenoid cystic, adenoid basal, carcinoid, small cell, and undifferentiated carcinomas (Fig. 48-3).

Table 48-2 Histopathologic Type

From American Joint Committee on Cancer: Cervix uteri. In Fleming ID, Cooper JS, Henson DE, et al, (eds): AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2002, Lippincott-Raven.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Several different classification systems have been suggested during the past 60 years, including the early Broders/Warren classification (based on differentiation, mitotic activity, keratinization, and pearl formation) and that of Reagan and Ng (based on size, keratinization, and nuclear pleomorphism).11 In an analysis of patients entered into the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) prospective treatment protocol for stage IB cervix carcinoma, none of the histologic grading systems for SCCs were found to correlate with incidence of lymph node metastasis or progression-free interval.12

Variants of SCC of the cervix exist, although it is unclear that any of these variations affect response to therapy. Verrucous carcinoma is a very well-differentiated carcinoma lacking cellular atypia and possessing orderly elements of maturation. It can achieve massive exophytic proportions and be extensively invasive, in contrast to the bland microscopic appearance. Verrucous carcinomas are differentiated from condylomata by the presence of invasion in addition to a lack of fibrovascular cores in the papillae, as well as by the exophytic expansion of surrounding normal tissue.11,13 Spread to lymph nodes is quite rare. Concern is expressed by many authors that the use of radiation in these lesions may contribute to malignant degeneration, but this point is contestable.14

Papillary squamous cell differs from the verrucous form in that its cells show a high degree of nuclear atypia. Although grossly the tumor may have a warty, exophytic appearance, on microscopic examination there are found papillae with atypical immature basaloid cells reminiscent of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. The determination of invasion requires full-thickness biopsy, because a large exophytic component may be associated with a minimal amount of invasion.11

Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinomas account for 10% to 20% of cervical neoplasms in the literature.15 This appears to represent an increase from older data that showed the incidence to be in the range of 5% to 10%, possibly because of a decline in the incidence in invasive SCC secondary to effective screening programs, although the possibility remains that the incidence of adenocarcinoma is actually on the rise. The most common type, endocervical adenocarcinoma, generally is composed of mucin-producing glands of varying differentiation, within a fibrous stroma that sets it apart from normal endometrial stroma. It may be difficult to differentiate from adenocarcinoma of uterine corpus origin, increasing the necessity of a proper fractional dilatation and curettage (D&C) to establish the actual origin of the disease. It appears in an admixture with other variants in a frequent number of cases.

Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma is a variant that is an extremely well-differentiated lesion composed of endocervical glands with basal nuclei and low nuclear/cytoplasmic ratios.16,17 The nuclei appear minimally atypical, belying the aggressive clinical nature. On extensive sampling, markedly dysplastic cells can be identified. These malignant glands can be helpful in differentiating these lesions from other benign conditions such as adenomatous hyperplasia or deep nabothian cysts. They are almost uniformly deeply invasive and are associated with a very poor prognosis. A high frequency of associated mucinous tumors of the ovary has also been reported.

Villoglandular papillary adenocarcinoma is generally found in younger women (average age 33) and consists of a surface papillary component with fibrous stroma.17 Unless there is clear evidence of vascular involvement or deep invasion, conservative management may be warranted owing to the excellent prognosis.

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the cervix is difficult to distinguish histologically from uterine adenocarcinoma. The clinical activity is similar to the endocervical variety.15,18

Clear cell adenocarcinomas of the cervix, most commonly seen in young women exposed to DES in utero, are identical to the lesions that show up in the vagina, endometrium, and ovary. They can be seen in women of any age in the absence of DES exposure history. Three patterns have been described (tubulocystic, solid, and papillary), with the appearance of cells bearing a “hobnail” configuration that clearly sets them apart from other variants of adenocarcinoma.6,8,19

Serous papillary adenocarcinoma is a rare subtype, which histologically looks similar to its namesake in the uterus and ovary.20 A search must be carried out to ensure that it is not a metastatic deposit from another site in the pelvis. Too few cases have been reported to state whether or not this entity in the cervix is prone to intraperitoneal dissemination like the uterine variety. Mesonephric, signet ring cell, and intestinal-type adenocarcinomas are additional extremely rare subtypes, for which care must be taken to rule out metastases from other locations.15

Adenosquamous and Glassy Cell Carcinoma

Adenosquamous carcinomas are tumors that contain mucin or glands in an admixture with clearly recognizable squamous elements.15,21 Any pattern of squamous cell may appear in this setting, usually in conjunction with poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. Once again, care should be taken to establish that this is truly adenosquamous carcinoma and not two separate primary tumors of the cervix and corpus (“collision” tumors). A particularly aggressive form of poorly differentiated adenosquamous carcinoma is the glassy cell carcinoma, so called because of a ground-glass appearance to the finely granulated cytoplasm in conjunction with clearly defined cell walls and large nuclei with prominent nucleoli.21,22 These tumors, representing approximately 1% to 2% of all cervical neoplasms, have a high mitotic rate and a particularly aggressive course.

Small Cell (Neuroendocrine) Carcinoma

Small cell carcinoma is a neuroendocrine tumor similar to small cell tumors of the lung, believed to arise from amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation cells.23 It accounts for less than 2% of all cervical neoplasms. These lesions may have been lumped in with other small cell variants of squamous cell in the classification of Reagan mentioned earlier, giving rise to the differences seen in clinical outcome using that schema. Histologically, however, the picture seen is a sea of small monomorphous cells with a high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, with an occasional minimal element of glandular or squamous differentiation. Neuroendocrine granules may be identified on electron microscopy or immunohistochemical analysis. Up to one half may stain for markers such as serotonin, adrenocorticotrophic hormone, somatostatin, or gastrin, although clinical syndromes associated with the production of these markers is very unusual. A hallmark of this disease is its systemic nature early in the course of the disease. Any meaningful intervention must take into account the high propensity for early dissemination and include chemotherapeutic approaches similar to those used for oat cell carcinoma of the lung.

Other rare cervical tumors include carcinoid, adenoid basal, adenoid cystic, sarcomas (mixed müllerian, endocervical stromal), embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, and melanoma. The interested reader is referred to the excellent review article by Clement.24 Although uncommon, the cervix may also be a site of metastatic disease.

Clinical Presentation

Extensive data support the theory that malignant lesions arise from the precursor lesions described as HGSIL. On reviews of earlier biopsies of patients found to have invasive disease, severe dysplasia and CIS are often found. Similarly, patients followed with serial biopsies after discovery of HGSIL show subsequent development of frank invasion. The two lesions are often found concurrently in specimens, and both arise most frequently from the squamocolumnar junction or the transformation zone.25 Most significantly, however, incident rates and death rates resulting from invasive cancer of the cervix have dropped dramatically during the past years in those regions where effective detection and treatment of HGSIL occurred.

