25 Bypass Surgery for Complex MCA Aneurysms

Introduction

Complex MCA aneurysms may be categorized into three major groups based on etiology and anatomic location along the vessel: (1) M1 segment fusiform aneurysms, (2) giant MCA bifurcation aneurysms, and (3) distal MCA infectious aneurysms. Although fusiform aneurysms are relatively uncommon, the M1 segment tends to be the region of the MCA affected, perhaps due to its relationship to atherosclerotic disease.1 Among MCA aneurysms overall, the most common anatomic location is at the MCA bifurcation (or trifurcation) at the origin of the M2 branches, with saccular morphology and etiology likely related to hemodynamic forces. Distal MCA branches such as M2-M4 segments are a common site for infectious or mycotic aneurysms, often associated with favored flow routes of septic emboli from infective endocarditis.

The role of bypass surgery for complex MCA aneurysms has been somewhat tempered by the infrequency of this technically demanding procedure usually done by specialized vascular neurosurgeons at institutions with an ample referral base2 and by the rapid evolution of potential alternative endovascular therapies. Yet bypass is an essential tool in the repertoire of a vascular neurosurgeon given its sometimes crucial role in the management of complex intracranial aneurysms. In this chapter, we focus on surgical bypass treatment options for complex MCA aneurysms, including the decision-making process and details of surgical technique.

Treatment decisions

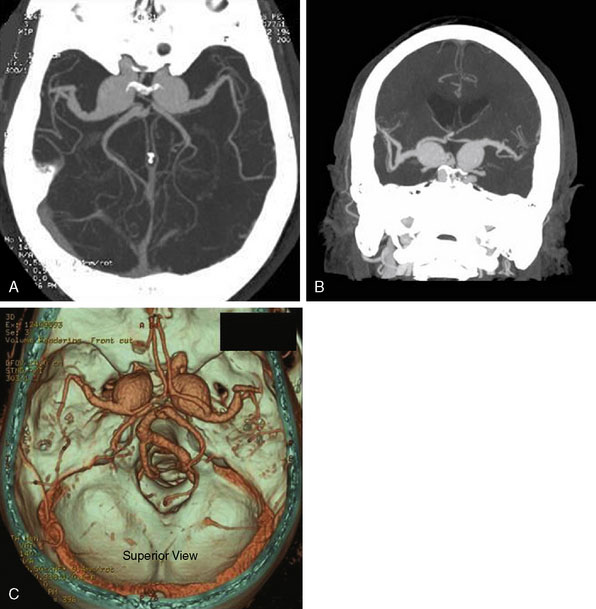

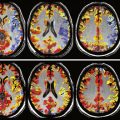

Although many of the following steps occur in parallel, generally the sequence progresses from the history/exam to imaging, then determination is made as to optimal management options that may include observation, surgical treatments, endovascular treatments, or combined surgical-endovascular treatments. For initial imaging assessment, we use CTA with maximal intensity projections and 3D image reconstruction since it is quick, noninvasive, surveys other related neuroanatomic issues (such as mass effect for giant aneurysms or any associated hydrocephalus), identifies other coexisting aneurysms, assesses the full extent of giant or complex aneurysms (such as thrombosed components) that may not be seen on conventional angiography, and outlines relationships of the target with other anatomic structures such as the skull base or proximity to potential extracranial bypass vessels.3–5 In complex scenarios, the CTA can easily be extended to the neck and aortic arch to help facilitate assessment for endovascular access or an array of surgical options. Bilateral cervical carotid and vertebral systems may also be assessed for outlining the individual’s overall intracranial hemodynamic configuration, and ECA branches such as the superficial temporal artery (STA) can be delineated in detail including 3D reconstruction. Linkage may also be done with image-guidance systems (IGS) to facilitate STA harvest or distal MCA bypass if needed. Our second choice study for those patients who cannot undergo CTA is conventional digital subtraction angiography (DSA) that can be done with contrast-minimizing strategies if needed, or least commonly MRA.

Complex MCA aneurysms that cannot be appropriately treated by surgical or endovascular trapping with possible bypass may alternatively be treated by altering blood flow to the inflow zone using various surgical and endovascular strategies.6 Endovascular options for complex MCA aneurysms may include coil or Onyx embolization (with possible stent or balloon assistance) versus flow alteration strategies or combined surgical-endovascular therapies with bypass followed by endovascular trapping or embolization.7,8 Recurrences are another category that may need special consideration and may be treated with additional surgical clipping, endovascular embolization, proximal parent vessel occlusion, or bypass with surgical or endovascular trapping.9 At our institution, complex elective cases are usually discussed in a weekly multi-disciplinary neurovascular conference involving neurosurgeons, neurologists, and interventional radiologists before final therapies are pursued. As previously mentioned, we will focus on three types of complex MCA aneurysms, which include fusiform M1 segment aneurysms, large or giant MCA bifurcation aneurysms, and distal MCA infectious aneurysms.

