47 Cancer of the Male Urethra and Penis

In 2001, approximately 1.26 million people were diagnosed with cancer in the United States. Only 1200 cases were classified as cancers of the penis or male genitourinary malignancies (not bladder, ureter, prostate, or testis).1 The overall incidence based upon the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database is 0.6 per 100,000 for penile cancers and 0.3 per 100,000 for male urethral cancers. Analysis of the SEER database indicates that the incidence increases with age. Primary cancers of the penis and male urethra are extremely uncommon before the age of 55 (<1/100,000).2 Overall, primary penile and male urethral malignancies are relatively uncommon.

Primary Carcinoma of the Male Urethra

Incidence by Age

Primary carcinoma of the male urethra is extremely rare. Although cases have been reported in the literature as young as age 13, the SEER database records no cases in patients younger than the age of 20. The incidence increases with advancing age from 0.1 per 100,000 in patients ages 20 to 34, to a peak incidence of 2.6 per 100,000 in patients older than age 85.2

Etiology

No specific causal factors have been identified. However, chronic inflammation likely plays a role in the development of urethral cancers. Patients diagnosed with urethral cancers often have a history of prior sexually transmitted disease, urethritis, or urethral stricture. The incidence of urethral stricture in men diagnosed with carcinoma of the urethra ranges from 24% to 76%.3 The site of stricture is also the most likely site of malignancy.4 Approximately 10% of patients who undergo cystectomy for invasive bladder cancer also develop a urethral cancer distal to the urogenital diaphragm.

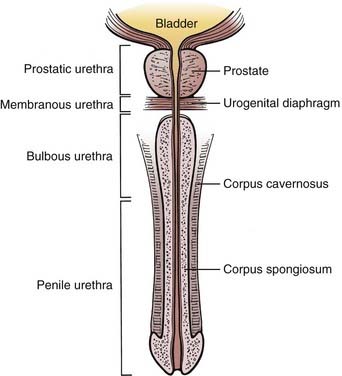

Anatomy

The male urethra, composed of a mucosa and submucosa, is approximately 20 cm in length and extends from the neck of the bladder to the external meatus of the glans penis. The prostatic urethra begins at the bladder neck and lies within the prostate. It is usually 3 cm long. It is the widest and most readily dilated portion of the urethra. It typically emerges anterior to the prostatic apex and merges with the membranous urethra. The membranous urethra lies within the urogenital diaphragm surrounded by the sphincter urethrae muscle and is the least dilatable portion of the urethra. The prostatic and membranous urethra are lined with transitional epithelium. The spongy (cavernous) urethra is enclosed in the corpus spongiosum. It is further subdivided into urethra confined by the penile bulb (bulbous urethra) and urethra distal to the bulb (penile or pendulous urethra). The narrowest portion of the urethra is the external meatus. The bulbomembranous urethra is known as the posterior urethra, while the penile urethra is referred to as the anterior urethra. Pseudostratified columnar epithelium lines the bulbous and penile urethra. Stratified squamous epithelium lines the urethra defined by the glans penis (Fig. 47-1). Numerous glands can be found in the submucosa of the urethra.

The bulbomembranous urethra is the most common site of primary malignancies (60%). Of these, 30% occur in the penile urethra, and 10% originate in the prostatic urethra.5

The anterior urethra drains into the superficial and deep inguinal lymph nodes. The bulbomembranous and prostatic urethra drain into the pelvic lymph nodes. Posterior lesions may drain to the external and internal iliac, obturator, and presacral lymph nodes.6

Natural History

Primary urethral cancers are often insidious, and symptoms are often present only when the disease is locally advanced.7 The most common presenting symptoms include a palpable urethral mass, obstructive urinary symptoms, pain, urethral fistula or abscess, hematuria, or a palpable inguinal mass.8 Because many symptoms are not specific, symptoms have been reported to be present on average 5 months before diagnosis (range, 1 day to 15 years).9 Urethral carcinoma often directly invades adjacent structures such as the corpus spongiosum and periurethral tissues. Bulbomembranous lesions can extend into the urogenital diaphragm and prostate. Invasion into the corpora cavernosa is common at the time of diagnosis. Hematogenous spread (lung, brain, bone, lymph nodes) is relatively uncommon, except in locally advanced cases.10

Prognosis of male urethral carcinomas depends primarily on location and the degree of invasion. Anterior superficial lesions generally present earlier and carry the best prognosis, while deeply invasive lesions or those located posteriorly are rarely curable. Posterior lesions tend to be deeply invasive at the time of diagnosis. Histologic findings are thought to be less significant as a prognostic factor.11

Staging

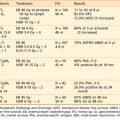

The tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system set forth by the American Joint Committee on Cancer allows data collected by both physical examination and imaging in the staging of urethral cancers. T staging is determined mainly by the depth of invasion. Regional lymph nodes are considered to be the pelvic and inguinal nodal beds. Laterality does not affect the N status (Table 47-1).12

Table 47-1 Classification of Primary Urethral Carcinomas

Rights were not granted to include this table in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book.

