42 Cancer of the Anal Canal

Epidemiology, Etiology, Genetics, and Cytogenetic Abnormalities

Cancers of the anal region account for 1% to 2% of all large bowel cancers and 4% of all anorectal carcinomas. The majority of these patients (75% to 80%) have squamous cell carcinomas.1 Approximately 15% have adenocarcinomas.

In 2007, a total of 4650 cases of cancers of the anal region were reported in the United States, including 1900 men and 2750 women.2 It is estimated that there will be 690 deaths per year. Anal cancers, although still uncommon, have increased substantially in incidence during the last 30 years. This increase may be due to sexual transmission of human papilloma virus (HPV), especially HPV-16 and HPV-18.3 It is postulated that, as in cervical carcinoma, with which HPV is strongly associated and may be a necessary factor for development of the disease, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) are the immediate precursors to anal cancer.4,5

Whereas anal squamous intraepithelial lesions are rare in heterosexual men, the incidence is 5% to 30% in HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM). These changes are rare among HIV-negative women, yet common in women with immunosuppression and HPV-related dysplasia of the lower genital tract.6 Anal squamous intraepithelial lesions are linked to HPV and are common in MSM and immunosuppressed patients, especially those who are HIV-positive.7,8 The prevalence of HSIL in HIV-positive MSM reaches 52%.9

There is a clear association between HIV and anal canal cancer. Cross-referencing U.S. databases for AIDS with those for cancer, the relative risk of anal cancer in homosexual men at the time of or after AIDS diagnosis was 84.1.10 The relative risk of anal cancer for up to five years before AIDS diagnosis was 13.9. In a series of 3595 patients undergoing a solid organ transplant the incidence of anal cancer was 0.11%, corresponding to a relative risk of approximately 110.11

Mutations in or aberrant expression of genes in key cellular pathways have been implicated in anal cancer. Overexpression of p53 protein has been studied in patients receiving radiation and chemotherapy (combined modality therapy [CMT]). In an analysis involving approximately 20% of patients entered on both arms of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) protocol 87-04 there was a trend towards adverse outcome (decreased local control and survival) in patients overexpressing p53.12 In one study of 55 patients, MIB-1 murine monoclonal antibody measuring KI-67 failed to predict outcome for patients treated with radiation with or without chemotherapy.13 Patel et al. proposed that activation of AKT, possibly through the PI3K-AKT pathway, is a component of the development of squamous cell cancers.14 This latter finding may be of interest now that PI3K-AKT pathway inhibitors are entering early clinical trials.

Anatomy

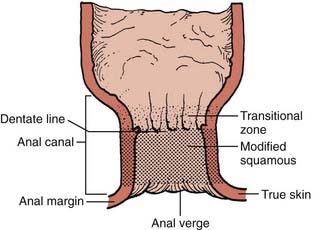

Cancers of the anus can occur in three regions; the perianal skin, the anal canal, and the lower rectum (Fig. 42-1). The anal canal is 3 to 4 cm long and extends from the anal verge to the pelvic floor.15 A clear anatomic distinction between the anal canal and the anal margin is needed, because of the different natural histories of cancers that arise in these two anatomic areas. There is considerable confusion when comparing series in the literature because of the use of different definitions of the anal canal and the anal margin.

FIGURE 42-1 • Anatomy of the anal region.

(From Nigro ND: Neoplasms of the anus and anal canal. In Zuidema GD, ed. Shackelford’s Surgery of the Alimentary Tract, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1991, WB Saunders, p 319.)

To clarify this issue, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) formed a consensus that the anal canal extends from the anorectal ring (dentate line) to the anal verge.16,17 This is an important distinction, since these two governing bodies agree that anal margin tumors behave in a similar fashion to skin cancers and therefore are to be classified as skin tumors and treated as such. However, if there is any involvement of the anal verge by tumor then it should be treated as an anal canal cancer.

An alternative and clinically oriented classification includes intra-anal, perianal, and skin.18 Intra-anal lesions cannot be visualized or are incompletely visualized when traction is applied to the buttocks. Perianal lesions are visible and are located within 5 cm of the anal opening when traction is applied to the buttocks. Skin lesions are located outside this 5 cm radius and are treated, as stated above, as skin cancers.

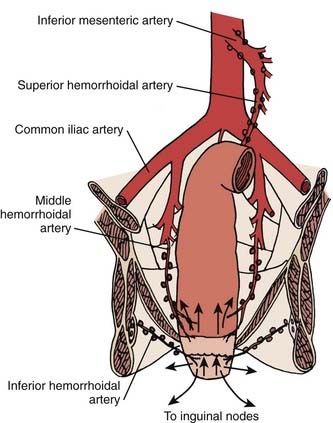

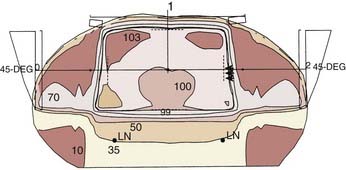

The anal region has an extensive lymphatic system, and there are many connections between the various levels (Fig. 42-2). The three main pathways include (1) superiorly from the rectum along the superior hemorrhoidal vessels to the inferior mesenteric lymph nodes, (2) from the upper anal canal and superior to the dentate line along the inferior and middle hemorrhoid vessels to the hypogastric lymph nodes, and (3) inferior from the anal margin and anal canal to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.

Pathology

There are a variety of histologic cell types which are present in the anal area (Table 42-1).19 The most common is squamous cell carcinoma. Since the mucosal epithelium over the rectal columns is cuboidal, transitional (cloacogenic) carcinomas can arise. Most investigators agree that prognosis is more dependent on stage than histologic subtype. By contrast, using a multivariate analysis, Das and associates from the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center reported a higher distant metastasis rate for patients with basaloid histologies.20 Adenocarcinomas can arise from anal crypts and should be treated as a rectal cancer though with a higher risk of inguinal node spread, given their location and lymphatic flow compared with rectal adenocarcinomas.21 In this chapter, squamous cell and cloacogenic histologies are collectively defined as anal canal cancers. Other rare histologic entities can arise, such as small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas,22 lymphoma, and melanomas.23,24

| Type of Cancer | % |

|---|---|

| Squamous cell | 63 |

| Transitional (cloacogenic) | 23 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 7 |

| Paget’s disease | 2 |

| Basal cell | 2 |

| Melanoma | 2 |

Modified from Peters PK, Mack TM: Patterns of anal carcinoma by gender and marital status in Los Angeles County, Br J Cancer 48:629, 1983.