M1 fusiform aneurysms

Patients with M1 fusiform aneurysms may present with ischemic symptoms, stroke, mass effect, rupture with subarachnoid hemorrhage, or as an incidental finding. For a focal M1 segment fusiform aneurysm, treatment options include observation with expectant management, endovascular reconstruction, surgical trapping with EC-IC bypass, or combined endovascular-surgical therapies.10 The etiology may involve acute dissection associated with trauma versus chronic fusiform aneurysm, with the natural history of the latter being poorly understood.11 Acute dissecting aneurysms can have significant risk of associated hemorrhage.12 For chronic fusiform aneurysms, cerebral infarction related to thrombus involving compromise of perforators or thromboembolic phenomena may occur more frequently than hemorrhagic rupture based on the natural history of the more frequently encountered vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia or fusiform aneurysms.13 Treatment of choice may depend on whether the aneurysm is ruptured, unruptured but symptomatic, flow-limiting, or incidental upon presentation.

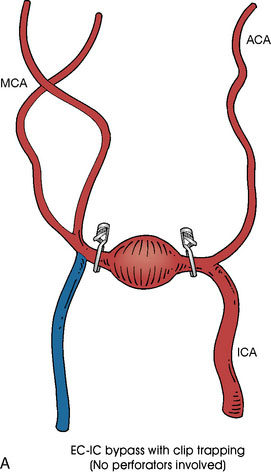

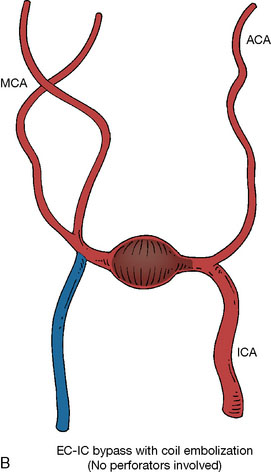

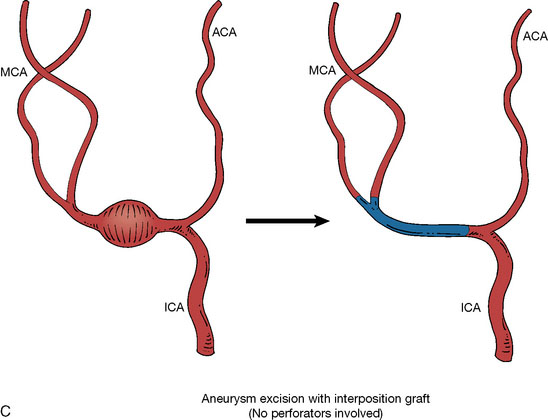

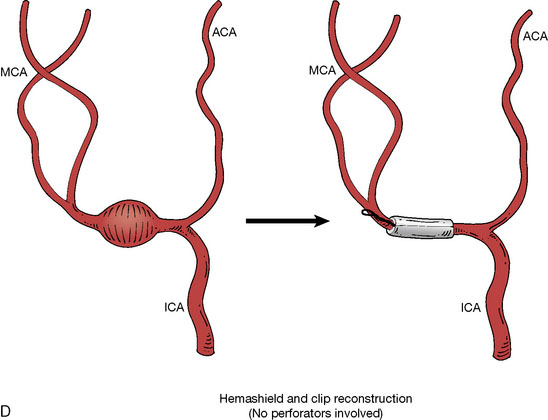

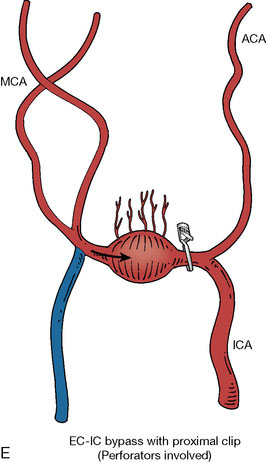

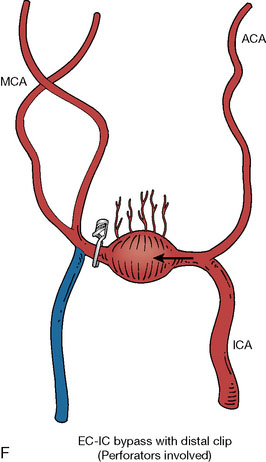

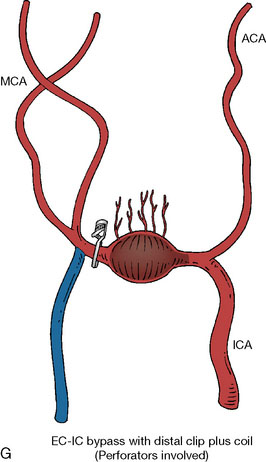

In addition, an important factor for determining appropriate treatment to minimize morbidity is the identification of significant perforators, which may emanate from the aneurysm itself and may not be fully recognized until intraoperatively. If perforators are not involved with the aneurysm, then the treatment goal is exclusion of the aneurysm from the circulation while preserving distal MCA flow using techniques such as EC-IC bypass with clip trapping or coil embolization (Figures 25–1A and 25–1B), with less favored alternatives being excision of aneurysm with interposition graft or aneurysmal vessel reconstruction depending on the aneurysm configuration (Figures 25–1C and 25–1D). If perforators are involved, then flow remodeling strategies to reduce hemodynamic pressures at the inflow zone may be pursued such as EC-IC bypass with proximal clip (retrograde flow supplying perforators), and less favorably EC-IC bypass with distal clip, which may be supplemented with additional endovascular embolization as needed (Figures 25–1E through 25–1G). Intraoperative angiography can be helpful in determining the optimal configuration of flow remodeling. Various techniques for IC-IC bypass with aneurysm trapping have also been described.14,15 At least the following additional factors are also considered for therapeutic selection: overall medical condition and age of the patient along with anatomic extent of the fusiform segment. Diffuse extent of fusiform aneurysms may preclude a focused surgical therapy and warrant conservative management with observation and possibly antiplatelet or anticoagulation agents to reduce risk of thromboembolic phenomena related to turbulent flow (Figures 25–2A through 25–2C).

