66 Cancer of the Skin

Epidemiology, Etiology, and Pathogenesis of Basal and Squamous Cell Carcinomas

Nonmelanoma skin cancer represents the most common malignancy in humans. In the United States, the incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer approaches that of all noncutaneous cancers combined. According to the American Cancer Society, more than 1 million new basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin occurred in the United States in 2008,1 with one in five Americans developing skin cancer during their lifetime.2 As cases are often not reported to cancer registries, the actual incidence of these cancers likely far exceeds these estimates. Despite increased knowledge and public education regarding the causes of skin cancer and modes of prevention, the incidence of nonmelanoma cutaneous cancer continues to rise. The cause of this phenomenon is largely speculative but is believed to be due to changes in both sun exposure habits among patients and improved detection. Some researchers have also hypothesized that stratospheric ozone depletion may be a contributing factor.3

Basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas account for approximately 80% and 20% of nonmelanoma skin cancer, respectively.4 The term nonmelanoma skin cancer is often used to refer to these two histologies; however, other types of nonmelanoma skin cancer, such as adnexal carcinomas (involving the sweat and sebaceous glands) and sarcomas, are less common and differ considerably in their cell type, behavior, and epidemiologic features. Although basal cell carcinoma rarely metastasizes, the morbidity associated with this type of skin cancer can be significant. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma carries an increased risk of metastasis and an overall worse prognosis. An estimated 1000 to 2000 deaths result each year from nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, with population-based mortality rates of approximately 0.05% and 0.7% for basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, respectively.5

Because damage from ultraviolet (UV) light is the most common (and preventable) predisposing factor, there is a relatively low incidence of skin cancer in dark-skinned people, who are protected by the large amount of melanin in their skin. On the other hand, there is a relatively high incidence in whites of Irish, Scottish, or English descent who have red or blond hair and blue or green eyes and who burn rather than tan when in the sun. Damage to the skin from UV light appears to be cumulative with time. Consequently, skin cancer usually develops after the age of 40 years.6–10 The incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer correlates with skin phenotype, the amount of average annual UV radiation, and geographic latitude, with the highest incidences reported in countries such as Australia and South Africa.8,11–19 Trauma and chronic irritation are additional risk factors. Skin cancers have been reported in scars resulting from vaccinations,20 tattoos,21 burns (Marjolin ulcer),22–24 and chickenpox25; in chronic nonhealing ulcers26; and at sites of prior ionizing radiation therapy and chronic radiation dermatitis.27 Other predisposing clinical settings include longstanding lesions of discoid lupus erythematosus,28–30 erosive or hypertrophic lichen planus,31 lichen sclerosus32; porokeratosis33,34; and nevus sebaceous.35 Occupational exposures to arsenic-containing pesticides, mineral oil, coal tar, soot, and polychlorinated biphenyls are associated with an increased risk for the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer.36 Another recent study suggested that the use of tanning beds significantly contributes to the incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer.37

Oncoviruses have also been implicated.38 Genetic disorders such as xeroderma pigmentosum,39 oculocutaneous albinism,40 epidermodysplasia verruciformis,41 dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa,34 nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS; Gorlin syndrome),42 Bazex syndrome,43 and Rombo syndrome44 are associated with an increased incidence of skin cancer.

Iatrogenic immunosuppressive therapy,45 especially in the organ transplant population,46,47 is an increasingly prevalent risk factor for developing skin cancer, and in particular squamous cell carcinoma. Organ transplant patients appear to have a 65-fold increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma and a 10-fold increased risk of basal cell carcinoma.48,49 Similarly, patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS),50 leukemia, lymphoma, or multiple myeloma have an increased risk of developing skin cancer.51 Persons with AIDS have a three- to fivefold increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer; in contrast to organ transplant recipients, the ratio of squamous cell carcinoma to basal cell carcinoma is approximately 1 : 7.52 Although basal cell carcinomas can be multiple in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) population, they are most often of the superficial subtype. Squamous cell carcinoma in HIV may be associated with younger age and in certain clinical circumstances, unusual human papillomavirus subtypes (anogenital, cervical, oral, and nail unit squamous cell carcinomas, and HIV-associated epidermodysplasia verruciformis). There is also a higher risk for aggressive behavior, seemingly unrelated to CD4 count. In general, skin cancers in immunosuppressed populations are more likely to be advanced; this subset of patients deserves close clinical monitoring.

Germline mutations in the human homolog of the Drosophila patched gene (PTCH) were first implicated in the pathogenesis of NBCCS (Gorlin syndrome) in 1996; in NBCCS, patients develop multiple and recurrent basal cell carcinomas beginning at a young age.53,54 Disruptions in the Hedgehog signaling pathway, which under basal conditions appears to be essential for normal embryonic development and tumor suppression, have since been found in sporadic basal cell carcinomas as well.55–57 Hedgehog pathway mutations are the most frequent genetic alterations in basal cell carcinomas and are likely sufficient for tumorigenesis. Mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene are commonly found in both basal and squamous cell carcinomas.58

Anatomy of the Skin

The three layers that make up the skin are the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue.36 The epidermis is a stratified squamous epithelium that is approximately 0.05 mm thick,59 and composed of the stratum basale, stratum spinulosum, stratum granulosum, and stratum corneum. In normal skin, transit time of a basal keratinocyte through the stratum corneum is approximately 4 weeks.60 The basement membrane zone separates the epidermis from the underlying dermis. The dermis, which is 1 to 2 mm thick, contains lymphatics, nerves, blood vessels, sweat, and sebaceous glands in a connective tissue stroma, and serves to provide both structural and nutritional support for the epidermis. The superficial portion of the dermis in continuity with the epidermis is called the papillary layer because of its projecting dermal papillae. The deeper portion of the dermis, which contains bundles of collagenous and elastic fibers, is called the reticular layer. Subcutaneous tissue lies deep to the dermis and supports the lymphatics, blood vessels, and nerves in loose connective tissue containing variable amounts of fat.

Pathologic Conditions and Clinical Presentation

Basal Cell Carcinoma Subtypes

There are several subtypes of basal cell carcinoma that differ in clinical presentation, histologic appearance, and behavior.37,61 Of the most common subtypes, nodular and superficial basal cell carcinomas typically demonstrate low-risk clinical behavior, whereas infiltrative, morpheaform, and micronodular basal cell carcinomas are more likely to recur, and be locally aggressive and destructive.

