Chapter 7 Breast Reduction

There is no other procedure in breast surgery where the surgeon has a greater opportunity to demonstrate his or her aesthetic abilities than with a breast reduction. In these cases, there is an excess of skin, fat and parenchyma usually coupled with an overall breast shape that is usually less than aesthetic. With careful surgical manipulation of the volume of the breast along with intelligent incision planning, a beautiful and long-lasting breast shape can be created that complements the reduction in breast volume.

Preoperative Evaluation

Chief Complaint

There are many factors that merit specific attention when assessing a patient for a potential breast reduction. The most basic of these relates to the patient’s physical complaints related to her large breasts. It is important to document each patient’s specific complaints, which can include, but are not limited to, neck and back pain, headaches, shoulder grooving with painful indentations in the skin secondary to support garments, submammary intertrigo and paresthesias in the hands and fingers. More often than not, there is a general discomfort about the upper torso related to years of excess weight dragging down from the shoulders. One useful maneuver used to assess the effect of the weight of the breast on the upper torso is to gently lift each breast upwards with the examining hand while standing in front of the patient (Figure 7.1). By taking the weight of each breast off the chest wall, many patients will observe an immediate relief of symptoms. It should be stressed in each patient consultation that the purpose of undergoing a breast reduction is to relieve these upper torso complaints. Such a discussion, properly documented in the patient’s chart, has practical as well as medicolegal implications as some patients become so focused on the aesthetic appearance of the breast postoperatively that this basic fact is at times forgotten amidst discussions related to scarring or breast shape.

Reproductive History

Childbearing can have a tremendous impact on the size and shape of the breast. To have a better historical understanding of the stresses that have been placed on the breast and the associated supporting soft tissue framework, it is helpful to document the number of children a patient has had, whether or not she breast-fed and how long it has been since she stopped. Also, the maximum size that developed either as a result of pregnancy alone, or during the breast-feeding process itself, can be helpful in understanding how dramatically the skin envelope was stretched. This information may explain why the breast has a certain appearance and, as well, allow the surgeon to predict, at least to some extent, how the skin envelope will react to surgical manipulation. Whether or not a patient wishes to attempt to breast-feed in the future should also be noted and discussed preoperatively. It is generally permissible to allow patients who wish to breast-feed after breast reduction to make the attempt. If the breast ducts are still in continuity with the nipple, it is entirely possible that a breast reduction will not appreciably interfere with the ability to breast-feed. Of course, this is by no means a guarantee and these issues must be discussed preoperatively to help head off any misconceptions on the part of the patient.

Past Medical History

It is helpful to make special note of any history related to inflammatory bowel disease. In particular, a past history of ulcerative colitis has been associated with the development of pyoderma gangrenosum, a condition characterized by a progressively enlarging and painful ulcer located at an incision line. Initially, the ulcer is small and is associated with a clear drainage that leads to a benign presumptive diagnosis of a ‘stitch abscess’ or premature erosion of an absorbable suture through to the surface of the skin. Generally, the ulcer enlarges despite the institution of oral antibiotic therapy. Eventually, the ulcer becomes painful in a manner that seems out of proportion to the appearance of the wound and the wound edges develop an irregular undermined purplish border (Figure 7.2). Biopsy reveals an inflammatory infiltrate and the process is rapidly reversed with a tapered course of oral steroids. Recognizing any previous history of diagnosed ulcerative colitis or even colitis-like symptoms can lead to a heightened index of suspicion and early diagnosis should this condition develop.

Surgical Timing

There are three general time periods in a woman’s life where macromastia can develop to the point where upper torso symptoms begin to develop and surgery can become indicated. Macromastia can first present in adolescent girls in association with general pubertal development. Anywhere from the age of 12 up to 18 years of age, breast growth over and beyond what would be considered proportionate to the remainder of the body habitus can occur. This early phase of breast over-development presents challenges that are unique in the treatment of macromastia. Not only can there be the usual upper torso symptoms found in other types of macromastia, but other issues related to the emotional well-being of the patient during this very volatile and important part of a young woman’s life must also be considered. As breast volume increases, it is not uncommon for patients to become extremely self-conscious, often to a point of withdrawing socially. As a result, important social skills can either be delayed in developing or fail to develop altogether. Also, from a simple anatomic standpoint, it can be difficult for such young patients with macromastia to participate in sports or other athletic activities without the size of the breasts being a hindrance. For all of these reasons, it is completely acceptable to consider surgical correction of macromastia even as a young teenager. What must be balanced against the decision to perform surgery early is the potential for breast development to be incomplete with further growth postoperatively necessitating a re-reduction later on. For this reason, each case must be assessed individually to arrive at the best solution for the patient. If breast over-development is modest, it is reasonable to wait until the age of 16–18 in the hope that breast size will have stabilized toward the end of pubertal development. However, if at any time, even in patients as young as 14, breast over-development begins to interfere with what the family or the patient sees as normal social development, it is completely reasonable to proceed with a breast reduction, accepting the fact that another touch up reduction may well be required at a later date when breast development has completely stabilized.

Lastly, and usually somewhat later in life, many women will present with macromastia associated with weight gain as it is very common for the breast to increase significantly in size as the overall weight of the patient increases. In some patients, even only a modest increase in weight can result in a disproportionate increase in the size of the breast. In others, a weight gain that pushes the body habitus of the patient into the obese to morbidly obese category is required to affect significantly the size of the breast. No matter what the circumstance, in order to provide a stable result, it is best to delay surgery until the patient’s weight remains somewhat constant over a defined period of time. It is reasonable to delay surgery until there is a weight fluctuation of no more than 10 pounds (4.5 kg) over a time span of 6 months to 1 year to ensure that an unexpected change in the weight of the patient will not adversely influence the postoperative size and shape of the breast. Certainly, a further increase in the weight of the patient could create a recurrence of symptoms, but a much more common concern on the part of patients is related to what will happen to the breast should the patient lose weight. It can be very difficult to predict how the volume of the breast will change in association with a generalized weight loss and the exact relationship between breast size and overall body weight can be quite variable. What can be stated for certainty is that breast size will change in association with an overall reduction in body fat. In patients where breast volume has historically has been sensitive to the overall weight of the patient, the change in breast size that occurs can be significant. In other patients, there may be only a negligible change in the size of the breast. No matter what the circumstance, it is best to caution the patient that any change in body fat content can subsequently have an effect on not only the size but the shape of the breast as well (Figure 7.3).