Acute traumatic arterial dissection involving a focal M1 segment is rare, but if the resulting fusiform aneurysm with dissected flap demonstrates significant flow limitation, associated pseudoaneurysm, or rupture in a patient whose overall medical condition would tolerate invasive therapies, options include surgical trapping with bypass, endovascular takedown with bypass, or endovascular reconstruction. EC-IC bypass followed by proximal surgical occlusion alone without distal trapping may result in reversal of blood flow in the M1 segment with preserved flow to the M1 perforators while helping the dissection subside due to the direction of orientation of the dissected flap.16 Surgical trapping may alternatively be accomplished in conjunction with a purely intracranial IC-IC bypass.14,15 Endovascular takedown with EC-IC bypass may be a more attractive option if the fusiform segment involves the distal internal carotid artery near the skull base in addition to the M1 segment (with ipsilateral anterior cerebral artery having potential contralateral collateral supply via the anterior communicating artery), but surgical therapy may still be achieved in this scenario.17 Reconstructive endovascular options may include flow diverting stent placement, self-expandable stent-within-stent placement, and stent with balloon-assisted coiling.18

Giant MCA bifurcation aneurysms

Patients with giant MCA bifurcation aneurysms may present with mass effect, seizures, ischemic symptoms, stroke, rupture with subarachnoid hemorrhage, or as an incidental finding. For giant MCA bifurcation aneurysms of saccular or fusiform morphology, the configuration of the bifurcation or trifurcation on imaging should help determine how to best preserve the M2 branches. The surgical option of simply clipping the neck of the aneurysm and preserving the direct flow from the M1 trunk to the M2 branches may be precluded by calcified atheromatous base, thick walls with giant wide neck, extensive thrombosis, or anatomic configuration of the M2 origins. Booster clips or a complex combination of clips may be required to achieve clipping of giant aneurysms, and the use of a vascular clamp for assistance has also been described.19 Alternatively, surgical or endovascular obliteration may be performed with or without bypass.20,21

If the anatomic configuration is amenable, EC-IC bypass may be performed to one nonsalvageable M2 branch and clipping can then be performed across the aneurysm neck along with this revascularized M2 origin, while flow may be preserved from the M1 segment to the other salvageable M2 trunk.22 If the giant MCA bifurcation aneurysm is to be excised instead of clipped, the bifurcation can still be microsurgically reconstructed with similar methods.23,24 An analogous reconstruction option can include excision of the giant MCA bifurcation aneurysm with end-to-end anastomosis of the remaining M1 segment to one M2 trunk and performing STA-MCA bypass to the other M2 trunk.25 Sometimes EC-IC or IC-IC bypass may be done to a dominant inferior (or superior) segment if the other bifurcation branch provides minimal supply or has already suffered significant previous infarct with minimal preservable cerebral tissue to salvage in that region. For large or giant MCA aneurysms distal to the bifurcation, surgical trapping may similarly be performed with possible EC-IC bypass or end-to-end anastomosis.26

Distal MCA infectious aneurysms

Patients with distal MCA infectious aneurysms may present with inflammatory symptoms and signs including bacteremia with possible sepsis, congestive heart failure, septic emboli with infarcts of the brain or other organs, rupture with subarachnoid hemorrhage, or as an incidental finding. As previously mentioned, distal infectious aneurysms are often associated with infective endocarditis and cardiac valvular disease, which should optimally be co-managed with infectious disease and cardiac specialists. The natural history of infectious intracranial aneurysms is not fully understood, although there appears to be a relatively high risk of rupture confounded by the fact that cerebrovascular imaging tends to be done for patients who are symptomatic and have high pre-test probability of mycotic aneurysms and septic emboli. It may be prudent to perform screening cerebral CTA on patients with new diagnosis of infective endocarditis or prior to cardiac valve repair with plans for possible anticoagulation for the procedure that could potentially worsen the consequences of an aneurysm rupture. When infectious cerebral aneurysms are noted in coexistence with severe cardiac valvular disease, it may be challenging to determine the optimum timing of whether treatment of the aneurysm versus cardiac valve repair should be undertaken first.27,28 Cardiac valve repair has been reported without anticoagulation in the context of a ruptured infectious aneurysm and conservative management of the aneurysm with antimicrobials, having improvement in the aneurysm over several months.29