Routes of Spread

The primary routes of spread of anal canal cancer are direct extension into soft tissues and lymphatic pathways (see Fig. 42-2). Hematogenous spread is less common. At the time of presentation, pelvic lymph node metastases occur in 30% of patients and inguinal lymph node metastases in 15% to 35%.25 The incidence of metachronous inguinal node metastasis in patients who initially present with clinically negative nodes and are not treated to the inguinal nodes is T1:10%; T2:8%; T3:16%; and T4:11%.26 Most inguinal lymph node metastases are unilateral.

Diagnostic and Staging Studies

Required as well as optional diagnostic and staging studies for anal cancer are shown in Table 42-2. Transanal ultrasound may help identify the depth of tumor penetration, but this has not been validated as a staging tool.27 Abdominal/pelvic computed tomographic (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred imaging study. In a series of 41 patients, fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) detected 91% of nonexcised primaries compared with 59% using CT alone.28 In addition, 17% of inguinal nodes negative by CT and physical examination were positive by PET. In a separate trial by Nguyen and colleagues, FDG-PET upstaged 17% of patients with CT-staged N0 disease to N+.29 However, PET, like sentinel node mapping,30 remains investigational. At present, there are no reliable serum tumor markers.

Used with the permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original source for this material is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, ed 7, 2010, published by Springer Science and Business Media, LLC, www.springerlink.com.

Staging

In 1997, the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) developed a common staging system. This staging system takes into account the fact that anal canal carcinoma is treated primarily by CMT or, in selected cases, by radiation alone. Abdominoperineal resection (APR) is reserved for patients failing initial treatment. Thus, the TNM classification for anal canal cancers is clinical. The primary tumor is assessed for size and, for T4 tumors, invasion of local structures such as the vagina, urethra, or bladder. The sixth edition of the AJCC staging system is shown in Table 42-3.31 Additional descriptors, although they do not affect the stage grouping, indicate cases needing separate analysis.

Standard Therapeutic Approaches

Treatment of High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions

Though generally accepted as the putative precursor of anal cancer, there is controversy as to the optimal management of HSIL.32 The authors use a targeted approach using high resolution anoscopy to detect dysplastic lesions and electrocautery for destruction. Even patients who are managed in this fashion, if they have a near-circumferential or circumferential anal HSIL5 experience a significantly lower malignant progression rate than those who are only observed (1.2% versus 8% to 13%).33–35 Furthermore, any remaining disease can be safely treated with office-based procedures.

Surgery

Local Excision

Local excision has been used in highly selected patients with tumors that are less than 2 cm in diameter, well-differentiated, or tumors found incidentally at the time of hemorrhoidectomy. Of 188 patients with anal canal carcinoma treated at the Mayo Clinic, a subset of 19 were treated with local excision.22 For the 12 patients with tumors confined to the epithelium and subepithelial connective tissues, 11 had tumors less than 2 cm in size and 1 patient had two lesions. Overall survival for these patients was 100%. One of 12 patients recurred, and this patient was without evidence of disease 5 years after an APR. Patients with tumors penetrating into muscle who refused a colostomy had a higher recurrence rate. These patients often can be salvaged with an APR or CMT.

Ortholan and associates treated 66 patients with T1/TIS (carcinoma in situ) tumors with brachytherapy with or without small field external beam radiation.36 With a median follow-up of 50 months, there were six local failures of which four occurred outside of the radiation field.

Radical Surgery

Radical surgery is reserved for salvage in patients who have failed radiation or in patients who have received previous pelvic radiation therapy. Procedures include APR or more extensive multivisceral resections (i.e., pelvic exenteration). In one series, salvage procedures were associated with high morbidity and mortality rates, 72% and 5%, respectively.37 However, using this radical approach, 83% of patients had negative margins and the 5-year overall survival was 39%.

Combined Modality Therapy

Until the late 1970s, the conventional treatment for anal canal cancer was an APR. Nigro et al. challenged this practice with a report of patients with squamous cell cancer of the anal cancer who following preoperative treatment with 30 Gy plus concurrent fluorouracil (5-FU) and mitomycin-C were found to have a pathologic complete response at the time of surgery.38

Since that time, increasing evidence from single-arm phase II studies has indicated that initial CMT yields a complete response rate of approximately 80% to 90% in most patients. Surgery, most commonly an APR, is reserved for salvage. Even in patients with large (≥5 cm) primary cancers, although the complete response rates are lower (50% to 75%), the majority of patients may be spared a colostomy and have an excellent overall survival. The results of these trials will be discussed in “Outcomes.”

Although CMT has been the standard of care since the 1980s, a review of 38,882 patients with anal cancer registered in the National Cancer Data Base from 1985 to 2005 revealed that only 75% received that treatment.39 In addition, those treated with CMT (plus surgery) had higher 5-year survival rates compared to those who did not receive CMT (65% versus 58%, P < .0001)

Techniques of Radiation Therapy

Introduction

A comprehensive discussion of techniques to decrease the toxicity of pelvic radiation such as physical maneuvers, immobilization molds, dietary supplements and radioprotectors, three-dimensional (3D) treatment planning, and other investigational approaches is presented in Chapter 41 (Rectal Cancer) and will not be discussed in this chapter. However, some general principles specific to the design and delivery of radiation for anal cancer will be discussed.

Design of Radiation Therapy Fields for Anal Cancer

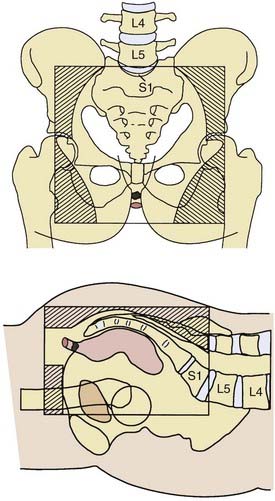

The design of pelvic radiation therapy fields for anal cancer is based on knowledge of the natural history of the disease and the primary nodal drainage. Since the internal iliac and presacral nodes are posterior in reference to the external iliac nodes, much of the normal structures in the anterior pelvis can be spared with the use of lateral fields. This approach will underdose the inguinal nodes however they can be supplemented with electrons. General guidelines for the design of pelvic radiation therapy fields for anal cancer are listed in Table 42-4.