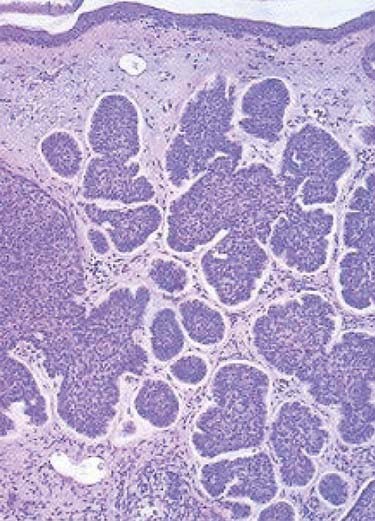

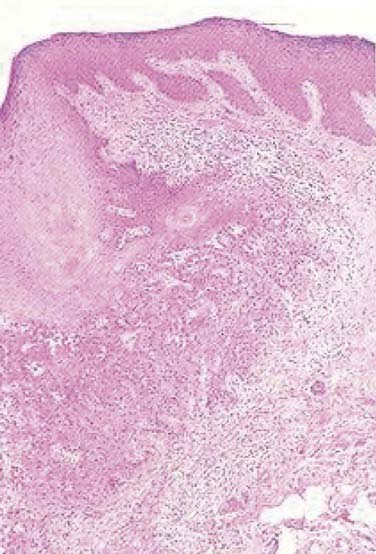

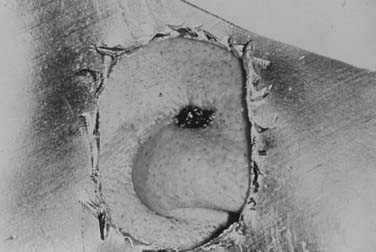

The nodular subtype, which accounts for approximately one half of all basal cell carcinomas, initially appears as a pink, translucent papule with prominent telangiectasias. As the carcinoma grows, it may develop central ulceration and crusting (“rodent ulcer”). Histologically, all basal cell carcinomas share common features including proliferations of basaloid keratinocytes in various configurations, often with apparent epidermal attachment, an associated fibromyxoid stroma, and tumoral-stromal clefting. The malignant cells in nodular basal cell carcinoma form dermal nests.62 At the periphery of the nests, the basaloid cells elongate in a parallel array, forming a palisading pattern. The malignant cells exhibit little pleomorphism, and mitoses are infrequent (Fig. 66-1). The clinical differential diagnosis of nodular basal cell carcinoma includes rosacea, acne, folliculitis, angiofibroma, benign adnexal tumors, and granulomatous disorders such as sarcoidosis and granuloma annulare. The superficial subtype, which accounts for one third of basal cell carcinomas, typically appears as a red, scaly macule or thin plaque located on the trunk or extremities. Histologically, the basaloid proliferations are smaller and more superficially located. The differential diagnosis includes actinic keratosis, squamous cell carcinoma in situ (Bowen disease), extramammary Paget disease, or a benign inflammatory lesion of psoriasis, tinea corporis, or nummular eczema. Infiltrative and morpheaform basal cell carcinomas present as light-colored atrophic macules that later become smooth, shiny, red to white, indurated plaques resembling scars, often with overlying telangiectasia. The margins of infiltrative and morpheaform basal cell carcinomas are difficult to assess clinically. Although the terms infiltrative and morpheaform are often used as synonyms, some authors prefer the use of infiltrative to describe tumors with jagged nests, and morpheaform for tumors in which thin strands of basaloid cells predominant within a fibromyxoid stroma. The differential diagnosis includes scleroderma, metastatic carcinoma, scar, and granulomatous disorders. Infiltrative and morpheaform subtypes account for 10% of basal cell carcinomas. Micronodular basal cell carcinomas may present nonspecifically as macules, papules, or thin plaques. On histopathologic examination, basaloid tumor nests are smaller than those of nodular basal cell carcinoma, but as compared with superficial basal cell carcinoma, may invade deeply. The pigmented subtype, which accounts for 1% of basal cell carcinomas and is considered by some authors a variant of nodular basal cell carcinoma, ranges in color from blue to black and can be difficult to distinguish from melanoma. This subtype occurs more often in darkly-pigmented individuals. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus, which accounts for less than 1% of basal cell carcinomas, presents as a flesh-colored, often pedunculated papule or plaque on the trunk or thighs. Histopathologic examination reveals thin anastomosing strands of tumor cells that extend from the epidermis, and are enmeshed in a fibrous stroma. Basosquamous carcinomas (metatypical carcinomas or keratotic basal cell carcinomas) occur almost exclusively on the face. These are uncommon neoplasms that demonstrate areas of squamous differentiation and whose clinical behavior sometimes resembles that of squamous cell carcinomas.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma Subtypes

On histopathologic evaluation, Bowen disease demonstrates full-thickness epidermal atypia, with more pronounced nuclear polymorphism and apoptosis than is seen in actinic keratosis. Other features include confluent parakeratosis, and, not infrequently, the adnexal extension of neoplastic cells. Invasive squamous cell carcinoma typically arises on a background of epidermal change consistent with actinic keratosis, and, less often, squamous cell carcinoma in situ. Invasive tumor lobules push downward from the overlying epidermis and detached tumor islands are noted within the dermis (Fig. 66-2). Both cytoplasmic and cystic keratinization may be observed. The degree of keratinocyte differentiation within these tumors is variable and an important prognostic factor. Other histopathologic risk factors include tumor thickness and depth of invasion, perineural involvement, lymphovascular invasion, and subtype. Pathologic subtypes associated with clinically aggressive behavior include adenoid (pseudoglandular), acantholytic, adenosquamous, and desmoplastic squamous cell carcinoma.

A few additional subtypes are clinically distinctive and noteworthy. Verrucous carcinoma is an indolent, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma that grows slowly as an exophytic, cauliflower-like lesion and may be associated with human papilloma virus infection. This variant of squamous cell carcinoma may arise in the anogenital region (Buschke-Lowenstein tumor), oral cavity (oral florid papillomatosis), or on the plantar surface of the foot (epithelioma cuniculatum). Spindle cell carcinoma, a rare subtype of squamous cell carcinoma, usually develops in sun-exposed areas in lightly-pigmented individuals older than 40 years of age.63 The prognosis primarily depends on the depth of invasion. Verrucous and spindle cell carcinomas are managed similar to more conventional squamous cell carcinomas.

Although keratoacanthomas were historically considered benign secondary to a natural history of spontaneous regression in some cases, they are currently viewed by most authors as a variant of squamous cell carcinoma. A keratoacanthoma presents as a rapidly enlarging papule that becomes a crateriform nodule with a central keratinous plug over a period of weeks to months. Some lesions may regress slowly over months to form an atrophic scar. Although keratoacanthomas are most often solitary, numerous clinical variants have been described, including multiple, grouped, giant, subungual, or intraoral lesions. Unusual presentations include keratoacanthoma centrifugum marginatum (a lesion that expands extensively to the periphery with central involution and atrophy), multiple spontaneously regressing (Ferguson-Smith), multiple nonregressing, and generalized eruptive (Grzybowski) keratoacanthomas. Multiple keratoacanthomas in association with sebaceous neoplasms, colon carcinoma, and other visceral malignancies characterize Muir-Torre syndrome. In most clinical situations, keratoacanthomas are best treated similar to conventional squamous cell carcinoma. Although intralesional FU or intralesional methotrexate may be used for multiple lesions, surgical excision is the most commonly performed procedure for a solitary keratoacanthoma. However, at sites such as the pinna of the ear, eyelid, nasal tip, nasal ala, or commissure of the lips, radiation therapy may provide better cosmetic and functional results. Shimm and colleagues described the treatment of 13 keratoacanthoma patients with radiation therapy.64 With a median follow-up of 41 months, the local control rate was 100% and the cosmetic results were excellent. For keratoacanthomas of 2 cm or less, Shimm and colleagues recommend a total dose of 25 Gy in five fractions on consecutive days, using superficial or orthovoltage x-rays. “Giant” (>2 cm) keratoacanthomas can be successfully managed with a total dose of 50 Gy in 15 fractions over 3 weeks using electrons.65,66

Routes of Spread

During weeks 4 to 8 of embryologic development, embryologic fusion planes are postulated to form at the junctions of various anatomic regions. Although embryologic fusion planes were traditionally thought to dictate the depth of invasion, horizontal growth, and area of recurrence of epithelial carcinomas,67–69 controversy has arisen as to whether these planes persist in adults and influence the spread of skin cancers.70,71

The perineural space represents a cleavage plane between a nerve and its surrounding sheath, and a pathway of apparently decreased resistance for the spread of skin cancer.72 Although small superficial cutaneous nerves are not uncommonly involved on histopathology in both squamous cell and basal cell carcinoma, large named nerve trunks are much less frequently affected.73 As the literature has often failed to differentiate between small and large nerve, microscopic and macroscopic (or clinical) perineural invasion, accurate estimates of incidence in each case are difficult to ascertain. Perineural inflammation in association with so-called skip areas, where no cancer cells are identified on the pathologic specimen,74 may be a clue to the presence of perineural tumoral invasion on more proximal sections of nerve.74,75 Notably, 60% to 70% of patients with pathologic evidence of perineural invasion by a basal or squamous cell carcinoma are asymptomatic.76–79 Once compression of a nerve or, less commonly, intraneural invasion72,77,80 develops, a patient is more likely to become symptomatic with anesthesia, paresthesia (formication, burning, stinging or shooting pain), facial muscle weakness, ptosis, diplopia, blindness, or stroke.76,77,81,82

Mohs noted perineural invasion in 0.9% of 2488 basal cell carcinomas in 1978.83 Basal cell carcinomas with evidence of perineural involvement are most often located in areas innervated by peripheral branches of the trigeminal and facial nerves.75 Basal cell carcinomas with perineural invasion are less common than their squamous cell carcinoma counterparts and are typically advanced, recurrent, or rarely metastatic when perineural invasion is present.84,85 Estimates of the incidence of perineural invasion in squamous cell carcinoma have ranged from 2.4% to 14%.74,78,83 Although microscopic perineural invasion can be an incidental finding in squamous cell carcinoma, it may also indicate a higher risk of local recurrence and even regional metastasis.86,87 It is clear that squamous cell carcinomas with macroscopic or clinical perineural involvement are associated with a higher incidence of regional and distant metastases.86–89 When squamous cell carcinomas involve the cranial nerves (most often the trigeminal and facial nerves), there may be significant morbidity and mortality, especially in cases with extension to the skull base and subsequent intracranial spread.

