10 Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy

Note 1: This book is written to cover every item listed as testable on the Entry Level Examination (ELE), Written Registry Examination (WRE), and Clinical Simulation Examination (CSE).

The listed code for each item is taken from the National Board for Respiratory Care’s (NBRC) Summary Content Outline for CRT (Certified Respiratory Therapist) and Written RRT (Registered Respiratory Therapist) Examinations (http://evolve.elsevier.com/Sills/resptherapist/). For example, if an item is testable on both the ELE and the WRE, it will simply be shown as: (Code: …). If an item is only testable on the ELE, it will be shown as: (ELE code: …). If an item is only testable on the WRE, it will be shown as: (WRE code: …).

MODULE A

1. Recommend starting bronchopulmonary hygiene procedures (Code: IIIG1a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

2. Instruct and encourage bronchopulmonary hygiene techniques (Code: IIIC4) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

Teach the patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease the following cough techniques:

Coaching is important because patients in pain or suffering from chronic lung disease tend to be uncooperative and do not try hard. Give positive reinforcement when the patient does well. Correct any problems the patient is having following the instructions. Demonstrations are often useful so that the patient can copy a good example.

If the patient cannot cough effectively, other secretion clearance procedures will be needed. Postural drainage therapy (PDT) and other procedures follow. The American Association for Respiratory Care (AARC) Clinical Practice Guideline on PDT was used to help develop the following information. See Box 10-1 for indications for turning, postural drainage, percussion, and vibration. Contraindications are listed in Box 10-2, and recommended actions for problems are listed in Box 10-3. Beyond the patient assessment issues listed in Box 10-4, the following should be evaluated to determine whether PDT is needed:

BOX 10-1 Indications for Turning, Postural Drainage, and Percussion and Vibration

Based on information found in American Association for Respiratory Care: Clinical practice guideline: postural drainage therapy, Respir Care 36:1418, 1991.

TURNING

BOX 10-2 Contraindications for Turning/Postural Drainage and Percussion and Vibration

Based on information found in American Association for Respiratory Care: Clinical practice guideline: postural drainage therapy, Respir Care 36:1418, 1991.

TURNING/POSTURAL DRAINAGE*

All positions are contraindicated for patients with the following:

Trendelenburg position is contraindicated in patients with the following:

Reverse Trendelenburg position is contraindicated in patients who are:

Based on information found in American Association for Respiratory Care: Clinical practice guideline: postural drainage therapy, Respir Care 36:1418, 1991.

HAZARDS/COMPLICATIONS

BOX 10-4 Assessment of the Patient’s Needs for Postural Drainage Therapy (PDT)*

Based on information found in American Association for Respiratory Care: Clinical practice guideline: postural drainage therapy, Respir Care 36:1418, 1991.