Table 42-4 General Guidelines for Radiation Therapy in Anal Cancer

Pelvic Field

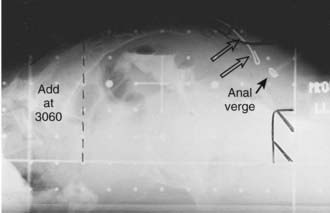

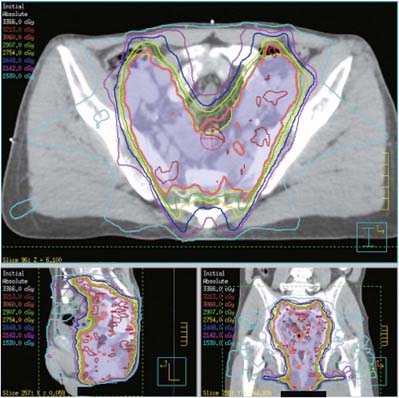

A prone three-field technique (posteroanterior [PA] plus opposed laterals) is recommended. Examples are seen in Figs. 42-3 and 42-4. This arrangement results in the lowest dose to the anterior structures such as the genitalia and bladder. The underdosed inguinal nodes are then treated concurrently with electrons to bring the dose up to 100% of the prescription dose. An alternative method is to use an AP/PA technique. Although this technique treats the pelvic and inguinal nodes in the same field it results in the highest dose to the anterior pelvic structures and skin thereby increasing toxicity. An electron boost for the perineum is not recommended since there will be overlap between the electron and photon fields. The portion of the perineum that needs to be treated should be included in the photon fields. The whole pelvis receives 30.6 Gy followed by a 14.4 Gy cone-down to the true pelvis, for a total dose of 45 Gy. Dosimetry from a representative conventional three-field plan is shown in Fig. 42-5.

It is interesting to note that in the retrospective analysis of 167 patients reported by Das et al, all 5 of the pelvic recurrences occurred at the bottom of the sacroiliac joints (SJ) joints. This is the superior border of the true pelvic field and superior border of the boost field that begins at 30.6 Gy.20

Medial and Lateral Inguinal Lymph Nodes

Following treatment of the pelvis in the prone position the patient is placed in the supine position and the inguinal nodes are treated with electrons. The medial and lateral inguinal nodes are outlined with a 2-cm margin in all directions. The inguinal nodes are included in the PA pelvic photon field. They receive only exit dose from this field; usually approximately 30% to 40% of the pelvic field prescription. This is determined from the treatment plan. Since they need to receive a total of 1.8 Gy/day, the remaining dose should be given concurrently with electrons. The depth of the inguinal nodes can be determined from a CT scan.40,41 If this is not available, a clinical estimate may be used. If the inguinal lymph nodes are biopsy-positive, a three-field technique is still recommended. However, a four-field technique (AP/PA plus opposed laterals) may be needed in order to adequately treat the external iliac nodes. In this setting, inguinal node dose should be 50.4 Gy.

Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is being actively investigated as a method to deliver pelvic radiation therapy with lower acute and long-term toxicity.42,43 Through identification of the dose limiting tissues surrounding the primary tumor and pelvic nodes and by using multiple radiation fields to avoid them, IMRT may allow for dose escalation with less toxicity. Salama and associates treated 53 patients with IMRT-based CMT.44 Patients received 45 Gy to the whole pelvis followed by a boost to a median of 51.5 Gy. Acute grade 3 toxicities were 15% gastrointestinal and 28% skin. Acute grade 4 toxicities included 30% leukopenia and 34% neutropenia. With a median follow-up of 15 months, control rates were local: 84% and distant: 93%. Survival was colostomy free: 84% and overall: 93%. IMRT is being prospectively evaluated by the RTOG (RTOG 0529). An example of an IMRT-based treatment plan is displayed in Fig. 42-6.

Brachytherapy

In contrast to treatment programs in the United States and Canada in which patients receive combined external beam plus chemotherapy, many patients treated in selected European centers receive external beam radiation therapy alone, with or without brachytherapy. The nonrandomized data suggest that the results of radiation therapy alone are comparable to combined radiation therapy plus chemotherapy.45 Brachytherapy techniques commonly involve afterloading iridium-192 (192Ir). A frequent treatment approach is external beam for the first 45 Gy followed by an additional 15 to 20 Gy with a perineal boost or brachytherapy. These are discussed in the “Outcomes” section.

Critical Normal Tissues

As seen with other cancer therapies, pelvic radiation is associated with acute and long-term toxicity. Complications of pelvic radiation therapy are a function of the volume of the radiation field, overall treatment time, fraction size, radiation energy, total dose, and technique. Large field sizes, a short overall treatment time, large fraction sizes (>2.0 Gy/day), orthovoltage or low-energy megavoltage radiation (cobalt-60), doses of >50.4 Gy when there is small bowel in the field, the use of an AP/PA technique, treatment of only one field per day, a direct perineal boost field, and the lack of computerized dosimetry all contribute to an increased incidence of radiation complications. Split course pelvic radiation is associated with an increase in chronic bowel complications and, in one series, a lower local control rate.46 Critical normal tissues that need to be considered in the treatment of anal canal cancer include bone marrow, rectum, small bowel, bladder, and skin. The acute toxicity is due to a combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Toxicities include leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, proctitis, diarrhea, cystitis, and perineal erythema. It must be emphasized that even when pelvic radiation is delivered with appropriate doses and techniques, almost all patients receiving CMT for anal cancer will develop acute grade 3+ toxicity requiring a treatment break at some point in their treatment coursecommonly the third week. Even when appropriate radiation techniques are used, approximately 1% of patients will develop severe long-term toxicity.

Unless there is a contraindication, the most simple techniques to decrease radiation toxicity such as the use of small bowel contrast, multiple field techniques, high-energy linear accelerators, custom blocks, avoiding a direct perineal boost, and treatment in the prone position should be part of the standard treatment of patients receiving curative pelvic radiation therapy. These are outlined in Table 42-5. Small bowel contrast is essential to determine the position of the small bowel during simulation. Any physical maneuver beyond the use of the prone position such as a belly board, abdominal wall compression, or a full bladder may be associated with patient discomfort, thereby leading to increased movement and daily set-up errors.

Radiation therapy can affect sphincter function. There is an increasing body of literature reporting the impact of radiation therapy on functional results in rectal cancer.47 However, it is not directly applicable to anal cancer, since patients do not undergo pelvic surgery. There are limited reports of functional outcome in the anal cancer literature. One series reports that full function was maintained in 93% of patients48 and a second series that used anorectal manometry reported complete continence in 56%.49 Another reported good-to-excellent function in 93% of patients with a minimum of 1 year follow-up.50

Outcomes

The Role of Chemotherapy

Results of two prospective randomized European trials of CMT versus radiation alone (EORTC51 and UKCCCR52) support the use of CMT. In the UKCCCR trial, although the improvement in 4-year survival with CMT did not reach statistical significance (65% versus 58%) there was a significant improvement in 3-year actuarial local control (61% versus 29%).52 In the EORTC trial, CMT resulted in a higher complete response rate (80% versus 54%), and a significantly higher 5-year actuarial local control rate (68% versus 50%) and colostomy-free survival rate (72% versus 40%) but no difference in survival 57% versus 52%).51 Although neither trial revealed a significant overall survival advantage, given the improvement in local control and colostomy-free survival, they helped to establish CMT as the standard of care.