Other potential routes of spread for cutaneous carcinomas include perichondrial, periosteal, tarsal, and fascial planes, as well as along blood vessels and lymphatics.67

Staging

Some authors have postulated that basal cell carcinoma rarely metastasizes because it uniquely depends on stroma produced by dermal fibroblasts.90 Accordingly, the incidence of metastatic basal cell carcinoma is thought to be quite low, between 1 : 1000 to 1 : 35,000, and staging is infrequently required.85 The rare basal cell carcinoma that does metastasize is typically a large, ulcerative tumor for which repeated treatments over the years have failed. The most common metastatic site for basal cell carcinoma is the regional lymph nodes, although the lungs, liver, or bones may also be involved.91

The incidence of regional lymph node metastasis in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the skin varies widely in the literature. In general, small (<2 cm), thin (<4 mm), and primary squamous cell carcinomas are felt to be low-risk (<5%) for the development of nodal metastasis.92–94 Although high-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas can be associated with significant morbidity and mortality and must be identified early so that appropriate management can be recommended, universal and validated staging criteria are lacking. The current American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system (Table 66-1) groups all nonmelanoma skin cancers together (excluding carcinomas of the eyelid, vulva, and penis), and does not incorporate many important prognostic factors for squamous cell carcinoma.95,96 High-risk features that do appear to be predictive of metastatic disease include size larger than 2 cm, site (lip, areas with parotid drainage, scalp), incomplete excision and recurrence, thickness and depth of invasion (>4-5 mm depth, Clark level >III), histologic grade, histologic variant, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, and immunosuppression.78,89,92,96–110 Squamous cell carcinomas that arise in burn scars or osteomyelitic foci have also been shown to metastasize to lymph nodes at an increased rate, in 10% to 30% of cases.94 In light of the growing literature on high-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, revision of the AJCC staging system is underway. When a squamous cell carcinoma metastasizes to regional lymph nodes (usually parotid and cervical), surgery and postoperative radiation therapy provide better locoregional control than radiation therapy alone.111,112 The 5-year survival rate for patients with lymph node metastases is 25%.113 Like basal cell carcinomas, typical distant metastatic sites for squamous cell carcinomas are the lungs, liver, and bones.

Table 66-1 Classification of Carcinoma of the Skin (Excluding Eyelid, Vulva, and Penis) Rights were not granted to include this table in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book.

Diagnostic Studies

In the case of carcinomas involving the medial or lateral canthi of the eyes, one should consider obtaining either a computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, to assess the depth of invasion, because apparently superficial cancers sometimes extend along the wall of the orbit (Fig. 66-3). If perineural invasion is present or suspected, MRI is the imaging study of choice to determine if retrograde spread of the carcinoma has occurred.114 However, in some cases, abnormal radiographic findings, for example, nerve or foramen enlargement, may not develop until late in the course of the disease.72,74,75 If there is suspicion that a locally advanced carcinoma has invaded underlying bone or metastasized to the regional lymph nodes, or distant sites, a CT, MRI, or positron emission tomography (PET) scan should be obtained. Notably, PET scans may offer superior sensitivity and specificity for the detection of metastases, when compared with more conventional imaging modalities such as CT or MRI. Adams and colleagues reviewed the detection of cervical lymph node metastases (117 metastases confirmed by histopathologic examination in 1284 lymph nodes) from head and neck carcinoma, and found that fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET correctly identified nodal metastases with a greater sensitivity (90%) and specificity (94%), than either CT (sensitivity 82%, specificity 85%) or MRI (sensitivity 80%, specificity 79%).115

Treatment Options

Because most skin cancers can be treated with several different therapeutic approaches, it is important to select the most appropriate treatment. A number of criteria are useful in making this decision. Stratification of tumors into low-risk or high-risk categories should be performed. Consideration should be given as to whether single or multiple cancers are present. The age and general health of the patient, cure and complication rates, cosmetic and functional results, convenience, and cost of the different therapeutic approaches should also be discussed. For high-risk tumors, multispecialty consultation as well as preoperative imaging studies should be considered to facilitate the development of a rational therapeutic plan. The role of sentinel lymph node biopsy remains poorly defined.92 Metastatic carcinomas may need a combination of treatment modalities for local control and therapy of regional and distant metastases.

There are several forms of treatment for basal and squamous cell carcinomas, including cryosurgery, curettage and electrodesiccation, chemotherapy, surgical excision, Mohs micrographic surgery, and radiation therapy. Cryosurgery or cryotherapy involves fast freezing and slow thawing via the application of liquid nitrogen to the skin.116 Although cryosurgery is convenient and relatively inexpensive, it provides no therapeutic or cosmetic advantage over other more commonly used treatment modalities and thus its use for skin cancers should be considered largely historical. The technique involves freezing of the carcinoma to a goal tissue temperature of −70° C along with a 3- to 5-mm margin of normal tissue; the ice block is allowed to thaw, and the process is repeated one or two times to cause selective tumor necrosis. Adverse reactions include significant pain, crusting, edema, bulla formation, and skin sloughing. As melanocytes are particularly sensitive to cryosurgery, hypopigmentation is an expected complication. Contraindications include high-risk or recurrent tumors and patients with known cold urticaria, cryofibrinogenemia, cryoglobulinemia, or Raynaud disease. Relative contraindications include patients with darkly pigmented skin, tumors overlying superficial nerves or in anatomic regions subject to scar and retraction.

Curettage and electrodesiccation is commonly used for previously untreated superficial skin cancers. With a curette, the comparatively soft and friable cancer-containing tissues are scraped away, leaving behind firmer uninvolved tissue. After each curettage, the wound is electrodesiccated to encompass a 1-mm margin beyond the curetted tissue. This process is typically repeated for a total of three cycles. Patients must be cautioned that prolonged postoperative wound care will be required as the wound granulates and reepithelializes. Scarring is generally cosmetically acceptable, but may lead to a hypertrophic or hypopigmented scar at the site of treatment. Like cryosurgery, curettage and electrodesiccation is an effective method of managing primary superficial or nodular basal cell carcinomas; squamous cell carcinomas in situ; and small, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas with clinically distinct margins. As no pathologic specimen is generated to indicate complete treatment, this approach is not recommended for high-risk or recurrent tumors, carcinomas involving regions prone to scar with retraction, or carcinomas involving scar tissue, cartilage, or bone.117,118

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) involves the use of topical, intralesional, or systemic photosensitizers in combination with a photoactivating light source to create cytotoxic oxygen radicals and achieve tumoral tissue destruction. Topical PDT is typically limited to the treatment of multiple actinic keratoses or small superficial skin cancers.119–121 Curettage is often performed to debulk the tumor; this is followed by application of either 5(δ)-aminolevulinic acid HCl (ALA) and methyl-esterified ALA, and exposure to a variety of light sources. Side effects from topical PDT include mild pain, local site reactions, and sensitivity to ambient light for 2 to 7 days. Caution should be employed in patients with a history of porphyria or other photosensitivity disorders, and with prior or current herpes simplex virus infection.

Topical 5-FU chemotherapy is most often used to treat multiple actinic keratoses, superficial basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma in situ.119,122,123 Imiquimod cream, a Toll-like receptor 7 agonist, induces interferon-alpha and other T helper-1 cytokines, and may be used for similar indications.124–127 Although some authors have used topical imiquimod for the treatment of nodular basal cell carcinoma, cure rates are inferior when compared with superficial basal cell carcinoma.124,125 Both topical 5-FU and imiquimod are generally well-tolerated, with side effects limited to local skin reactions. Intralesional FU or methotrexate have been used for the treatment of keratoacanthomas.

Thus far there have been few reports regarding the use of systemic chemotherapy for basal and squamous cell carcinomas. Overall, the results achieved with other therapeutic approaches have been excellent, so systemic chemotherapy has been unnecessary in most patients. However, advanced skin cancers do respond to 5-FU, cisplatin, bleomycin, doxorubicin, isotretinoin, interferon-alpha, or a combination of agents. For patients treated with chemotherapy alone, response rates have characteristically ranged from 70% to 80%, with a complete response rate of 30%.128–130 These results are not surprising considering the high response rates that have been achieved when squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck have been treated with two to three cycles of chemotherapy before radiation therapy.131 Approximately half the responses have lasted longer than 1 year.128 In the case of locally advanced or metastatic carcinoma of the skin, chemotherapy concurrent with radiation therapy may be considered.132 Further investigations are needed to evaluate the potential of capecitabine, an oral pro-drug of 5-FU with a more favorable safety profile than its parent drug,133 and the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors,134 which have recently emerged as novel treatment strategies for aggressive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin.