Effect on Breast-feeding

Another common concern, particularly for younger patients who are of childbearing age, is the effect that breast reduction surgery has on the ability to breast-feed. The answer to this question is somewhat dependent on the technique employed to perform the procedure with the critical determinant being whether or not the substance of the gland has been divided from, and no longer communicates with, the nipple. Therefore, in patients who have undergone a free nipple grafting technique, there is little hope of maintaining breast-feeding potential as the direct ductal communication between the nipple and the gland has been severed. While it is remotely possible that an ‘inosculatory’ regrowth of the ductal remnants in the nipple and the gland could occur, allowing these structures to variably reconnect, the likelihood of this occurring to any functional degree is low. Alternatively, in the inferior pedicle technique, the main central substance of the gland remains connected to the nipple, which, theoretically, should preserve the ability to breast-feed. Other pedicled techniques such as the vertical breast reduction technique follow a similar logic. Therefore, if a superior pedicle or a superomedial pedicle is constructed so as to maintain a communication between the nipple and a large enough retained glandular segment, breast-feeding potential should be maintained. Of course, there are many other variables involved in successful breast-feeding that have nothing to do with the surgical alteration of the breast and many women who wish to breast-feed cannot for a host of different reasons. As a general rule, approximately two-thirds of women who wish to breast-feed are able to do so and this ratio is not changed by breast reduction surgery that maintains a direct nipple to gland communication.

Examination

Observations

Breast base width

Many patients, particularly those with significant macromastia associated with varying levels of obesity, present with a very wide breast base diameter that extends in a diffuse fashion onto the lateral chest wall. In many cases, the base diameter of the breast is not only wide but asymmetric as well (Figure 7.4). Making note of this aspect of breast shape can direct appropriate attention to managing each breast in a slightly different fashion using a preoperative plan that narrows the wider breast to a greater degree than the opposite narrower breast. Also, liposuction recontouring of the lateral chest wall fullness can be used to recreate proportion between this area and the reduced breast. It is advisable to discuss the need for lateral liposuction ahead of time with the patient as this aspect of the procedure can lead to additional swelling and ecchymosis over and above that seen with a standard breast reduction procedure.

Upper pole contour

The contour of the upper pole of the breast is assessed for any degree of concavity. Should there be a lack of fullness in the upper pole, direct surgical recontouring with internal suture suspension will be required to provide the optimal result and this must be factored into the overall surgical plan (Figure 7.5).

Lower pole skin texture

In patients with severe macromastia, the weight of the breast along with the expansion of the skin envelope can be so severe that ischemic changes can be noted in the most dependent portion of the breast. Often these changes can be seen as a dull rubor present in the skin along with the presence of a dilated capillary network (Figure 7.6). Such changes are indicative of a reduced capacity for these tissues to tolerate surgical manipulation and serve as a marker for increased risk of wound healing difficulties and possible NAC ischemia. Making note of these changes can allow the surgeon to alter the technique of reduction as needed and also allow adequate preoperative counseling to be done to appraise the patient of her risk for complications.

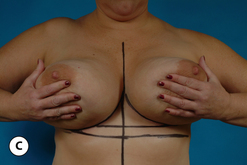

Asymmetry

Finally, any asymmetry in the size and shape of the breasts, the level of the inframammary fold (IMF) and the position of the NAC are noted. To assess these relationships it is helpful to stand several feet away from the patient as she stands comfortably upright and observe the overall appearance of the breasts. At times it requires a careful and considered side to side comparison, but often subtle differences in the volume or shape of the breasts can be identified. When asymmetries are noted, they often come as a complete surprise to the patient and it can sometimes be helpful to have the patient stand in front of a mirror to confirm these asymmetries. Once identified, each asymmetry can then be discussed as to how it will be treated. It is at this point that a very important part of the preoperative consult takes place. Generally, patients will seek reassurance that any difference in the size or shape of the breasts will be corrected. It is helpful to communicate to the patient that every effort will be made to create the most symmetrical result possible and the overwhelming likelihood is that whatever asymmetries are present will be improved. However, it is very common for small asymmetries in size, shape or position to persist even after the breast reduction has fully healed. By proactively discussing the issue of breast asymmetry, patients become better educated as to the challenges that breast reduction can pose with regard to the quality of the final result and are better able to accept and understand any small asymmetries that may persist postoperatively. Using this approach can be a tremendous aid in helping to head off any patient misconceptions about breast reduction and can help to maintain a very high level of patient satisfaction.

Breast Measurements

After a general overview of the size, shape and symmetrical relationship of the breasts is completed, documentation of several key measurements is performed. First, the length from either the midclavicle or the sternal notch to the nipple is measured (Figure 7.7). This provides information regarding the length of the breast. In many instances of significant macromastia, this measurement will be in excess of 30 cm. The usefulness of this measurement is somewhat limited, however, in patients undergoing a breast reduction using an inferior pedicle technique as it does not have a direct bearing on the length of the pedicle that will ultimately provide vascular inflow to the NAC. Patients with an excessive clavicle to NAC distance may simply have a breast that is positioned low on the chest wall. For this reason, a second measurement is performed documenting the distance in the midline of the breast from the inframammary fold up to the nipple (Figure 7.8). When using an inferior pedicle technique, this measurement provides a direct measure of the length of the pedicle that will be providing vascular inflow to the NAC. As a general guideline, for patients who measure 15 cm or less, necrosis of any portion of the NAC or underlying fat or parenchyma is unusual and an inferior pedicle technique can be used with confidence. For pedicle lengths of 15–20 cm, the risk for vascular compromise increases but does not preclude the safe use of an inferior pedicle technique. For lengths of greater than 20 cm, greater care in the creation and management of the pedicle is strongly advised so as to avoid ischemic complications. Of course, numerous other factors enter into the usefulness of the length of the pedicle as a predictor for potential complications including obesity, volume of reduction, medical illness and a smoking history. It is possible to use inferior pedicles in excess of 30 cm in length without any hint of vascular compromise (Figure 7.9). Therefore, despite the lack of direct correlation between the length of the pedicle and the potential for ischemic complications, it is still a worthwhile effort to document this measurement as it can serve as a guide to assist the surgeon in predicting when ischemic complications might become more likely. Lastly, measuring the dimensions of the areola (in cases where the areola is asymmetric) can document the presence of an excessively large areolar diameter. This then triggers discussion of the fact that the areolar diameter will be made smaller. Rarely is this an issue for patients and special requests for an inordinately large or small postoperative areolar diameter can be factored into the surgical plan. As with the subject of asymmetry, it is far better to have these types of discussions ahead of time rather than trying to recover after the fact with the uncomfortable task of having to deal with a dissatisfied patient postoperatively.

Operative Technique

Overall Strategy

By using this strategy for describing and evaluating a breast reduction technique, it is possible to organize a surgical approach better and develop a understanding of how all the components of a breast reduction procedure fit together to create a successful more complete outcome. To this end, several different combinations of techniques that satisfy these requirements can be recognized as specific methods of breast reduction. Although minor variations on these themes exist, there are basically four distinct procedures that are used to perform breast reduction. These include liposuction breast reduction, vertical breast reduction, short scar periareolar inferior pedicle (SPAIR) breast reduction and inverted T breast reduction with or without a free nipple and areola graft. Each of these procedures will be described in detail.