Patients who have <5-mm, unruptured distal MCA infectious aneurysms may be considered for expectant conservative management with antimicrobials but should have serial follow-up imaging (such as CTA) every few weeks or months, with consideration for invasive treatment within the first several months if the aneurysm demonstrates lack of improvement or worsening (such as growth or rupture). Patients in moribund condition may also be considered for conservative treatment regardless of aneurysmal configuration. Patients in poor overall medical condition but ruptured or larger distal MCA infectious aneurysms may be considered for endovascular Onyx or coil embolization, depending on the aneurysmal configuration. If the patient is in reasonable overall medical condition, surgical or endovascular trapping may be considered regardless of the size or rupture status of the infectious aneurysm. This may be performed without bypass if the distal MCA branches supply minor or noneloquent cerebral regions, or EC-IC versus IC-IC bypass may be performed if the angular branch on the dominant side or other important distal branches are involved. If the aneurysmal configuration is amenable, direct surgical clipping may even be feasible as a preferred option, but more commonly the configuration requires proximal and distal trapping with possible excision of the infectious aneurysm.30 If it is unclear whether the involved distal MCA branches supply functionally important cerebral tissues, awake craniotomy may be undertaken for temporary clipping to determine if surgical trapping may be tolerated without EC-IC or IC-IC bypass, which can be performed in a minimally invasive fashion when used in conjunction with image-guidance systems.31

Challenging issues include the presence of multiple mycotic aneurysms, which may be more amenable to a single or staged endovascular interventional combination, especially if the locations are bilateral or involve the posterior circulation, although staged surgical treatment may still be feasible in select cases.32 Involved branching or various bifurcation points can be microsurgically reconstructed in theory, but there is a potential risk of delayed pseudoaneurysm formation at the bifurcation site, such that end-to-end anastomosis of the proximal MCA to one of the distal MCA branches (with graft if needed) used in conjunction with EC-IC bypass to the other distal MCA branch is the preferred reconstruction option.

Surgical technique

I Donor Evaluation

Donor vessel options include the STA, radial artery, greater saphenous vein graft, and cadaveric vein graft.33,34 The sites of the ipsilateral STA, bilateral radial arteries, and bilateral greater saphenous veins should be assessed on physical exam with noting of any past surgical history involving those vessels, and portions of the STA can also be assessed on cranial vascular imaging studies. Alternatively, in situ IC-IC bypass may be an option depending on the individual anatomic configuration, which can also be assessed on imaging. IC-IC bypasses such as an in situ MCA-MCA bypass may have the advantages of having caliber-matched donor and recipient arteries along with being a relatively short graft that remains protected inside the cranium postoperatively.15,22

Donor vessels require a diameter of at least >1 mm with matching of donor-recipient size facilitating an optimal anastomosis. Although there can be great variability in the same donor vessels between individuals, there is debate that a STA-MCA graft provides a low-flow bypass, long arterial graft provides an intermediate-flow bypass, and a long venous graft bypass provides a high-flow bypass.35,36 As previously mentioned, anastomotic options involve STA to MCA end-to-side or end-to-end bypass, radial artery ECA-MCA bypass, in situ MCA-MCA bypass, reversed saphenous vein graft ECA-MCA bypass, or reversed cadaveric vein graft ECA-MCA bypass. A standard STA-MCA bypass consists of end-to-side or end-to-end anastomosis of a branch of the STA to a selected MCA branch in the region of the Sylvian fissure. Radial artery ECA-MCA bypass involves harvesting the radial artery (usually from the side of the nondominant hand) using open or endoscopic techniques33; Allen’s test has poor predictive value for evaluating collateral flow and the ulnar artery of the donor arm should not have any history of previous injury or surgery. In situ IC-IC bypass may involve MCA-MCA bypass from the anterior temporal artery to another M2 branch, reimplantation of an M2 trunk onto another M2 trunk, or other methods of direct MCA to MCA bypass depending on individual anatomy.14,15 Saphenous vein graft ECA-MCA bypass may be done using autologous saphenous interposition vein graft taken from either leg (if sites have not previously been used for coronary artery or peripheral vascular disease). If neither saphenous vein nor other autologous site is desirable, then cadaveric vein graft may be used for ECA-MCA bypass.

IV STA-MCA Anastomosis

Intraoperative monitoring with electroencephalography and evoked potentials may optionally be used. An operating microscope should be used for optimal anastomosis. Papaverine local application may be used to minimize vasospasm. Flow-probe monitoring may be used after bypass to assess flow,37 and intraoperative cerebral angiography may be used to assess bypass patency and hemodynamic configuration. The use of laser contrast analysis has also been reported.38