Once the disease has broken through the basement membrane, the possibility of metastatic spread exists. Carcinoma of the cervix is divided into microinvasive (minimally invasive) or invasive. The former, making up approximately 10% of all carcinomas of the cervix, is defined as any tumor with no evidence of vascular or lymphatic invasion and less than or equal to 3 mm deepest invasion below the superficial stromal-epithelial interface. The depth of invasion necessary to satisfy the criteria for this diagnosis has been the subject of considerable controversy, varying from 1 to 5 mm, with most authors preferring the 3 mm mark, because lesions with this degree of invasion have less than 1% risk of lymph node metastases. In cases with invasion from 3.1 to 5 mm, 12 of 146 patients (8%) had pelvic lymph node metastases at lymphadenectomy.26 Although technically not a part of the definition of microinvasive carcinoma, the extent of lateral spread of the tumor has considerable prognostic significance, with lesions greater than 7 mm being associated with a greater lymph node metastatic rate.27

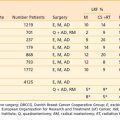

Dissemination of disease occurs either mainly through lymphatic channels or hematogenously, although intraperitoneal spread may occur in advanced disease. The lymphatic spread of disease tends to be orderly and predictable with internal and external iliac nodes first involved, followed by common iliac and para-aortic spread. Involvement of the lower third of the vagina is associated with spread to the inguinofemoral lymph nodes. The incidence of nodal involvement is correlated significantly with the stage and volume of local disease, as well as depth of invasion (Table 48-3).28 Stage I disease has an 11% to 18% risk of pelvic nodal involvement; stage II, 32% to 45%; and stage III, 46% to 66%.28 Para-aortic nodal involvement can also be associated with early stage disease and has been found to be a powerful prognosticator. The incidence of para-aortic nodal involvement is 0% to 18% for stage IB/IIA disease, 13% to 33% for stage IIB, up to 46% for stage III disease, and as high as 57% for stage IVA disease.29–31

| Stage | I | 11%-18% |

| II | 32%-45% | |

| III | 46%-66% | |

| Depth of invasion | ≤3 mm | <1% |

| 3-5 mm | 1%-8% | |

| ≤5 mm | <1%-3.5% | |

| 6-10 mm | 15.1% | |

| 11-15 mm | 22.2% | |

| 16-20 mm | 38.8% | |

| >20 mm | 22.6% | |

| Maximum tumor dimension (IB/II) | 0.1-1.0 cm | 12.7% |

| 15.8 cm | 1.1%-2.0% | |

| 2.1-3.0 cm | 16.3% | |

| ≤3 cm | 21% | |

| >3 cm | 23%-42% | |

| Grade | 1 | 9.7% |

| 2 | 13.9% | |

| 3 | 21.8% | |

| Lymphovascular space invasion | Absent | 8.2% |

| Present | 25.4% |

Prognostic Factors

Tumor volume is directly related to the incidence of spread to pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes, as well as inversely related to local control and actuarial survival. In a retrospective review by Piver and Chung30 of 289 patients who underwent a radical hysterectomy for stages IB, IIA, or recurrent cervical carcinoma at Roswell Park, patients with tumors 3 cm or less had a 21% incidence of pathologically involved nodes, compared with 35% to 42% for those patients with tumors greater than 3 cm. In a prospective GOG surgical pathologic study of patients with stage I SCC of the cervix treated with a radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection, tumors up to 1.0 cm in maximum diameter had a 12% incidence of involved pelvic lymph nodes, compared with 23% for those tumors greater than 3 cm.32 A separate analysis of patients entered into three consecutive radiation trials for stage I-IVA cervical cancer by the GOG found tumor size to be a significant predictor for progression-free interval.33

In a retrospective review of 625 patients with stage IB-IIB cervical cancer treated with a radical hysterectomy between 1965 and 1977, Inoue28 found a significant correlation between the depth of invasion and the incidence of pelvic nodal involvement and parametrial involvement. Of 97 tumors less than 5 mm deep, there was only one with pathologic evidence of involvement of pelvic nodes. Other investigators have reported that tumors measuring less than 3 mm in maximum depth have a less than 1% risk of spread to pelvic lymph nodes,26 whereas tumors in the range of 3 to 5 mm deep have up to an 8% incidence of nodal involvement.34 Depth of invasion was a potent prognosticator for spread to pelvic lymph nodes in the GOG surgical pathologic study of patients with stage I cancer (P < 0.0001).32

Despite its imperfections, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system has been effective in dividing patients into groups with different prognoses. The FIGO report of 8538 patients treated with either radiation or surgery between 1982 and 1986 showed the following 5-year actuarial survival rates: stage I, 81.6%; stage II, 61.5%; stage III, 36.7%; stage IV, 12.1%.35 According to the Patterns of Care Study, 5-year survival rates for stages I, II, and III cancers of the cervix treated with radiation were 74%, 56%, and 33%, respectively.36 The French Cooperative Group report in 1988 stated survival rates of 89% for patients with stage IB disease, 85% for IIA, 76% for IIB, 62% for IIIA, 50% for IIIB, and 20% for stage IV.37

Metastatic disease in the pelvic nodes is a powerful prognostic factor, as evidenced by multivariate analyses in both retrospective and prospective reports. The presence of disease in pelvic lymph nodes in stage I disease decreases the survival into the 50% to 60% range.28,30,38,39 In the Annual Report of the FIGO results in cervical cancer, patients with stage IB disease with negative nodes had an 89.5% 5-year survival versus 59% for those with histologically positive nodal involvement.35 In a retrospective review of 875 patients with stage IB-IIB resected cases found survival rates of 89%, 81%, 63%, and 41% for patients with no nodes, 1 node, 2 to 3 nodes, and 4 to 18 nodes positive, respectively.38 In the GOG analysis of patients treated with definitive radiation, the presence of para-aortic adenopathy was found to be the most potent prognostic factor evaluated.40

Anemia has been associated with decreased local control in patients with locally advanced cervical carcinoma in many series.41,42 The issue is quite complex because of the varying level of hemoglobin used to define anemia and the association of anemia with more advanced disease at presentation.43 In a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in a retrospective review of 2800 patients with cervical carcinoma of all stages treated for cure performed at Princess Margaret Hospital, Bush found that anemia achieved a high level of significance, particularly at levels below 12 g/dl.44 It is not clear, however, that performing transfusions on patients to bring them up to a hemoglobin level of 12 g/dl alters outcome. In prospective study from the Princess Margaret Hospital, 132 patients with stage IIB or III disease were initially randomly assigned to either receive transfusions to keep their hemoglobin above 12.5 or not receive transfusions until the hemoglobin fell below 10 g/dl.44 Patients in either arm with hemoglobin greater than 12.5 did not receive transfusions. A subgroup analysis done retrospectively showed a significant decrease in local failure and disease-specific death rates for patients who received transfusions to keep their hemoglobin above 12 compared with anemic patients who did not receive transfusions. This information, although suggestive of a benefit for transfusion, is not conclusive. Several authors have failed to find a correlation between anemia and response to radiation. The suggested benefit of correction of the anemia must be weighed against the attendant risks of routine transfusions.41 Prior to the initiation of radiation, it is reasonable to correct severe anemia (hemoglobin less than 10 g/dl), or to transfuse the patient with borderline anemia who continues to actively bleed while attempts are made to control the bleeding with packing, the use of Monsel ferric subsulfate solution, and radiation intervention. Given the prognostic significance of anemia during radiation, it is hypothesized that by raising and maintaining hemoglobin level above 12 g/dl using erythropoietin may decrease secondary hypoxia and improve survival. GOG performed a prospective randomized trial comparing maintenance of a hemoglobin level at or above 12 g/dl with recombinant human erythropoietin or maintenance of a hemoglobin level at or above 10 g/dl with transfusion.45 Of eligible patients, 109 were randomized to the two arms of the trial. The trial was closed prematurely because of potential concerns for thromboembolic events (TEs).46 The rate of TEs was 4 of 52 in the chemoradiotherapy arm versus 11 of 57 in the erythropoietin arm. However, the difference in rate of TEs was not significantly different.