Liposuction Breast Reduction

Operative strategy overview

While recent developments in breast reduction technique have focused on reducing the extent of cutaneous scarring, perhaps no other strategy is more effective at accomplishing this than liposuction breast reduction (LBR). Although some have referred to LBR as ‘no scar’ breast reduction, it is perhaps more accurate simply to recognize that whatever small scars are created are generally so inconsequential as to be of no significance at all. In this method, standard liposuction technique is applied to the breast through strategically placed stab incisions to allow sufficient reduction in breast volume to be performed. These scars can be hidden in the inframammary fold, around the areolar junction with the breast and in the axilla. Using two entry portals allows for crosshatching to be performed and more effectively allows for the removal of greater amounts of breast volume than one portal alone. Several reports have documented the utility of this technique in safely reducing the breast in a fashion that does not interfere with the subsequent ability of the breast to be appropriately screened with mammography. In difficult cases, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation can be used to visualize dense areas. What becomes an issue in LBR is the ability to remove appropriate amounts of tissue in dense breasts as well as managing the redundant skin envelope once the volume is reduced. Certainly, in the aged breast, when the bulk of the breast volume is made up of fat, a significant volume reduction can be accomplished with relative ease. In the more youthful fibrous breast, volume reduction can be somewhat limited using standard liposuction technique. In these cases, it may be more helpful to use alternative techniques such as ultrasound assisted liposuction (UAL) or power assisted liposuction (PAL) to extract the fat from within the interstices of the breast parenchyma more effectively. Once the desired volume reduction is performed, a relative excess of skin is created. In young patients with a more elastic skin quality, a mild rebound contraction takes place with modest amounts of fat removal and acceptable results can be obtained without the need for any type of skin tightening procedure (Figure 7.10). In older patients, this effect is less dramatic and an excessive and ptotic skin envelope can result after volume reduction that exacerbates the ptotic appearance of the breast. While some surgeons have simply accepted this unavoidable and variably unaesthetic ptotic breast shape, others have applied skin envelope reduction techniques in an attempt to improve the aesthetic result. In all instances, however, the simplicity and speed with which the procedure can be performed makes it an attractive technique in appropriately selected patients. Using the technique analysis described previously, LBR involves basically the use of a central mound to maintain the vascularity of the NAC, removes tissue in a diffuse fashion from each segment of the breast, either accepts skin redundancy or uses a standard skin excism pattern to take up the excess skin and shape the breast.

Operative technique

After appropriate volume reduction has been performed, the redundant skin envelope is addressed. There is no need to perform any deep dissection within the breast to remove additional volume, therefore removal of the redundant skin envelope is simply a superficial procedure. The redundant skin is removed according to the previously made marks, limiting the resection to no deeper than the dermis. Additional tailoring can be performed as needed to recontour the breast into the most aesthetic shape possible. The incisions are then simply closed without the need for any drains (Figures 7.11, 7.12).

Postoperatively, a support garment is worn simply for comfort for a period of 4–6 weeks or until the swelling has largely resolved. Wound care proceeds as for any surgical incision. Any exposed suture ends are clipped at 7–10 days and the incision is treated with a vitamin E-based scar cream for a period of 6 weeks. Decisions regarding return to work are made individually depending on the nature of the patient’s occupation. Many patients can return to light duty in as little as 3–5 days; however, I allow up to 6 weeks off for occupations involving heavier manual labor. Recreational aerobic or weight lifting activities are restricted for 4 weeks from the time of surgery.

Vertical Breast Reduction

Parenchyma

With the creation of a superior or superomedial pedicle, the tissue in the inferior pole of the breast becomes expendable and it is this tissue that is removed to accomplish the breast reduction. Typically, removal of tissue can be feathered around the pedicle to allow additional amounts of parenchyma to be removed as needed. This is a technical maneuver that must be performed with great care as over-resection of tissue in this area can create a divot-like deformity in the inferior pole of the breast. At times, this resulting cleft is seen only when the patient raises her arms and puts the lower pole of the breast under a relative stretch and, occasionally, it can be seen even as a static deformity with the arms at the sides (Figure 7.13). This potential complication is made even more troublesome by the fact that it is very hard to predict when this complication will occur as traditional vertical technique has advocated that the inferior pole of the breast be made to appear markedly flattened and even distorted to a certain extent at the end of the procedure. Therefore, the shape that will result in the inferior pole of the breast once full settling has taken place can be a source of uncertainty. This aspect of the vertical mammaplasty creates a significant conceptual problem. Vertical mammaplasty enthusiasts believe that removing this inferior pole tissue will prevent the breast from developing the well-known complication of ‘bottoming out’ with loss of an aesthetic lower pole contour. What remains underemphasized is that the surrounding breast parenchyma that is expected to fall into the lower pole void also stretches and, in a sense, bottoms out. If the attachments of Scarpa’s fascia in the lower pole of the breast are likewise resected with the parenchyma, the propensity of the remaining lower pole tissues to ‘bottom out’ into the subscarpal space is further aggravated. This phenomenon was recognized early on thus leading to the realization that if the lower pole contour was not overcorrected initially, an overly ptotic and elongated lower pole with an inordinately high NAC position could result. In effect, the eventual shape of the breast that results after vertical mammaplasty actually depends on a certain and undefined component of bottoming out. Therefore, the technical challenge of removing just enough tissue from the lower pole of the breast to allow the surrounding parenchyma to fall into the void and, at the same time, predicting how much the breast would settle seems to be a relatively unpredictable task, leaving the quality of the final result perhaps more to chance than might be optimal. Also, these uncertainties become more significant as the amount of breast tissue removed increases.