Advances in reconstructive techniques have helped make surgical excision a commonly used therapeutic approach. Standard surgical excision with predetermined margins allows pathologic assessment of the extent of a carcinoma via the bread-loaf technique of tissue sectioning, but assesses only 0.01% of the total margin and may be difficult in older patients with either a large solitary carcinoma or multiple small carcinomas in the same region.135 With Mohs micrographic surgery, horizontal layers of tissue are serially excised with a beveled edge, and systematically mapped.136 Frozen tissue sections are prepared, and close to 100% of the peripheral and deep margins are examined. If carcinoma is detected at the margin, another horizontal layer of tissue is excised from the area and examined microscopically. The process is repeated until no cancer is detected at the margin. With Mohs micrographic surgery, both superior histopathologic confirmation of tumor removal and tissue conservation are accomplished. Frederic Mohs, who first described this method in 1941,137 initially proposed that zinc chloride paste be applied to the skin as a fixative 24 hours prior to excision and sectioning of tissue (fixed-tissue technique). Later, the fixative was omitted (fresh-tissue technique) to do away with the pain associated with tissue fixation, allow multiple stages of surgery to be performed in one day, and leave a defect that could be repaired immediately if desired.138 Mohs micrographic surgery leaves a tissue defect that may require surgical repair; however, it is a highly effective approach for high-risk, incompletely excised, and recurrent skin cancers, as well as tumors located in areas where tissue conservation is of functional and cosmetic importance. Contraindications to Mohs surgery include cancers with discontiguous growth and difficult to diagnose features on frozen-section pathologic examination. Rowe and colleagues have reported 5-year cure rates of 99% and 97% with Mohs micrographic surgery for basal and squamous cell carcinomas respectively.98,139 Squamous cell carcinomas with perineural invasion should be treated with Mohs micrographic surgery and postoperative radiation therapy; for basal cell carcinomas with perineural invasion, post-Mohs micrographic surgery radiation therapy may be considered.74,75

Like Mohs micrographic surgery, radiation therapy constitutes an effective form of treatment for recurrent carcinomas as well as large carcinomas involving the forehead or scalp. Radiation therapy is also generally recommended for carcinomas located in the central face and is particularly well suited to the treatment of cancers (≥0.5 cm) involving the ears, eyelids, tip or ala of the nose, or commissure of the lips because these sites can be difficult to reconstruct surgically. Advantages of radiation therapy are that the treatment is noninvasive, relatively painless, and, for the sites outlined earlier, less expensive than Mohs micrographic surgery followed by reconstructive surgery. Excellent rates of disease control and cosmetic outcomes can be attained with careful attention to patient selection and radiation technique.140–143 Although morpheaform basal cell carcinomas normally are not managed with radiation therapy because the margins are frequently difficult to assess clinically, they are radioresponsive. When wide margins have been provided (see the section on field size), local control has been achieved with radiation therapy in patients who declined Mohs micrographic surgery.144–145

Indications for Postoperative Radiation Therapy

Studies with a minimum follow-up period of 5 years indicate that approximately one third of basal cell carcinomas that extend to the margin of resection ultimately recur.146–149 Consequently, the management of a positive margin is somewhat controversial. Because it may be difficult to detect early recurrences in cases in which a basal cell carcinoma extends to the deep margin and the area is fibrotic from prior treatment, where grafts have been used to close a surgical defect, or where close follow-up will not be possible, immediate retreatment with surgical excision, Mohs micrographic surgery, or radiation therapy should be considered.150–151 In cases involving a graft, radiation therapy should not be initiated until a good “take” has occurred, which usually requires 3 to 4 weeks. In addition, a treatment schedule that employs a relatively large number of fractions, such as in Table 66-2, should be used. The entire graft should be included in the target volume (see the section on Field Size). In a study by Wilder and colleagues,144 all 21 basal cell carcinomas that extended to the surgical margin were controlled with radiation therapy. Immediate retreatment, either with surgery or radiation therapy, should be performed when a squamous cell carcinoma extends to the surgical margin because this type of cancer is more likely to recur locoregionally than basal cell carcinoma.

The data on adjuvant radiation therapy in the setting of perineural invasion is controversial.152 Because the presence of perineural invasion in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the skin is often associated with aggressive clinical behavior, an increased risk of recurrence, and a poorer prognosis, postoperative radiation therapy is generally recommended. Among 135 patients treated at the University of Florida by surgery followed by postoperative radiation therapy, local control rates were 87% and 55% for those with microscopic and macroscopic perineural invasion, respectively.153 Although a combined-modality approach is generally preferred in this setting, the extent to which radiation therapy improved outcomes, particularly among those with microscopic perineural invasion, remains to be debated. When perineural invasion is suspected for patients with disease involving the head and neck, MRI of the base of skull and regional lymph nodes should be considered to fully evaluate the extent of possible spread and to assess the status of the regional lymph nodes.

Radiation also plays an important role in the management of parotid area metastasis from cutaneous skin cancer. Because the lymph nodes in and around the parotid gland receive most of the lymphatic drainage from the facial skin and scalp, they are the site most commonly involved when skin cancer from the head and neck metastasizes to the regional lymph nodes. Taylor and colleagues reported local control rates of 63% among patients treated with surgery alone compared with 89% for patients treated by surgery and postoperative radiation therapy.154 Another study from the University of California, San Francisco, demonstrated that inclusion of the ipsilateral N0 neck decreased the incidence of subsequent nodal failures from 50% to 0%.155

Techniques of Radiotherapy

Energy and Filtration

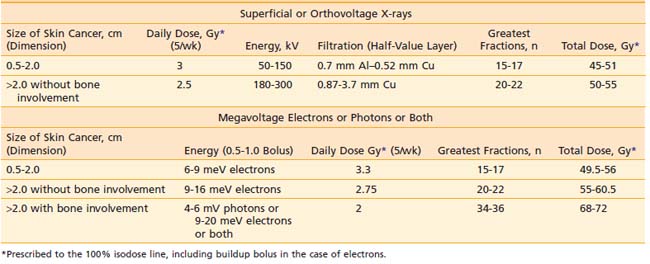

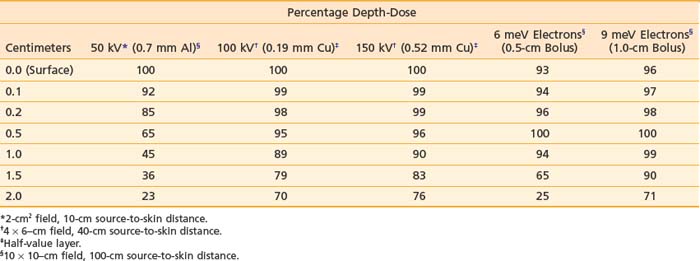

Orthovoltage x-rays and electron beams are most commonly used in the treatment of skin cancer. The technique used is determined by the size, depth, and anatomic location of the lesion. The quality of the radiation should be selected based on a review of the depth-dose characteristics of the available modalities (Table 66-3).

Table 66-3 Central Axis Percentage Depth-Doses as a Function of Energy, Buildup Bolus Thickness, Filtration, Field Size, and Source-to-Skin Distance

Based on articles involving superficial (50 to 150 kV) and orthovoltage (160 to 300 kV) x-rays156 that were published in the 1950s and 1960s,157–159 a number of authors have suggested that radiation therapy is contraindicated for carcinomas involving bone or cartilage because of the excessive risk of osteoradionecrosis and radiochondritis. However, more recent literature indicates that properly fractionated radiation therapy can be used in these cases and, in fact, is often the treatment of choice with or without surgery because the risk of radiation-induced complications is low when careful attention is paid to technical factors.143,160

Most carcinomas of the skin can be cured with superficial or orthovoltage x-rays or megavoltage electrons. Advantages of superficial or orthovoltage x-rays are that they require less of a margin on the skin surface around a carcinoma and are less expensive than electrons. In addition, when carcinomas of the eyelid are treated with orthovoltage x-rays rather than 6 meV electrons, the cornea receives a lower dose of radiation.161

Because irradiation of deep subcutaneous tissue increases the likelihood of conspicuous scarring, energy selection is important. The most commonly used peak superficial and orthovoltage x-ray energies are 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 kV. With superficial and orthovoltage x-rays (and megavoltage electrons), an energy should be selected such that the 90% depth-dose encompasses the target volume (see Table 66-3). Because most basal cell carcinomas extend to a depth of 2 to 5 mm,162 50-kV x-rays have been recommended in the dermatology literature. As presented in Table 66-4, a typical 50-kV beam delivers 85% of the surface dose at a depth of 2 mm and only 65% of the surface dose at a depth of 5 mm. Consequently, soft x-ray (50-kV) beams should be used only with very superficial lesions such as small eyelid tumors.163

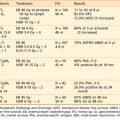

Table 66-4 Five-Year Local Control Rates for Previously Treated Basal Cell Carcinoma

| 5-Year Local Control, % Treatment Modality | (Controlled/Treated, n/n) |

|---|---|

| Mohs micrographic surgery | 94 (2841/3009) |

| Radiation therapy | 87 (204/234) |

| Cryotherapy | —* |

| Surgical excision | 83 (431/522) |

| Curettage and electrodesiccation | 60 (69/115) |

* The 5-year results have not been published for cryotherapy. The weighted mean of the local control rates for studies with fewer than 5 years of follow-up is 87% (227/261).

Data from Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr: Mohs’ surgery is the treatment of choice for recurrent (previously treated) basal cell carcinomas, J Dermatol Surg Oncol 15:424, 1989.

The roentgen-to-rad conversion (f) factor, relates exposure in air to the absorbed dose of radiation in tissue.156 The f factor depends on both radiation energy and tissue composition. For a tissue with an atomic number much greater than that of air, the f factor changes significantly as the radiation energy decreases to less than 300 kV (e.g., for compact bone, f factors equal 0.94 at 4 mV and 300 kV compared with 1.45 at 100 kV, whereas for skin, f factors equal 0.96 at 4 mV and 300 kV compared with 0.94 at 100 kV164). At energies below 300 kV, the dose of radiation in a tissue with a high atomic number (e.g., compact bone) is greater than the dose in a tissue with a low atomic number (e.g., skin). As a result, if a carcinoma invades bone, electrons or megavoltage photons or both provide a more homogeneous dose of radiation in the target volume than superficial or orthovoltage x-rays.