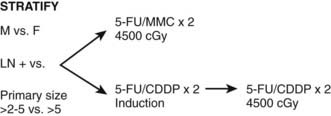

In North America, CMT has been well established, and randomized trials focus on defining the ideal regimen. The role of mitomycin-C as a necessary component was established by the intergroup trial RTOG 87-04.53 Patients were randomized to 45 Gy plus continuous infusion 5-FU with or without mitomycin-C. At 6 weeks following the completion of treatment, patients with less than a complete response had an additional 9 Gy to the primary tumor plus concurrent 5-FU/cisplatin as salvage therapy. If there was still less than a complete response 6 weeks after the completion of this salvage therapy, an APR was performed. Patients who received mitomycin-C had a higher complete response rate (92% versus 85%) and a significantly lower colostomy rate (9% versus 22%) and a corresponding significant increase in colostomy-free survival (71% versus 59%). There was little difference in overall 4-year survival (75% versus 70%). Early grade 4+ toxicity was significantly increased in the mitomycin-C arm (23% versus 7%). Although overall survival was not significantly increased given the advantage in colostomy-free survival, mitomycin-C is considered a necessary component of CMT.

The most recently completed randomized phase III trial in anal cancer (RTOG 98-11) compared a cisplatin 5-FU regimen with the standard 5-FU/mitomycin-C therapy described above.54 Unfortunately, the cisplatin-based experimental arm failed to improve disease-free survival and resulted in a significantly worse colostomy rate compared with the control arm.

Therefore, the radiation/5-FU/mitomycin-C regimen from RTOG 87-04 remains the standard of care. Substitution of an oral fluoropyrimidine, capecitabine, for continuous infusion 5-FU has been demonstrated to be safe with comparable efficacy in phase II trials.55 Though substitution of capecitabine for 5-FU has not been examined in a phase III trial, the relative rarity of anal cancers and the fact that capecitabine and 5-FU have been shown to be equally effective in multiple other settings it is reasonable to use it. Other CMT approaches including the use of oxaliplatin55 are being investigated.

Trials are currently underway testing the role of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors as a component of CMT for anal cancers. Cetuximab, an antibody to EGFR, is effective in colorectal cancer and has been shown to be effective in head and neck cancers when used concurrently with radiation.56 Cetuximab is being studied in combination with cisplatin, 5-FU, and concurrent radiation for anal cancer by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG 3205).

In two retrospective series limited to patients a small volume T1N0 lesion, those with residual microscopic disease after a local excision, or an incidental invasive cancer found after polypectomy, CMT using limited radiation doses and field sizes have been used.57,58 Both report high local control and disease-free survival. However, it must be emphasized that these are selected series and conventional doses and field sizes remain the standard.

Is Biopsy Necessary at 6 Weeks?

There is considerable controversy as to the need for the first biopsy at 6 weeks following initial treatment. Data from the Princess Margaret Hospital suggest that squamous cell cancers of the anus regress slowly and continue to decrease in size for 3 to 12 months after the completion of CMT.59 On the basis of these data, an increasing number of investigators advocate a more conservative approach and do not recommend a posttreatment biopsy. In the Intergroup trial, of the 25 patients with biopsy residual disease after 45 Gy and 5-FU/mitomycin-C who then received salvage therapy with 9 Gy plus 5-FU/cisplatin, 55% achieved a complete response 6 weeks later (a total of 12 weeks following the completion of the initial 45 Gy).53 It is unclear if the complete response was a result of the “salvage” therapy or was due to an additional 6 weeks of tumor regression following initial therapy.

Chapet and associates performed an early biopsy (at 4 weeks) before completing the final course of external beam radiation therapy or brachytherapy in 221 patients.60 They reported that the amount of tumor progression is a strong predictor for remaining colostomy free. Furthermore, when regression was ≤80% in an initial T3 to 4 lesion, completing the radiation therapy in lieu of surgery should be questioned.

At many institutions, if there is residual disease at the 6-week posttreatment evaluation, patients do not receive the 1 week of “salvage” therapy. The patients are examined every 6 weeks and, providing the tumor continues to decrease in size, no salvage therapy is performed. However, if there is progression of disease or no response at 6 weeks following initial therapy APR is necessary. In addition to careful physical examination, anal ultrasound may be helpful in following the tumor. In the RTOG 98-11 trial, biopsy at 6 weeks following the initial 45 Gy was optional (Fig. 42-7).

For certain subgroups of high-risk patients (e.g., those with T3-4 tumors), induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemotherapy and radiation to higher doses may prove to be a useful option. This is currently being tested in a single-arm Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) trial for advanced anal canal tumors.61 CMT trials can be broadly divided into those that use either 5-FU/mitomycin-C chemotherapy or, more recently, 5-FU/cisplatin chemotherapy. At some institutions, all patients with T3-4 disease receive two cycles of induction 5-FU/cisplatin.

Mitomycin-C versus Cisplatin

Most trials using cisplatin use higher radiation doses compared to the mitomycin-C–based trials. Meropol et al reported the results of the CALGB pilot trial.61 Patients with T3-4 disease received induction 5-FU/cisplatin and concurrent 5-FU/cisplatin plus radiation and the complete response rate was 80%, colostomy-free survival was 56%, and crude survival was 78%. Although the numbers are small, the phase II data suggest that the results may be better than the mitomycin-C based regimens. However, these differences may be due to other factors such as patient selection bias and higher radiation doses, and were not confirmed in the intergroup RTOG 98-11 trial.

The intergroup randomized trial RTOG 98-11 was developed to compare conventional CMT with 5-FU/mitomycin-C versus induction 5-FU/cisplatin chemotherapy followed by CMT with 5-FU/cisplatin (see Fig. 42-7).54,62 A total of 682 patients with T2-4 squamous (86%), basaloid, or cloacogenic carcinoma of the anal canal were randomized. Patients were stratified by gender, clinical node status, and tumor size and the primary endpoint was disease-free survival. Overall, 27% had tumors >5 cm, 35% had T3-4 tumors, and 26% were clinically node-positive.