Skin

The original description of the vertical mammaplasty advocated creating a periareolar opening that had the exact circumference as the incision in the areola. In this way, the two incisions would match perfectly, creating a well-healed and inconspicuous scar. This strategy, however, created an incision length from the bottom of the periareolar pattern down to the inframammary fold that could reach alarming lengths in larger reductions. The length of this ‘vertical’ incision could be reduced somewhat by stopping the inferior extent of the incision short of the IMF by several centimeters and then adding an additional component of plication after the breast had been reduced. This maneuver tended to prevent the vertical scar from extending down onto the abdomen. Also, the placement of an accordion type suture pulled up to gather the incision was advocated as a means of shortening the distance between the IMF and the bottom of the areola. Despite these maneuvers, one of the hallmark complications of a less than ideal result after a vertical mammaplasty is a bottomed out, ptotic appearing breast where the distance from the IMF to the bottom of the areola is far too long and out of proportion to the overall shape of the breast. In essence, since the length of the periareolar and areolar incisions are nearly equal, any redundancy in the skin pattern must be taken up by the vertical segment alone. In larger breast reductions, this can result in a pronounced excess of bunched skin at the bottom of the vertical segment near the IMF. Several strategies for managing this bunched skin have been advocated, including the use of purse string sutures, debulking with liposuction, as well as just simply allowing the area to heal and contract in over time. Despite these surgical maneuvers, the end result of this skin excess problem is often a contracted, irregular and atrophic scar that distorts the lower pole of the breast. It is most often visible when the arms are raised over the head but, in severe instances, can be seen as a static deformity with the arms at the sides. With this in mind, it is telling that secondary revision of this lower pole deformity accounts for many of the revisionary procedures that have been reported after traditional vertical mammaplasty. To avoid these types of complications, it is far better to distribute the stress of managing the redundant skin envelope over the entire incision length. This is accomplished by diagramming a periareolar lift type pattern drawn in a manner very similar to a patient undergoing a circumvertical mastopexy where the outer periareolar incision has a larger diameter than the inner areolar incision. By using a purse string suture to control the larger periareolar opening, the dimensions of the vertical incision can be diminished, which places less overall stress on the vertical component. Secondly, there is no significant drawback to curving the inferior portion of the incision out laterally near the IMF to help take up the remaining vertical component of excess skin. This curvilinear skin takeout allows skin to be removed along two vectors both horizontally and vertically, a maneuver that affords great latitude in taking out any redundant skin and negates any potential for the vertical scar to extend down onto the chest wall as can happen with a straight vertical skin takeout. For vertical mammaplasty ‘purists’, these modifications run against the traditional teaching of precisely equal periareolar closures and a vertical component that runs straight down to the IMF without medial or lateral deviation. However, once these modifications become part of the overall plan, the advantages of the vertical, or more precisely the circumvertical mammaplasty, become evident.

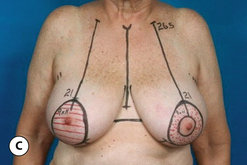

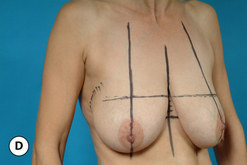

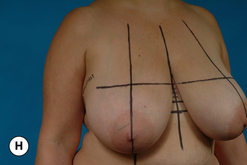

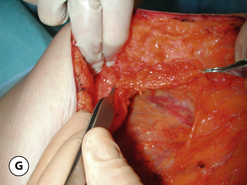

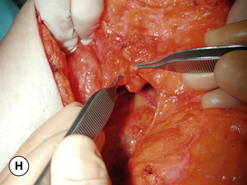

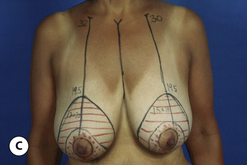

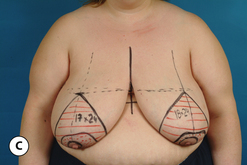

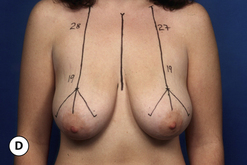

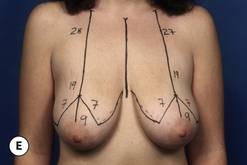

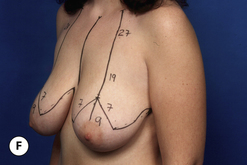

Marks

The marks for this modified vertical mammaplasty are straightforward and easy to apply. With the patient standing upright and the shoulders held in a tension free posture, a line joining the two inframammary fold locations is marked across the torso so that it can be seen in the midline area between the breasts (Figure 7.14 C). If the inframammary folds are asymmetric, the higher fold line is used as the reference line. The breast meridian is then diagrammed on each side in such a way so as to divide the breast vertically into two equal halves (Figure 7.14 D). Measuring up from the inframammary fold reference line in the midline, an additional line is marked extending superiorly in 1 cm increments. At the 4 cm mark, a second line is drawn parallel to the inframammary fold reference line and this line extends across the tops of the breasts such that it intersects the breast meridian on each side. This then becomes the superior extent of the proposed periareolar incision (Figure 7.14 E). By then transposing the breast superomedially and superolaterally, the breast meridian can be ‘ghosted’ onto the breast to identify the medial and lateral extent of the periareolar pattern (Figure 7.14 F,G). The margins of the proposed vertical extension of the pattern are then marked. By lifting the top of the areola up to the desired level on the breast, the inferior pole of the breast can be pinched together until a pleasing shape has been created. The approximate location of this vertical takeout is then estimated and marked with the line extending down to the inframammary fold (Figure 7.14 H,I). When the distance from the IMF to the nipple exceeds 10 cm, it is best to begin to draw the inferior vertical segment with a slight lateral curve as it extends inferiorly toward the IMF. This will prevent the vertical incision from becoming too long and will help shape the breast appropriately. A smooth line is then drawn just below the inferior margin of the areola and the medial, superior and lateral points are joined into a smooth and slightly elongated oval (Figure 7.14 J,K). Since the management of the periareolar opening is similar to that which occurs in an augmentation mastopexy, it is possible to use the interlocking Gore-Tex technique to assist in managing the periareolar closure. These marks are applied as desired by marking the eight cardinal points around the areola as well as around the periareolar incision (Figure 7.14 L). Symmetrically applying the marks from side to side completes the marking pattern (Figure 7.14 M,N).