3. Perform postural drainage (Code: IIIC1a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

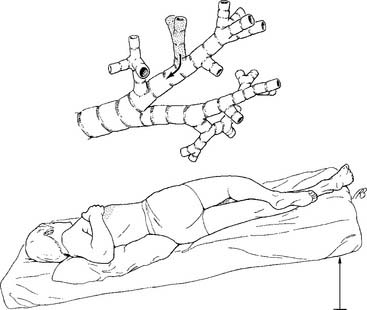

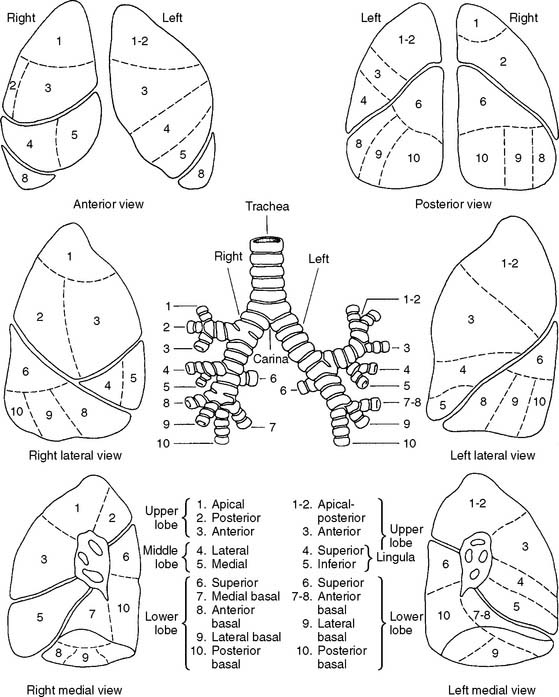

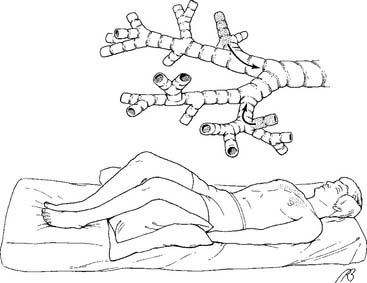

Postural drainage (bronchopulmonary drainage) is performed to clear secretions or prevent the accumulation of secretions. The patient is positioned so that the bronchus of a particular segment is as vertical as possible. Gravity pulls the secretions toward a major bronchus or the trachea; the secretions are then either expectorated or suctioned. The anatomy of the pulmonary lobes with their segments and respective bronchi should be reviewed (Figure 10-1).

Figure 10-1 Names and locations of the lung segments and their respective bronchi.

(From Shibel EM, Moser KM, editors: Respiratory emergencies, St Louis, 1977, Mosby.)

Coughing should be encouraged after each segment is drained. The patient should not cough in a head-down position, however, because of the risk of increased intracranial pressure. Have the patient sit up to cough vigorously.

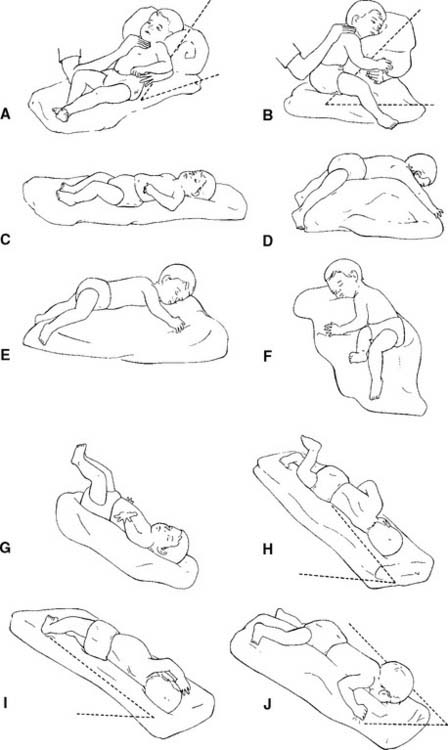

a. Pulmonary drainage positions

1. Lower lobes

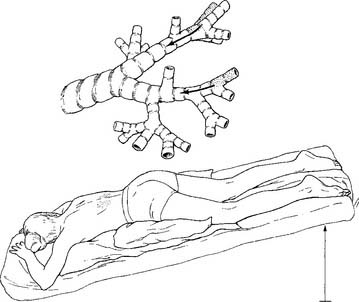

a. Posterior basal segment (Figure 10-2)

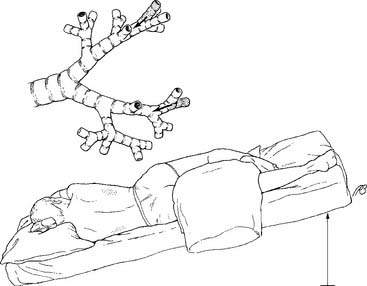

b. Lateral basal segment (Figure 10-3)

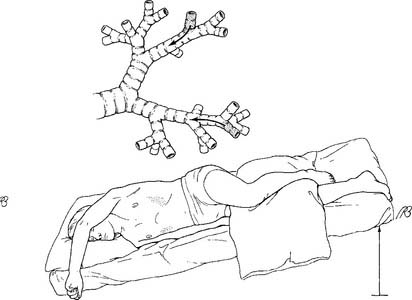

c. Anterior basal segment (Figure 10-4)

2. Right middle lobe and left lingula

a. Right lateral and medial segments (Figure 10-6)

b. Left superior and inferior lingula segments (Figure 10-7)

3. Upper lobes

a. Posterior segment (Figure 10-8)

b. Apical segment (Figure 10-9)