In summary, compared with mitomycin-C based conventional CMT, induction 5-FU/cisplatin followed by CMT with 5-FU/cisplatin not only failed to improve disease free survival but it increased the colostomy rate. Conventional CMT with concurrent 5-FU/mitomycin-C remains the standard of care and is recommended in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.63

Intensification of the Radiation Dose

External Beam Radiation Therapy

In an attempt to improve local control and survival, two parallel pilot trials, of radiation dose intensification were designed. In both trials, patients received 36 Gy to the pelvis (30.6 whole pelvis plus 5.4 Gy to the true pelvis) and following a 2-week break, received an additional 23.4 Gy to the primary tumor with a 2- to 3-cm margin for a total dose of 59.4 Gy. The main differences between the two trials was the type of chemotherapy. The RTOG 9208 trial64 used concurrent 5-FU and mitomycin-C whereas the ECOG 4292 trial used 5-FU and cisplatin.

The RTOG 9208 trial reported similar results to the standard regimen of 45 Gy plus 5-FU/mitomycin-C used in RTOG 89-04 except for a higher 2-year colostomy rate (30% versus 7%). Likewise, the ECOG 4292 trial did not reveal a benefit compared with conventional treatment.65 Other series have reported higher complete response rates.26

Brachytherapy

Brachytherapy is an ideal method by which to deliver conformal radiation for anal cancer while sparing the surrounding normal structures such as small intestine and bladder. In most series, patients received 30 to 55 Gy of pelvic radiation with or without 5-FU/mitomycin-C or cisplatin followed by a 15 to 25 Gy boost with Ir192 afterloading catheters. Most use low-dose rates; however, some investigators have advocated high-dose rates.66,67

Combining the series, the mean results include a complete response rate of 83% (73% to 91%), local control rates of 81% (73% to 89%), and a 5-year survival rate of 70% (60% to 84%). The primary concern is anal necrosis and reports vary from 2% to as high as 76%.67 The average is 5% to 15%.

In a retrospective review from Bruna et al, 71 patients with a variety of T and N classifications were treated with a median of 45 Gy external beam to the pelvis with or without cisplatin-based chemotherapy, followed by a median of 17.8 Gy pulsed dose rate brachytherapy.68 The 2-year actuarial local control was 90%; however, 17% had grade 3+ complications.

Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy (IMRT)

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is being actively investigated as a method to deliver pelvic radiation therapy with lower acute and long term toxicity.42,43 By identification of the dose-limiting tissues surrounding the primary tumor and pelvic nodes and using multiple radiation fields to avoid them, IMRT may allow for dose escalation with less toxicity. Salama and associates treated 53 patients with IMRT-based CMT.44 Patients received 45 Gy whole pelvis followed by a boost to a median of 51.5 Gy. Acute grade 3 toxicities were 15% gastrointestinal and 28% skin. Acute grade 4 toxicities included 30% leukopenia and 34% neutropenia. With a median follow-up of 15 months, freedom from local failure was 84%, freedom from distant failure was 93%, colostomy-free survival was 84%, and overall survival was 93%. IMRT is being prospectively evaluated in the RTOG 0529 trial.

Vuong et al retrospectively compared the toxicity and local control of 5-FU, mitomycin-C and concurrent 54 to 59 Gy delivered with IMRT (26 patients) vs 3D conformal technique (40 patients).69 Patients treated with IMRT had a significantly higher incidence of grade 3+ hematologic toxicity (42% versus 18%, P = .03) and local failure/residual disease (29% versus 15% at 1 year).

Radiation Therapy Alone

External Beam Radiation Therapy

Patients who receive radiation alone have an average local control rate of 74% (range: 61% to 100%), and a 5-year survival rate of 63% (range: 50% to 94%). Although the series of 18 patients from the Mayo Clinic had the highest survival and local control rates, they also had a high rate of complications requiring surgery (17%).70 Overall, the results are comparable to patients who receive CMT with 45 Gy plus 5-FU and mitomycin-C. However, the average incidence of complications requiring surgery is 10% (range: 3% to 17%), which probably reflects the high radiation doses that must be delivered to the primary site to control this disease when radiation therapy is the sole treatment modality.

Brachytherapy With or Without External Beam Radiation Therapy

The largest series is from the Centre Leon Berard in which 221 patients were treated over a 15-year period with external beam radiation therapy (cobalt-60) to a dose of 35 Gy, followed 2 months later by an additional 15 to 20 Gy with an 192Ir implant.71 There was a 3% rate of serious complications, 65% 5-year disease-free survival, and a 79% locoregional control rate. Another study from France confirmed a high 5-year survival rate (61%) and good local control (75%) but a 6% rate of complications requiring surgery.72

Prognostic Factors

T Classification

Peiffert et al reported an increase in local failure with T classification (T1: 11%; T2: 24%; T3: 45%; and T4: 43%) and a corresponding decrease in 5-year survival (T1: 94%; T2: 79%; T3: 53%; and T4: 19%).73 A similar decrease in 5-year colostomy-free survival with T1-2 tumors versus T3-4 tumors was reported by Gerard and colleagues (T1: 83%; T2: 89% vs T3: 50%; T4: 54%).26

N Classification

In contrast to T classification, the impact of positive lymph nodes is less clear. Unlike rectal cancer, inguinal lymph nodes in anal cancer are considered nodal metastasis (N+) rather than distant metastasis (M1), and patients should be treated in a potentially curative fashion. Cummings et al. reported that patients with negative nodes who received CMT had a higher 5-year cause-specific survival compared to those with positive nodes (81% versus 57%).59 Using univariate analysis, Allal and colleagues reported a significant increase in local failure in patients with positive versus negative nodes who received 5-FU, mitomycin-C and radiation (36% versus 19%, P = .03) however, this difference was not found to be significant by multivariate analysis.74

The RTOG 87-04 randomized trial reported a higher colostomy rate (which is an indirect measurement of local failure) in N+ versus N0 patients (28% versus 13%).53 In N− and possibly N+ patients, the addition of mitomycin-C decreased the overall colostomy rates. The EORTC randomized trial of 45 Gy with or without 5-FU/mitomycin-C also reported that patients with positive nodes experienced significantly higher local failure (P = .035) and lower survival (P = .038) rates compared to those with negative nodes. However, there was no difference in prognosis between N1 versus N2-3 disease.

Using multivariate analysis, Allal and associates found that the only variable for which there was a possible impact was overall treatment time (P = .09).46 In the EORTC randomized trial, multivariate analysis identified that positive nodes, skin ulceration, and male gender were independent negative prognostic factors for local control and survival.51 Goldman and coworkers also found that women had a more favorable outcome compared with men.75 Other authors have reported that T classification, radiation dose, and percentage hemoglobin were significant.