Case Example

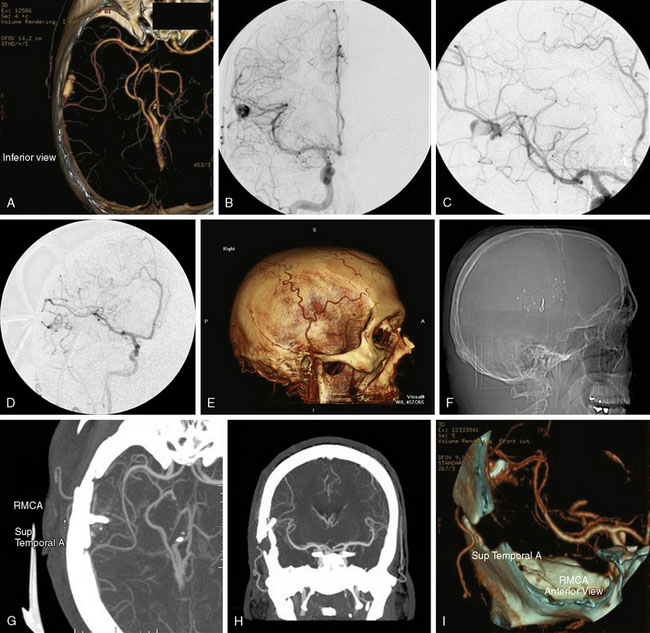

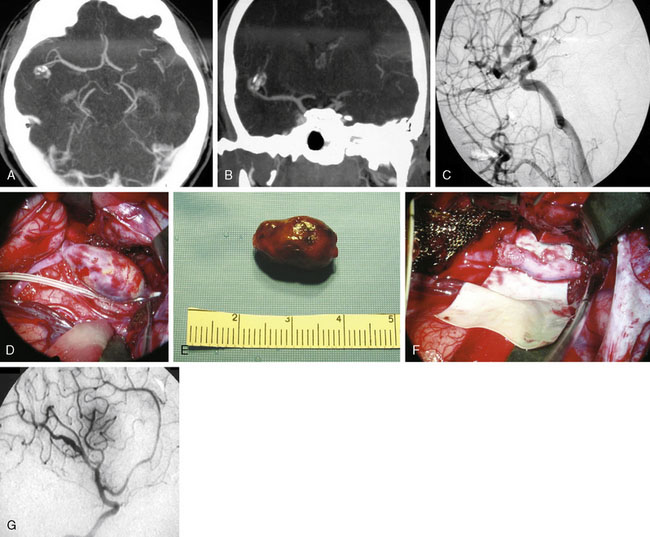

The surgical technique for standard right STA-MCA bypass with surgical trapping for a right distal M3/M4 infectious aneurysm is described, with similar general principles applicable for EC-IC bypass approaches for M1 fusiform aneurysms and giant MCA bifurcation aneurysms. A 36-year-old male with a history of Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis status post-antibiotic treatment and post-mitral valve replacement (29-mm Bjork-Shiley prosthetic valve) 19 years prior on chronic Coumadin (INR goal maintained at 2 to 3) presented with gradual onset headaches for 3 months. He reportedly had distant history of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia with seeding of the mitral valve at age 17 with source unclear and denied any history of intravenous drug use. His past medical history was otherwise only notable for L4-L5 discectomy and laminectomy with posterior spinal fusion (L4-L5 pedicle screws and rods) and transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion 3 years prior followed by removal of segmental spinal instrumentation 2 years prior after bony fusion (for low back pain and left hip pain since resolved) for which he had been off construction work for the past 4 years. CTA showed a 16-mm AP x 7-mm TV x 6-mm SI bilobed aneurysm arising from a Sylvian branch of the superior division of the right MCA (Figure 25–3A), which was suspicious for a mycotic aneurysm, but radiology read suggested differential diagnosis of arteriovenous malformation (AVM) not being completely excluded. Therefore, a follow-up DSA was done that also included selective right ECA and ICA injections that confirmed the 16-mm AP x 7-mm TV x 6-mm irregular multilobulated aneurysm with partially fusiform and partially saccular configuration involving an M3/M4 junction of a distal branch of the right MCA superior division with two M4 branches projecting superior-posteriorly and inferior-posteriorly from the body of the aneurysm (Figures 25–3B and 25–3C). A prominent right ECA with right STA for potential EC-IC bypass was noted, and there was no evidence for associated AVM.

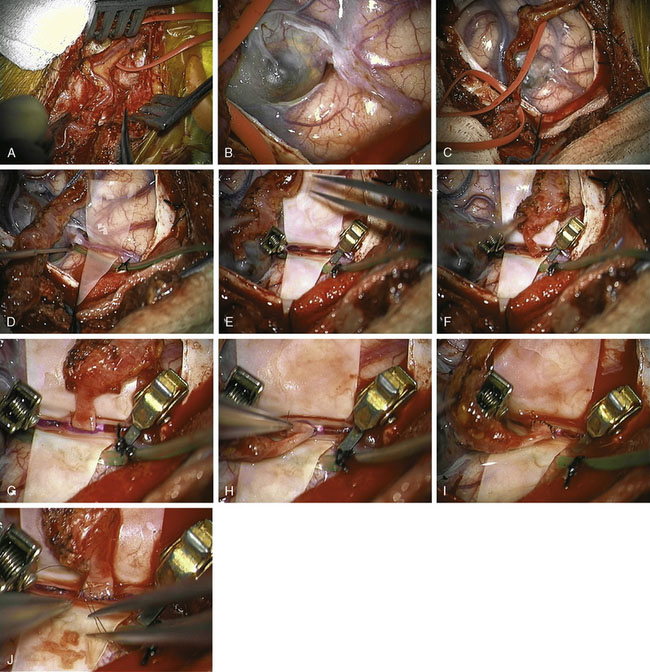

The patient was taken for right temporal craniotomy for microsurgical right STA-MCA bypass with proximal occlusion of the complex distal right MCA aneurysm using the operative microscope, stereotactic image-guidance system, and intraoperative cerebral angiography (Figures 25–3D through 25–3I). The patient underwent general anesthesia, right common femoral artery sheath was placed for intraoperative angiography access with integration into the craniotomy sterile draping, the patient’s head was turned to the left, and the right superficial temporal artery was mapped using a microvascular Doppler probe. The right parietal-temporal region was prepped and draped in a sterile fashion. After the skin incision, an operating microscope was used to dissect and isolate the right STA using pencil-tip monopolar cautery, scissors and ligation. The artery was dissected along its length from the superior border of the zygoma to its distal end at the right parietal region. Red vascular loops were used to wrap around and isolate the right STA with circumferential dissection (Figure 25–4A). The right STA was retracted anteriorly and posteriorly to open the temporalis muscle layer deep to this region with Gelpi retractor.