Filtration “hardens” a superficial or orthovoltage x-ray beam, meaning it removes low-energy x-rays,156 thereby reducing the dose in bone. The degree of hardening or beam quality can be expressed in terms of the half-value layer (HVL), or the thickness of a material that, when introduced into the path of an x-ray beam, reduces the exposure rate by one half. With older superficial and orthovoltage x-ray machines, one can select from among several filters after deciding on an energy. In general, one should select the thickest filter that will provide a dose rate greater than 0.5 Gy per minute. Aluminum is commonly used to filter 50- to 100-kV x-rays; copper with or without tin, both of which have a higher atomic number, is used to filter higher energies (1 mm of copper is approximately equal to 16 mm of aluminum).165 Typical HVLs for 50-, 100-, and 150-kV x-rays are presented in Table 64-3. HVLs (and percentage depth-doses) for 75-, 180-, 200-, 250-, and 300-kV x-rays are presented in articles by Scrimger and Connors,166 Niroomand-Rad and colleagues,167 and McCullough.165 More recently, manufacturers have provided only one filter for each x-ray energy to ensure that proper filtration is used.

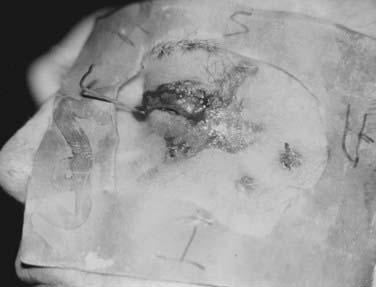

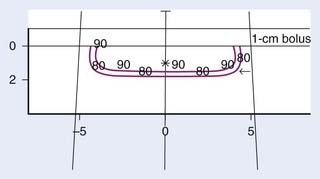

With electrons, there is a rapid falloff of the dose with depth (see the percentage depth-doses for 6 meV electrons in Table 66-3), allowing one to spare underlying tissue. When a skin cancer has invaded bone, megavoltage photons can provide a relatively homogeneous dose in the target volume. Consequently, with carcinomas that extensively invade soft tissue or bone or both, electrons or megavoltage photons or both are preferable to orthovoltage x-rays. Based on the skin-sparing property of electrons and megavoltage photons, 0.5- to 1.0-cm buildup bolus should be used.156 Skin bolus applied over an uneven surface area can also assist in improving electron dosimetry (Fig. 66-4).

There is little variation in the dose of radiation delivered to cartilage by superficial or orthovoltage x-rays or megavoltage electrons or photons or both (for cartilage, the f factor equals 0.92 at both 4 mV and 100 kV).168 Chondritis is rare after the administration of daily doses of radiation of 3 Gy or less and suggests tumor recurrence.143,160,169,170

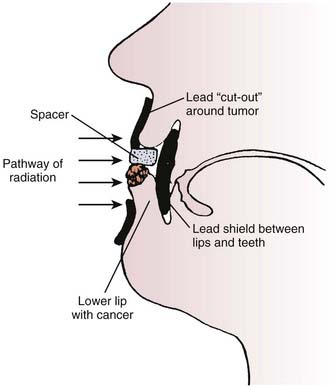

To minimize normal-tissue toxicity, underlying structures such as the lens, cornea, nasal septum, and teeth should be protected by placing a lead shield under the eyelids (Fig. 66-5), over or in the nasal cavity (Fig. 66-6), or under the lips (Fig. 66-7). When an eyelid cancer is treated, a thin dental acrylic or wax coating should be applied to the superficial surface of the lead shield.156 When skin cancers at other sites are treated, a thicker coating (e.g., 2 mm of aluminum) should be applied to the superficial surface of the lead shield.156 The dental acrylic, Teflon, wax, or aluminum coating absorbs backscattered photons or electrons, thereby reducing the conjunctival or mucosal reaction.

FIGURE 66-7 • Diagram illustrating the proper setup for treating a carcinoma of the lower lip with superficial or orthovoltage x-ray therapy. A lead cutout should be placed around the tumor and a lead shield coated with wax or aluminum (see the section on Energy and Filtration) should be inserted between the lips and teeth.

(From Buschke F, Parker RG: Radiation therapy in cancer management. New York, 1972, Grune & Stratton, p 71.)

Time, Dose, and Fractionation

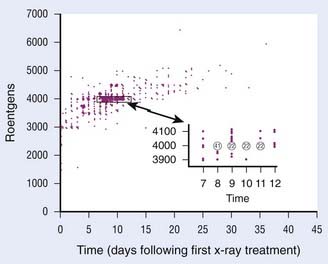

Time-dose relationships in skin cancer have been studied extensively. In his classic paper, Strandqvist171 examined skin reactions for various fractionation schemes. His work was further expanded by Von Essen,172 who applied isoeffect lines for 99% probability of cure versus 3% probability of skin necrosis and related these findings to the dose per fraction and total dose. He also demonstrated that larger volumes of tissue do not tolerate radiation as well and therefore require smaller daily doses. Total superficial and orthovoltage x-ray doses that resulted in an uncomplicated cure of basal and squamous cell carcinomas are presented in Fig. 66-8. Ellis,173 with the introduction of the nominal standard dose system, emphasized the importance of separating out overall time from the number of fractions. The nominal standard dose system allows one to select time-dose relationships that will produce similar acute skin reactions, provided that the range of time and difference in the number of fractions are not too great.174

Many studies have demonstrated that the late effects of radiation therapy on the skin (e.g., telangiectasia, atrophy, and hypopigmentation) can be minimized with the use of a more fractionated course of treatment. Turesson and Notter175,176 examined late radiation changes of the skin in women with breast cancer treated to the internal mammary nodes. He observed less severe telangiectasia in patients who received five as opposed to one or two fractions each week. Traenkle and Mulay177 studied the incidence of necrosis in 1751 patients with basal and squamous cell carcinomas treated with five different 100-kV (1.5-mm aluminum HVL) dose schedules. Patients treated with four or five 10 Gy fractions had a markedly higher incidence of necrosis (14% at  years) than those who received nine 5 Gy fractions, thirteen 4 Gy fractions, or eighteen 3 Gy fractions (3% at

years) than those who received nine 5 Gy fractions, thirteen 4 Gy fractions, or eighteen 3 Gy fractions (3% at  years). Petrovich and colleagues178 reported excellent cosmetic and functional results after the treatment of carcinomas of the skin with daily doses of 3 Gy or less (most of the 896 patients were managed with superficial x-rays). Because radiation therapy is typically recommended for carcinomas involving the pinna of the ear, eyelid, tip or ala of the nose, or lips based on its ability to provide excellent cosmetic and functional results, it seems prudent to select a time-dose relationship that will give not only the highest chance for tumor control but also the best cosmetic and functional outcome. To do otherwise may negate the advantage of radiation therapy over surgery. Based on this premise, the time-dose relationships in Table 66-2 have been formulated. Doses in this table are prescribed to the 100% isodose line, including buildup bolus in the case of electrons.

years). Petrovich and colleagues178 reported excellent cosmetic and functional results after the treatment of carcinomas of the skin with daily doses of 3 Gy or less (most of the 896 patients were managed with superficial x-rays). Because radiation therapy is typically recommended for carcinomas involving the pinna of the ear, eyelid, tip or ala of the nose, or lips based on its ability to provide excellent cosmetic and functional results, it seems prudent to select a time-dose relationship that will give not only the highest chance for tumor control but also the best cosmetic and functional outcome. To do otherwise may negate the advantage of radiation therapy over surgery. Based on this premise, the time-dose relationships in Table 66-2 have been formulated. Doses in this table are prescribed to the 100% isodose line, including buildup bolus in the case of electrons.

The relative biologic effectiveness (RBE) of superficial or orthovoltage x-rays is 10% to 15% higher than the RBE of megavoltage electrons or photons.179,180 One way to account for this difference is to administer daily and total megavoltage doses that are 10% to 15% higher than the corresponding superficial or orthovoltage x-ray doses (see Table 66-2). Prescription of electron doses to 90% versus Dmax for x-rays is another way to account for the RBE difference between the two beam qualities.

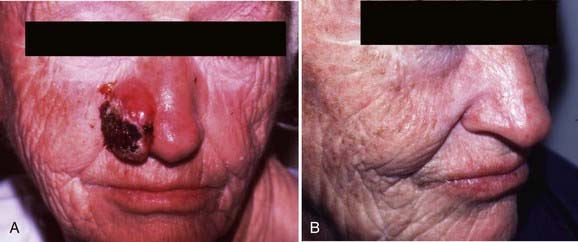

Field Size

Radiation has the advantage of being able to treat clinically detectable and subclinical disease as well as a margin of normal tissue without the creation of a tissue defect. With careful attention to technique and patient selection, radiation therapy can produce high cure rates (see the section on Results) with excellent cosmetic and functional results (Fig. 66-9 and Fig. 66-10).