Operative technique

At the time of surgery, the areola is placed under maximal tension with the aid of a breast tourniquet and an areolar diameter of 40–44 mm is marked with the aid of a multidiameter areolar marker (Figure 7.15 A,B). The areolar and periareolar incisions are then made and the intervening tissue de-epithelialized (Figure 7.15 C). The dermis is divided around the periphery of the periareolar opening leaving a small 5 mm dermal cuff that will ultimately hold the Gore-Tex purse string suture. This dermal cuff is undermined directly at the level of the dermis for a distance of 1–2 cm back from the incisional edge. This eventually will allow the periareolar opening to be closed without inordinate bunching or tissue crowding (Figure 7.15 D). The proposed vertical skin incisions are then made and the intervening segment of breast tissue removed (Figure 7.15 E–G). Trimming either medially or laterally can be performed as needed to reduce the breast further. If needed, the parenchymal removal can extend medially and laterally around the inferior half of the areola. Every effort should be made to keep the attachments of Scarpa’s fascia to the underside of the breast intact. At no time should the amount of tissue that is removed be so extensive that a void is created in the inferior pole of the breast. If desired, the breast can now be undermined in the subglandular plane to allow the underside of the breast to be advanced superiorly. This undermining is limited to the central breast area and every effort is made to keep the internal mammary perforators intact (Figure 7.15 H,I). By advancing the deep surface of the breast superiorly and suturing it to the pectoralis major fascia with a 3-0 absorbable monofilament, any preoperative concavity that may have been present in the upper pole of the breast can be corrected. One to three such sutures can be used as needed to shape the upper pole (Figure 7.15 J). Once the desired amount of tissue has been removed, the vertical pillars are closed again with a 3-0 absorbable monofilament suture (Figure 7.15 K,L) and the skin incision is closed in a tailor tack fashion with staples until a pleasing shape is created (Figure 7.15 M,N). If necessary, the inferior extent of the plication can curve outward along the IMF as needed to create a pleasing aesthetic shape to the lower pole. By insetting the NAC into the periareolar defect again with staples and sitting the patient up, the shape of the breast can be assessed. Further plication, tissue removal or elevation of the NAC can be performed as needed to create the desired result. Once the optimal size and shape have been created, the stapled edges are marked with a surgical marker and the staples removed (Figure 7.15 O,P). The redundant skin is de-epithelialized (Figure 7.15 Q) and the vertical segment closed. A drain may be placed as desired. The NAC is then inset using the interlocking Gore-Tex technique (Figure 7.15 R–T). At this point the breast should have a pleasing shape. Slight fullness in the upper pole and a mild flattening along the vertical segment are acceptable but should not be so excessive as to detract from the aesthetic appearance of the breast (Figure 7.15 U–X). Dressings consist of Dermabond tissue glue to the incision which is then covered with Opsite dressings. A surgical bra is applied. Postoperatively, suture ends are clipped at 7–10 days and a vitamin E-based scar cream is applied for 6 weeks. Non-strenuous activities are allowed almost immediately; however, vigorous exertion is delayed for 4 weeks. Full healing has generally taken place by 6 months, at which time the final shape of the breast can be reliably assessed (Figures 7.16 A,B, 7.17 A–H).

SPAIR Mammaplasty

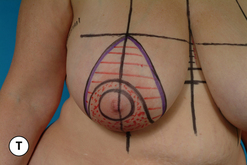

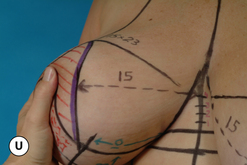

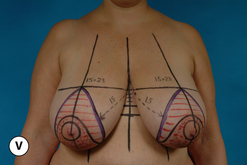

Marks

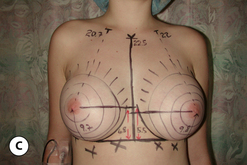

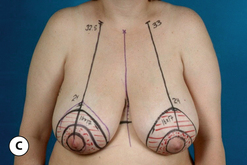

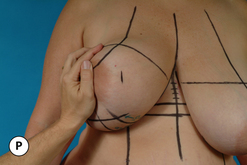

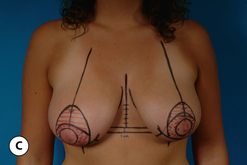

The marking pattern for the SPAIR procedure is best applied with the patient standing upright, weight evenly distributed on both feet and the shoulders and arms held in a tension free and loose posture at the sides (Figure 7.18 A,B). The goal of the marking pattern is to identify the dimensions of the skin envelope that will need to be preserved to easily wrap around the inferior pedicle that will be used to carry the NAC. To this end, this operation typifies exactly the old axiom that it is not what is taken that is important, but rather it is what is left behind that will most directly affect the final result. Initially, the midline over the sternum is marked along with the location of the inframammary fold on each side. The most inferior extent of the inframammary fold for each breast is identified and a line connecting these two points is carried across the midline. If the two folds are at different levels, these two lines will not intersect and further marks are based on the higher of the two folds. This line drawn across the torso allows the location of the fold to be identified visually without the need to manipulate the breast in any way (Figure 7.18 C,D). Laterally, the inframammary fold line is extended over and around the lateral margin of the breast to mark the limits of the dissection of the lateral flap (Figure 7.18 E). In the midline, a distance of 4 cm is measured up from the inframammary fold line (Figure 7.18 F) and a second line parallel to the inframammary fold line is drawn across the top of each breast (Figure 7.18 G). This line marks the top of the periareolar pattern. The breast meridian is then marked on each side by visually dividing the breast in half and drawing a line that bisects the breast extending from the upper chest down and around the breast and onto the chest wall (Figure 7.18 H,I). When drawing the breast meridian it is best to ignore the position of the nipple as many patients present with a nipple position that is either laterally or more commonly medially translocated and basing the location of the breast meridian on such a translocated nipple would cause the remainder of the marking pattern to be applied asymmetrically. Once the top of the pattern is identified, the inferior portion is then marked. By lifting the inferior pole of the breast away from the abdomen, an 8 cm wide pedicle can be measured centered on the breast meridian (Figure 7.18 J). This measurement is repeated along the breast meridian as it extends up onto the breast and in this fashion a perfectly oriented 8 cm wide inferior pedicle is drawn directly in the midline of the breast (Figure 7.18 K,L). On either side of the pedicle, a distance of 8–10 cm is measured up from the inframammary fold (Figure 7.18 M,N) and these two points are joined in a line that parallels the line of the inframammary fold (Figure 7.18 O). As an approximation, in smaller breast reductions of 500 grams or less per side, the 8 cm measurement is used and in larger reductions of more than 1000 grams per side, this length measures 10 cm. For reductions between 500 and 1000 grams per side this length measures 9 cm. The goal of these marks is to identify a skin envelope in the lower pole of the breast of sufficient surface area easily to cover the lower portion of the breast after it is reassembled. To this end, there is no advantage to shortening this measurement to 7 cm and only in cases of gigantomastia where 1500 grams per side or more are planned to be removed can the measurement be lengthened up to 12 cm. Finally then, the amount of skin that will be preserved medially and laterally is determined. By gently rotating the breast up and out until a smooth and rounded contour is created in the medial portion of the breast, the breast meridian can be translocated onto the medial breast skin at the level of the nipple (Figure 7.18 P). This mark then determines how much skin must be left medially to wrap easily around the reduced breast. The process is then reversed as the breast is rotated up and in and a mark is made on the lateral portion of the breast that will similarly identify how much lateral skin to preserve (Figure 7.18 Q). In this fashion, four cardinal landmarks are identified that define the dimensions of the periareolar portion of the pattern (Figure 7.18 R). The lateral, superior and medial marks are then smoothly joined to the inferior pedicle marks to determine the limits of the periareolar pattern (Figure 7.18 S). After the periareolar pattern is finalized, the proposed limits of the inferior pedicle are outlined by carrying the 8 cm pedicle marks up and around the NAC, skirting the proposed areolar incision by a distance of 2–3 cm (Figure 7.18 T). As a final check to the marking pattern, the distance from the midsternal line to the most medial edge of the periareolar mark should measure at least 12 cm (Figure 7.18 U). If this is not the case, the markings should be rechecked to be certain the breast was not unintentionally pulled too far laterally as the medial mark was made. Lastly, the dimensions of the periareolar pattern are measured at their widest horizontal and vertical extent. This measurement is helpful in that it is an indication of how challenging the procedure will be, particularly as it relates to managing the skin envelope. In an approximate fashion, any measurement less than 15 cm indicates that the procedure should proceed easily and skin redraping will not be a challenge. For measurements of between 15 and 20 cm, it can be anticipated that intraoperative adjustment of the proposed vertical segment may well be required to obtain the best result. And for measurements greater than 20 cm, experience with the technique will be required to manage the redundant skin envelope effectively. It is highly recommended that the marking pattern be photographed and photos of the marks be made available in the operating room at the time of surgery. This visual information can be of help in confirming intraoperative observations that are sometimes made during the procedure relative to asymmetries in breast volume or, in particular, differences in breast width. Also, these photos can be referenced later after full healing has taken place and the final result has stabilized. Going back and assessing how the marking pattern impacted upon the final result can be an enlightening educational tool (Figure 7.18 V,W).