The stereotactic image-guidance system was then used to confirm the location of the complex right MCA aneurysm, which was located just superior to the level of the ear and within the planned craniotomy. Four burr holes were placed around the planned craniotomy with curettes used to remove the inner table, and a #3 Penfield dissector was used to separate the dura from the inner surface of the skull. The craniotome was used to connect the burr holes into a rectangular-shaped bone flap, which was then removed. The dura was opened and reflected anteriorly, revealing the partially thrombosed distal right MCA aneurysm on the surface of the brain (Figure 25–4B).

Using the operating microscope, dissection was performed circumferentially around the MCA aneurysm with dissection around the efferent vessels leaving the lesion and afferent vessel entering the lesion, consistent in appearance with the CTA and DSA. A patty was placed on the proximal end to prepare for proximal control in case rupture should occur (Figure 25–4C), and then attention was turned to the distal vessels with bipolar coagulation of two small perforators associated with the branch vessel. The aneurysm target was isolated on a rubber dam stage with placement of a microsuction device below the stage to provide constant suction for the bypass procedure and intermittent irrigation with heparinized saline (Figure 25–4D). The STA was cleaned at the site for the planned anastomosis using two 5-O jeweler’s forceps and then straight microscissors. A temporary clip was placed proximal and distal to the planned anastomotic site along the STA, and then the STA was transected at a slight angle and brought to the prepared donor site on the rubber dam stage. The MCA branch was occluded proximally and distally with temporary clips (Figure 25–4E), and the donor site was incised linearly with an arachnoid knife to form an end-to-side, STA-to-MCA anastomosis with the STA angled slightly towards the angle of desired flow of the anastomosis (Figure 25–4F). A 9-O nylon suture was used to tack two sides of the graft into position (Figures 25–4G and 25–4H), the graft was flipped and six interrupted sutures were placed to connect the back side, and then the graft was rotated back and six interrupted sutures were placed to connect the front side (Figures 25–4I and 25–4J). Clamps were released with one leak site at the anastomosis noted for which the clamps were reapplied with one additional suture placed at the leak site. The clamps were again removed, and excellent flow was observed through the STA graft into the distal MCA vessels as confirmed using microvascular Doppler probe.

A J-shaped aneurysm clip was then placed on the afferent vessel entering the aneurysm for proximal occlusion, and then intraoperative focused cerebral angiography was performed. Intraoperative focused cerebral angiography with right common carotid artery injection showed patent right STA (posterior branch) with end-to-side anastomotic bypass to a right distal MCA (M4) branch that continued to fill further distal MCA branches, with no filling of the complex right MCA aneurysm following surgical trapping (see Figure 25–3D). At the Y-shaped junction, it was known that there was a second efferent vessel adjacent to the vessel that received bypass, which were both in close proximity to the aneurysm. Attempts for distal occlusion of the aneurysm would force the clip onto the branch vessels, and the alternative of opening the aneurysm and cleaning out the edge to place the clip without compromising the branch vessels was felt to be a higher potential risk than benefit given that the intraoperative angiography showed that the aneurysm was no longer filling with the current operative configuration. If the intraoperative angiography had shown continued filling of the aneurysm, then distal occlusion would have been pursued by placing temporary distal clips and opening the aneurysm to clean out the edge to allow the aneurysm clip to sit securely on the distal site. The patient remained neurologically intact immediately after surgery and at his 5-month follow-up visit.