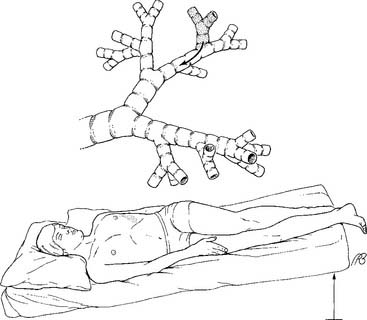

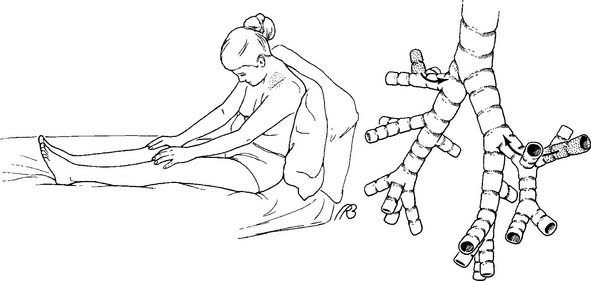

c. Anterior segment (Figure 10-10)

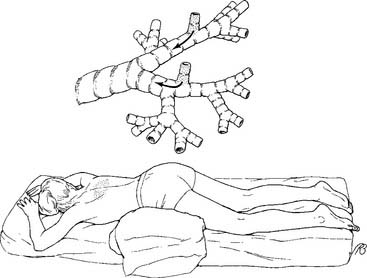

Figure 10-10 Drainage position for the anterior segments of both upper lobes.

(From Eubanks DH, Bone RC: Comprehensive respiratory care, ed 2, St Louis, 1990, Mosby.)

Some authors may list slightly different positions or several additional positions. The most commonly accepted postural drainage positions have been presented. The postural drainage positions in the infant are basically the same as those in the adult. Positioning can be accomplished more easily by using pillows. Figure 10-11 shows the various segmental drainage positions.

The examination usually contains at least one question that deals with knowing the correct position to drain a particular lobe. The lower lobes are usually tested. The question may give information on an opaque area seen on the chest radiograph. The therapist is expected to know what segment or lobe needs to be drained. Review Figure 1-8 for a drawing showing areas of consolidation.

4. Perform percussion (Code: IIIC1a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

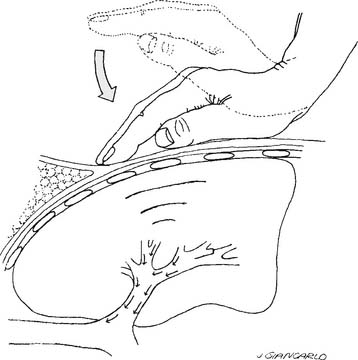

Percussion (also known as clapping, cupping, and tapotement) is the act of rhythmically striking the adult patient’s chest with cupped hands over an area with secretions. A properly cupped hand traps air against the chest and causes a popping sound. The wrists, elbows, and shoulders should be kept as loose as possible to enable the practitioner to keep the proper loose waving motion of the hand and minimize fatigue (Figure 10-12). Infants can be percussed by putting the index, middle, and ring fingers together into a kind of three-sided tent, or specially designed palm cups. This enables the practitioner to percuss a small area of the chest wall. Percussion is performed throughout the breathing cycle and can be done with one or both hands. Percussion should not be painful to the patient. As an added precaution, most authors recommend that the chest be covered lightly with the patient’s gown or towel. Percussion should not be done over buttons or zippers or female breast tissue.

5. Perform vibration (Code: IIIC1a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

Vibration is the gentle, rapid shaking of the chest wall directly over the lung segment that is being drained. It may be performed alone or with percussion. The practitioner places his or her hands side by side if the chest area is large enough or one on the other for a smaller chest area. The elbows are locked with the arms straight (Figure 10-13). The patient’s chest is gently but effectively shaken during exhalation. The patient should exhale at least the complete tidal volume (VT) as the chest wall is vibrated. Blowing out the expiratory reserve volume should help to clear out more secretions. A vibration rate of 200 per minute (about 3 per second) has been recommended as ideal to help move secretions. The literature differs as to how the patient should exhale during the procedure. Both breathing out slowly through pursed lips and breathing out forcefully through an open mouth have been recommended. A pursed-lip exhalation pattern seems reasonable if the patient has a problem with bronchospasm and air trapping. A patient without this problem should exhale forcefully because this helps to clear more secretions. Vibration should be performed for several expiratory efforts or until it is no longer effective in helping to mobilize secretions.

6. Modify the postural drainage therapy (ELE code: IIIF2f1) [ELE difficulty: R, Ap, An]

b. Change the treatment techniques used.

d. Change the postural drainage therapy position based on the patient’s response.