The questionable influence of endometrial extension on outcome is inter-related with the volume of tumor as well as the issue of parametrial extension (stage). Several retrospective reports identify endometrial stromal invasion as having a negative affect on survival, possibly because of an increase in distant metastases rather than an increased incidence of local failure after definitive irradiation.47,48

Young age at diagnosis appears to carry with it a worse prognosis.40,42,49–51 Karnofsky performance status has been identified as an independent prognostic factor of actuarial survival in the GOG analysis of 606 patients entered into three consecutive radiation therapy trials.52

Women with cervical cancer and HIV tend to present with more advanced disease compared with seronegative patients.53,54 In a report of 84 patients evaluated and treated for cervical cancer at the State University of New York, 16 patients were known to be HIV-positive. Only one of these patients presented with early stage disease, compared with 40% of the remaining 68 HIV-negative women. Of the 16, 10 suffered recurrences after a brief interval, 4 were either lost to follow-up or died shortly after therapy, and only 2 experienced long-term control. The mean CD4 count, a crude indicator of the immune status of the patient, was 360 compared with 830 for the HIV-negative group. The only two long-term survivors were patients with initial CD4 counts greater than 600. HIV status, taken in conjunction with other measures of the immunocompetence of the patient (such as frequency of opportunistic infections, CD4 count) has a profound influence on tolerance to therapy and overall survival.53

Staging and Workup

Diagnostic Workup and Staging

The current FIGO staging system has evolved during the past 60 years from its initial formation in 1929 as the League of Nations Health Organization system (Table 48-4). Various changes have been made during that interval to incorporate applicable information, such as the removal of corpus extension from staging consideration (1950) and the creation of stage IA in 1962 and its later subdivision into IA1 and IA2 (1972), and IB1 and IB2 (1998). In the current system, Stage IIA is further subdivided into stage IIA1 and IIA2 (2010).

Table 48-4 Classification of Uterine Cervix Cancer

Rights were not granted to include this table in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book.

The 5-year survival rate for patients with stage IB disease can vary from less than 20% for patients with bulky disease and both pelvic and para-aortic adenopathy to greater than 90% for those with lesions less than 2 cm in maximum diameter and no involved nodes.55 Survival rates for patients with higher staged disease also vary within each stage depending on primary tumor volume and nodal status.37,56 In the Patterns of Care report on the uterine cervix, the differentiation between IA and IB was not found to predict for either 5-year actuarial survival or pelvic control, whereas the presence of bulky disease did correlate with a higher pelvic failure rate in stage IB disease.56 In stage II disease, unilateral versus bilateral disease significantly affected both actuarial survival and pelvic control rates, a significance that persisted on multivariate analysis. In the analysis of stage III disease, the differentiation between unilateral or bilateral sidewall or lower-third vaginal involvement was highly significant in both actuarial survival and pelvic control results. The GOG findings regarding the great prognostic significance of para-aortic adenopathy and tumor volume also point out the shortcomings of the current system.40

The American Joint Committee on Cancer has devised a tumor-node-metastasis system similar to the FIGO system. The FIGO staging system is most widely used (see Table 48-4), despite its shortcomings. For practical purposes of reporting, it is imperative that the clinical staging rules be adhered to in order to ensure accurate comparisons of therapeutic interventions. The rules for clinical staging according to FIGO state that staging is to be based on careful clinical examination prior to intervention, preferably an examination under anesthesia. Once established, the stage is not to be changed by later findings or therapeutic interventions. Palpation, inspection, colposcopy, endocervical curettage, hysteroscopy, cystoscopy, proctoscopy, intravenous urography, and x-ray examination of the lungs and skeleton are recommended. Suspected involvement of the bladder or rectum must be documented by histology. Specifically excluded from the clinical staging system are the results of such tests as lymphangiography, fine-needle aspiration or biopsy of lymph node, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), laparoscopy, and laparotomy. These tests are not allowed to influence the clinical stage for reporting purposes but may be used for treatment planning and providing important diagnostic information.

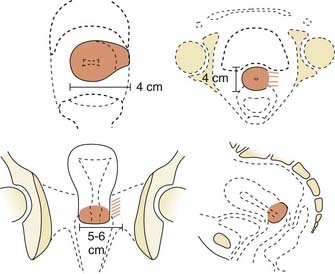

Locally, it is important to fully describe the extent of palpable disease through the use of extensive diagrams and descriptions of the three-dimensional (3-D) characteristics of the lesion (Fig. 48-4). The degree of parametrial (medial or lateral, unilateral or bilateral) or vaginal (upper two-thirds, lower one-third) extension should be clearly defined, as should the presence or absence of hydronephrosis, rectal invasion, bladder mucosal invasion, bullous edema, uterosacral ligament involvement, or extension to the pelvic sidewall (bilateral or unilateral). The use of MRI evaluation of the pelvis is not allowed by the current staging system in determining the clinical stage but has proven to be of benefit in defining the extent of disease locally as well as regionally. It also provides information that is useful in optimizing brachytherapy planning. Cystoscopy and proctosigmoidoscopy are routinely called for by the FIGO system, but in cases of early disease in which MRI shows no suspicion of local extension, these more invasive procedures may not be necessary. On the other hand, if an MRI scan raises the question of bladder or rectal involvement, endoscopic evaluation is essential to rule out pathologic involvement of these organs. A CT scan with contrast can provide information as to the presence of hydroureterosis or hydronephrosis.

Positron emission tomography (PET) has become a useful staging modality for locally advance cervical cancer. It may be an accurate noninvasive method of evaluating nodal status, endometrial extension, tumor volume, and prognosis.57–60 PET scan also may play an important role in post-therapy monitoring. Grigsby and associates showed that patients treated with radiotherapy who had a normal 3-month post therapy PET scan had a 5-year cause-specific survival of 80%.61 Another study shows PET scans as an effective way of detecting asymptomatic recurrence.62

Further routine workup should include a complete blood count, liver function tests, renal function tests, and a chest x-ray. In patients believed to be at risk for exposure to HIV, testing for antibodies to HIV should be discussed with the patient prior to the initiation of therapy. If the patient is HIV antibody–positive, the CD4 count is currently recommended as a rough indicator of the immune status and of the patient’s likelihood to be able to tolerate therapy.53 The usefulness of a bone scan is limited to patients with advanced disease with symptoms suggestive of dissemination and is not routinely obtained. In cases in which there is evidence of spread to pelvic lymph nodes on pelvic CT or MRI scan, evaluation of the abdomen to rule out higher adenopathy or liver involvement is recommended.

Blind scalene node biopsy performed in the setting of positive para-aortic lymphadenopathy has a positive rate of 0% to 35%.63 In a prospective evaluation of biopsies of nonpalpable scalene nodes in 55 patients with positive para-aortic (48) or high common iliac nodes (8), only 4 were confirmed positive (14%).64 The routine use of such biopsies is not warranted. Prior to the initiation of para-aortic radiation for patients with known retroperitoneal disease, CT scan of the chest to rule out disease missed on plain chest x-rays may be a more useful test than biopsy of clinically negative nodes.

Management Newly Diagnosed Cervical Cancer

Carcinoma In Situ and Stage IA Disease

CIS and disease with early stromal invasion isolated to buds of neoplastic cells that penetrate the basement membrane but remain immeasurable macroscopically (stage IA) have essentially a 0% incidence of involvement of the lymph nodes.65–67 In the absence of disease at the cone biopsy margins, a recurrence rate of 0% would be expected after simple hysterectomy. Conization itself represents adequate therapy in these cases, as long as the margins are definitely clear. A lesion cannot be classified as stage IA disease unless all margins of the cone biopsy are free of disease, because the entirety of the lesion may not have been identified. Alternative approaches such as laser vaporization and cryotherapy have success rates in excess of 95%, although obliteration of the margins may make it difficult to identify those patients with residual disease.65,68

The presence of LVSI or invasion to a depth greater than 3 mm is associated with a slight increase in the risk of spread to pelvic nodes or recurrence after hysterectomy. Up to 13% of patients with these findings may have lymphatic spread at time of hysterectomy (range 2%-13%),66,67 arguing for more aggressive local therapy tailored to the histologic findings. Patients with LVSI but invasion to less than 3 mm and clear margins after cone-down application might be suitable for a simple hysterectomy and pelvic node dissection to reduce morbidity. If, however, the depth of invasion is from 3.1 to 5 mm and LVSI is present, an extended or radical hysterectomy should be performed. Under these conditions, if the patient strongly desires to maintain her ability to bear children, a therapeutic conization may be considered, but close follow-up is essential as invasive recurrences are reported in up to 5% of cases.66,67

Surgical approaches are preferred for such minimal disease. In cases of medical inoperability, definitive radiation is an acceptable alternative with outstanding results.67,69 Multiple intracavitary insertions are employed to deliver a dose of 60 to 70 Gy to the cervix. External-beam radiation is not routinely employed for stage IA disease, unless the risk of pelvic nodal spread is considered to be substantial, such as in a case with greater than 3-mm invasion, LVSI, and poorly differentiated histologic findings.