The multivariate analysis of 167 patients by Das et al revealed that higher T and N classification correlated with increased local failure, N classification and basaloid histology was associated with distant failure, and N classification and HIV seropositive status predicted lower survival.20 Other authors have reported that T classification, radiation dose, and percentage hemoglobin were significant. In the intergroup RTOG 98-11 trial, multivariate analysis revealed that male gender (P = .04), clinically N+ (P < .0001), and tumor size >5 cm (P = .005) were independent prognostic factors for disease-free survival.62

Histologic cell type for squamous cancers of the anal canal (squamous versus cloacogenic) has not been found to be of major prognostic relevance. Studies examining DNA content (i.e., whether tumors were diploid or nondiploid)76 and p53 expression77,78 report conflicting results.

Treatment of the HIV-Positive Patient

In general, HIV-positive patients have received lower doses of radiation and chemotherapy because of a concern that standard therapy may not be tolerated.10 With a better understanding of the immunologic deficiencies seen in HIV-positive patients, recent reports have recommended therapy based on clinical and immunologic parameters, such as a history of previous opportunistic infections and CD4 counts.79–81 The limited experience suggests that in patients with a CD4 count >200/µL who do not have signs or symptoms of other HIV-related diseases, aggressive CMT is appropriate. However, they need to be followed carefully, and frequent modifications during therapy are likely to be necessary. For those patients with a CD4 count <200/µL or who have signs or symptoms of other HIV-related diseases, attenuated doses of radiation and/or chemotherapy are recommended. In one report there was no difference in acute or late toxicities based on CD4 counts.79 It should be emphasized that most series include fewer than 20 patients and, given the heterogeneity of the patients and treatments, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions.

A recent retrospective analysis of a large national database compared the outcomes of patients with anal squamous cell carcinoma who were seropositive with those who were seronegative.82 Of a total of 1184 patients, 175 (15%) were HIV-positive. HIV-positive patients were younger (median age: 49 years versus 63 years, P < .001), more likely to be male (P = .01), and three times more likely to be African American (P < .001). Although the authors reported no difference in patients’ receipt of cancer-directed therapies between the two groups, they did not report what type of treatment was administered. However, in the fully adjusted hazard ratio model, HIV was not associated with an increased risk of death. Factors that were associated with an increased risk of death were increasing age, presence of metastasis, and having a high comorbidity score.

Treatment of Anal Margin Cancer

A more comprehensive discussion of the treatment of anal margin cancers will be covered in Chapter 67. In brief, a reasonable approach is to recommend a local excision for smaller tumors (≤4 cm) which are not in direct contact with the anal verge. If the patient requires an APR because of anatomic constraints or if a local excision would compromise sphincter function, or if the tumor is >4 cm and/or node-positive, then nonoperative treatment with CMT is an appropriate alternative. On the basis of the randomized trial from the UKCCCR (which had 23% of patients with anal margin cancers), CMT rather than radiation therapy alone is recommended. In a report from Erlangen, 5-year colostomy-free (69%) and overall survival (54%) rates for anal margin tumors treated with CMT were lower than for anal canal tumors. However, this may have been due to higher T classifications.83

Follow-Up After Treatment

In one series examining patients who failed CMT, 95% had failed within 3 years.84 The usefulness of CT of the abdomen and pelvis or FDG-PET for follow-up is unclear. Christensen and colleagues reported that sensitivity for detecting recurrences was 1.0 for 3D ultrasound combined with physical examination versus 0.86 for 3D ultrasound alone versus 0.57 for 2D ultrasound.85 Since the most common site of failure is at the primary tumor site, there is no substitute for physical examination. In a small series of 33 patients, Petrelli and colleagues report a 76% sensitivity, 86% specificity, and a 62% positive predictive of squamous cell carcinoma detected by tumor-associated antigen.86

Treatment of Metastatic Disease

Given the low incidence of anal cancer and the high success of CMT, the number of patients who develop metastatic disease is small. Single agent trials of doxorubicin (adriamycin) and of cisplatin resulting in limited responses have been reported by several investigators.87,88 Combination chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-FU has a response rate of approximately 50% using both systemic and regional (hepatic-arterial) routes.89–91 There is limited experience with newer agents such as irinotecan and cetuximab.92

1 Myerson RJ, Karnell LH, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on carcinoma of the anus. Cancer. 1997;80:805-815.

2 Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43-66.

3 Frisch M, Fenger C, van den Brule AJ, et al. Variants of squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal and perianal skin and their relation to human papillomaviruses. Cancer Res. 1999;59:753-757.

4 Freidman HB, Saah AJ, Sherman ME, et al. Human papillomaviruses, anal squamous intraepithelial lesions, and human immunodeficiency virus in a cohort of gay men. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:45-52.

5 Pineda CE, Berry JM, Jay N, et al. High resolution anoscopy targeted surgical destruction of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions: a ten-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:829-835.

6 Nahas CS, Lin O, Weiser MR, et al. Prevalence of perianal intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV-infected patients referred for high-resolution anoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1581-1586.

7 Shepherd NA. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia and other neoplastic precursor lesions of the anal canal and perianal region. Gastroenterol Clin NA. 2007;36:969-987.

8 Abramowitz L, Benabderrahmane D, Ravuad P, et al. Anal squamous intraepithelial lesions and condyloma in HIV-infected heterosexual men, homosexual men and women: prevalence and associated factors. AIDS. 2007;21:1457-1465.

9 Palefsky JM, Holly EA, Efirdc J, et al. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2005;19:1407-1414.

10 Melbye M, Cote T, Kessler L, et al. AIDS/Cancer Working Group. High incidence of anal cancer among AIDS patients. Lancet. 1994;343:636-639.

11 Aigner F, Boeckle E, Albright J, et al. Malignancies of the colorectum and anus in solid organ recipients. Transpl Int. 2007;20:497-504.

12 Bonin SR, Pajak TJ, Russell AH, et al. Overexpression of p53 protein and outcome of patients with chemoradiation for carcinoma of the anal canal: a report of the randomized trial RTOG 87-04. Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Cancer. 1999;85:1226-1233.

13 Allal AS, Alonso Pentzke L, Remadi S. Apparent lack of prognostic value of MIB-1 index in anal carcinomas treated by radiotherapy. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:1333-1336.

14 Patel H, Polanco-Echeverry G, Segditsas S, et al. Activation of AKT and nuclear accumulation of wild type TP53 and MDM2 in anal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2007;15:2668-2673.

15 Cummings BJ. Anal canal. In: Perez C, Brady L, editors. Principles and Practice of radiation oncology. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott; 1993:1015-1024.

16 American Joint Committee on Cancer. Anal canal. In: Fleming ID, Cooper JS, Henson DE, Hutter PVP, Kennedy BJ, Murphy GP, O’Sullivan B, Sobin LH, Yarbro JW, editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:91-96.

17 Anal canal. In: Sobin LH, Wittekind Ch, editors. TNM classification of malignant tumors. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1997:70-73.