Some patients cannot tolerate being properly positioned because their underlying lung or heart disease is aggravated by the unnatural body position. This is most commonly seen in the head-down positions to drain the lower lobes. Watch for signs of hypoxemia and SOB. The patient may have to be placed in a better-tolerated but less-desirable position. As long as some downward angle to the bronchus exists, mucus will drain. Each patient must be evaluated on an individual basis.

7. Coordinate the sequence of bronchial hygiene therapies: postural drainage, percussion, vibration, and positive expiratory pressure (ELE code: IIIF2f2) [ELE difficulty: R, Ap, An]

8. Stop the treatment if the patient has an adverse reaction to it (Code: IIIF1) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

Be prepared to stop the treatment if the patient has an adverse reaction. Often this results when a patient is placed into a head-down position. Review Box 10-3 for hazards and complications of postural drainage, percussion, and vibration.

9. Manipulate postural drainage therapy equipment by order or protocol: percussors and vibrators (ELE code: IIA14a) [Difficulty: R, Ap, An]

a. Get the necessary equipment for the procedure.

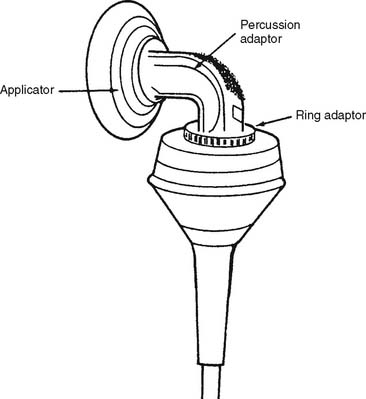

The terms percussor and vibrator are sometimes used interchangeably. Several manufacturers produce either electrically or pneumatically powered percussors/vibrators. Some are large enough to be wheeled into the patient’s room (Figure 10-14). Obviously, electrically powered units need a standard electrical outlet for power, and the pneumatically powered units must be plugged into a 50-psi O2 or air source.

b. Put the equipment together and make sure that it works properly.

Because various devices are powered by wall electrical output, 50-psi source gas, or batteries, check the power source if the device fails to work. Some units have different patient applicators and connectors. These must be fastened properly so that the vibrating action does not cause them to loosen or fall off. For example, the Vibramatic/Multimatic has several patient applicators that must be screwed into the percussion adapter, which is then screwed into the ring adapter (Figure 10-15).

Some electrically powered units use a rubber belt and different sized wheels to change gears and produce several vibration rates. Others electrically vary the motor speed to change the vibration rate. Some pneumatically driven units can have their percussion force and rate varied.

MODULE B

Box 10-5 lists indications for PEP therapy. In patients with air trapping because of small airways disease (asthma or COPD), PEP therapy acts like pursed-lips breathing to keep the small airways from collapsing. This allows the trapped alveolar gas to be more completely exhaled. Patients with atelectasis, or at risk for developing atelectasis, respond well to PEP therapy if incentive spirometry is not effective. PEP seems to push air through the Kohn pores of open alveoli into adjacent areas of atelectasis to force the alveoli open. There is evidence that PEP therapy is better than incentive spirometry (IS) or intermittent positive pressure breathing (IPPB) in the treatment of patients with postoperative atelectasis.

BOX 10-5 Indications for Positive Expiratory Pressure Therapy

Box 10-6 lists relative contraindications to PEP therapy. No absolute contraindications exist. Box 10-7 lists hazards or complications of PEP therapy. These should be weighed against the benefits to the patient when making the recommendation to start PEP therapy. Other considerations include the patient’s history of pulmonary disease and the response to CPT, ineffective cough to clear retained secretions, and breath sounds and chest radiograph findings of secretions.

BOX 10-6 Relative Contraindications to Positive Expiratory Pressure Therapy

1. Part 1: Adjustable fixed-orifice type PEP device

a. Perform positive expiratory pressure therapy (Code: IIIC1d) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