Management

The role of radiation therapy alone for lesions in the distal urethra is not well defined but provides the option of organ preservation. Radiation therapy alone can be curative for distal lesions, with long-term cure rates similar to those reported for surgery. The most common approach uses external-beam radiotherapy with doses between 50 and 75 Gy.13

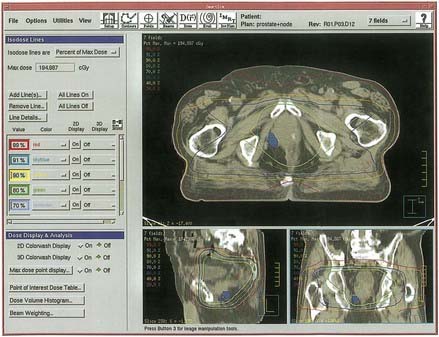

Local control may be more difficult to achieve in the bulbomembranous urethra because these lesions tend to be more locally aggressive (Fig. 47-2). Because metastasis tends to be a late event, aggressive combined approaches to local therapy should be considered.

Similar to the treatment of epidermoid lesions in other tumor sites, it is recommended to treat microscopical and subclinical disease to approximately 50 Gy. Gross tumor should be irradiated to doses up to 70 Gy in standard fractionation. The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) experience has found that those who received salvage surgery after radiotherapy fared worse than those who were treated with surgery upfront, although only six patients were reported in this category, and could represent selection bias. None of these patients received chemoradiotherapy.10

Chemoradiation has been described for both female and male urethral cancers. Case series have reported the use of fluorouracil, mitomycin, and external-beam radiation for squamous cell cancers of the male urethra.14 When chemotherapy is used in conjunction with radiation, the radiation doses have been typically lower than those with radiation alone. More modest doses (45 Gy to 55 Gy) may be sufficient in the setting of combined-modality therapy, with surgery reserved for salvage.15 Encouraging results have been reported at MSKCC for transitional-cell carcinomas in both men and women using combined-modality therapy that includes chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery.16

Chemotherapy, acting as a radioenhancer and a deterrent to distant metastasis, has been used successfully in conjunction with radiotherapy in other sites such as esophagus, head and neck malignancies, vulva, and anal canal. Failure after radiation therapy is often central, whereas surgical failures are due to an inability to achieve sufficiently wide margins. Given the rarity of urethral cancers in men, there are no reports with patients in numbers significant enough to draw conclusions. Most of the literature consists of case reports. However, in advanced tumors, the use of combined-modality therapy has yielded 60% to 100% disease-free survivals.14,17–20 Cohen et al.21 have reported the efficacy of radiation therapy (45-55 Gy/25 fractions) with concurrent 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin C in 18 men with anterior urethral cancer, using a chemotherapy regimen extensively studied for use in patients with anal canal cancer. Most patients were staged as either T3 or T4. The mean 5-year, disease-specific survival was 82.5%. Seven patients had persistent disease or recurrent disease after chemoradiation. The three nonresponders underwent salvage radical surgery, but all died of disease. Of the patients with recurrent local disease, only one died of persistant disease.21 Not only is multimodality therapy (chemoradiation and surgery) conceptually appealing in the management of urethral cancers, but initial experiences have been encouraging, and should be explored further as an aggressive management option.

Primary Carcinoma of the Penis

Incidence

Primary carcinoma of the penis is an uncommon diagnosis, accounting for less than 2% of urogenital malignancies. The SEER database has no cases of primary penile cancer in men younger than age 25. Incidence appears to be age-related. The incidence of primary penile cancer between the ages of 25 and 30 is 0.1 per 100,000 and rises to an incidence of 5.8 per 100,000 for those between the ages of 80 and 84.2