18 Welton ML, Sharkey FE, Kahlenberg MS. The etiology and epidemiology of anal cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2004;13:263-275.

19 Peters RK, Mack TM. Patterns of anal carcinoma by gender and marital status in Los Angeles County. Br J Cancer. 1983;48:629-633.

20 Das P, Bhatia S, Eng C, et al. Predictors and patterns of recurrence after definitive chemoradiation for anal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:794-800.

21 Joon DL, Chao MWT, Ngan SYK, et al. Primary adenocarcinoma of the anus: a retrospective analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45:1199-1205.

22 Boman BM, Moertel C, O’Connell M, et al. Carcinoma of the anal canal, a clinical and pathologic study of 188 cases. Cancer. 1984;54:114-125.

23 Remigio PA, Der BK, Forsberg RT. Anorectal melanoma: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1976;19:350.

24 Balachandra B, Marcus V, Jass JR. Poorly differentiated tumors of the anal canal: a diagnostic strategy for the surgical pathologist. Histopathol. 2007;50:163-174.

25 Berard P, Papillon J. Role of pre-operative irradiation for anal preservation in cancer of the low rectum. World J Surg. 1992;16:502-509.

26 Gerard JP, Ayzac L, Hun D, et al. Treatment of anal canal carcinoma with high dose radiation therapy and concomitant fluorouracil-cisplatinum. Long term results in 95 patients. Radiother Oncol. 1998;46:249-256.

27 Tarantino D, Bernstein MA. Endoanal ultrasound in the staging and management of squamous-cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Potential implications of a new ultrasound staging system. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:16-22.

28 Cotter SE, Grigsby PW, Siegel B, et al. FDG-PET/CT in the evaluation of anal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:720-725.

29 Nguyen BT, Joon DL, Khoo V, et al. Assessing the impact of FDG-PET in the management of anal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2008;87:376-382.

30 Damin DC, Rosito MA, Schwartsmann G. Sentinel lymph node in carcinoma of the anal canal: a review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:247-252.

31 Anal canal. In: Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, Fritz AG, Balch CM, Haller DG, Morrow M, editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. New York: Springer; 2002:125-130.

32 Fleshner PR, Chalasani S, Chang CJ, et al. Practice parameters for anal squamous neoplasms. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:2-9.

33 Devaraj B, Cosman BC. Expectant management of anal squamous dysplasia in patients with HIV. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:36-40.

34 Scholefield JH, Castle MT, Watson NF. Malignant transformation of high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1133-1136.

35 Watson AJ, Smith BB, Whitehead MR, et al. Malignant progression of anal intra-epithelial neoplasia. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:715-717.

36 Ortholan C, Ramaioli A, Peiffert D, et al. Anal canal carcinoma: early stage tumors <10 mm (T1 or TIS) therapeutic options and original pattern of local failure after radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:479-485.

37 Schiller DE, Cummings BJ, Rai S, et al. Outcomes for salvage surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2780-2789.

38 Nigro ND, Vaitkevicius VK, Considine B. Combined therapy for cancer of the anal canal: a preliminary report. Dis Colon Rectum. 1974;17:354-358.

39 Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Ko CY, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal: utilization and outcomes of recommended treatment in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1948-1958.

40 Koh WJ, Chiu M, Stelzer KJ, et al. Femoral vessel depth and the implications for groin node radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;27:969-974.

41 Wang CJ, Chin YY, Leung SW, et al. Topographic distribution of inguinal lymph nodes metastasis: significance in determination of treatment margin for elective inguinal lymph nodes irradiation of low pelvic tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;35:133-136.

42 Meyer J, Czito B, Yin FF, et al. Advanced radiation therapy technologies in the treatment of rectal and anal cancer: intensity-modulated photon therapy and proton therapy. Clin Colorec Cancer. 2007;6:348-356.

43 Milano MT, Jani AB, Farrey KJ, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) in the treatment of anal cancer: toxicity and clinical outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:354-361.

44 Salama JK, Mell LK, Schomas DA, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and intensity-modulated radiation therapy for anal cancer patients: a multicenter experience. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4581-4586.

45 Touboul E, Schlienger M, Buffat L, et al. Epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal. Results of curative-intent radiation therapy in a series of 270 patients. Cancer. 1994;73:1569-1579.

46 Weber DC, Kurtz JM, Allal AS. The impact of gap duration on local control in anal canal carcinoma treated by split-course radiotherapy and concomitant chemotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:675-680.

47 Kollmorgen CF, Meagher AP, Pemberton JH, et al. The long term effect of adjuvant postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer on bowel function. Ann Surg. 1994;220:667-673.

48 Kapp KS, Geyer E, Gebhart FH, et al. Evaluation of sphincter function after external beam irradiation and Ir-192 high-dose-rate (HDR) brachytherapy +/− chemotherapy in patients with carcinoma of the anal canal. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45s:339.

49 Vordermark D, Sailer M, Flentje M, et al. Continence and anorectal manometry after curative-intent radiation therapy for anal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45s:340.

50 Weber DC, Nouet P, Kurtz JM, et al. Assessment of target dose delivery in anal cancer using in vivo thermoluminescent dosimetry. Radiother Oncol. 2001;59:39-43.

51 Bartelink H, Roelofsen F, Eschwege F, et al. Concomitant radiotherapy and chemotherapy is superior to radiotherapy alone in the treatment of locally advanced anal cancer: results of a phase III randomized trial of the European Orginization for Research and Treatment of Cancer radiotherapy and gastrointestinal cooperative groups. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2040-2049.

52 UKCCCR Anal Cancer Trial Working Party. Epidermoid anal cancer: results from the UKCCCR randomised trial of radiotherapy alone versus radiotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, and mitomycin. Lancet. 1997;348:1049-1054.

53 Flam M, John M, Pajak T, et al. Role of mitomycin in combination with fluorouracil and radiotherapy, and salvage chemoradiation in the definitive nonsurgical treatment of epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal: results of a phase III randomized intergroup study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2537-2539.

54 Ajani JA, Winter KA, Gunderson LL, et al. Fluorouracil, mitomycin, and radiotherapy vs fluorouracil, cisplatin, and radiotherapy for carcinoma of the anal canal. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1914-1921.

55 Eng C, Crane CH, Rosner GL, et al. A phase II study of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin and radiation therapy (XELOX-RT) in squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal: a preliminary toxicity analysis. Proc ASCO/AGA/ASTRO/SSO GI Symposium. 2005;2:192.

56 Brockstein B, Lacouture M, Agulnik M. The role of inhibitors of the epidermal growth factor in management of head and neck cancer. J Natl Comp Cancer Network. 2008;6:696-706.

