Bronchiectasis

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

• Describe the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with bronchiectasis, including the following:

• Varicose (fusiform) form of bronchiectasis

• Cylindrical (tubular) form of bronchiectasis

• Cystic (saccular) form of bronchiectasis

• Differentiate between the following possible types of bronchiectasis:

• Describe the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with bronchiectasis.

• Describe the general management of bronchiectasis.

• Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAPs presented in the case study.

• Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve.

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

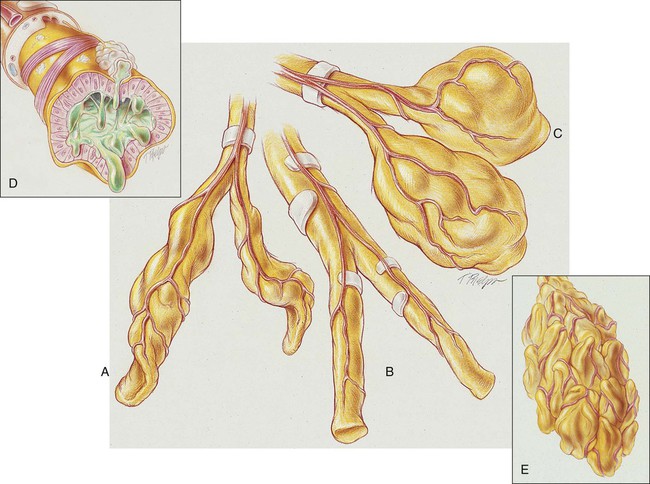

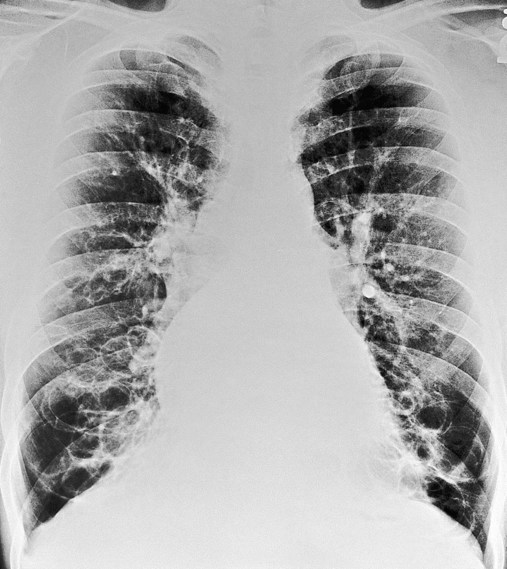

Cylindrical Bronchiectasis (Tubular Bronchiectasis)

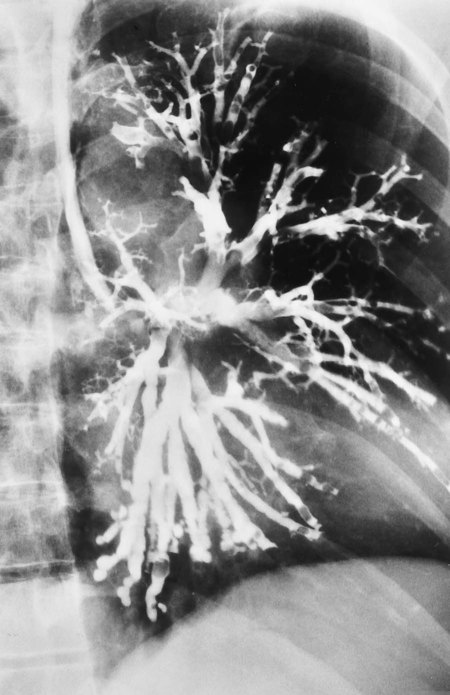

In cylindrical (tubular) bronchiectasis, the bronchi are dilated and rigid and have regular outlines similar to a tube. X-ray examination shows that the dilated bronchi fail to taper for 6 to 10 generations and then appear to end abruptly because of mucous obstruction (see Figure 13-1, B).

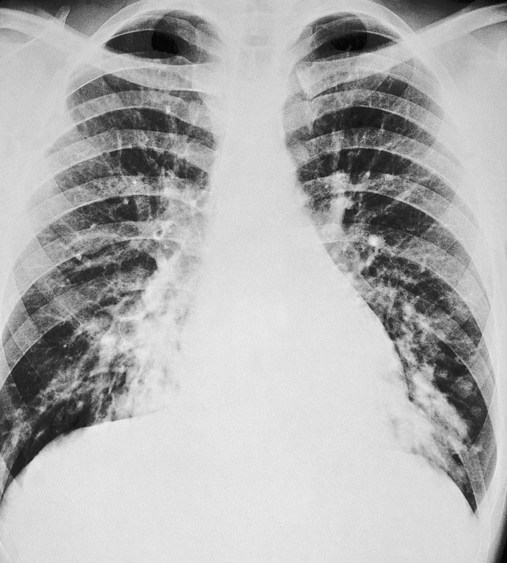

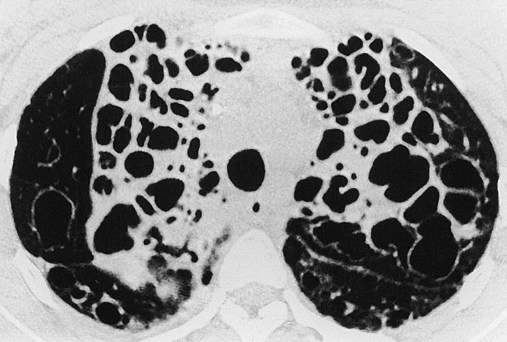

Cystic Bronchiectasis (Saccular Bronchiectasis)

