Cancer of the Lung

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

• List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with cancer of the lung.

• Describe the causes of cancer of the lung.

• List the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with cancer of the lung.

• Describe the general management of cancer of the lung.

• Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAPs presented in the case study.

• Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve.

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

The major pathologic or structural changes associated with bronchogenic carcinoma are as follows:

• Inflammation, swelling, and destruction of the bronchial airways and alveoli

• Tracheobronchial mucous accumulation and plugging

• Airway obstruction (either from blood, from mucous accumulation, or from a tumor projecting into a bronchus)

• Pleural effusion (when a tumor invades the parietal pleura and mediastinum)

Etiology and Epidemiology

Environmental or occupational risk factors for lung cancer include the following:

• Benzopyrene and radon particles associated with uranium mining

• Radiation and nuclear fallout

Types of Cancers

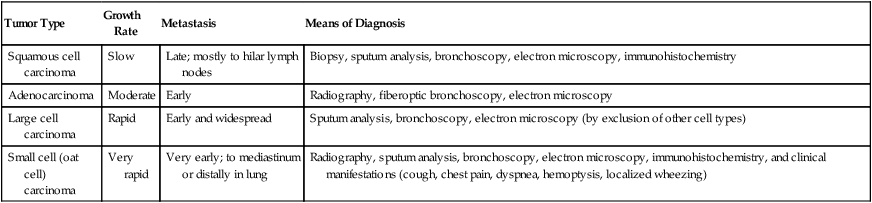

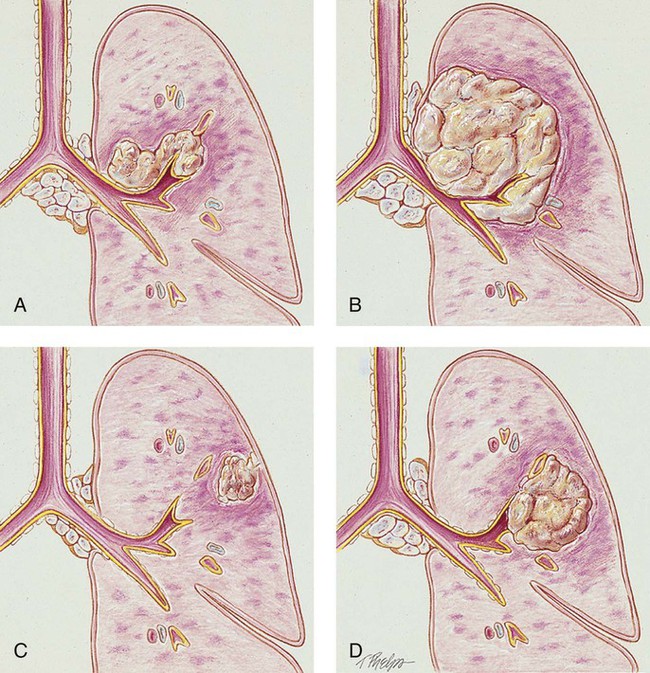

There are four major types of bronchogenic tumors: (1) squamous (epidermoid) cell carcinoma, (2) adenocarcinoma (including bronchial alveolar cell carcinoma), (3) large cell carcinoma, and (4) small cell (oat cell) carcinoma (see Figure 26-1). For therapeutic reasons, these bronchogenic tumors are commonly divided into the following two groups:

Each group grows and spreads in different way. For example, SCLC spreads aggressively and responds best to chemotherapy and radiation therapy. It occurs almost exclusively in smokers and accounts for over 20% of all lung cancers in the United States. NSCLC is more common and accounts for about 80% of all lung cancers in America. When confined to a small area and identified early, this type of cancer often can be removed surgically. Table 26-1 provides general characteristics of these cancer cell types, including growth rates, metastasis, and means of diagnosis. A more in-depth description of each cancer cell type follows.

Table 26-1

Characteristics of Lung Cancers

| Tumor Type | Growth Rate | Metastasis | Means of Diagnosis |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Slow | Late; mostly to hilar lymph nodes | Biopsy, sputum analysis, bronchoscopy, electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry |

| Adenocarcinoma | Moderate | Early | Radiography, fiberoptic bronchoscopy, electron microscopy |

| Large cell carcinoma | Rapid | Early and widespread | Sputum analysis, bronchoscopy, electron microscopy (by exclusion of other cell types) |

| Small cell (oat cell) carcinoma | Very rapid | Very early; to mediastinum or distally in lung | Radiography, sputum analysis, bronchoscopy, electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and clinical manifestations (cough, chest pain, dyspnea, hemoptysis, localized wheezing) |

Modified from McCance KL, Huether SE: Pathophysiology: the biologic basis for disease in adults and children, ed 5, St Louis, 2006, Mosby.