When field sizes for superficial and orthovoltage x-rays and megavoltage electrons are discussed, it is important to distinguish the target volume from the treatment volume. The target volume consists of the palpable carcinoma and any adjacent tissue that may be infiltrated by carcinoma, taking prior treatment and histologic subtype into account. The treatment volume consists of an additional margin around the target volume that must be provided to allow for physical limitations of the technique.156

The margin of normal-feeling tissue included in the target volume is usually 0.5 to 1.0 cm for skin cancers of 2.0 cm or less and 1.5 to 2.0 cm for larger cancers. At least a 0.5-cm margin on the suspected depth of invasion should be included in the target volume. Because recurrent and morphea basal cell carcinomas tend to infiltrate more widely, the margins should be approximately 0.5 cm more generous to avoid a recurrence at the margin of the field.181,182 As the field size decreases, the flatness of a superficial or orthovoltage x-ray beam decreases slightly.167 With megavoltage electrons, there is lateral constriction of the isodose curves in the deep portion of the target volume (Fig. 66-11). As the field size decreases, the lateral constriction of the isodose curves becomes more pronounced.156 Consequently, if electrons are used rather than superficial or orthovoltage x-rays, a 0.5-cm-wider margin should be provided at the skin surface (i.e., the treatment volume should be larger). In one study of basal and squamous cell carcinomas, the local control rates achieved with electrons were less than the local control rates achieved with superficial x-rays.183 In this study, the use of buildup bolus with electrons varied over time, and it is not stated whether the lateral constriction of electron isodose curves in the deep portion of the target volume and the decreased RBE of electrons relative to superficial x-rays were accounted for. The authors conclude that the poorer results obtained with electrons may have been “due to technical factors such as the use of bolus and the collimation of field sizes.”183 In most studies, equivalent results have been achieved with either superficial x-rays or megavoltage electrons.140,184,185

Well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas are generally treated in the same manner as basal cell carcinomas. However, in the case of high-risk squamous cell carcinomas (see the section on Routes of Spread), consideration should be given to the use of a 2.0-cm margin around the primary tumor186 and the inclusion of regional lymph nodes (e.g., cervical or parotid nodes) in the target volume.

When perineural invasion is present, skin cancers typically extend 1 to 2 cm along the nerve sheath,187 but may occasionally extend up to 14 cm.77 Consequently, the involved nerve retrograde toward the skull base foramen should be included in the target volume when perineural invasion is noted.74,75

Brachytherapy

There has been a decline in the treatment of skin cancer with interstitial brachytherapy and radioactive molds over the past few decades. Several reasons account for this, including the widespread availability of megavoltage electrons and the ability to deliver megavoltage electrons on an outpatient basis.188 Although skin cancers today are typically treated with external-beam radiation therapy, interstitial brachytherapy is a treatment option for carcinomas smaller than 4 cm (larger carcinomas are technically difficult to implant).189,190 In general, local anesthesia and systemic sedation are adequate for a skin cancer implant,189 although some clinicians prefer to administer a regional nerve block.190 Carcinomas that are 0.75 cm thick or less can be treated with a single-plane implant.189 To improve the dose homogeneity, templates with predrilled, evenly spaced holes can be used to guide needle insertion. Steel hypodermic needles (e.g., 19.5-gauge [0.05 cm inner diameter]) or plastic tubes (e.g., 18-gauge angiocaths) can be used.188–190 The optimal spacing between needles is typically 1.0 to 1.5 cm.189,90 Two to five hypodermic needles or plastic tubes are usually required, depending on the size of the carcinoma. Stabilizing bars are commonly applied to the ends of needles to maintain parallelism during treatment. Plain radiographs (orthogonal views) are taken so that computerized treatment planning can be performed. In the patient’s shielded hospital room, iridium-192 is afterloaded and buttons are applied to secure the iridium-192 in place. When patients are treated with interstitial brachytherapy alone, the minimal tumor dose should be between 55 and 70 Gy (filtration by steel needles reduces the dose by less than 1%, and no correction is required).188–190 Continuous low-dose-rate (LDR) irradiation is delivered over 5 to 8 days, depending on the activity of the iridium-192.

Skin cancers of 0.4 cm in thickness or less in regions that tolerate radiation poorly, such as the dorsum of the hand or the shin, may be treated with radioactive surface molds because the radiation dose falls off rapidly outside the target volume. Radium-226, radon-222, gold-198, and iridium-192 have typically been used in surface molds. Based on radiation safety concerns, gold-198 and iridium-192 have been used more often in recent years. Afterloading techniques for iridium-192 molds have been described in detail.191,192 In summary, a treatment plan is constructed wherein iridium-192 seeds are positioned in a tissue-equivalent (e.g., wax) mold 1 cm from the surface of the skin to improve dose homogeneity. In the patient’s shielded hospital room, 17-gauge hypodermic needles are passed through the mold. An iridium-192 ribbon is threaded into each hollow needle, the needles are removed, leaving the ribbons in place, and the mold is secured to the carcinoma with Micropore tape or a Velcro strap. For small, superficial carcinomas, Ashby and colleagues193 recommend a minimal target dose of 40 Gy over 4 days, corresponding to a surface dose of 47 to 62 Gy.193 High dose rate delivered in multiple-daily or twice-daily fractions may be considered for replacement of LDR.

Treatment Results

Rowe and colleagues194 reviewed the literature on previously untreated basal cell carcinomas and reported 5-year local control rates of 90% (2342 of 2606) for surgical excision, 91% (4285 of 4695) for radiation therapy, 92% (3299 of 3573) for curettage and electrodesiccation, 93% (249 of 269) for cryotherapy, and 99% (7597 of 7670) for Mohs micrographic surgery. Rowe and colleagues139 also extensively reviewed the literature on recurrent basal cell carcinomas. Their findings, which have been updated with regard to radiation therapy,140 are presented in Table 66-4. The 5-year local control rate for recurrent basal cell carcinomas managed with radiation therapy is 87% (204 of 234), which compares favorably with the results obtained with cryotherapy (<87%), surgical excision (83%; 431 of 522), and curettage and electrodesiccation (60%; 69 of 115).

Fitzpatrick and colleagues195 reviewed 1166 eyelid carcinomas treated with radiation therapy. The 5-year local control rates were 95% for basal cell carcinomas and 93% for squamous cell carcinomas. The overall complication rate was 10%; however, most of the “complications” apparently represented normal tissue damage by the carcinomas before treatment, and less than half the cases were considered serious. In general, patients judged the cosmetic results to be excellent.

Petrovich and colleagues196 reviewed 646 patients with carcinomas of the eyelids, ear, and nose. The 5-year actuarial local control rates achieved with radiation therapy were 93% for 464 basal cell carcinomas, 90% for 67 basosquamous cell carcinomas, and 83% for 115 squamous cell carcinomas. Including salvage treatment, the local control rates were 99% for basal cell carcinomas, 95% for basosquamous carcinomas, and 94% for squamous cell carcinomas. The 5-year local control rates obtained with radiation therapy were 93% for carcinomas less than 2 cm in the greatest dimension, 63% for carcinomas 2 to 5 cm in the greatest dimension, and 50% for advanced carcinomas. Bone or cartilage involvement was present in 23 patients, in whom the 3-year actuarial control rate was 83% with radiation therapy alone. No bone, cartilage, or soft tissue necrosis developed, and no serious complications were observed.

Petrovich and colleagues143 reviewed an additional three basal and 247 squamous cell carcinomas of the lip treated over a 22-year period and reported an overall crude local control rate of 89%. The local control rates were 94% for AJCC stages I and II (221 patients), 90% for stage III (10 patients), and 47% for stage IV (19 patients). In 227 patients without nodal involvement, the local control rate was 93%. Nodal involvement was present in 23 patients; in these individuals, the control rate was 52%. The cosmetic and functional results were considered excellent in patients with smaller carcinomas and those who received daily superficial x-ray doses of 3 Gy or less. Five patients (2%) developed necrosis of the mandible; all of them had massive tumor involvement of the mandible before radiation therapy.

Locke and colleagues183 analyzed 531 basal and squamous cell carcinomas treated with radiation therapy. For previously untreated cancers less than 2 cm, the local control rates were 96% (190 of 197) for basal cell carcinomas and 95% (39 of 41) for squamous cell carcinomas. For previously untreated cancers measuring 2 to 5 cm, the local control rates were 90% (36 of 40) and 86% (18 of 21), respectively, for basal and squamous cell carcinomas. For previously untreated cancers greater than 5 cm, 94% (15 of 16) of the basal cell carcinomas were controlled compared with 86% (6 of 7) of the squamous cell carcinomas. Recurrent cancers in all categories had slightly lower control rates. The cosmetic results were evaluated in 435 patients and judged to be good to excellent in 92%. As with the local control rates, the quality of the cosmetic results depended on the size of the carcinoma, with 99% of tumors less than 1 cm and 92% of tumors 1 to 3 cm, showing excellent or good cosmesis. Overall, 5% of the patients developed soft tissue necrosis. The authors point out that with attention to additional technical details including prescription depth, bolus, and margins, patients treated with electrons did not have higher local failure rates as compared with patients treated with superficial radiation therapy.