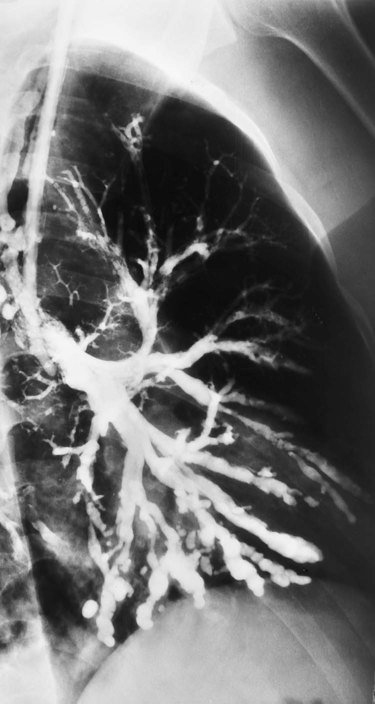

In cystic (saccular) bronchiectasis, the bronchi progressively increase in diameter until they end in large, cystlike sacs in the lung parenchyma. This form of bronchiectasis causes the greatest damage to the tracheobronchial tree. The bronchial walls become composed of fibrous tissue alone—cartilage, elastic tissue, and smooth muscle are all absent (see Figure 13-1, C).

The following are the major pathologic or structural changes associated with bronchiectasis:

General Management of Bronchiectasis

Respiratory Care Treatment Protocols

Oxygen Therapy Protocol

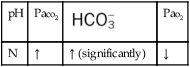

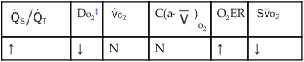

Oxygen therapy is used to treat hypoxemia, decrease the work of breathing, and decrease myocardial work. The hypoxemia that develops in bronchiectasis is usually caused by the pulmonary shunting associated with the disorder. When the patient demonstrates chronic ventilatory failure during the advanced stages of bronchiectasis, caution must be taken not to overoxygenate the patient (see Oxygen Therapy Protocol, Protocol 9-1).

Mechanical Ventilation Protocol

Mechanical ventilation may be necessary to provide and support alveolar gas exchange and eventually return the patient to spontaneous breathing. Because acute ventilatory failure superimposed on chronic ventilatory failure is often seen in patients with severe bronchiectasis, continuous mechanical ventilation is justified when the acute ventilatory failure is thought to be reversible—for example, when acute pneumonia exists as a complicating factor (see Mechanical Ventilation Protocols, Protocol 9-5, Protocol 9-6, and Protocol 9-7).

Medications Commonly Prescribed by the Physician

Expectorants

Expectorants sometimes are ordered when oral liquids and aerosol therapy alone are not sufficient to facilitate expectoration (see Appendix II, Expectorants). Their clinical effectiveness is doubtful.

CASE STUDY

Bronchiectasis

Admitting History and Physical Examination

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S Productive cough, hemoptysis, worse in past 5 months. Mild dyspnea on exertion.

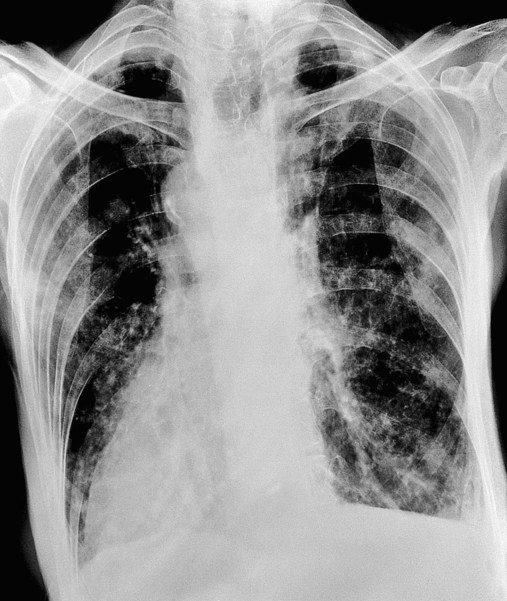

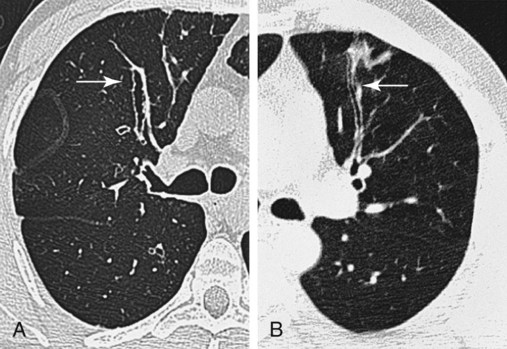

O Vital signs: normal. Afebrile. Observed moderate amount of mucopurulent, blood-streaked sputum. Crackles and rhonchi over RLL. Sputum culture: H. influenzae. CT scan suggests saccular dilation of RLL bronchi.