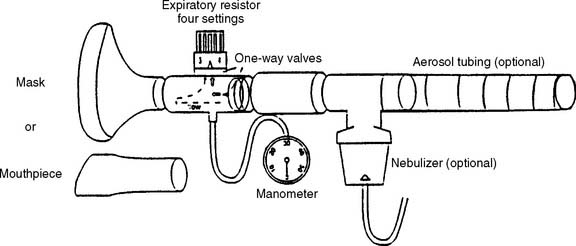

The patient must be old enough to understand instructions and be able to perform the procedure. Box 10-8 lists the steps in performing a proper PEP therapy treatment. Be prepared to adjust the expiratory resistance to meet the clinical goal of PEP therapy. Initially the resistance to exhalation should be kept low. As the training continues, the resistance the patient breathes against can be increased. The goal is to maintain a PEP of 10 to 20 cm H2O with an inspiratory/expiratory (I:E) ratio of about 1 : 3. If the expiratory orifice is too small, the expiratory airway pressure will be too high or the expiratory time too long. The patient will likely become fatigued. If the expiratory orifice is too large, the pressure will not be high enough to be of any benefit. In any situation, the patient will probably become tired if the total treatment time lasts longer than 20 minutes.

BOX 10-8 Steps in Performing Positive Expiratory Pressure (PEP) Therapy

b. Coordinate the sequence of bronchial hygiene therapies: postural drainage, percussion, vibration, and positive expiratory pressure (ELE code: IIIF2f2) [ELE difficulty: R, Ap, An]

Coordinate PEP therapy with effective directed coughing, “huff” cough techniques, CPT, or aerosolized medication delivery. As listed in Box 10-8, PEP breaths can be alternated with huff coughs to clear secretions. Huff coughs are not full, deep coughs; rather, they are performed as follows:

c. Terminate the treatment if the patient has an adverse reaction to it (Code: IIIF1) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

During the treatment, ask the patient if he or she feels dyspnea, pain, or chest discomfort. Also monitor the patient’s breath sounds, blood pressure, heart rate, and breathing pattern and rate. Monitor oxygenation by pulse oximetry, mental clarity, and skin color. Be prepared to stop the treatment if necessary. Review the contraindications listed in Box 10-6 and hazards listed in Box 10-7.

d. Manipulate fixed-orifice PEP therapy equipment by order or protocol (ELE code: IIA14c) [ELE difficulty: R, Ap, An]

1. Get the necessary equipment for the procedure

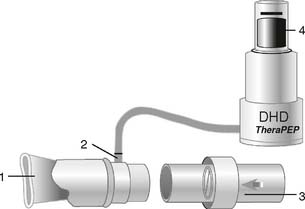

Currently, several positive expiratory pressure (PEP) systems are available for selection, based on the patient’s needs. Figure 10-16 shows the TheraPEP device. The following basic components are included:

The following optional components are included:

Figure 10-17 shows the Resistex unit. Basic components include the following:

Optional components, shown in Figure 10-17, include the following:

2. Put the equipment together and make sure that it works properly

As described previously and shown in Figures 10-16 and 10-17, the component pieces must be gathered and properly assembled. Make sure that all connections are airtight. If a leak is present, the desired PEP goal will not be reached or maintained. In addition, an air leak may be felt or a high-pitched sound may be heard. If an SVN or MDI is added, it must be tested to ensure that it works properly. Connect the SVN (or MDI) into the system, as shown in Figure 10-17. Add the medication and run a flow of O2 or compressed air at 4 to 6 L/min through the nebulizer (as is customary). The slowed exhalation during PEP breathing should promote better deposition of medication into the small airways.

3. Troubleshoot any problems with the equipment

Any leaks in the system will prevent the PEP goal from being reached. Tighten any loose connections. If the one-way valves in the Resistex or TheraPEP units are assembled backward, the patient will inspire against a resistance instead of exhaling against it. Observe the one-way valves in use, and ask the patient if he or she finds it easy to inhale but more difficult to exhale. Move the valves to their proper positions if incorrectly placed. If an SVN is used, check that aerosol is coming from the nebulizer. If not, check the capillary tube or baffle for an obstruction; clear it by running tap water or a sterile needle through it. See Chapter 8, if necessary, for more information on fixing problems with SVNs.

2. Part 2: Adjustable vibratory-type PEP device

a. Perform vibratory positive expiratory pressure therapy (Code: IIIC1d) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

The NBRC refers to this type of PEP therapy as vibratory PEP. However, since the professional literature refers to it as oscillatory PEP or OPEP, that terminology will be used here. OPEP has the same indications (Box 10-5), contraindications (Box 10-6), hazards (Box 10-7), and clinical benefits as PEP delivered through a fixed-orifice resistor. In theory, the airway oscillations produced with OPEP improve airway clearance better than PEP. However, this has not been proven in clinical trials. Two widely known OPEP devices will be presented here. Box 10-9 will present the basic steps in performing an OPEP treatment. Other general considerations for OPEP and related therapies are the same as those for PEP and were presented previously.