Non–Small Cell Lung Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma

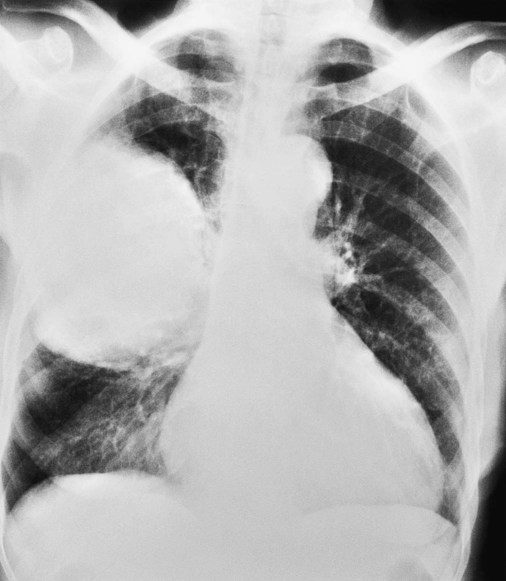

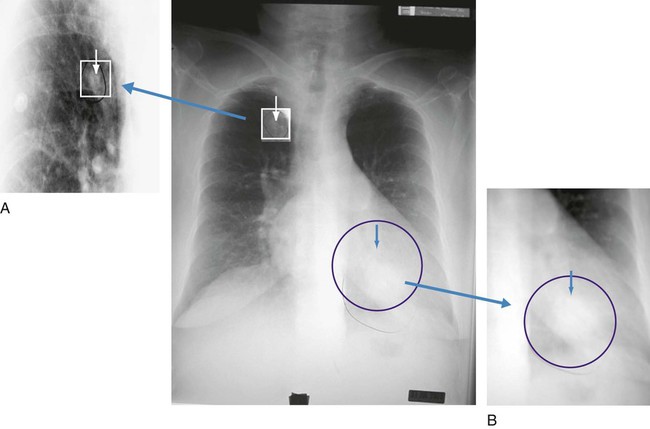

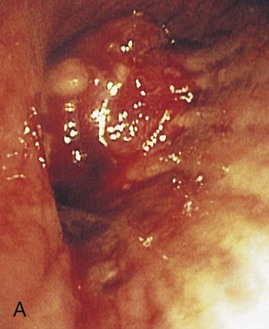

The tumor has a slow growth rate and a late metastatic tendency (mostly to hilar lymph nodes). These tumors generally remain fairly well localized and tend not to metastasize until late in the course of the lung cancer. Cavitation and necrosis within the center of the cancer is a common finding. Surgical resection is the preferred treatment if metastasis has not taken place. In about one third of the cases, squamous cell carcinoma originates in the periphery. Because of the location in the central bronchi, obstructive manifestations are generally nonspecific and include a nonproductive cough and hemoptysis. Pneumonia and atelectasis are often secondary complications of squamous cell carcinoma. Cavity formation with or without an air-fluid interface is seen in 10% to 20% of the cases (see Figure 26-1, A).

Adenocarcinoma

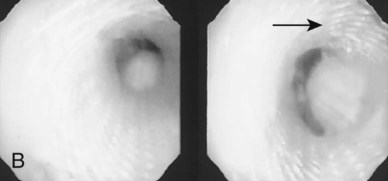

Adenocarcinoma arises from the mucous glands of the tracheobronchial tree. In fact, the glandular configuration and the mucous production caused by this type of cancer are the pathologic features that distinguish adenocarcinoma from the other types of bronchogenic carcinoma. It accounts for 35% to 40% of all bronchogenic carcinomas. Adenocarcinoma has the weakest association with smoking. However, among people who have never smoked, adenocarcinoma is the most common form of lung cancer. Adenocarcinoma tumors are usually smaller than 4 cm and are most commonly found in the peripheral regions of the lung parenchyma. The growth rate is moderate and the metastatic tendency is early. Secondary cavity formation and pleural effusion are common (see Figure 26-1, B). When the cancer is discovered early, surgical resection is possible in a high percentage of cases.