Etiology

In areas of the world where circumcision is not a common practice, primary penile cancers make up 10% to 12% of cancers diagnosed in men.22 Penile cancers are exceedingly rare in North America, but account for 45% to 76% of all genitourinary malignancies in Paraguay. In Uganda, it is the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in men.23 Overall, the incidence of primary penile cancer in the SEER database is less than 1 per 100,000. However, the lifetime risk of developing penile cancer in an uncircumcised male is estimated to be as high as 1 per 600. Also, it appears that circumcision at an early age is more likely to be protective against cancer of the penis than circumcision at the time of puberty or later.24 Penile cancer is extremely uncommon in Jewish populations that practice infant circumcision, and rarely seen in Muslims, who delay circumcision to age 3 to 13.25 Given this association with being uncircumcised, it has been postulated that smegma, which has been found to be carcinogenic in animals, may play a role in penile carcinogenesis. There is no conclusive evidence to suggest that a causative relationship exists with sexually transmitted diseases. It has also been observed to occur more commonly in the partners of women with cancer of the cervix, suggesting that human papilloma virus, which has been shown to possibly promote carcinogenesis in vitro, may be a possible causal factor.

Anatomy

The penis (see Fig. 47-1) is composed of the corpus spongiosum and two corpora cavernosa bound together in Buck fascia. The corpus spongiosum expands distally into the glans penis, which is covered by the prepuce (foreskin). The lymph from the skin of the penis, including foreskin, drains into the superficial inguinal nodes. Because of lymphatic cross drainage, penile cancers do not localize inguinal drainage to just one side. Lymphatics from the glans penis may drain to either superficial inguinal nodes or follow the lymphatics of the corpora to the iliac nodes in the pelvis. Corporal tissue drains to the deep inguinal and iliac lymph nodes.

Pathologic Conditions

Although histologic findings including malignant melanoma, lymphoma, basal cell carcinoma, and connective tissue malignancies (Kaposi sarcoma) have been noted, 95% of primary penile cancers are squamous cell carcinoma. Of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome who have Kaposi sarcoma, 18% have lesions on the penis or genitals.26

Natural History

The most common early symptoms include itching or burning under the foreskin with erythema, which may progress to areas of induration and ulceration of the glans or prepuce. Given time, these lesions progressively enlarge into palpable masses. If allowed to grow, they can progress into ulcerative masses with purulent discharge and a phimotic nonretractable, distorted prepuce. Pain may not be a dominant feature of the presentation. Occasionally, an ulcerative inguinal lymph node may be the presenting complaint. Half of patients with penile cancer present with a palpable lymph node. However, only approximately 50% of palpable lymph nodes will harbor metastatic disease, and 20% of clinically negative lymph nodes will contain disease. The most common sites of distant metastasis are the lungs, liver, and bone.27

Staging

The TNM staging system, shown in Table 47-2, allows the use of findings from endoscopy, imaging, and physical examination in determining the stage of disease. Regional lymph node drainage is considered to be the superficial and deep inguinal lymph nodes, as well as pelvic nodes.12

Table 47-2 Classification of Penile Cancers

Rights were not granted to include this table in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book.

Management

Various techniques using both brachytherapy and external-beam radiotherapy have been described in the literature.28

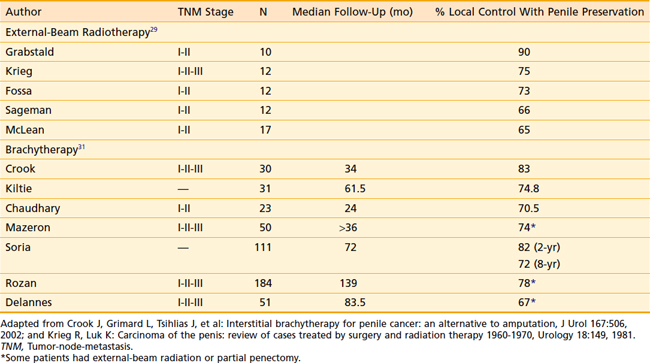

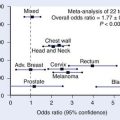

For external-beam techniques using megavoltage radiation beams, tissue equivalent bolus is required (usually wax, plastic, or a water bath is used) to provide sufficient dose buildup to the surface of the lesion. The penis is suspended and surrounded by bolus above the abdomen and radiation beams treat the whole length of the penis. When the pelvic lymph nodes are being treated, the penis can be secured cranially into the pelvic field and irradiated. Typical doses are 65 to 70 Gy to the gross tumor volume (GTV) in standard fractionation. This is usually accomplished by treating the entire length of the penis initially to a dose of 45 to 50 Gy, and performing a 10 to 20 Gy cone-down boost to the GTV. Acute reactions such as swelling, discomfort, and desquamation are usually self-limiting. Care should be taken to avoid secondary infections that may result from skin breakdown. The use of large fraction sizes should be avoided to reduce the risk of late radiation effects such as fibrosis. The incidence of stricture or stenosis has been reported to be 16% to 49%. The majority of patients (up to 90%) maintain sexual potency.29,30 The published local control rates for stage I and II cancers of the penis range from 65% to 90%, with a mean of 75%.25 Table 47-3 provides a summary of outcomes of external-beam radiotherapy.