BOX 10-9 Steps in Performing Oscillatory Positive Expiratory Pressure (OPEP) Therapy

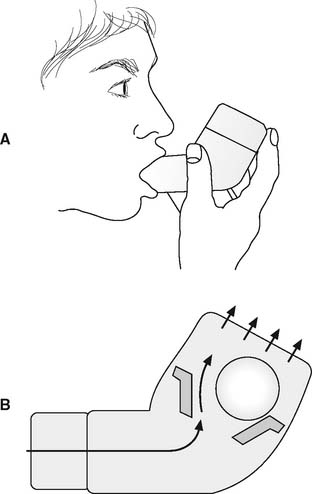

Of all the OPEP devices, the Flutter (Figure 10-18) has been used the most, primarily with cystic fibrosis patients. Because of its simplicity, both small children and adults can be instructed in its use. The Flutter is a pipe-shaped device with a steel ball nesting loosely inside the covered bowl. A perforated cap over the bowl keeps the ball from falling out but allows exhaled air to escape. The exhaled breath pushes the ball up in the bowl, air briefly escapes, and the ball falls back down again. When the ball falls back, more pressure is exerted against the patient’s airway. The airway pressure generated during the exhalation varies from 5 to 35 cm H2O, depending on how fast the patient exhales. The rate at which the ball flutters up and down ranges between 2 and 32 Hz (Hertz or cycles/sec) and varies with the angle of the bowl. The high-frequency oscillations of backpressure on the airway caused by the fluttering steel ball are believed to help dislodge viscous secretions. Through trial and error the patient varies the expiratory flow rate and angle of the bowl to find the best oscillation rate to mobilize secretions.

The Acapella (Figure 10-19) is available in two expiratory flow models that allow the practitioner to better match the patient’s needs with the equipment. A third model, the Choice, can be disassembled for easy cleaning in the home or hospital. All models allow the user to adjust the frequency and amplitude of the oscillations. When the best expiratory flow, frequency, and amplitude of oscillations is found, the patient’s secretions will be optimally mobilized. See Box 10-9 for the steps in the procedure.

b. Coordinate the sequence of bronchial hygiene therapies: postural drainage, percussion, vibration, and positive expiratory pressure (ELE code: IIIF2f2) [ELE difficulty: R, Ap, An]

Coordinate OPEP therapy with effective maximal cough or “huff” cough techniques, CPT, or aerosolized medication delivery. As listed in Box 10-9, OPEP breaths should be alternated with directed coughing to clear secretions. Huff coughs are not full, deep coughs; rather, they are performed as follows:

c. Terminate the treatment if the patient has an adverse reaction to it (Code: IIIF1) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

During the treatment, ask the patient if he or she feels dyspnea, pain, or chest discomfort. Also monitor the patient’s breath sounds, blood pressure, heart rate, and breathing pattern and rate. Monitor oxygenation by pulse oximetry, mental clarity, and skin color. Be prepared to stop the treatment if necessary. Review the contraindications listed in Box 10-6 and hazards listed in Box 10-7.

d. Manipulate vibratory-type PEP therapy equipment by order or protocol (ELE code: IIA14c) [ELE difficulty: R, Ap, An]

1. Get the necessary equipment for the procedure

The Flutter (Figure 10-18) is a pipe-shaped device with a steel ball nesting loosely inside the bowl. The Flutter valve has been used with cystic fibrosis patients to help them loosen their secretions. It is believed that the highfrequency oscillations of backpressure on the airway caused by the fluttering steel ball help to dislodge thick (viscous) secretions. The Flutter valve must be kept upright during the patient’s exhalation to work properly.

The Acapella devices (Figure 10-19) use an adjustable counterweighted lever and magnet to produce variable frequency and amplitude of the expiratory pressure. They have the same clinical indications as the Flutter device. The original Acapella is available with a choice of two models based on the patient’s expiratory flow. The green DH model is indicated for patients with an expiratory flow >15 L/min (>0.25 L/sec). The blue MD model is indicated for patients with an expiratory flow <15 L/min (<0.25 L/sec). This allows for a better match of the unit with the patient’s pulmonary function. The newer Choice model can be disassembled for easier cleaning. A possible advantage of the Acapella devices over the Flutter devices is that they can be used in any patient position.