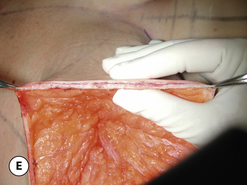

Operative technique – initial dissection

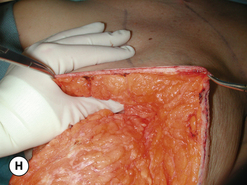

The procedure is performed under general anesthesia and, while most patients are able to be discharged home the same day, occasionally a patient will elect to stay overnight in the hospital either for pain control issues or to help manage postoperative nausea and vomiting. At surgery, the patient is placed in a mild beach chair position to help bring the base of the breast up level with the plane of the floor. This helps the surgeon better judge how the tissue planes fit together during the dissection. The periareolar tissues as well as the proposed vertical segment are infiltrated with a diluted solution of 1% lidocaine with epinephrine to assist with hemostasis (Figure 7.19 A). A breast tourniquet is applied and the areola is placed under maximal stretch while an areolar diameter of 40–44 mm is marked with the aid of a multidiameter areolar marker. The areolar and periareolar incisions are made and the skin over the inferior pedicle is de-epithelialized as is a small segment of skin immediately adjacent to the periareolar incision (Figure 7.19 B). The dermis is then divided around the entire periphery of the periareolar defect leaving a cuff of dermis attached to the periareolar skin incision that measures 5 mm in width (Figure 7.19 C,D). This dermal cuff will serve as the architectural scaffold into which the Gore-Tex purse string suture will eventually be placed. The dermis of the inferior pedicle is left intact to preserve whatever potential dermal contribution is present to the vascularity of the NAC. Once the dermal shelf has been created along the margins of the periareolar incision, the dermal edges are undermined and the flaps are dissected away from the main substance of the breast mound. Flap dissection proceeds in an exacting fashion by initially dissecting the flaps directly at the level of the dermis and then progressively increasing the thickness of the medial (Figure 7.19 E,F) and superior (Figure 7.19 G,H) flaps until the chest wall is reached. At this point the thickness of the medial and superior breast flaps approaches 4–6 cm. Every effort must be made to make these dissection planes as smooth and evenly contoured as possible. Laterally, the flap is dissected down to the lateral mark directly at the junction of the superficial fat with the breast capsule (Figure 7.19 I). This creates a lateral flap that is only 1–2 cm thick in most patients; however, experience has shown that the lateral flap must be this thin or the breast will demonstrate too much lateral fullness and a ‘boxy’ appearance to the breast will result. At the junction of the relatively thinner lateral flap with the thicker superior flap in the upper outer quadrant of the breast, every effort must be made to make this transition smooth and without an abrupt step off. This will help ensure a smooth rounded contour to the breast in this area. The reasoning behind this flap dissection strategy is that the initial flap dissection must be thin to allow the skin edges to be eventually pulled in by the purse string suture without creating tissue crowding as the flap edges are drawn around the inferior pedicle. Deeply, however, the medial and superior flaps are left thicker to provide substance and a smooth and contoured shape to the reduced breast. It is important to emphasize that the dissection along the medial and lateral aspects of the pedicle along the inframammary fold must stop slightly above the fold to avoid opening the loose subscarpal space. In this manner, the position of the inframammary fold will remain unchanged as a result of the procedure and a stable breast shape will be better maintained over time.

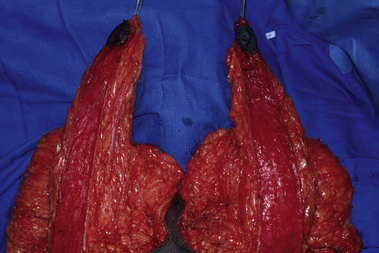

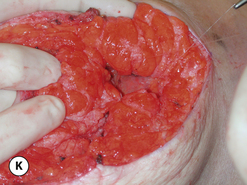

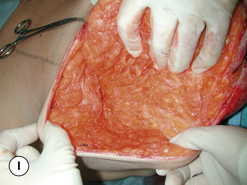

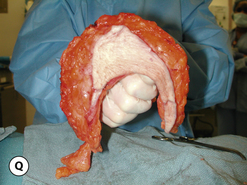

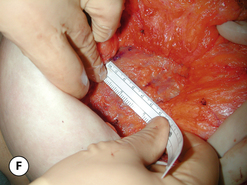

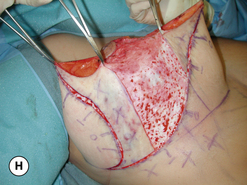

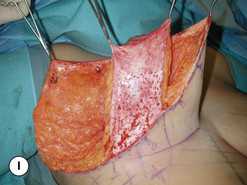

Once the flaps have been developed, the main substance of the breast mound can be delivered from within the confines of the flaps (see Figure 7.19 J,K). The redundant parenchyma is then dissected free from around the pedicle, working from medial to lateral. During this dissection, the internal breast septum is protected by, working from deep to superficial, to better isolate the redundant tissue in the superior aspect of the breast mound (see Figure 7.19 L). This allows the pedicle to be skeletonized with little risk of inadvertent injury to the septum and the associated vascular arcade supplying the NAC. Every effort is made not to undermine the pedicle and a full and evenly contoured pedicle of parenchyma is retained to provide vascularity to the NAC as well as provide the basis for the eventual shape of the breast (see Figure 7.19 M–P). Once the pedicle has been completely skeletonized, it should fit evenly into the space created by the flap dissection without any excess fullness or, conversely, any areas that are in any way underfilled. The shape of the excised segment of parenchyma is that of a horseshoe with the lateral limb being slightly longer than the medial limb (see Figure 7.19 Q). Trimming can be done in any area where the dissection planes seem uneven or excessively full. Once the breast has been completely reduced, the weight of the resected specimen is recorded for comparison to the preoperative estimates as well as for comparison to the amount eventually resected from the opposite breast. Such comparisons can be particularly helpful in cases of breast asymmetry.