Surgery alone for stage IA disease has resulted in local recurrence rates of 2% to 5%, with the majority of recurrences being noninvasive and amenable to effective salvage. Kolstad, reporting on 496 cases of microinvasive disease treated with surgery in Norway, had recurrences in only 15 patients, all of whom were cured with further surgery.67 In a review by Sevin and coworkers of six major series in the literature, 0.2% of 513 cases with disease invasion less than 3 mm recurred, versus 5.4% of 166 cases with invasion of 3.1 to 5.0 mm.66

The results with radiation alone are comparable to those found with surgery. In Kolstad’s series, an additional 136 patients were treated with brachytherapy alone, and none had recurrences. Of 32 patients with IA disease treated at Mallinkrodt with radiation alone (either with brachytherapy alone or in combination with external-beam therapy), there was only one failure reported at 15 years.69

Stage IA2/IB1/IIA (≤4 cm) (Surgical Candidates)

Stage IB1/IIA lesions that measure 4 cm or less can be managed with either definitive surgery or radiation. The decision usually hinges on the side effects and complications associated with each procedure and the medical condition of the patient. The standard surgical approach is the radical hysterectomy with pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection. Five-year disease-free survival rates of 80% to 92%70,71 are reported after radical hysterectomy, whereas for radiation, the actuarial 5-year survival rates vary from 78% to 90%.72–74

With that prelude, the retrospective reports reveal a notable similarity in results for radiation and surgery. Reporting on 978 consecutive patients with early stage disease who underwent radical hysterectomy between 1965 and 1990 at the University of Miami, Averette and colleagues75 had a 90.1% 5-year actuarial survival overall, 90.5% for stage IB, and 65.7% for stage IIA. Breaking them down by histologic characteristics, SCC had a 90.7% 5-year survival, adenocarcinoma 80.5%, and adenosquamous carcinoma 63.5%. Of the 17.7% of patients who had positive pelvic lymph nodes, the 5-year survival was 63.5%, and 40.8% for those with positive para-aortic lymph nodes.75 Overall complications in this series were as follows: 0.8% urinary fistulae, 8.5% wound-related problems, 20.5% bladder dysfunction, 6% ileus, and 2.6% chronic lymphedema.

Radiation results in reports on 5-year survival rates of patients with clinical stage IB range from 80% to 85% range for most modern series.37,73,74,76 Stage IIA results range from 70% to 76%.37,73,74 Considering the previous statements about treatment selection bias, these results compare quite favorably with those seen with surgery. Central disease control rates of 92% to 94% are reported for patients with stage IB cervical cancers treated with radiation alone.37,76

The only prospective randomized trial between surgery and radiotherapy was reported by Landoni et al. in 1997.77 During a period of 5 years, 343 patients with stage IB and IIA cervical carcinoma were randomized between surgery and radiotherapy. Adjuvant radiotherapy was given for patients found to have pathologic T2b or greater lesions with margins smaller than 3 mm, cut-through, or positive lymph nodes. The result were analyzed based on intention to treat. With a median follow-up of 87 months, the 5-year overall and disease-free survival were identical between the two groups. Of the surgery group, 28% had severe morbidity compared with 12% of patients in the radiotherapy group (P = 0.0004). Patients who received combined surgery and radiotherapy had the worst morbidity. The result of this study suggests only patients with limited disease that can be completely excised may be offered the option of surgery.

Stage IB/IIA(>4 cm), Bulky Lesions (Not Surgical Candidates)

Based on prior small randomized studies of patients with stages IIB-IIIB cervical carcinoma treated at Roswell Park looking at the addition of hydroxyurea, the GOG initiated a group-wide phase III study of patients with stage IIIB-IVA disease (surgically staged and negative para-aortic nodes), randomly assigning patients to receive radiation therapy alone or radiation plus hydroxyurea.78 Results of this study (the analysis pertained to only 97 of the original 190 patients entered; approximately half of the patients were considered inevaluable) showed a marginal improvement in complete clinical response and superiority in disease-free survival and overall survival rates in those receiving hydroxyurea. Significant toxicity was seen in the hydroxyurea arm (47%).

The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) randomly assigned patients with stage IIIB-IVA disease to receive radiation therapy with or without misonidazole, a radiation sensitizer, and found that misonidazole may have had a deleterious effect on overall survival compared with radiation therapy alone.79 The median survival in the control arm was 1.9 years, compared with 1.6 years for the misonidazole arm, and the study was terminated early. A GOG study randomly assigned patients with stage IIB-IVA disease to receive radiation therapy plus hydroxyurea or misonidazole from 1981 to 1985.52 No difference was observed between the two arms in terms of progression-free survival or overall survival rates, although there was a trend favoring the hydroxyurea arm. Their conclusion was that “misonidazole was not superior to hydroxyurea as an adjunct to radiation.” The failure of hydroxyurea to show a clear superiority over misonidazole calls into question the inherent benefit of hydroxyurea, although this arm became the control arm for other GOG studies.

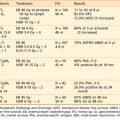

A series of landmark randomized trials were published in 1999. The RTOG protocol 90-01 randomized 403 patients with advanced cervical cancer stage to radiotherapy to pelvis and para-aortic lymph nodes or pelvis radiotherapy with two cycles of fluorouracil (FU) and cisplatin. Patients randomized included stages IIB-IVA, and stage IB-IA with tumor diameter at least 5 cm or involvement of pelvic lymph nodes. With a median follow-up of 43 months, there were statistically significant improvements in survival and disease-free survival at 5 years favoring the chemoradiotherapy group. The local-regional recurrences and distant metastases were significantly less in the chemoradiotherapy group.80 The GOG protocol randomized patients with locally advanced cervical cancer to radiotherapy and one of three chemotherapy regimens. Patients who received two of the three regimens that contained cisplatin had higher rates of overall survival and progression-free survival.81 Another GOG protocol evaluated the role of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with bulky stage IB cervical cancers (tumor diameter greater than or equal to 4 cm). All patients were treated with radiotherapy following adjuvant hysterectomy. Patients were randomized to weekly cisplatin versus radiotherapy alone. The 4-year overall survival and progression-free survival were significantly better in the group that received chemotherapy.82 Concurrent chemotherapy with extended-field radiation therapy has also been shown to be feasible for patients with metastatic disease to para-aortic lymph nodes. Results of these trials established the role of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced cervical cancer; the role of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy remains to be defined.

Bulky lesions, those exceeding 4 cm in maximum dimension, and endophytic lesions with significant extension into the lower uterine segment can be approached in a variety of ways. It is imperative, however, to first fully establish the shape and direction of growth of disease at the onset, especially in adenocarcinomas. External-beam therapy is necessary at the outset to allow tumor shrinkage for proper placement of tandem and colpostats. It is advisable to proceed with brachytherapy when the tumor has shrunk to less than 4 cm in diameter unless the tumor is eccentrically located to one side. A balance is necessary between tumor shrinkage and the inevitable restriction of the vaginal fornices that occurs with increasing external-beam dose. Doses as high as 45 Gy may be required to allow enough reduction in tumor size to proceed with an insertion, but doses in excess of 45 Gy before placement of a midline bar should be avoided because the risk of damage to bladder and rectum is directly related to the external dose to these organs.51,73 For larger lesions confined to the cervix, doses to the tumor or point A in the 85 Gy region are recommended if no adjuvant surgery is planned. In cases in which an extrafascial hysterectomy is deemed necessary, the total dose to point A should be confined to 70 to 75 Gy, and the pelvic nodal dose should be held at 45 Gy.