3. Troubleshoot any problems with the equipment

The patient must keep the Flutter in the proper position with the perforated cap in the upright position. This keeps the patient’s exhaled air blowing through the device to push up the steel ball. If a patient should cough secretions into the unit, it will become clogged. Air will not flow through it. Try clearing the obstruction from the mouthpiece with a cotton swab or by running warm water through the unit. If necessary, the cap can be unscrewed from the bowl and the steel ball and cup can be removed. Wash out any secretions and reassemble.

MODULE C

2. Modify high-frequency chest wall oscillation equipment by order or protocol (WRE code: IIA14b) [WRE difficulty: R, Ap]

a. Get the necessary equipment for the procedure

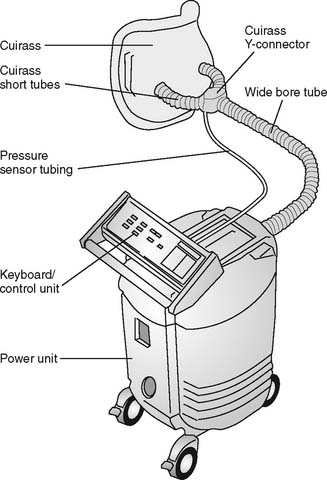

Currently, two HFCWO devices are available. The Vest (Figure 10-20) consists of a nonstretchable inflatable vest that covers the entire torso, an electrically powered pumping and control system, and two connecting hoses. The controls allow an adjustable air pulse rate of either 5 Hz (producing a vest pressure of 25 mm Hg) or 25 Hz (producing a vest pressure of 40 mm Hg).

The Hayek oscillator (Figure 10-21) consists of a flexible chest cuirass, an electrically powered pumping and control panel, and a connecting hose. This machine can deliver both positive and negative pressure to the patient’s chest throughout the breathing cycle. Added negative pressure around the patient’s chest will increase inspiration. Added positive pressure around the patient’s chest will increase expiration. The therapist can adjust an oscillation rate of 8 to 999 oscillations/min, with an I:E ratio of 6 : 1 to 1 : 6, and inspiratory and expiratory pressures of up to +70 cm water.

b. Put the equipment together and make sure that it works properly

Follow the manufacturer’s guidelines to assemble the components, as shown in Figures 10-19 and 10-20.

MODULE D

1. Analyze the available information to determine the patient’s pathophysiologic state (Code: IIIH1) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

2. Determine the appropriateness of the prescribed therapy and goals for the identified pathophysiologic state (Code: IIIH3) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

a. Review the planned therapy to establish the therapeutic plan (Code: IIIH2a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

b. Recommend changes in the therapeutic plan when indicated (Code: IIIH4) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

For any of the previously discussed procedures, be prepared to measure the patient’s blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate before, during, and after a change in therapy. Minor changes (less than 20%) can be expected. The patient’s oxygenation should improve as secretions and mucous plugs are removed and atelectatic areas open. The patient’s breath sounds should be auscultated before and after any treatment procedure. Listen for air moving into formerly silent areas and for secretions being cleared.

3. Record and interpret the patient’s breath sounds (Code: IIIA1b3) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

The patient’s breath sounds should improve if retained secretions are expectorated.

4. Record and interpret the type of cough the patient has and the nature of the sputum (Code: IIIA1b3) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

5. Recommend discontinuing the treatments based on the patient’s response to therapy (Code: IIIG1i) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

Review the previous discussion for indications that the patient has recovered and no longer needs bronchopulmonary hygiene procedures. For example, the secretions have decreased or can be easily expectorated by the patient, or both. Review Boxes 10-2 and 10-3 for contraindications and hazards/complications of postural drainage and percussion and vibration. Review Boxes 10-6 and 10-7 for contraindications and hazards/complications of PEP therapy.

American Association for Respiratory Care. Clinical practice guideline: postural drainage therapy. Respir Care. 1991;36:1418.

American Association for Respiratory Care. Clinical practice guideline: use of positive airway pressure adjuncts to bronchial hygiene therapy. Respir Care. 1993;38(5):516.

American Association for Respiratory Care. Clinical practice guideline: directed cough. Respir Care. 1993;38(5):495.