Large cell carcinoma (undifferentiated)

Large cell carcinoma accounts for about 10% to 15% of all bronchogenic carcinoma cases. Because this tumor has lost all evidence of differentiation, it is commonly referred to as undifferentiated large cell anaplastic cancer. Although these tumors commonly arise peripherally, they may also be found centrally—often distorting the trachea and large airways. Large cell carcinoma has a rapid growth rate and early and widespread metastasis. Common secondary complications include chest wall pain, pleural effusion, pneumonia, hemoptysis, and cavity formation (see Figure 26-1, C).

Small Cell Lung Carcinoma

Small cell carcinoma accounts for about 14% of all bronchogenic carcinomas. Most of these tumors arise centrally near the hilar region. They tend to arise in the larger airways (primary and secondary bronchi). Cell size ranges from 6 to 8 µm. The tumor grows very rapidly, becoming quite large, and metastasizes early. Because the tumor cells often are compressed into an oval shape, this form of cancer is commonly referred to as oat cell carcinoma. Staging for small cell carcinoma is divided into only two categories: limited disease (20% to 30%) or extensive disease (70% to 80%). Small cell carcinoma has the poorest prognosis. The average survival time for untreated small cell carcinoma is about 1 to 3 months. Small cell carcinoma has the strongest correlation with cigarette smoking and is associated with the worst prognosis (see Figure 26-1, A).