Adjuvant Hysterectomy

A routine adjuvant hysterectomy in all cases of bulky disease is not recommended. Citing an increased risk of central failure after radiation therapy alone, Rutledge and colleagues in 1976 published recommendations for adjuvant extrafascial hysterectomy after radiation therapy for patients with bulky cervical cancers measuring 6 cm or greater in diameter with lower uterine segment involvement, presenting the results of 212 patients so treated at M.D. Anderson Hospital from 1954 to 1967.83 A vesicovaginal fistula rate of 4.1% was reported after the combined procedures in a later report (four times the rate seen with radiation therapy alone). A prospective randomized trial, initiated by the GOG and RTOG in 1984 and closed in 1991, randomly assigned patients with lesions 4 cm or greater in maximum diameter to receive radiation alone (80 Gy to point A, 55 Gy to point B) or reduced radiation (75 Gy to point A), followed in 6 weeks by an extrafascial hysterectomy. There was no statistical differences in survival, between the two arms.84

Distant dissemination of disease remains a problem in larger tumors. Perez reported that IB/IIA patients with 3 to 5 cm lesions had pelvic failure rates of 15% to 28% and distant metastatic rates of 27% to 30%.85 These numbers rose to 20% to 30% and 37% to 57% for patients with tumors 5 cm or greater in size. Eifel found that disease-free survival dropped to 71% for patients with tumors 5 cm or greater in diameter, although pelvic tumor control rates remained at 85%.86

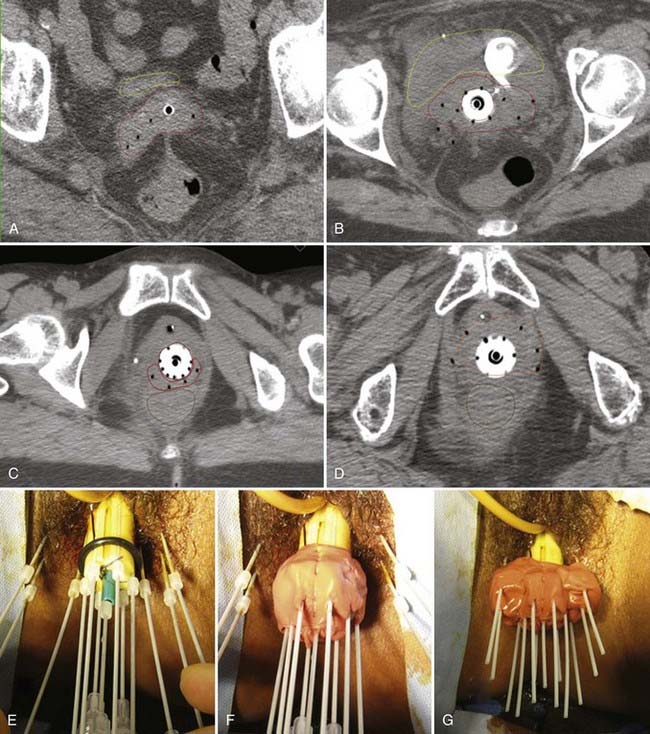

Stage IIB-IVA

Disease extension into the parametria is a contraindication to radical hysterectomy, because the chance of cutting through tumor is high. These patients are ideally managed by definitive chemoradiotherapy. As in cases of large IB tumors, external-beam therapy is first administered to allow tumor shrinkage. Generally, 45 Gy is administered via whole-pelvis fields, followed by two insertions to bring the paracervical dose to 85 Gy total, with parametrial boosts to the involved sides of 50 to 60 Gy. This final parametrial dose should take into account the dose administered externally as well as the dose from the brachytherapy. In patients whose disease is massive, treatment with an interstitial template may be more appropriate. Central control rates of 78% and pelvic control rates of 69% to 83% have been reported. Overall survival rates of radiation alone are 60% to 68%.37,74,87

Patients with stage III disease have a 17% to 67% chance of pelvic failure when treated with radiation alone.88,89 These results differ according to the bulk of disease, the presence of unilateral versus bilateral pelvic sidewall involvement, the presence or absence of lower vaginal involvement, and the type of brachytherapy used. Involvement of the lower portion of the vagina represents one of the most challenging situations encountered by the radiation oncologist; fortunately, it is a rare condition, composing only 1% to 3% of all cases of stage III disease.88,89 The approach depends on the extent and location of vaginal involvement, as well as the initial response to external-beam radiotherapy. Extension into the middle or lower third of the vagina is not adequately encompassed by tandem and colpostats. After initial external-beam therapy, response is assessed and the residual disease clearly defined in terms of its thickness and location. Brachytherapy plays an essential role in managing this portion of the disease, but care must be taken to respect the normal tissue tolerances of surrounding structures. Minimum tumor doses, in addition to the doses to the vaginal surface and normal tissues, must be followed closely. The goal is to deliver 85 Gy to the tumor volume while keeping the dose to the lower third of the vagina and vulva at 60 to 70 Gy. A tandem and cylinder with additional surface catheters and interstitial catheters is used to maximize the number of source positions in the region to optimize the dose distribution. Special attention should be given to dose at the skin-catheter interface. This is best achieved using 3-D planning technique and skin marker or molding. Pelvic control rates of 71% to 72% were reported for two small series of patients with IIIA disease from M.D. Anderson Hospital and Yale, in which most patients received a combination of external-beam and intracavitary or interstitial brachytherapy. Actuarial survival rates at 5 years range from 37% to 58%.88,90

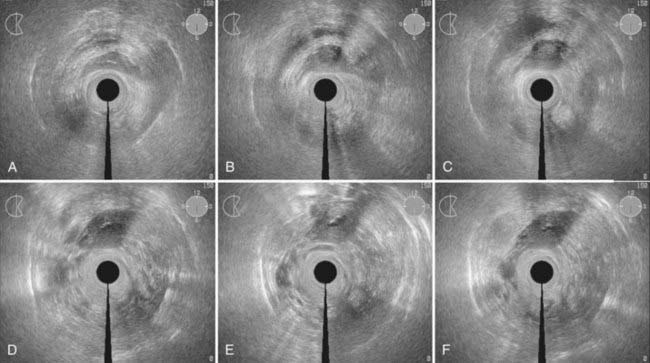

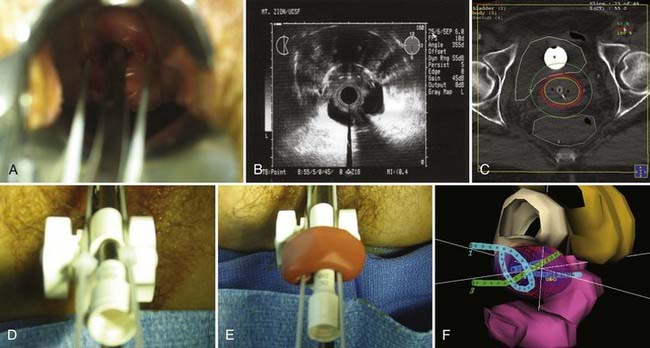

Disease with extension to the side walls (stage IIIB) has a 45% to 50% chance of locoregional failure when treated with standard tandem and colpostats in addition to external-beam therapy.36,89 An additional interstitial catheter can be added to complement the intracavitary system. To improve the placement accuracy of these interstitial catheters, a transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)–guided technique combined with a template has been described.91 At the University of California–San Francisco (UCSF) we have been using a TRUS-guided free-hand technique to combine our interstitial catheters with the existing intracavitary systems. A more detailed description is provided later in this chapter. In patients not amenable to implant or insertion, external-beam therapy to a dose of 65 Gy, coming off all small bowel after 50 Gy, may have to suffice. Pelvic control rates for all stage III disease presentations are in the range of 50% to 60%, with overall survival rates of 30% to 55%.36,37,74,87,89