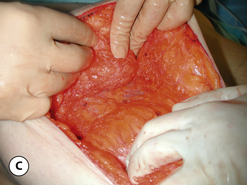

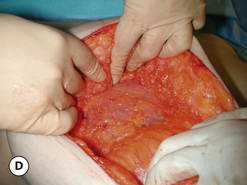

Operative technique – breast shaping

After the major portion of the breast reduction has been accomplished, the breast must then be reassembled into a pleasing aesthetic shape. In many patients, simply as a result of the preoperative planning of the procedure and the manner in which the surrounding flaps and pedicle have been sculpted, all that is required at this point is a tailor tack recontouring of the lower pole skin envelope to create an aesthetic shape. However, in patients who present with any degree of concavity in the upper pole of the breast, internal breast shaping maneuvers can be used to good effect to improve the overall quality of the final result. To prepare the breast flaps for internal suture plication, first the medial and superior flaps are undermined to release them from their attachments to the pectoralis major muscle and allow repositioning. The medial flap is undermined for a distance of 1–3 cm with care being taken not to inadvertently injure the very important internal mammary perforators. The superior flap is undermined up to and beyond the superior border of the breast (Figure 7.20 A,B). The deep leading edge of the undermined superior flap is then advanced upward to shift the position of the entire flap superiorly, where it is sutured to the pectoralis major fascia to hold it in position. One to three evenly spaced sutures are used to secure the flap in the desired location. In essence this amounts to an ‘autoaugmentation’ of the superior pole of the breast. The degree to which the flap is advanced superiorly is determined individually for each patient. Mildly ptotic patients will require only a modest flap advancement while extremely ptotic patients will require a more aggressive degree of undermining and a more significant flap advancement to correct the upper pole concavity (Figure 7.20 C–F). Medially, the undermined leading edge of the flap is imbricated upon itself to gather the deep flap tissues together and create a more rounded and full medial contour to the breast (Figure 7.20 G–J). Finally, the base of the inferior pedicle is sutured down to the pectoralis fascia to hold the pedicle in position and keep it from falling off laterally in the breast (Figure 7.20 K). The net effect of these shaping maneuvers is to improve the three-dimensional relationship between the flaps and the pedicle with the goal being a full and rounded breast contour that is properly positioned on the chest wall.

Operative technique – skin envelope management

After the breast has been reduced and the shaping maneuvers applied as needed, the redundant skin envelope in the inferior pole of the breast must be managed. The exact dimensions of the skin resection are determined using a ‘tailor tack’ approach with skin staples. By securing a hemostat to the pedicle and applying upward traction, the redundant skin flaps on either side of the pedicle will buckle. These two buckle points are stapled together to begin the plication of the inferior pole. This staple point is called the key staple as it sets the rest of the plication pattern (Figure 7.21 A–C). The remainder of the redundant skin envelope is then folded in on itself and progressively stapled into position until a smooth and contoured shape has been created (Figure 7.21 D,E). As the staple line is developed from superior to inferior, the pattern curves inferolaterally along the inframammary fold as much as needed to create an aesthetic shape. At no time should the staple line extend down onto the upper abdomen. It is this lateral curving of the plication line that prevents many of the wound healing problems seen at the base of the vertical incision in the more classic vertical mammaplasty techniques. Alternatively, a small ‘T’ can be added at this point to take up the redundant tissue. The critical goal of this plication maneuver is to take up the redundant skin envelope and create an aesthetic breast shape immediately. This represents one of the great advantages of the SPAIR technique, namely that the breast must have an aesthetic appearance at the time of the procedure. Not only is this an advantage for the patient, but the surgeon can now make much more accurate and technically correct judgments about breast size and shape due to the fact that the breast has an aesthetic shape immediately as compared to the classic vertical mammaplasty where the distorted early breast appearance can hinder such efforts. To this end then, after the vertical segment has been plicated, the NAC is inset into the periareolar defect with staples and the patient is placed upright to assess the shape of the breast. Adjustment of the staple line can be performed as needed by either tightening a bit more the line of plication or, alternatively, loosening some of the staples to create the desired shape. Once the desired breast shape has been achieved, the patient is returned to the supine position and the plication line is marked with a surgical marker. Cross-hatched orientation marks are placed across the plication line to aid in accurately putting the vertical incision back together once the appropriate skin segments have been either de-epithelialized or resected (Figure 7.21 F). After the staples have been removed, the dimensions of the plicated inferior skin envelope can be visualized. The shape of the resection area typically assumes that of a canted ‘V’ with the inferior point of the ‘V’ angled laterally along the inframammary fold (Figure 7.21 G). The inferior pedicle is then de-epithelialized to preserve any potential contribution the subdermal vascular plexus may be providing to the blood supply to the NAC (Figure 7.21 H) and the redundant medial and lateral wedges of tissue on either side of the pedicle are removed (Figure 7.21 I). It is helpful in particular to remove the lateral wedge of tissue in a full thickness fashion as this then allows the lateral flap to pass over on top of the de-epithelialized inferior pedicle to meet the medial incision without creating any tissue crowding or bunching (Figure 7.21 J). A drain is placed as desired and the vertical incision is closed using 4-0 absorbable monofilament sutures placed in an inverted interrupted fashion followed by a subcuticular skin closure with the same material (Figure 7.21 K).

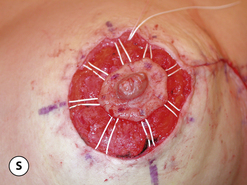

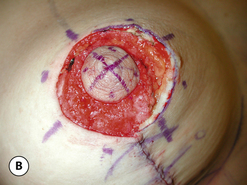

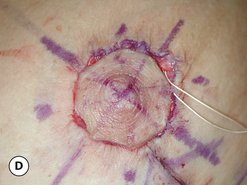

Operative technique – management of NAC

The final step in completing the procedure is management of the periareolar defect. Here all the technical details described previously for either the simple purse string or the interlocking Gore-Tex closure are utilized. If the dimensions of the periareolar defect are greater than 10 cm, the tendency is to use the simple purse string technique as use of the interlocking Gore-Tex technique can become cumbersome with periareolar defects larger than this. When the interlocking Gore-Tex technique is used, it is helpful to re-resect the periareolar opening to create a circular defect. Commonly, this will require resecting a small additional wedge of skin along the medial margin of the periareolar defect (Figure 7.22 A). Once the defect is re-excised, the eight cardinal points utilized in the interlocking Gore-Tex technique are applied (Figure 7.22 B) and the suture is placed in the dermal shelf developed at the beginning of the procedure, creating the characteristic pinwheel appearance (Figure 7.22 C). The purse string is then cinched down and the areola inset with a running 4-0 absorbable monofilament suture to complete the procedure (Figure 7.22 D–F). Postoperatively, suture ends are clipped at 7–10 days and a support garment is worn for comfort for 6 weeks. Full return to vigorous activity is allowed at 4 weeks (Figures 7.23–7.27).