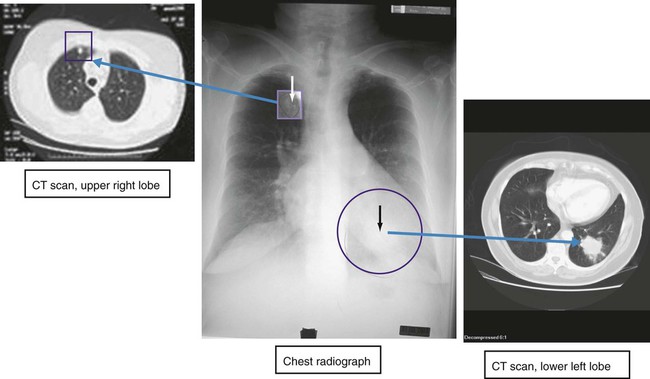

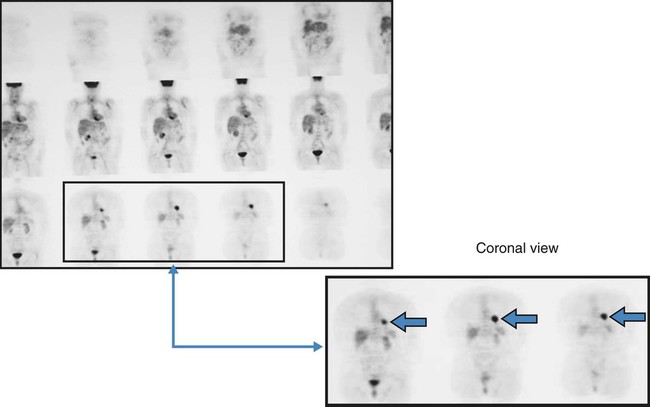

Screening and Diagnosis

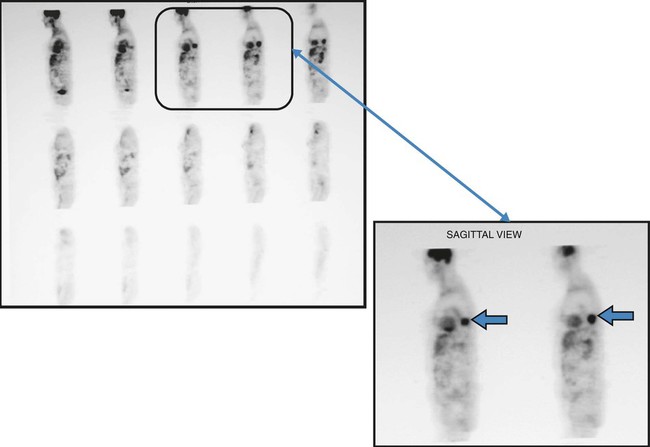

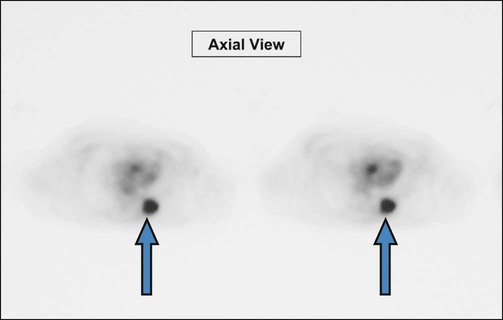

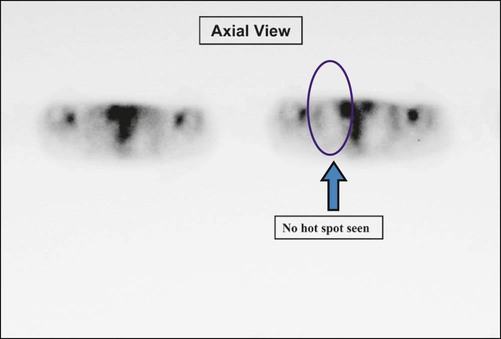

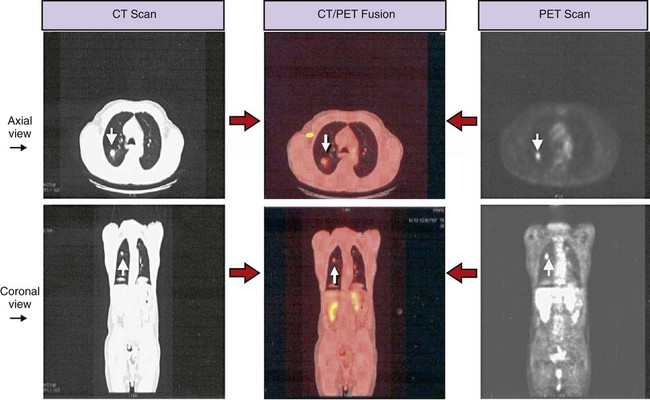

A routine chest x-ray is the most common screening test used to identify an abnormal mass or nodule in a patient’s lung. Computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans are also frequently used to reveal extremely small lesions and determine whether the cancer has spread to other areas. A definitive diagnosis, however, can be made only by viewing a tissue sample (biopsy) under a microscope. Common procedures used to obtain a tissue biopsy include bronchoscopy, thoracoscopy, mediastinoscopy, transbronchial needle biopsy or open-lung biopsy, sputum cytology, thoracentesis, and videothoracoscopy (see Chapter 8).