For patients with bladder invasion but minimal or no parametrial invasion (stage IVA), an aggressive approach, including an anterior exenteration, is warranted. Likewise, those with extension into the rectum are candidates for posterior exenteration. Alternatively, definitive irradiation has been successful. Reports from Yale and M.D. Anderson Hospital revealed a low but significant cure rate of 18% to 46% depending on the aggressiveness of the treatment and the lateral extent of tumor.92,93 The dose to the bladder is higher than is acceptable in cases without bladder involvement, because the risk of fistula formation is weighed against the prospects of an anterior exenteration. If more extensive parametrial extension is noted, definitive irradiation is the preferred approach. The decision to proceed with palliative or curative radiation must be based on an awareness of the full extent of disease (nodal spread, distant metastases), local aggressiveness (existence of fistulae or ureteral obstruction), the patient’s overall medical status, and the patient’s desires.

Palliative radiotherapy in the setting of advanced carcinoma of the cervix should be tailored to the patient’s overall condition. The rapid fractionation approach tested by the RTOG in protocol 85-02 involved the delivery of 3.7 Gy twice daily for 2 days for a total dose of 14.8 Gy.94 This is repeated after a 2- to 4-week break. After a final 2- to 4-week break, the field is reduced to exclude all small bowel and a third session of four treatments is administered for a total dose of 44.4 Gy. A tumor response rate of 42% was seen after completion of all three courses with response rates (complete and partial) of 75% for pain, 98% for bleeding, and 83% for tenesmus. The treatment course was well tolerated with a severe complication rate of only 5 of 132 patients (4%).

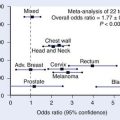

Hyperthermia

The role of combined hyperthermia with radiotherapy has not been clearly established. The earlier prospective trial did not show any benefit of adding hyperthermia with radiotherapy.95 Failure to demonstrate the benefit of hyperthermia was proposed to be the result of inadequate delivery of hyperthermia to deep-seated tumor. More recently using modern hyperthermia delivery system, the Dutch Deep Hyperthermia Group conducted a prospective randomized trial that reestablished the role of hyperthermia for cerrical cancer. One hundred and fourteen patients with stages IIB-IV locally advanced cervical cancer were randomized to radiotherapy alone or radiotherapy with hyperthermia. There was significant difference in 3-year overall survival and local control favoring the hyperthermia group.96–99 The study is of particular interest because the benefit was seen in locally advanced disease and the toxicity associated with hyperthermia was minimal. The result of this trial has revived interest in hyperthermia with radiotherapy for treatment of cervical cancer.

Adjuvant Radiation After Hysterectomy

Patients at low risk for pelvic recurrence after radical hysterectomy who would not be expected to show any benefit from postoperative radiotherapy are those whose pelvic lymph nodes are negative and those with tumors less than 4 cm in maximum dimension, no evidence of lymphatic vascular invasion, and less than one-third of the thickness of the surgical stroma involved. The risk of microscopically involved nodes in these patients is less than 15%.70,71,100,101 The group of patients who might be expected to have improved local control are those found to have involved pelvic lymph nodes or positive parametrial or vaginal margins. For these patients who were found to have high-risk features, postoperative chemoradiotherapy has been shown to improve survival. In the Southwest Oncology Group trial the high-risk features were defined as positive pelvic lymph nodes, positive margins, and microscopic involvement of the parametrium. A group of 268 patients were randomized to concurrent chemoradiotherapy with cisplatin and 5-FU or radiotherapy alone. The chemoradiotherapy arm had a significantly improved overall survival and progression-free survival.102

The intermediate risk group includes those who do not fall into either of the previous categories. This group may be more likely to show a benefit from adjuvant radiation because their disease is in an earlier stage than those with positive nodal spread.32 Patients in this group include those who have positive lymphatic vascular space involvement and at least one of the following characteristics: deep-third penetration of the cervix, middle-third penetration with a tumor 2 cm or greater in diameter, or superficial-third penetration with clinical tumor size 5 cm or greater. Alternatively, those with no LVSI with tumors 4 cm or greater in size with deep- or middle-third invasion of the cervix are considered intermediate risk. GOG performed a randomized study address the role of postoperative radiotherapy in cervical cancer. A group of 277 patients were randomized to postoperative radiotherapy or no further treatment; all patients had at least two of the following risk factors: greater than one-third stromal invasion, capillary lymphatic space involvement, and large clinical tumor diameter. Adjuvant pelvic radiotherapy significantly reduced the risk of recurrence in patients.103

Patients found to have positive para-aortic nodes at the time of sampling have a poor prognosis, with survival rates as low as 9% to 29% at 3 years.29,40 In a review of 98 patients in GOG surgical studies who were found to have clinically undetectable para-aortic node metastases, median survival was 15.2 months with a 3-year actuarial survival rate of only 25%.104 A majority of these patients were treated with postoperative para-aortic radiation to doses of 40 to 60 Gy.

Elective Radiation of Para-Aortic Lymph Nodes

Two major prospective randomized studies have been carried out to determine the efficacy of treating the para-aortic nodes prophylactically in patients with cervical cancer. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer randomly assigned 441 patients with stage IB through IVA disease, with no clinical or radiographic evidence of para-aortic spread, to receive pelvic radiation either alone or in conjunction with 45 Gy para-aortic radiation.107 No improvement was seen in local control or survival with the addition of para-aortic radiation, although there was a decrease in para-aortic and distant recurrence rates seen in the extended field group. Small bowel injury occurred in 0.9% of patients in the pelvic-only group versus 2.3% in the extended-field group. The severe complication rate in the para-aortic radiation arm was approximately twice that of the pelvis-only arm.

The RTOG study was limited to patients with bulky stage IB/IIA disease and those with any stage IIB disease, eliminating those patients with low-volume disease who might not be expected to show a benefit of the prophylactic extension of the field, as well as those with more advanced stage III disease in whom both local control and distant dissemination might mask any potential benefit of para-aortic radiation.108 The 5-year survival rate was significantly better in those patients who received prophylactic para-aortic radiation, 66% versus 55% (P = 0.043). The incidence of severe and life-threatening complications was similar for both groups. The extended-field arm became the control arm in the next RTOG trial (RTOG 9001) comparing extended-field radiation to pelvic radiation plus concomitant chemotherapy with 5-FU and cisplatin. The result of this trial showed the benefit of chemotherapy, and elective radiation of the para-aortic lymph node is now less commonly used.

In RTOG protocol 9210 patients with positive para-aortic lymph nodes were treated with concomitant 5-FU and cisplatin with twice-daily fractionation of 1.2 Gy delivered to the pelvis (60 Gy) and para-aortic (48 Gy) regions, followed by brachytherapy. Unfortunately, this combination resulted in an unacceptable high rate of grade 4 late toxicity, and did not an show improved results.105,106 However, there still may be a role for treatment of the para-aortic lymph node in combination with chemotherapy for patients with a known positive para-arotic node or high risk for involvement of the nodes.109,110 Multiple phase II studies have demonstrated the safety of this approach.110a,b A multivariate analysis suggests patients with a high squamous cell carcinoma antigen level, pelvic lymphadenopathy, or advanced parametrial involvement are predisposed to para-aortic node recurrence after definitive radiotherapy.110c At UCSF, patients with known pelvic nodal involvement and patient with pelvic side wall extension are recommend to have elective treatment of para-aortic nodal radiation because of high risk of recurrence.