57 Hatfield P, Cooper R, Sebag-Montefiore D. Involved-field, low dose chemoradiotherapy for early stage anal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:419-424.

58 Hu K, Minsky BD, Cohen AM, et al. 30 Gy may be an adequate dose in patients with anal cancer treated with excisional biopsy followed by combined-modality therapy. J Surg Onc. 1999;70:71-77.

59 Cummings BJ, Keane TJ, O’Sullivan B, et al. Epidermoid anal cancer: treatment by radiation alone or by radiation and 5-fluorouracil with and without mitomycin-C. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:1115-1125.

60 Chapet O, Gerard JP, Riche B, et al. Prognostic value of tumor regression evaluated after first course of radiotherapy for anal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:1316-1324.

61 Meropol NJ, Niedzwiecki D, Shank B, et al. Combined-modality therapy of poor risk anal canal carcinoma: a phase II study of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB). Proc ASCO. 1999;18:237.

62 Ajani JA, Winter KA, Gunderson LL, et al. Intergroup RTOG 98-11: a phase III randomized study of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), mitomycin, and radiotherapy versus 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin and radiotherapy in carcinoma of the anal canal. Proc ASCO. 2006;24:180s.

63 Engstrom PF, Benson ABIII, Chen YJ, et al. Anal canal cancer: clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Comp Cancer Network. 2005;3:510-515.

64 John M, Pajak T, Flam M, et al. Dose escalation in chemoradiation for anal cancer: preliminary results of RTOG 92-08. Cancer J Sci Am. 1996;2:205-211.

65 Martenson JA, Lipsitz SR, Wagner H, et al. Initial results of a phase II trial of high dose radiation therapy, 5-fluorouracil, and cisplatin for patients with anal cancer (E4292): an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;35:745-749.

66 Gerard JP, Mauro F, Thomas L, et al. Treatment of squamous cell anal canal carcinoma with pulsed dose rate brachytherapy. Feasibility study of a French cooperative group. Radiother Oncol. 1999;51:129-131.

67 Roed H, Engelholm SA, Svendsen LB, et al. Pulsed dose rate (PDR) brachytherapy of anal carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 1996;41:131-134.

68 RBruna A, Gastelblum P, Thomas L, et al. Treatment of squamous cell anal canal carcinoma (SCACC) with pulsed dose rate brachytherapy: a retrospective study. Radiother Oncol. 2006;79:75-79.

69 Vuong T, Faria S, Ducruet T, et al. Changes in treatment toxicity pattern using the combined treatment of patients with anal canal cancer and early local recurrence results associated with the introduction of new radiation technologies: 3D conformal and intensity modulated radiation therapy. Proc ASCO. 2008;26:240s.

70 Martenson JA, Gunderson LL. External radiation therapy without chemotherapy in the management of anal cancer. Cancer. 1993;71:1736-1740.

71 Papillon J, Montbarbon JF. Epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:324-333.

72 Ng Ying Kin KNY, Pigneux J, Auvray H, et al. Our experience of conservative treatment of anal canal carcinoma combining external irradiation and interstitial implants: 32 cases treated between 1973 and 1982. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988;14:253-259.

73 Peiffert D, Bey P, Pernot M, et al. Conservative management by irradiation of epidermoid cancers of the anal canal: prognostic factors of tumor control and complications. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:313-324.

74 Allal AS, Mermillod B, Roth AD, et al. The impact of treatment factors on local control in T2-T3 anal carcinomas treated by radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy. Cancer. 1997;79:2329-2335.

75 Goldman S, Glimelius B, Glas U, et al. Management of anal epidermoid carcinoma: an evaluation of treatment results in two population-based series. Int J Colorect Dis. 1989;4:234-239.

76 Dalby JF, Pointon RS. The treatment of anal carcinoma by interstitial irradiation. Am J Radiol. 1961;85:515.

77 Bonin SR, Qian C, Russell AH, et al. Overexpression of p53 protein is associated with decreased local disease-free survival in patients treated with chemoradiation for anal canal cancer: a report of RTOG 87-04. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;36:210-217.

78 Wong CS, Tsao MS, Sharma V, et al. Prognostic role of p53 protein expression in epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45:309-314.

79 Edelman S, Johnstone PAS. Combined modality therapy for HIV-infected patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the anus: outcomes and toxicities. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:206-211.

80 Blazy A, Hennequin C, Gornet JM, et al. Anal carcinomas in HIV-positive patients: high-dose chemoradiotherapy is feasible in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1176-1181.

81 Wexler A, Berson AM, Goldstone SE, et al. Invasive anal squamous-cell carcinoma in the HIV-positive patient: outcome in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:73-81.

82 Chiao EY, Giordano TP, Richardson P, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated squamous cell cancer of the anus: epidemiology and outcomes in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:474-479.

83 Grabenbauer GG, Kessler H, Matzel KE, et al. Tumor site predicts outcome after radiochemotherapy in squamous cell carcinoma of the anal region: long-term results of 101 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1742-1751.

84 Renehan AG, Saunders MP, Schofield PF, et al. Patterns of local disease failure and outcome after salvage surgery in patients with anal cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92:605-614.

85 Christensen AF, Nielsen MB, Svendsen LB, et al. Three-dimensional anal endosonography may improve detection of recurrent anal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1527-1532.

86 Petrelli NJ, Palmer M, Herrera L, et al. The utility of squamous cell carcinoma antigen for the follow-up of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Cancer. 1992;70:35-39.

87 Fisher W, Herbst K, Sims J, et al. Metastatic cloacogenic carcinoma of the anus: sequential responses to adriamycin and cis-dichlorodiamineplatinum (III). Cancer Treat Rep. 1978;62:91-100.

88 Salem P, Habboubi N, Naanasissie E, et al. Effectiveness of cisplatin in the treatment of anal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rep. 1985;69:891-899.

89 Ajani JA, Carrasco H, Jackson D, et al. Combination of cisplatin plus fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy effective against liver metastasis from carcinoma of the anal canal. Am J Med. 1989;87:221-229.

90 Mahjoubi M, Sadek H, Francois E, et al. Epidermoid anal canal carcinoma (EACC): activity of cisplatin (P) and continuous 5 fluorouracil (5-FU) in metastatic (M) and/or local recurrent (LR) disease. Proc ASCO. 1990;9:114.

91 Hung A, Crane CH, Delclos M, et al. Cisplatin-based combined modality therapy for anal carcinoma. A wider therapeutic index. Cancer. 2003;97:1195-1202.

92 Phan LK, Hoff PM. Evidence of clinical activity for cetuximab combined with irinotecan in a patient with refractory anal canal squamous-cell carcinoma: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:395-398.