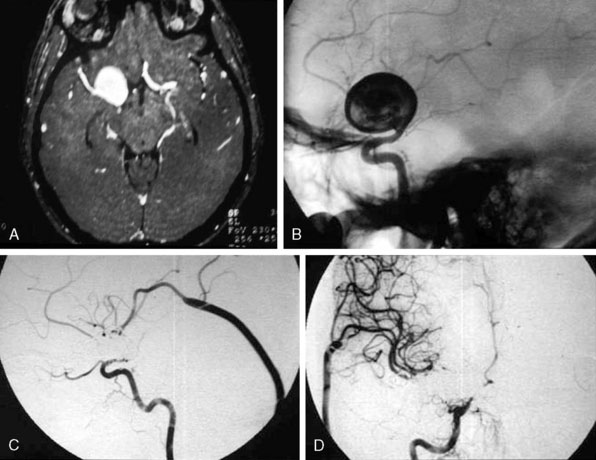

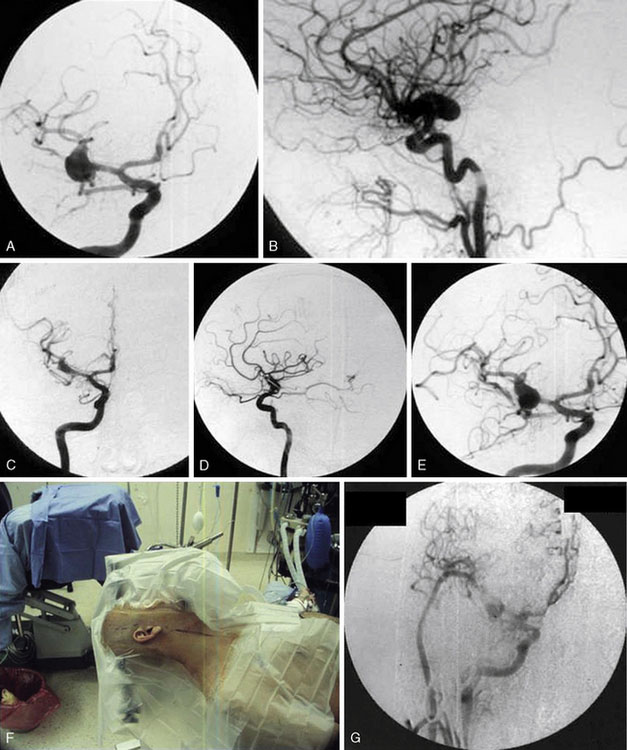

Additional case examples are illustrated: EC-IC bypass with distal clip and coil embolization for a giant right fusiform M1 aneurysm (Figures 25–5A through 25–5D), vessel reconstruction with partial clip obliteration of giant fusiform M1 aneurysm involving the right MCA bifurcation having regrowth at 2 years postoperatively for which EC-IC bypass for flow remodeling using saphenous vein graft was done (Figures 25–6A through 25–6G), and distal infectious aneurysm along the right MCA inferior division treated with aneurysm excision and saphenous vein interposition graft (Figures 25–7A through 25–7G).

Potential complications

Potential risks and complications include graft thrombosis, anastomotic leak, hemorrhage, stroke, vasospasm, seizures, cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) leak, pseudoaneurysms involving the bypass, aneurysm recurrence, and wound infections. Series of EC-IC bypass grafts in complex aneurysms generally quote patency rates over 84% with mortality less than 10%.36,39,40 Care must also be taken that the patient avoids wearing compressive glasses, tight hats, or other headwear that would potentially compress and compromise EC-IC graft patency. Early compromise of the bypass graft may be surgically re-explored with thrombectomy or re-anastomosis, intraoperative prophylactic mechanical or topical medication techniques may be used for minimizing vasospasm, endovascular therapies may be attempted for delayed vasospasm, and consideration of new therapeutic approaches need to be devised if pseudoaneurysms involving the bypass graft or recurrence of aneurysm occurs at follow-up.

1 Park S.H., Yim M.B., Lee C.Y., et al. Intracranial fusiform aneurysms: its pathogenesis, clinical characteristics and managements. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2008;44:116-123.

2 Amin-Hanjani S., Butler W.E., Ogilvy C.S., et al. Extracranial-intracranial bypass in the treatment of occlusive cerebrovascular disease and intracranial aneurysms in the United States between 1992 and 2001: a population-based study. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:794-804.

3 Aoki S., Sasaki Y., Machida T., et al. Cerebral aneurysms: detection and delineation using 3-D-CT angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1992;13:1115-2110.

4 Hoh B.L., Cheung A.C., Rabinov J.D., et al. Results of a prospective protocol of computed tomographic angiography in place of catheter angiography as the only diagnostic and pretreatment planning study for cerebral aneurysms by a combined neurovascular team. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:1329-1340.

5 Napel S., Marks M.P., Rubin G.D., et al. CT angiography with spiral CT and maximum intensity projection. Radiology. 1992;185:607-610.

6 Hoh B.L., Putman C.M., Budzik R.F., et al. Combined surgical and endovascular techniques of flow alteration to treat fusiform and complex wide-necked intracranial aneurysms that are unsuitable for clipping or coil embolization. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:24-35.

7 Chen L., Kato Y., Sano H., et al. Management of complex, surgically intractable intracranial aneurysms: the option for intentional reconstruction of aneurysm neck followed by endovascular coiling. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;23:381-387.

8 Song D.L., Leng B., Zhou L.F., et al. Onyx in treatment of large and giant cerebral aneurysms and arteriovenous malformations. Chin Med Journal. 2004;117(12):1869-1872.

9 Hoh B.L., Carter B.S., Putman C.M., et al. Important factors for a combined neurovascular team to consider in selecting a treatment modality for patients with previously clipped residual and recurrent intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:732-738.

10 Karnchanapandh K., Imizu M., Kato Y., et al. Successful obliteration of a ruptured partially thrombosed giant m1 fusiform aneurysm with coil embolization at distal m1 after extracranial-intracranial bypass. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2002;45:245-250.

11 Nakatomi H., Segawa H., Kurata A., et al. Clinicopathological study of intracranial fusiform and dolichoectatic aneurysms. Stroke. 2000;31:896.

12 Yonekawa Y., Zumofen D., Imhof H.G., et al. Hemorrhagic cerebral dissecting aneurysms: surgical treatments and results. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2008;103:61-69.

13 Flemming K.D., Wiebers D.O., Brown R.D.Jr, et al. The natural history of radiographically defined vertebrobasilar nonsaccular intracranial aneurysms. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;20:270-279.