• Postpneumonic bronchiectasis RLL (history and CT scan)

• Excessive airway secretions and sputum production (rhonchi and sputum expectoration)

• Acute bronchial infection and hemoptysis (yellow, blood-streaked sputum)

P Oxygen Therapy Protocol (O2 via 2 L/min nasal cannula). Aerosolized Medication and Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Protocols (med neb 2.0 cc 20% acetylcysteine with albuterol 0.5 cc, followed by CPT and PD, q6h).

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S Cough, pleuritic left-sided chest pain, chills, fever, leg swelling. Has not been doing CPT and PD on regular basis. 30 lb weight gain. Smoking.

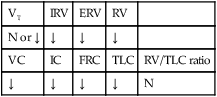

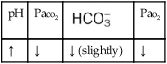

O HR 110; RR 20; BP 160/100; T 101.5° F; Spo2 (room air, rest) 86%, falls to 78% with mild exertion. Sputum thick, yellow-green, foul-smelling. Rhonchi and crackles both bases. Strong cough. Clubbing of digits. WBC 23,500 (80% neutrophils, 10% bands). Room air ABG; pH 7.51; Paco2 28 mm Hg;  21; Pao2 45 mm Hg.

21; Pao2 45 mm Hg.

• Bronchiectasis (old chart record)

• Excessive airway secretions (thick sputum, rhonchi)

• Infection likely (fever, yellow-green sputum); good ability to mobilize secretions (strong cough)

• Acute alveolar hyperventilation with moderate hypoxemia (ABG)

• Postural drainage therapy and smoking cessation noncompliance (history)

P Review CXR. Oxygen Therapy Protocol (2 L/min per nasal cannula). Aerosolized Medication Protocol and Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Protocols (med. neb. 2.0 cc 20% acetylcysteine with albuterol 0.5 cc, followed by CPT and PD q4h). Obtain sputum culture. Check I&O. Repeat ABG in am. Review deep breathe and cough, flutter valve, and pulmonary rehabilitation strategies with patient and his wife. Offer smoking cessation and weight reduction programs.

Discussion

The main challenge facing the respiratory care practitioner caring for the patient with bronchiectasis is one of efficient removal of excessive bronchopulmonary secretions. Over the years, postural drainage and percussion, good systemic hydration, and judicious use of antibiotics have been the hallmarks of therapy. More recently, intermittent use of mucolytics, percussive ventilation, and Lung Expansion Therapy (see Protocol 9-3) has become more common. Pneumococcal prophylaxis is, of course, important, as is prompt attention to parenchymal pulmonary infections such as pneumonia. The clinical distinction between chronic bronchiectasis and cystic fibrosis is a subtle one at the bedside, and the latter condition must always be ruled out in patients with bronchiectasis. The goal of long-term therapy in bronchiectasis is prevention of lung parenchyma–destroying pulmonary infections and avoidance of frequent hospitalizations. Hemoptysis is often a sign of more deep-seated infection requiring antibiotic therapy.

Digital clubbing associated with hypoxemia is another clinical manifestation of bronchiectasis. After the first assessment, both the Oxygen Therapy Protocol and Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol were administered appropriately (see Protocols 9-1 and 9-2). The therapist’s review of the chest x-ray allowed him to target the postural drainage therapy. Low-flow oxygen per nasal cannula, aerosolized bronchodilators (albuterol) and mucolytic medication (acetylcysteine), chest percussion, and postural drainage therapy were selected from these protocols and applied with good results.

)

)

)O2, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;

)O2, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;  , pulmonary shunt fraction;

, pulmonary shunt fraction;  , mixed venous oxygen saturation;

, mixed venous oxygen saturation;  , oxygen consumption.

, oxygen consumption.

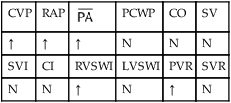

, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricular stroke work index; SV, stroke volume; SVI, stroke volume index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricular stroke work index; SV, stroke volume; SVI, stroke volume index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

21, and Pa

21, and Pa ratios, venous admixture, and hypoxemia. These pathophysiologic mechanisms caused clinical manifestations of an increase in blood pressure and heart rate, acute alveolar hyperventilation with moderate hypoxemia, and rhonchi.

ratios, venous admixture, and hypoxemia. These pathophysiologic mechanisms caused clinical manifestations of an increase in blood pressure and heart rate, acute alveolar hyperventilation with moderate hypoxemia, and rhonchi.