Brachytherapy is indicated in lesions less than 4 cm in diameter and less than 1 cm of invasion into the corpora cavernosa. There are generally two techniques employed: molds (plesiobrachytherapy) and interstitial implants. When using molds, radioactive sources (generally iridium-192 [192Ir]) are placed into contact with the lesion and tissue to be irradiated. The mold holds the sources and the patient wears the mold for a calculated amount of time daily (usually 12 hours a day for 1 week). The penis is placed in a cylinder loaded with 192Ir sources. The target dose to the target is 60 Gy, while the urethra should receive less than 50 Gy. Typically, this technique is reserved for superficial tumors only and requires a competent brachytherapist and a high degree of patient cooperation.31

Interstitial implants are generally performed under a spinal or general anesthetic. A Foley catheter is introduced and kept in place for the duration of the implant. Metal or plastic catheters are placed perpendicular to the long axis of the penis and spaced parallel to each other, 1 to 1.5 cm apart, held in place with acrylic templates located at the entry and exit points of the catheters. Radioactive sources, typically 192Ir, are afterloaded into each catheter to deliver the prescribed dose of radiation. Prescribed doses range from 55 to 60 Gy, with a mean dose of 60 Gy given at a dose rate of 68 cGy/hr.32 It has been recommended that no more than 65 Gy be prescribed for T1 or T2 tumors because of the risk of significant necrosis.31 Local control rates between 78% and 95% have been reported. Significant increases in urethral strictures have been noted when treating T3 tumors that invade the urethra. In such cases, surgery is advisable over brachytherapy. The rate of penile preservation ranges between 74% and 95% for T1 and T2 lesions. Approximately 10% to 40% of patients experience urethral stenosis that requires dilation (usually at the meatus) after interstitial brachytherapy. Potency is preserved in 80% to 90% of patients.25,31–33 It has been observed that diabetic patients are more likely to experience radiation therapy–related toxicity.31

Crook et al.34 have found tumor grade to be a signficant predictor of regional and distant replase. In their series, 48.5% of moderately to poorly differentiated tumors relapsed, whereas only 3% of well-differentiated tumors had relapsed (P = 0.005).34 Prophylactic groin node irradiation is generally not recommended. Lymph nodes may be enlarged secondarily to infection and may reduce in size with a course of antibiotics. Cooperative patients with well-differentiated tumors confined to the glans are well suited for observation. The management of clinically N0 groins in patients with poorly differentiated tumors or deeply invasive lesions is controversial.

Although no randomized trials regarding the efficacy of radiation therapy versus surgery for the management of primary penile carcinoma have been conducted, radiation therapy appears to be a reasonable consideration for T1 and T2 tumors smaller than 4 cm in size. Table 47-3 summarizes the reported results of radiotherapy as primary therapy for penile cancers.

There is significant experience with the use of brachytherapy in the management of penile carcinomas, particularly in Europe. In France, brachytherapy has been the treatment of choice for clinically localized squamous cell carcinomas of the penis for several decades.32 Although late effects such as strictures or stenosis may occur in up to 40% of patients, these are usually easily remedied with simple dilation. Sexual function is also preserved in most men. Even in the setting of recurrence, surgery is a highly successful (>80%) salvage modality after either external-beam treatment or brachytherapy. Limited surgery, such as a partial penectomy, is often sufficient for salvage.33,35–37

1 American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2001.

2 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program Public-Use Data (1973–1999), National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch, released April 2009, based on the November 2008 submission.

3 Herr H, Fuks Z, Scher H. Cancer of the urethra and penis. In: Devita V, Hellman S, Rosenberg S, editors. Cancer. Principles and Practices of Oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1997.

4 Konnak JW. Conservative management of low grade neoplasms of the male urethra: a preliminary report. J Urol. 1980;123:175.

5 Grabstald H. Proceedings: tumors of the urethra in men and women. Cancer. 1973;32:1236.

6 Hand J. Surgery of the penis and urethra. In: Campbell M, Harrison J, editors. Urology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1970:2541.