Treatment Recommendations by Specific Anatomic Site

Dorsum of the Hand

The most common cancer of the dorsum of the hand is squamous cell carcinoma.197 Small cancers at this site are typically treated with cryotherapy, curettage and electrodesiccation, surgical excision, or Mohs micrographic surgery. In general, cancers involving the dorsum of the hand are not managed with radiation therapy because repeated trauma results in a higher risk of necrosis, although carcinomas of 0.4 cm or less in thickness have been successfully treated with radioactive surface molds (see the section on brachytherapy).193,198 Mohs micrographic surgery is generally the preferred method of treatment for carcinomas greater than 2 cm.

Eyelid

Radiation therapy represents an effective method of treating eyelid carcinomas, with good cosmetic and functional results and a low risk of complications.199 With orthovoltage x-rays, less of a margin needs to be provided at the skin surface, the cornea receives a lower dose of radiation, and the cost of treatment is less than with electrons. For carcinomas measuring 0.5 to 2.0 cm in the greatest dimension, the delivery of a total dose of 48 Gy in 16 fractions over  weeks using 100-kV x-rays and a 0.19-mm copper HVL (or similar technique) is recommended. Patients may develop mild conjunctivitis from the daily installation of the eye shields (see Fig. 66-4) and the acute effects of radiation on the conjunctiva. A decongestant solution or artificial tear eye ointment (Lacri-Lube) helps to relieve the burning and pruritus. Bacterial conjunctivitis may be treated with 10% sodium sulfacetamide (Sodium Sulamyd) ophthalmic ointment four times daily and at bedtime. Although the eyelashes in the irradiated area fall out and do not grow back, this does not cause functional problems. Large carcinomas may produce ectropion, and carcinomas involving the lower eyelid, inner canthus, punctum lacrimale, or nasolacrimal duct may produce epiphora.163 Ectropion or epiphora may also develop as a complication of treatment, regardless of the modality selected. These complications improve in approximately one half of patients who undergo corrective surgery.195 Radiation-induced cataracts used to develop after radium plaque irradiation because it was not possible to shield the lens from the high-energy gamma-rays. However, with modern treatment techniques (e.g., superficial x-ray therapy with a lead shield placed under the eyelids), cataracts are uncommon. Surgery is preferred for carcinomas less than 0.5 cm in the greatest dimension and may be used to salvage radiation failures.195

weeks using 100-kV x-rays and a 0.19-mm copper HVL (or similar technique) is recommended. Patients may develop mild conjunctivitis from the daily installation of the eye shields (see Fig. 66-4) and the acute effects of radiation on the conjunctiva. A decongestant solution or artificial tear eye ointment (Lacri-Lube) helps to relieve the burning and pruritus. Bacterial conjunctivitis may be treated with 10% sodium sulfacetamide (Sodium Sulamyd) ophthalmic ointment four times daily and at bedtime. Although the eyelashes in the irradiated area fall out and do not grow back, this does not cause functional problems. Large carcinomas may produce ectropion, and carcinomas involving the lower eyelid, inner canthus, punctum lacrimale, or nasolacrimal duct may produce epiphora.163 Ectropion or epiphora may also develop as a complication of treatment, regardless of the modality selected. These complications improve in approximately one half of patients who undergo corrective surgery.195 Radiation-induced cataracts used to develop after radium plaque irradiation because it was not possible to shield the lens from the high-energy gamma-rays. However, with modern treatment techniques (e.g., superficial x-ray therapy with a lead shield placed under the eyelids), cataracts are uncommon. Surgery is preferred for carcinomas less than 0.5 cm in the greatest dimension and may be used to salvage radiation failures.195

Lip

The most common cancers of the upper and lower lips are basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, respectively. These carcinomas often involve the vermilion border between the red area of the lips and the surrounding facial skin and may be treated with surgical excision, radiation therapy, or Mohs micrographic surgery. When external-beam radiation therapy is administered, a lead shield should be placed beneath the lip to reduce the absorbed dose of radiation in the teeth and mandible (see Fig. 66-6). For carcinomas measuring 0.5 to 2.0 cm in the greatest dimension, the delivery of a total dose of 48 Gy in 16 fractions over  weeks using 150-kV x-rays and a 0.52-mm copper HVL (or similar technique) is recommended. If interstitial brachytherapy alone is used, a gauze roll containing a 2-mm lead shield should be placed under the lip to minimize the absorbed dose of radiation in the teeth and mandible.190 From 55 to 70 Gy should be delivered over 5 to 8 days.190,191 Carcinomas greater than 4 cm can be successfully treated with the delivery of external-beam radiation therapy to the lip, chin, and neck to a total dose of 50 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks followed by a 30 to 40 Gy iridium-192 interstitial brachytherapy boost over 3 to 4 days.170,190 Rubber tubing containing an iridium-192 ribbon may be placed horizontally on top of a lower lip carcinoma to improve the dose distribution.170 If a squamous cell carcinoma is poorly differentiated, recurrent, more than 3 cm in the greatest dimension, or 4 mm in thickness, the submandibular and upper jugular lymph nodes should be included in the target volume.

weeks using 150-kV x-rays and a 0.52-mm copper HVL (or similar technique) is recommended. If interstitial brachytherapy alone is used, a gauze roll containing a 2-mm lead shield should be placed under the lip to minimize the absorbed dose of radiation in the teeth and mandible.190 From 55 to 70 Gy should be delivered over 5 to 8 days.190,191 Carcinomas greater than 4 cm can be successfully treated with the delivery of external-beam radiation therapy to the lip, chin, and neck to a total dose of 50 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks followed by a 30 to 40 Gy iridium-192 interstitial brachytherapy boost over 3 to 4 days.170,190 Rubber tubing containing an iridium-192 ribbon may be placed horizontally on top of a lower lip carcinoma to improve the dose distribution.170 If a squamous cell carcinoma is poorly differentiated, recurrent, more than 3 cm in the greatest dimension, or 4 mm in thickness, the submandibular and upper jugular lymph nodes should be included in the target volume.

Nose and Ear

Similar results can be achieved with superficial x-rays, electrons, or interstitial brachytherapy.185 A wax- or aluminum-coated lead strip should be placed in the nasal cavity to reduce the mucosal reaction. When carcinomas involving the ala of the nose are treated, the nasolabial fold should be included in the target volume (see Fig. 66-5). Wax can be used as bolus on irregular surfaces to improve the dose homogeneity in the target volume. For carcinomas measuring 0.5 to 2.0 cm in the greatest dimension, the delivery of a total dose of 52.8 Gy in 16 fractions over  weeks using 6 meV electrons and 0.5-cm buildup bolus (or similar technique) is recommended.

weeks using 6 meV electrons and 0.5-cm buildup bolus (or similar technique) is recommended.

Prevention

Patients should be advised to avoid peak, mid-day UV exposures and wear a wide-brimmed hat and other protective clothing, as well as a broad-spectrum (UVA, UVB) sunscreen with a sun protection factor of at least 30 when outdoors. Regular follow-up is important so that potential precursor lesions such as actinic keratoses can be treated and lesions suspicious for nonmelanoma skin cancer evaluated. All organ transplant patients should receive education about their increased risk of skin cancer and appropriate sun protection practices both before and after their transplant, and be followed closely with self- and physician-guided skin examinations.46 Patients with HIV should be similarly counseled regarding sun protection practices and the need for routine skin examination.52

Topical retinoids may improve the appearance of photo-damaged skin,200 and be employed in the management of patients with multiple actinic keratoses.201 Successful chemoprophylaxis with oral retinoids has been reported in patients with basal cell nevus syndrome, xeroderma pigmentosum, and the organ transplant population, but long-term therapy is necessary,202–204 and may be limited by associated side effects (mucocutaneous xerosis, alopecia, musculoskeletal symptoms, increased triglyceride and cholesterol profiles, and liver function abnormalities).205,206 In organ transplant recipients, reduction of immunosuppressive therapy has been associated with a decrease in the number of new skin cancers and an improved outcome in preexisting carcinomas.207 Another strategy may be conversion of the immunosuppressive regimen to sirolimus, a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, which has been shown to reduce the number of new malignancies following organ transplantation.208 A number of other potential chemopreventative agents continue to be investigated, including difluoromethylornithine; T4 endonuclease V; polyphenolic antioxidants isolated from green tea and grape seed extract; silymarin; isoflavone genistein; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; curcumin; lycopene; vitamin E; beta-carotene; and selenium.206

Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma (previously known as trabecular carcinoma or primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin) is a rare, clinically indistinct, but aggressive neoplasm that was first described by Toker in 1972.209 A newly described polyomavirus has been found in association with Merkel cell carcinoma.210 The majority of Merkel cell carcinomas are located on the head and neck, followed by the extremities and trunk. Like other carcinomas of the skin, Merkel cell carcinomas usually develop in individuals who are in their sixth to eighth decade of life. Both UV radiation and immune suppression appear to be predisposing factors.211 Merkel cell carcinoma presents nonspecifically as a firm nodule that is pink to red, or violaceous that varies in diameter from a few millimeters to several centimeters and often grows rapidly with ulceration (Fig. 66-12). Although the majority of Merkel cell carcinomas present with clinically localized disease, this is a biologically aggressive tumor that can recur locally and spread quickly to regional and distant sites.212–214 The clinical differential diagnosis includes inflamed cyst, hemangioma, poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, angiosarcoma, adnexal carcinoma, lymphoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and metastatic cancers.