Radiotherapy After Simple Hysterectomy

A simple hysterectomy is inadequate treatment for cervical cancer that invades deeper than 5 mm (stage IA2) or that invades deeper than 3 mm in the presence of LVSI. Unfortunately, some patients who undergo simple hysterectomies for benign conditions may be found to have invasive cancer at the time of pathologic examination.111 Two treatment options are available: immediate reoperation with radical parametrectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection or postoperative radiation.112 Surgery results in a 5-year disease-free survival rate of 82% to 96% in patients with no gross residual disease.111,113 The radiation approach depends on the volume and location of residual disease. Patients with no disease or microscopic disease only at the margins are approached with whole-pelvis radiation to a total dose of 45 to 50 Gy. An additional boost to the upper-third of the vaginal cuff to 60 Gy may be added using brachytherapy. Disease-free survival rates at 5 years of 71% to 90% are reported using this approach.113 For patients with gross residual disease, exenteration has produced approximately a 39% disease control,114 versus 23% to 43% for aggressive radiation intervention.113 Gross residual disease, which responds well to external-beam radiation therapy, may be treated with intracavitary brachytherapy, whereas greater residual volumes of disease should be considered for perineal interstitial templates to boost the residual disease sites to 65 to 70 Gy minimum tumor dose.

Cervical Stump

The performance of a supracervical hysterectomy is controversial in the management of benign diseases. Although it may be a less extensive surgery than a simple hysterectomy with less risk of urinary complications and fewer changes in the patient’s sexual activity, it is associated with the development of cervical malignancies.115–117 Although surgery may be feasible if the disease presents as stage I, the risk of metastatic disease remains. The ability to deliver curative radiation with brachytherapy is obviously hampered by the lack of a normal uterine canal for tandem placement. In a multi-institutional study of 213 cases of cancer of the cervical stump in France from 1970 to 1987, 50% were found to be CIS/stage I/stage IIA.115 The majority of patients were treated with external-beam radiation and brachytherapy consisting of a short tandem (when possible) with vaginal colpostats, or vaginal cylinders for more extensive disease in the vagina. Early stages (I-IIA) had an 80% local regional control rate at 5 years. Stages IIB-IIIA had 70% local regional control rate and stage IIIB only 55%. Overall, distant metastases developed in 19% of patients. Stage II patients who received external-beam radiation alone had only a 38.5% local-regional control as opposed to 81.5% for those that received external-beam radiation and brachytherapy. Grade 3 and 4 complications were seen in 13% to 23% of cases depending on the stage, with three fatal complications reported, indicating the increased risk associated with aggressive intervention when compared with similar treatment in patients with an intact uterine corpus. Kovalic et al. reported on 70 patients treated at Mallinkrodt from 1956 to 1986, of whom 67 received brachytherapy as part of their treatment and 16 also underwent surgery.117 The 10-year actuarial survival rate was lower in patients with stage IB disease of the stump compared with similar patients with stage IB disease of the intact uterus (50% versus 76%), but for all stages, the actuarial survival rates were comparable. Through the use of appropriate rectal and bladder shielding, the complication rate was lower in those patients treated only with radiation and no surgery, compared with other studies.

Cervical Cancer in the Setting of Human Immunodeficiency Virus

In the intermediate group, those with an immune status in decline, aggressive therapy is still warranted, but it must be tempered by an awareness of the risks of increased intolerance to radiation as well as the profound risk of development of concomitant opportunistic infections. Reports of intolerance (gastrointestinal [GI], skin, and hematologic) to aggressive treatment in HIV-positive patients with locally advanced cervical disease in developing nations bring up the difficult question of how best to manage such patients in settings where medical resources are limited or stretched.118–121 An attempt to answer this question of tolerance was mounted by the GOG, but a decline in the incidence of invasive cervical cancer among HIV-positive women in the United States because of intensive cervical screening in this population resulted in a failure to accrue adequate numbers.122 The maximal management of this cohort, therefore, varies tremendously worldwide, depending on available resources. HAART should be maintained, and radiation fields should be kept as tight as possible to reduce irritation to bowels that may already be plagued by offenders such as cryptosporidiosis, mycobacterium avium intracellulare, or cytomegalovirus. Brachytherapy alone might be preferred for patients with early stage I disease, balancing the need to control clinically uninvolved nodes that might be microscopically positive against the potential for increased marrow suppression. The use of chemotherapy concurrent with radiation should be used judiciously in patients with more advanced disease, with the use of colony-stimulating factors to reduce the degree of iatrogenic immunosuppression.

Cervical Cancer and Pregnancy

The incidence of cervical cancer during pregnancy varies from 1.6 to 10.6 cases per 10,000 pregnancies.123–126 The treatment approach differs depending on the gestational age of the fetus and the stage of disease at diagnosis as well as the informed consent of the patient. In the first two trimesters, the standard of recommendation is termination of the pregnancy and immediate hysterectomy or radiation for all but the most limited cases of invasive disease (microinvasive), which has been approached with cautious conization, rigorous follow-up, and hysterectomy after a full-course delivery in isolated cases. There is a case report of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by elective cesarean delivery and radical hysterectomy performed at 32 weeks gestation.127 For patients in the late third trimester, early delivery via cesarean section at the time of fetal maturity may cause only minimal delay in dealing with the cancer. The difficulty arises in patients in the early part of the third trimester who are desirous of maintaining the fetus, but in whom a delay in intervention may decrease the expected survival rate. The survival for stage I patients using immediate intervention is excellent.126 In a small series of patients with early stage disease who elected to continue their pregnancies, delaying their therapeutic intervention, delay did not have a negative affect. In a series of eight patients with stage IA/B disease who had delays from 53 to 212 days, no progression of disease was documented. In a historical review of 51 patients in the literature who delayed therapy, 77% of stage IA cases had attained no-evidence-of-disease (NED) status and 80% of stage IB cases were NED, although the follow-up was short in some cases.126 In patients whose pregnancies are in early stages and who desire intervention to terminate the pregnancy, surgery or radiation may be selected based on the stage of disease, with cure rates similar to those expected in the non-pregnant patient.

Management of Treatment-Related Side Effects

Patient Follow-Up and Management of Complications

Reports of incidence of severe complications requiring medical intervention, hospitalization, or surgical intervention or resulting in death provide conflicting evidence as to what factors are the most important in predicting adverse sequelae.128–130 Most commonly discussed are brachytherapy doses; doses to various rectal, bladder, and paracervical points; and history of prior procedures or illness. The comparison of brachytherapy doses between separate institutions is made difficult by the various manners in which the normal tissue dose points are defined. Using the reference points defined in the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements (ICRU) 38 report, Perez et al. described the incidence of major sequelae in 1211 patients treated at Mallinkrodt between 1959 and 1986.131 Those patients who received a dose of less than or equal to 80 Gy to the rectal point had a 2% to 3% incidence of major rectal complications, compared with a rate of 6% to 13% at doses greater than 80 Gy. Urinary sequelae did not correlate well with dose to the bladder point, with a range of 2% to 6% at all doses analyzed. Small bowel injury increased as total dose to the lateral pelvic wall rose above 60 Gy (3.6%). In an earlier report, Perez had pointed out that age, prior surgery, history of pelvic inflammatory disease, external-beam dose, and type of midline block used all failed to correlate with major sequelae rate.129

Lanciano and colleagues in the Patterns of Care Study reported a crude complication rate of 9.8% with 3- and 5-year actuarial rates of 10% and 14%, respectively, in 1558 patients treated only with radiation for all stages of disease at a large number of institutions in the United States.51 Of all complications, 61% occurred in the large and small bowel, 21% in the bladder, and 10% in the vagina. Of these complications, 64% required surgical correction, and 9% were fatal (total of 0.8% fatal complication rate). The median time to development of complications in the bowel was 13.5 months, bladder 23.2 months, and vagina 17.4 months. In this multivariate analysis, five factors were associated with an increased risk of major complications: the use of external-beam therapy, dose per fraction in excess of 2 Gy, the use of radium rather than cesium, paracentral dose, and dose to the lateral parametrium.