14 Lawton M.T., Zador Z.E., Lu D. Current strategies for complex aneurysms using intracranial bypass and reconstructive techniques. Jpn J Neurosurg (Tokyo). 2008;17:601-611.

15 Sanai N., Zador Z., Lawton M.T. Bypass surgery for complex brain aneurysms: as assessment of intracranial-intracranial bypass. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:670-683.

16 Takeo G., Kenji O., Akimasa N., et al. Treatment of a fusiform middle cerebral artery aneurysm at M1 part which cause cerebral infarction at its perforating area: a case report. Surg Cerebral Stroke. 2006;34:59-63.

17 Ferroli P., Ciceri E., Parati E., et al. Obliteration of a giant fusiform carotid terminus-M1 aneurysm after distal clip application and extracranial-intracranial bypass. Case report. J Neurosurg Sci. 2007;51:71-76.

18 Lubicz B., Collignon L., Lefranc F., et al. Circumferential and fusiform intracranial aneurysms: reconstructive endovascular treatment with self-expandable stents. Neuroradiology. 2008;50:499-507.

19 Navratil O., Lehecka M., Lehto H., et al. Vascular clamp-assisted clipping of thick-walled giant aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:113-120.

20 Carter B.S., Ogilvy C.S., Putman C., et al. Selective use of extracranial-intracranial bypass as an adjunct to therapeutic internal carotid artery occlusion. Clin Neurosurg. 2000;46:351-362.

21 Shi Z.S., Ziegler J., Duckwiler G.R., et al. Management of giant middle cerebral artery aneurysms with incorporated branches: partial endovascular coiling or combined extracranial-intracranial bypass–a team approach. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:121-129.

22 Seo B.R., Kim T.S., Joo S.P., et al. Surgical strategies using cerebral revascularization in complex middle cerebral artery aneurysms. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2009;111(8):670-675.

23 Bojanowski W.M., Spetzler R.F., Carter L.P. Reconstruction of the MCA bifurcation after excision of a giant aneurysm. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:974-977.

24 Ceylan S., Karakus A., Duru S., et al. Reconstruction of the middle cerebral artery after excision of a giant fusiform aneurysm. Neurosurg Rev. 1998;21:189-193.

25 Zhou L.F., Jiang D.J. Cerebral artery reconstruction in the treatment of large and giant intracranial aneurysms. Chin Med J (Engl). 1994;107:41-46.

26 El Beltagy M., Muroi C., Imhof H.G., et al. Peripheral large or giant fusiform middle cerebral artery aneurysms: report of our experience and review of literature. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2008;103:37-44.

27 Tsutsumida H., Nakamura K., Matsuzaki Y., et al. A case of heart operation in infective endocarditis after brain surgery for mycotic cerebral aneurysm. Kyobu Geka. 2000;53:229-232.

28 Uchino T., Hirayama T., Ishikawa M., et al. A case report of early valve replacement surgery in infective endocarditis with mycotic cerebral aneurysm. Nippon Kyobu Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1989;37:2025-2028.

29 Shiraishi Y., Awazu A., Harada T., et al. Valve replacement in a patient with infective endocarditis and ruptured mycotic cerebral aneurysm. Nippon Kyobu Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;40:118-123.

30 Nakahara I., Taha M.M., Higashi T., et al. Different modalities of treatment of intracranial mycotic aneurysms: report of 4 cases. Surg Neurol. 2006;66:405-409.

31 Luders J.C., Steinmetz M.P., Mayberg M.R. Awake craniotomy for microsurgical obliteration of mycotic aneurysms: technical report of three cases. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:E201.

32 Kuki S., Yoshida K., Suzuki K., et al. Successful surgical management for multiple cerebral mycotic aneurysms involving both carotid and vertebrobasilar systems in active infective endocarditis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1994;8:508-510.

33 Ferroli P., Bisleri G., Miserocchi A., et al. Endoscopic radial artery harvesting for U-clip high-flow EC-IC bypass: technical report. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2009;151:529-535.

34 Mery F.J., Amin-Hanjani S., Charbel F.T. Cerebral revascularization using cadaveric vein grafts. Surg Neurol. 2009;72:362-368.

35 Kocaeli H., Andaluz N., Choutka O., et al. Use of radial artery grafts in extracranial-intracranial revascularization procedures. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;24:E5.

36 Scamoni C., Dario A., Castelli P., et al. Extracranial-intracranial bypass for giant aneurysms and complex vascular lesions: a clinical series of 10 patients. J Neurosurg Sci. 2008;52:1-9.

37 Charbel F.T., Hoffman W.E., Misra M., et al. Role of a perivascular ultrasonic micro-flow probe in aneurysm surgery. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1998;38:35-38.

38 Hecht N., Woitzik J., Dreier J.P., et al. Intraoperative monitoring of cerebral blood flow by laser speckle contrast analysis. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;27:E11.

39 Cantore G., Santoro A., Guidetti G., et al. Surgical treatment of giant intracranial aneurysms: current viewpoint. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:279-289.

40 Sekhar L.N., Duff J.M., Kalavakonda C., et al. Cerebral revascularization using radial artery grafts for the treatment of complex intracranial aneurysms: techniques and outcomes for 17 patients. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:646-658.