7 Mandler JI, Pool TL. Primary carcinoma of the male urethra. J Urol. 1966;96:67.

8 Fair W, Yang C. Urethral carcinoma inmales. In: Resnick M, Kursch E, editors. Current Therapy in Surgery. Toronto: BC Decker, 1987.

9 Kaplan GW, Bulkey GJ, Grayhack JT. Carcinoma of the male urethra. J Urol. 1967;98:365.

10 Dalbagni G, Zhang ZF, Lacombe L, et al. Male urethral carcinoma: analysis of treatment outcome. Urology. 1999;53:1126.

11 Grigsby PW, Corn BW. Localized urethral tumors in women: indications for conservative versus exenterative therapies. J Urol. 1992;147:1516.

12 Greene F, Page D, Fleming I. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002.

13 Heysek RV, Parsons JT, Drylie DM, et al. Carcinoma of the male urethra. J Urol. 1985;134:753.

14 Licht MR, Klein EA, Bukowski R, et al. Combination radiation and chemotherapy for the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the male and female urethra. J Urol. 1995;153:1918.

15 Krieg R, Hoffman R. Current management of unusual genitourinary cancers. Part 2: Urethral cancer. Oncology (Williston Park). 1999;13:1511.

16 Herr HW. Extravesical tumor relapse in patients with superficial bladder tumors. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1099.

17 Baskin LS, Turzan C. Carcinoma of male urethra: management of locally advanced disease with combined chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and penile-preserving surgery. Urology. 1992;39:21.

18 Johnson DW, Kessler JF, Ferrigni RG, et al. Low dose combined chemotherapy/radiotherapy in the management of locally advanced urethral squamous cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1989;141:615.

19 Tran LN, Krieg RM, Szabo RJ. Combination chemotherapy and radiotherapy for a locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the urethra: a case report. J Urol. 1995;153:422.

20 Oberfield RA, Zinman LN, Leibenhaut M, et al. Management of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the bulbomembranous male urethra with co-ordinated chemo-radiotherapy and genital preservation. Br J Urol. 1996;78:573.

21 Cohen MS, Triaca V, Billmeyer B, et al. Coordinated chemoradiation therapy with genital preservation for the treatment of primary invasive carcinoma of the male urethra. J Urol. 2008;179:536.

22 Hanash KA, Furlow WL, Utz DC, et al. Carcinoma of the penis: a clinicopathologic study. J Urol. 1970;104:291.

23 Riveros M, Lebron RF. Geographical pathology of cancer of the penis. Cancer. 1963;16:798.

24 Kochen M, McCurdy S. Circumcision and the risk of cancer of the penis. A life-table analysis. Am J Dis Child. 1980;134:484.

25 Krieg R, Hoffman R. Current management of unusual genitourinary cancers. Part 1: penile cancer. Oncology (Williston Park). 1999;13:1347.

26 Grossman HB. Premalignant and early carcinomas of the penis and scrotum. Urol Clin North Am. 1992;19:221.

27 Burgers JK, Badalament RA, Drago JR. Penile cancer. Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and staging. Urol Clin North Am. 1992;19:247.

28 McLean M, Akl AM, Warde P, et al. The results of primary radiation therapy in the management of squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;25:623.

29 Grabstald H, Kelley CD. Radiation therapy of penile cancer: six to ten-year follow-up. Urology. 1980;15:575.

30 Krieg RM, Luk KH. Carcinoma of penis. Review of cases treated by surgery and radiation therapy 1960–1977. Urology. 1981;18:149.

31 Gerbaulet A, Lambin P. Radiation therapy of cancer of the penis. Indications, advantages, and pitfalls. Urol Clin North Am. 1992;19:325.

32 Crook J, Grimard L, Tsihlias J, et al. Interstitial brachytherapy for penile cancer: an alternative to amputation. J Urol. 2002;167:506.

33 Delannes M, Malavaud B, Douchez J, et al. Iridium-192 interstitial therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;24:479.

34 Crook J, Ma C, Grimard L. Radiation therapy in the management of the primary penile tumor: an update. World J Urol. 2009;27:189.

35 Zouhair A, Coucke PA, Jeanneret W, et al. Radiation therapy alone or combined surgery and radiation therapy in squamous-cell carcinoma of the penis? Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:198.

36 Rozan R, Albuisson E, Giraud B, et al. Interstitial brachytherapy for penile carcinoma: a multicentric survey (259 patients). Radiother Oncol. 1995;36:83.

37 Kiltie AE, Elwell C, Close HJ, et al. Iridium-192 implantation for node-negative carcinoma of the penis: the Cookridge Hospital experience. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2000;12:25.