Inverted T (Wise) Pattern Inferior Pedicle Breast Reduction

Operative strategy overview

For many surgeons, the gold standard technique for performing breast reduction remains the inverted T inferior pedicle technique. This technique bases the blood supply to the NAC on an inferior pedicle, resects tissue from around the periphery of the pedicle and uses a tapered wedge pattern to resect skin from around the inferior pole of the breast with a central superior extension that results in a scar along the inframammary fold with a central extension up to and around the NAC, hence the name the inverted T.

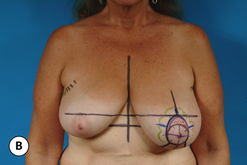

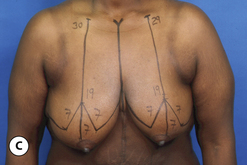

Marks

The patient is marked in the upright position. A line is drawn in the midline of the chest and a breast meridian is then drawn on each breast designed to separate the breast visually in half (Figure 7.28 A). The location of the inframammary fold is transposed onto the anterior surface of the breast by placing the fingers of the examining hand under the breast at the level of the fold and curling them forward so they can be palpated with the opposite hand (Figure 7.28 B). The distance from the clavicle to this point is then measured as an aid to applying the marks symmetrically (Figure 7.28 C). A 7 cm limb is then angled down medially and laterally from this point (Figure 7.28 D), creating a distance of between 7 and 10 cm between the bottom of these limbs. This distance determines how much the base diameter of the breast will be narrowed. A line is diagrammed in the inframammary fold and it is carried far enough medially and laterally to ensure that a dog ear will not form at the end of the incision after closure. The inferior ends of the vertical limbs are then joined to the inframammary line with an arcing sweep that preserves a small amount of skin centrally and resects more skin laterally. This minor adjustment can assist in maximizing breast projection and help in narrowing the breast base diameter (Figure 7.28 E, F).

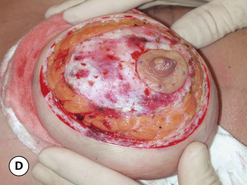

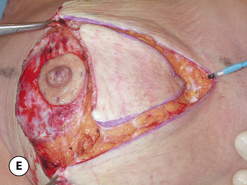

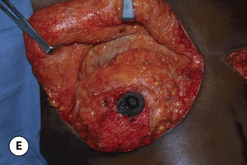

Operative technique

As with the other breast reduction techniques, an incision measuring 40–44 mm is made around the areola with the areola under maximal tension. The incisions are then made through the dermis and into the subcutaneous tissue around the entire periphery of the pattern. However, the base of the inferior pedicle is left undisturbed and the skin about the pedicle is simply de-epithelialized (Figure 7.29 A–C). The superiorly based flaps are then dissected free from the remainder of the breast mound using a similar dissection strategy to the SPAIR procedure. The goal is to sculpt the flaps such that they are somewhat thin to begin with and then become progressively thicker as dissection proceeds down to the chest wall. This will ensure that smooth rounded contours will be created once the flaps are closed around the inferior pedicle. The inferior pedicle is then skeletonized with care being taken not to undermine the pedicle and potentially interrupt the vessels in the breast septum. Also, dissection proceeds carefully in the region of the inframammary fold on either side of the pedicle to avoid opening up the loose subscarpal space, which could potentially lead to inferior migration of the breast parenchyma and the classic complication of ‘bottoming out’ (Figure 7.29 D,E). The flaps are then approximated along the inframammary fold and up along the vertical incision with interrupted and running 4-0 absorbable monofilament sutures. The patient is then placed in the upright position and a circular defect is created in the midline at the apex of the breast. The areola is then sutured into position to complete the procedure (Figure 7.29 F–H).

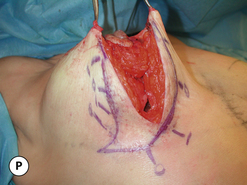

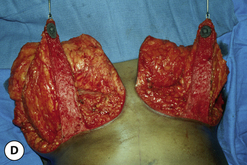

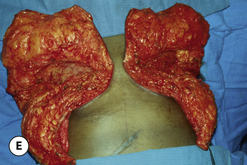

The advantages of the classic inferior pedicle inverted T breast reduction are that it is a very technically straightforward procedure, it is widely applicable to many patients and even very large breast reductions can be performed with relative ease (Figures 7.30–7.32). One nuance to this classic technique relates to the shaping of the breast. After the flaps and pedicle have been dissected free, it is possible to suture the pedicle to the pectoralis major fascia using absorbable shaping sutures to stabilize the shape of the breast during the early healing process. Utilization of such internal shaping sutures is just one of many maneuvers that have been reported over the years in an attempt to improve the results of breast reduction (Figure 7.33 A–I).

Another nuance to the classic inverted T inferior pedicle procedure involves the use of a free nipple graft. In selected cases, the length of the pedicle may be so excessive that it is deemed by the surgeon an unreasonable risk to attempt a pedicled procedure. In these cases, the NAC is removed as a full thickness graft, thinned slightly and temporarily placed in a saline moistened sponge. Then, after the breast is reassembled and the inframammary and vertical skin incisions are closed, the location for the NAC is determined with the patient upright and this area is de-epithelialized and the graft applied and secured with a bolus tie-over dressing. An alternative method is to attempt a pedicled procedure initially with conversion over to a full thickness graft technique only after it becomes clear that the pedicled NAC is ischemic. In this instance, the NAC is removed as a full thickness graft and the ischemic portion of the pedicle is debrided back to viable tissue. The flaps are closed and the NAC applied as a graft as before. The disadvantage of the full thickness graft technique relates to the certain loss of sensation that results as well as the potential for variable take of the NAC as a graft with loss of nipple projection. Also, in patients with darkly pigmented areolas, variable take of the graft can result in depigmentation of the areola. However, in properly selected patients, the technique can provide consistent and reliable results while obviating the possibility of NAC necrosis. It remains up to each individual surgeon to assess the risks versus the benefits when deciding when to use the free NAC graft technique.