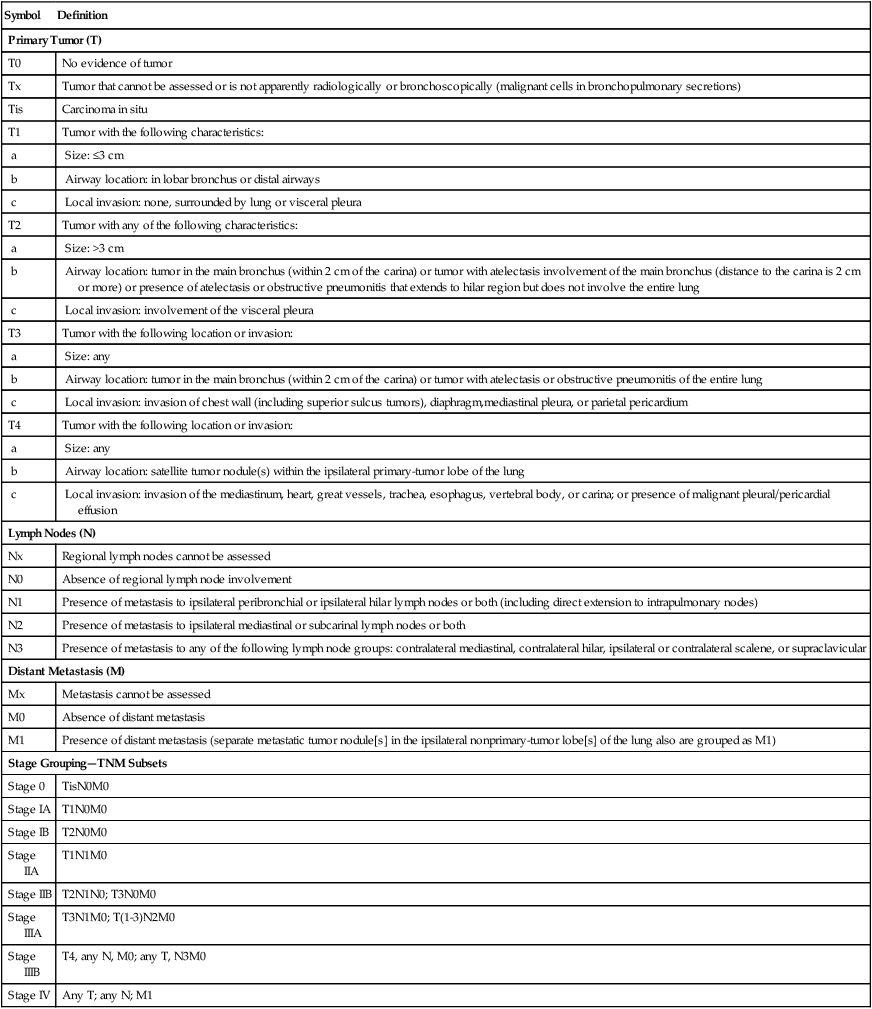

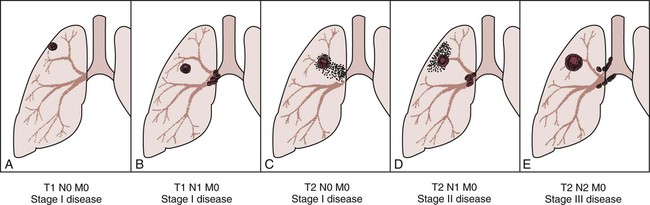

Staging of Lung Cancer

Staging is the process of classifying information about cancer. The staging system describes the cancer cell type, the size of the tumor, the level of lymph node involvement, and the extent to which the cancer has spread. The patient’s prognosis and treatment depend, to a large extent, on the staging results. The system most often used for the staging of lung cancer is the TNM classification (Table 26-2). T represents the extent of the primary tumor, N denotes the lymph node involvement, and M indicates the extent of metastasis. On the basis of the TNM findings, roman numerals are used to identify stages I through IV, with 0 being the least advanced and IV the most advanced. Figure 26-2 provides five representative illustrations of the staging of lung cancer by the TNM classification system. A general overview and description of the staging process for non–small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer follows*:

Table 26-2

1997 Revised International System for Staging Lung Cancer

| Symbol | Definition |

| Primary Tumor (T) | |

| T0 | No evidence of tumor |

| Tx | Tumor that cannot be assessed or is not apparently radiologically or bronchoscopically (malignant cells in bronchopulmonary secretions) |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

| T1 | Tumor with the following characteristics: |

| a | Size: ≤3 cm |

| b | Airway location: in lobar bronchus or distal airways |

| c | Local invasion: none, surrounded by lung or visceral pleura |

| T2 | Tumor with any of the following characteristics: |

| a | Size: >3 cm |

| b | Airway location: tumor in the main bronchus (within 2 cm of the carina) or tumor with atelectasis involvement of the main bronchus (distance to the carina is 2 cm or more) or presence of atelectasis or obstructive pneumonitis that extends to hilar region but does not involve the entire lung |

| c | Local invasion: involvement of the visceral pleura |

| T3 | Tumor with the following location or invasion: |

| a | Size: any |

| b | Airway location: tumor in the main bronchus (within 2 cm of the carina) or tumor with atelectasis or obstructive pneumonitis of the entire lung |

| c | Local invasion: invasion of chest wall (including superior sulcus tumors), diaphragm,mediastinal pleura, or parietal pericardium |

| T4 | Tumor with the following location or invasion: |

| a | Size: any |

| b | Airway location: satellite tumor nodule(s) within the ipsilateral primary-tumor lobe of the lung |

| c | Local invasion: invasion of the mediastinum, heart, great vessels, trachea, esophagus, vertebral body, or carina; or presence of malignant pleural/pericardial effusion |

| Lymph Nodes (N) | |

| Nx | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | Absence of regional lymph node involvement |

| N1 | Presence of metastasis to ipsilateral peribronchial or ipsilateral hilar lymph nodes or both (including direct extension to intrapulmonary nodes) |

| N2 | Presence of metastasis to ipsilateral mediastinal or subcarinal lymph nodes or both |

| N3 | Presence of metastasis to any of the following lymph node groups: contralateral mediastinal, contralateral hilar, ipsilateral or contralateral scalene, or supraclavicular |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | |