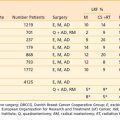

Although the natural history of Merkel cell carcinoma is variable, prognosis is best associated with stage at presentation.215,216 Several staging systems, including guidelines by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network as well as soon-to-be released recommendations from the AJCC, offer guidance for the management of Merkel cell carcinoma.217 Surgical excision with negative margins is generally recommended as a first-line approach, and sentinel lymph node biopsy is increasingly being recognized as an important prognostic tool.218–221 Merkel cell carcinomas have traditionally been treated with wide local excision, which results in locoregional recurrences in 73% (43 of 59) of patients.213 Several authors have reported their experience with Mohs surgery, which compares favorably with standard excision for the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma.222,223 Locoregional control appears to be improved in patients treated with surgery and postoperative radiation therapy.224–230 Because patients are usually referred for radiation therapy because they are judged to be at high risk for recurrence, it is unlikely that the individuals who were managed with surgery and postoperative radiation therapy in these studies had a more favorable prognosis than those who were managed with surgery alone.

Use of a wide margin in the radiation portals is important in achieving locoregional control (Fig. 66-13). Morrison and colleagues reported that 80% of patients (4 of 5) developed regional recurrences when treated with small fields encompassing only the primary tumor bed.225 Similarly, Goepfert and colleagues reported that 67% of patients (8 of 12) without clinical evidence of lymph node metastases developed regional metastases when the draining lymph nodes were not electively irradiated.231 Consequently, inclusion of the regional lymphatics in continuity with the primary tumor bed is recommended.

Doses of 45 to 50 Gy (or greater) are generally recommended for Merkel cell carcinoma. Pacella and colleagues reported that with a median follow-up of 14 months, in-field control was maintained in 13 of 13 patients with no measurable disease and 22 of 23 patients with measurable disease after the administration of a median dose of 45 Gy in 20 fractions over a 4-week period.232 In the study by Goepfert and colleagues, in-field control was maintained in 10 of 10 patients with macroscopic disease after the administration of 50 to 75 Gy using conventional fractionation with or without an interstitial boost.231 As a result, we recommend irradiation of the operative bed and regional lymphatics to a total dose of 50 to 55 Gy at 1.8 to 2 Gy per day in the adjuvant setting. In patients with gross disease, a boost to bring the total dose to 60 to 65 Gy is recommended. In an effort to improve locoregional control, aggressive surgery has been advocated by some.233 However, because radiation therapy is effective at sterilizing subclinical disease, the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma with limited surgery (e.g., an excisional biopsy) and immediate postoperative radiation therapy can obviate the need for extensive reconstructive procedures.234,235 Mortier and colleagues demonstrated similar rates of recurrence and no differences in overall or disease-free survival between patients treated by radiation therapy alone and those treated by wide excision followed by postoperative radiation therapy. In addition, when the regional lymph nodes are clinically negative, they can be included in the radiation therapy portals, obviating the need for unilateral or bilateral lymph node dissections electively. Although some have suggested an orderly progression of spread from the site of origin to regional lymphatics to distant sites, the natural history remains somewhat uncertain.235,236 In the study by Pacella and colleagues, the only patient whose primary tumor was treated de novo with an excisional biopsy and radiation therapy remained disease-free 77 months later.232 Lewis and colleagues reported that the 5-year actuarial disease-free survival rate was 11% for surgery alone versus 56% for surgery and postoperative radiation therapy (P = 0.002).230 Similarly, Meeuwissen and colleagues reported that the 3-year actuarial disease-free survival rate was 0% for 38 patients treated with surgery alone versus 68% for 34 patients treated with surgery and postoperative radiation therapy.224 These results suggest that postoperative radiation therapy may be able to improve disease-free survival if it is incorporated into the initial treatment.237

A recent analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database of 1665 patients treated for Merkel cell carcinoma between 1973 and 2002 showed that the use of adjuvant radiation therapy was significantly associated with an improved survival.238 Although the survival advantage of radiation therapy was observed across all subsets, patients with primary lesions in excess of 2 cm appeared to derive the most benefit. Notably, the median survival for patients receiving adjuvant radiation therapy was 63 months compared with 45 months for those treated without radiation therapy. Although some have criticized the SEER analysis for problems related to selection bias,239 others have also similarly demonstrated that adjuvant radiation therapy is essential for optimizing outcomes in the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma.240,241

Although the predominant pattern of failure for Merkel cell carcinoma is distant, the role of chemotherapy in the upfront treatment remains controversial. In patients treated with chemotherapy alone, the partial and complete response rates have been on the order of approximately 30% and 15%, respectively.242–246 Based on the neuroendocrine origin of Merkel cell carcinoma, drugs active against small cell carcinoma of the lung (e.g., carboplatin and etoposide) have typically been administered. Because distant metastases eventually develop in a relatively large number of patients, chemotherapy has been administered in combination with surgery or radiation therapy or both in an effort to improve cure rates. In a study by George, locoregional disease responded to induction chemotherapy; however, the average duration of the responses was only 3 months.246 Similarly, Grosh and colleagues243 reported that responses to chemotherapy lasted only 2 to 4 months. A recent literature review by Tai193 revealed a total of 204 patients in the literature treated for locally recurrent or metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma.247 There was an overall 59% response rate. Results of a phase II trial from the Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group reported on 53 patients treated with adjuvant radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy (carboplatin and etoposide) for Merkel cell carcinoma. Eligibility criteria included any of the following “high-risk” features: recurrence after initial therapy, involved lymph nodes, primary tumor size greater than 1 cm, gross residual disease after surgery, or occult primary with positive lymph nodes. Overall survival at 3 years, locoregional control, and distant control were 76%, 75%, and 76%, respectively, which compared favorably with historical controls. The investigators concluded that the role of adjuvant chemoradiation for Merkel cell carcinoma warrants further investigation.248

Although it is hoped that the development of more active chemotherapeutic agents will lead to an improvement in cure rates in the future, the role of chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting for localized disease remains uncertain at present and should be made on an individualized basis. There is increasing interest in the use of sentinel node mapping in Merkel cell carcinoma to help identify which patients may benefit from chemotherapy.249–251 In the meantime, chemotherapy may offer palliation to Merkel cell carcinoma patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease, particularly those with predominantly nodal disease.

Kaposi Sarcoma

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a vascular proliferation associated with human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8). Four principal clinical variants exist: classic KS, which preferentially affects older individuals of Jewish Ashkenazi or Mediterranean descent; African endemic KS, which is lymphadenopathic, fulminant in presentation, and mainly affects children; KS in iatrogenically immunocompromised individuals; and AIDS-related epidemic KS. HIV-associated KS more often affects men who have sex with men, patients with CD4 T cell counts less than 500 cells per cubic millimeter,252 and is typically aggressive, with a median survival of 18 months if untreated.52 The introduction of antiretroviral therapy has led to a significant reduction in incidence (30%-50%), morbidity, and mortality.253,254

Antiretroviral therapy is first-line for HIV-associated KS. The response to antiretroviral therapy, which in one study occurred in 91% (18 complete and two partial responses over 40 months) of patients,255 has been shown to be associated with early start of therapy, degree of CD4 reconstitution, HIV viral load, and reduction of HHV-8 viremia.52 For aggressive or systemic KS, systemic chemotherapy is indicated; commonly used chemotherapeutics include the liposomal anthracyclines (doxorubicin and daunorubicin), the taxanes (paclitaxel and docetaxel), vinblastine, vincristine, bleomycin, and etoposide as monotherapy or in combination.256 Given the multifocality of KS, surgery is typically reserved for tissue diagnosis. Other modalities of therapy for more localized lesions include radiation therapy, PDT, cryosurgery, intralesional vinca alkaloids, intralesional interferon-alpha, intralesional human chorionic gonadotropin, and topical 9-cis-retinoic acid gel (alitretinoin).52