Branson RD, Hess DR, Chatburn RL. Respiratory care equipment, ed 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

Cairo JM. Lung expansion devices. In Cairo JM, Pilbeam SP, editors: Mosby’s respiratory care equipment, ed 8, St Louis: Mosby, 2009.

Campbell TC, Ferguson N, McKinlay RGC. The use of a simple self-administered method of positive expiratory pressure (PEP) in chest physiotherapy after abdominal surgery. Physiotherapy. 1986;72(10):498.

Eid N, Buchheit J, Neuling M, et al. Chest physiotherapy in review. Respir Care. 1991;36(4):270.

Eubanks DH, Bone RC. Comprehensive respiratory care, ed 2. St Louis: Mosby, 1990.

Fink JB. Volume expansion therapy. In Burton GC, Hodgkin JE, Ward JJ, editors: Respiratory care: a guide to clinical practice, ed 4, Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997.

Fink JB. Bronchial hygiene therapy and lung expansion. In: Fink JB, Hunt GE, editors. Clinical practice in respiratory care. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1999.

Fink JB, Hess DR. Secretion clearance techniques. In: Hess DR, MacIntyre NR, Mishoe SC, et al, editors. Respiratory care principals and practice. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2002.

Frownfelter DL. Chest physical therapy and airway care. In Barnes TA, editor: Core textbook of respiratory care practice, ed 2, St Louis: Mosby, 1994.

Hess DR, Branson RD. Chest physiotherapy, incentive spirometry, intermittent positive-pressure breathing, secretion clearance, and inspiratory muscle training. In Branson RD, Hess DR, Chatburn RL, editors: Respiratory care equipment, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

Hill KV. Bronchial hygiene therapy. In Aloan CA, Hill TV, editors: Respiratory care of the newborn and child, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997.

Hoffman GL, Cohen NH. Positive expiratory pressure therapy. NBRC Horizons. 1993;19(2):1.

Johnson NT, Pierson DJ. The spectrum of pulmonary atelectasis: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and therapy. Respir Care. 1986;31(11):1107.

Kacmarek RM, Dimas S, Mack CW. The essentials of respiratory care, ed 4. St Louis: Mosby, 2005.

Malmeister MJ, Fink JB, Hoffman GL. Positive-expiratorypressure mask therapy: theoretical and practical considerations and a review of the literature. Respir Care. 1991;36(11):1218.

Myslinski MJ, Scanlan CL. Bronchial hygiene therapy. In Wilkins RL, Stoller JK, Kacmarek RM, editors: Egan’s fundamentals of respiratory care, ed 9, St Louis: Mosby, 2009.

Myers TR. Positive expiratory pressure and oscillatory positive expiratory pressure therapies. Respir Care. 2007;52(10):1308.

Oberwaldner PT, Evans JC, Zach MS. Forced expirations against a variable resistance: a new chest physiotherapy method in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1986;2(6):358.

Rutkowski JA. Pulmonary hygiene and chest physical therapy. In: Wyka KA, Mathews PJ, Clark WF, editors. Foundations of respiratory care. Albany, NY: Delmar, 2002.

Scott AA, Koff PB. Airway care and chest physiotherapy. In Koff PB, Eitzman D, Neu J, editors: Neonatal and pediatric respiratory care, ed 2, St Louis: Mosby, 1993.

Shapiro BA, Kacmarek RM, Cane RD, et al, editors. Clinical application of respiratory care, ed 4, St Louis: Mosby, 1991.

Sobush DC, Hilling L, Southorn PA. Bronchial hygiene therapy. In Burton GC, Hodgkin JE, Ward JJ, editors: Respiratory care: a guide to clinical practice, ed 4, Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997.

van der Schans CP. Conventional chest physical therapy for obstructive lung disease. Respir Care. 2007;52(9):1198.

White GC. Equipment theory for respiratory care, ed 4. Albany, NY: Thomson Delmar Learning, 2005.

Wilkins RL, Stoller JK, Kacmarek RM, editors. Egan’s fundamentals of respiratory care, ed 9, St Louis: Mosby, 2009.

Wojciechowski WV. Incentive spirometers, secretion evacuation devices, and inspiratory muscle training devices. In Barnes TA, editor: Core textbook of respiratory care practice, ed 2, St Louis: Mosby, 1994.

SELF-STUDY QUESTIONS FOR THE ENTRY LEVEL EXAM See page 592 for answers

SELF-STUDY QUESTIONS FOR THE WRITTEN REGISTRY EXAM See page 616 for answers