| Mx | Metastasis cannot be assessed |

| M0 | Absence of distant metastasis |

| M1 | Presence of distant metastasis (separate metastatic tumor nodule[s] in the ipsilateral nonprimary-tumor lobe[s] of the lung also are grouped as M1) |

| Stage Grouping—TNM Subsets | |

| Stage 0 | TisN0M0 |

| Stage IA | T1N0M0 |

| Stage IB | T2N0M0 |

| Stage IIA | T1N1M0 |

| Stage IIB | T2N1N0; T3N0M0 |

| Stage IIIA | T3N1M0; T(1-3)N2M0 |

| Stage IIIB | T4, any N, M0; any T, N3M0 |

| Stage IV | Any T; any N; M1 |

From Mountain CF: Revisions in the international system for staging lung cancer. Chest 111(6):1710, 1997.

Non–Small Cell Lung Carcinoma

• Stage 0: The cancer is limited to the lining of the bronchial airways. There is no involvement of the lung tissue or distant metastasis. Stage 0 cancers usually are found during bronchoscopy. When found and treated early, cancers at this stage can often be cured. (TisN0M0)

• Stage I: The tumor is less than 3 cm and is located in lobar or distal airways. There is no lung tissue involvement or distant metastasis. (T1N0M0)

• Stage II: In this stage the cancer has invaded neighboring lymph nodes or spread to the chest wall. There is no distant metastasis. (T1N1M0)

• Stage IIIA: The tumor is any size. The tumor is in the main bronchus, or the tumor is accompanied by atelectasis or obstructive pneumonitis of the entire lung. Local invasion involves chest wall, diaphragm, mediastinal, pleural, or parietal pericardium. There is the presence of metastasis to ipsilateral peribronchial or ipsilateral hilar lymph nodes or both. There is no distant metastasis. (T3N1M0)

• Stage IIIB: The cancer has spread locally to areas such as the mediastinum, heart, great vessels, trachea, esophagus, vertebral body, or carina, or malignant pleural or pericardial effusion is present—all within the chest. There may be involvement of any of the lymph node groups. There is no distant metastasis. (T4, any N, M0)

• Stage IV: The cancer is of any size, involves any of the lymph node groups, and has spread to other parts of the body, such as the liver, bones, or brain. (any T; any N; M1)

General Management of Cancer of the Lung

Respiratory Care Treatment Protocols

Oxygen Therapy Protocol

Oxygen therapy is used to treat hypoxemia, decrease the work of breathing, and decrease myocardial work. Because hypoxemia is associated with lung cancer, supplemental oxygen may be required. However, capillary shunting is common because of the alveolar compression and consolidation often produced by lung cancer. Hypoxemia caused by capillary shunting often is refractory to oxygen therapy (see Oxygen Therapy Protocol, Protocol 9-1).

Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol

Because of the excessive mucous production and accumulation associated with lung cancer, a number of bronchial hygiene treatment modalities may be used to enhance the mobilization of bronchial secretions (see Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol, Protocol 9-2).

CASE STUDY

Cancer of the Lung

Admitting History

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S “I’ve coughed up a cup of sputum since breakfast.”

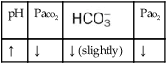

O Vital signs: BP 155/85, HR 90, RR 22, T normal; perspiring and weak and cyanotic appearance; voice hoarse-sounding; weak cough; large amounts of blood-streaked sputum; dull percussion notes over left lower lobe; rhonchi, wheezing, and crackles throughout both lung fields; recent PFTs: restrictive and obstructive pulmonary disorder; CT scan and CXR: 2- to 5-cm masses in right and left mediastinum in hilar regions and atelectasis of left lower lobe. Bronchoscopy: protruding tumors in both left and right large airways, mucous plugging. Biopsy: squamous cell bronchogenic carcinoma. ABGs (2 L/min O2 by nasal cannula): pH 7.51, Paco2 29,  24, Pao2 66; Spo2 94%.

24, Pao2 66; Spo2 94%.

• Bronchogenic carcinoma (CT scan and biopsy)

• Respiratory distress (vital signs, ABGs)

• Excessive bloody bronchial secretions (sputum, rhonchi)

• Mucous plugging (bronchoscopy)

• Poor ability to mobilize secretions (weak cough)

• Atelectasis of left lower lobe (CXR)

• Acute alveolar hyperventilation with mild hypoxemia (ABGs)

P Initiate Oxygen Therapy Protocol (4 L nasal cannula and titration by oximetry). Also begin Aerosolized Medication Protocol (0.5 mL albuterol in 2 mL 10% acetylcysteine q6h), followed by Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol (C&DB). Begin Lung Expansion Therapy Protocol (incentive spirometry q2h and prn). Closely monitor and reevaluate.