Target organ threshold doses are not by themselves reliable predictors of the risk of serious radiation sequelae, because they fail to take into account the volume of the organ incorporated in the high-dose region. This volume will vary significantly based on the total external-beam contribution to the organ and on the manipulation of source locations and dwell times possible with currently remote afterloading optimization systems. Crook and colleagues have recommended the use of a mean rectal dose (the average of the doses received at four different rectal points along the axis of the anterior rectal wall, in addition to the maximum rectal dose) to identify groups at low, intermediate, and high risk for major rectal sequelae.132 The critical dose is not a simple value at a point; rather, it is an estimate of the volume of tissue exposed to a high radiation dose from both the external and intracavitary components of treatment. Ideally, CT-based 3-D dosimetry with dose-volume histograms for tumor and normal tissues will allow more accurate prediction of and avoidance of major complications.

The risk of damage to the small bowel is related to the total dose delivered to the pelvis, the fraction size per dose, and the presence of physical factors such as multiple abdominal surgical procedures or pelvic inflammatory disease.51,129,130,133,134 Technical factors such as the treatment of one field per day, lower energy machines, or extended field coverage of the para-aortic nodes have also been implicated.130,135 Doses of more than 45 Gy to the entire pelvis are associated with a rising incidence of the development of intermittent or surgical small bowel obstruction.130 Methods proposed for the reduction in risk of small bowel morbidity include the treatment of all fields each day, the use of megavoltage equipment, treatment with the bladder full, and the placement of an omental or mesh sling to remove bowel from the field of radiation at the time of preradiation surgical exploration or lymphadenectomy.130,136 The use of an extraperitoneal, rather than a transperitoneal approach for para-aortic lymph node sampling is associated with a reduction in radiation risk to small bowel and is the recommended approach in patients entered into GOG studies requiring para-aortic lymph node sampling.108,137 Overall, for patients treated with radiation for carcinoma of the uterine cervix, the crude incidence of small bowel obstruction was 2% to 3% in the Perez report,131 4% in the Patterns of Care Study,51 and 4% in the pelvic radiation therapy–alone arm of the RTOG para-aortic study.135 This incidence increases to 9%, however, with extended-field radiation to cover the para-aortics, and to 17% in patients so treated who had a prior history of abdominal surgery.135 Studies that have pushed the dose to 60 Gy have resulted in severe GI complication rates of as high as 57%.104

Other risks associated with the treatment of cervical cancer include the development of thromboembolic phenomena or major cardiac complications during or immediately after brachytherapy procedures for surgical carcinoma, although the reported incidence is quite low at 0% to 4%.138,139 One particularly bothersome side effect of radiation for cervical cancer is the development of vaginal adhesions, vaginal shortening, and, potentially, total agglutination of the vagina. Small adhesions form quickly in the irradiated patient, which can make sexual intercourse and future pelvic examinations quite painful. Therefore, at the completion of therapy, the patient is instructed in the use of a vaginal dilator, to be used on a daily or every-other-day basis for 5 to 10 minutes. The patient is started with a small dilator, instructed in its use with lubricating jelly, and encouraged to begin using it on a very regular basis. Dryness of the irradiated vagina is a common side effect, because of a combination of direct radiation effect and the onset of menopause. Vaginal lubricants and topical estrogen creams are beneficial in partially relieving these symptoms.

The risk of second malignancies rises over time after radiation for carcinoma of the cervix, although the exact increase over the rate expected in the general population is difficult to assess. Several reports suggest that the increase is not significant overall,140 although some specific subtypes of cancer are seen with an increased rate over expected incidence rates.141 Analyzing data from a combination of the Connecticut Tumor Registry and SEER databases, Rabkin and colleagues reported on close to 25,000 women treated for cervical carcinoma with either surgery or radiation who were long-term survivors.141 The RR of developing a second tumor after radiation was greater than 2.5 for the development of anal carcinoma (4.6), larynx (3.3), lung (3.0), vulva or vagina carcinoma (5.6), bladder (2.7), and bone (2.7). However, the presence of shared causal factors, such as HPV in anal, vulvar, and cervical malignancies, or excess smoking in the population of cervix and lung cancer patients, makes it unclear that the treatment contributed to this excess risk.140 Information from the Danish Cancer Registry in approximately 45,000 patients treated between 1943 and 1982 revealed an excess of only 64 cases per 10,000 women per year of tumors in the pelvises of irradiated patients, reaching a maximum at 30 years, indicating the need for prolonged follow-up in assessing the true increased incidence of second malignancies.142

Surgical Technique

An excellent review of the classes of hysterectomy was published by Piver and colleagues in 1974.143 These procedures differ in the handling of the uterine arteries, the ureters, the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, and the vaginal cuff, as well as adjacent organs. The morbidity and mortality rates increase gradually as progress is made toward the more extensive resections. The gynecologic oncologist adopts the procedure that is appropriate for the size and extent of the cervical neoplasm.

Radiation Technique

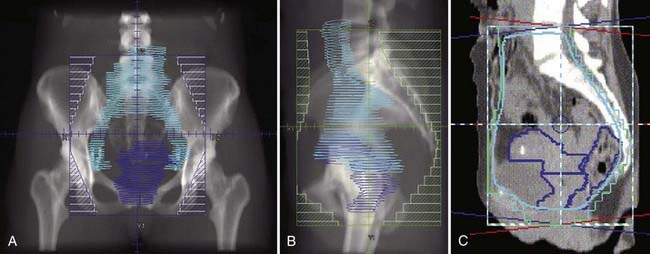

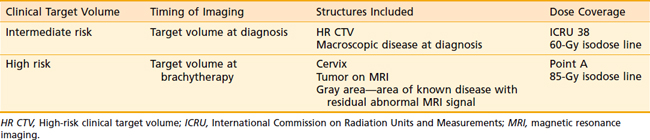

The goal of radiotherapy is to deliver the appropriate dose to the anatomic structure based on the risk of tumor burden. To achieve this goal it is important to first determine the planned dose for each target volume. For the lymph node region with a lower risk of harboring microscopic disease, the goal is to deliver 45 to 50 Gy while minimizing the dose to organs at risk. An enlarged lymph node should be boosted to a dose of 54 to 60 Gy depending on the size of the lymph node and the tolerance of organs at risk near the lymph node. If the dose required to sterilize the tumor is greater than can be delivered safely using available radiotherapy techniques, then the lymph node should be resected prior to the beginning of radiotherapy. In patients with an intact uterus, the size of the primary cervical tumor is often greater than can be controlled based on maximum dose that can be delivered with external-beam radiotherapy alone. Fortunately, it is usually possible to deliver the necessary therapeutic dose of 85 Gy safely using brachytherapy (Table 48-5).

Table 48-5 Tumor Burden and Radiation Doses Needed for Control

| Microscopic disease | 45-50 Gy |

| 1-2 cm | 60-70 Gy |

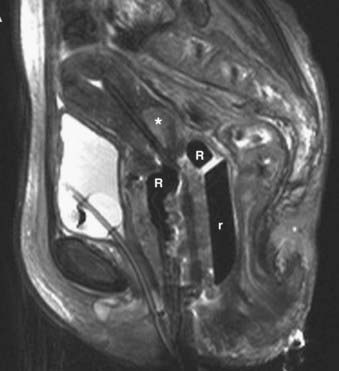

| 2-3+ cm | 70-90 Gy |