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S “I’m still not breathing very well.”

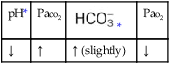

O Vital signs: BP 166/90, HR 95, RR 28, T normal; vomiting over past 10 hours; cyanosis, tiredness, and dampness from perspiration; cough: weak and productive of moderately thick, clear, and white sputum; dull percussion notes over both right and left lower lobes; rhonchi, wheezing, and crackles over both lung fields; ABGs: pH 7.55, Paco2 25,  23, Pao2 53, Spo2 92%

23, Pao2 53, Spo2 92%

• Bronchogenic carcinoma (previous CT scan and biopsy)

• Trouble tolerating chemotherapy well (excessive vomiting)

• Continued respiratory distress

• Excessive bronchial secretions (sputum, rhonchi)

• Mucous plugging still likely (previous bronchoscopy, secretions becoming thicker)

• Poor ability to mobilize secretions (weak cough)

• Atelectasis of left lower lobes; atelectasis likely in right lower lobe now (CXR, dull percussion notes)

• Acute alveolar hyperventilation with moderate hypoxemia, worsening (ABGs)

P Up-regulate Oxygen Therapy Protocol (oxygen mask). Up-regulate Aerosolized Medication Protocol (increasing treatment frequency to q3h). Up-regulate Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol (CPT and PD q3h). Up-regulate Lung Expansion Therapy Protocol (changing incentive spirometry to CPAP mask). Contact physician about possible ventilatory failure. Discuss therapeutic bronchoscopy. Closely monitor and reevaluate.

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

O Unresponsive; pale, cyanotic, and perspiring appearance; no cough noted; rhonchi heard without stethoscope; vital signs: BP 170/105, HR 110, RR 12 and shallow, T normal; rhonchi, wheezing, and crackles over both lung fields; ABGs: pH 7.28, Paco2 63,  28, Pao2 66; Spo2 89%

28, Pao2 66; Spo2 89%

• Bronchogenic carcinoma (previous CT scan and biopsy)

• Excessive bronchial secretions (rhonchi)

• Mucous plugging still likely (previous bronchoscopy, rhonchi)

P Contact physician about acute ventilatory failure, and discuss code status. Up-regulate Oxygen Therapy Protocol, Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol, and Aerosolized Medication Therapy Protocol. Monitor and reevaluate.

Discussion

This case demonstrates the few specific treatments that a respiratory care practitioner can bring to the care of patients with lung cancer. Specifically, it illustrates that most of the patients have concomitant obstructive pulmonary disease with a need for good Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy (see Protocol 9-2). The patient’s comfort must be kept in mind at all times.

The rhonchi, wheezing, and crackles indicated the need for vigorous bronchial hygiene therapy. The atelectasis in the left lower lobe suggested that a trial of careful Lung Expansion Therapy Protocol (Protocol 9-3) was in order (see Figure 9-8). The ABG values assessed with the patient on 2 L/min O2 showed acute alveolar hyperventilation with moderate hypoxemia. A trial of oxygen by Venturi mask (or nonrebreathing mask) would be helpful. Patient anxiety may be alleviated with appropriate treatment of the hypoxemia.

*Not all the subcategories for each stage are provided in this overview. See Table 26-2 for all the stages and their respective definitions.

values will be lower than expected for a particular Pa

values will be lower than expected for a particular Pa

)

)

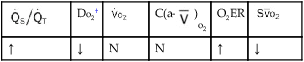

)O2, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;

)O2, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;  , pulmonary shunt fraction;

, pulmonary shunt fraction;  , mixed venous oxygen saturation;

, mixed venous oxygen saturation;  , oxygen consumption.

, oxygen consumption.

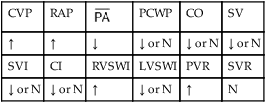

, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricular stroke work index; SV, stroke volume; SVI, stroke volume index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricular stroke work index; SV, stroke volume; SVI, stroke volume index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

24, and Pa

24, and Pa 23, and Pa

23, and Pa 28, and Pa

28, and Pa