Chapter 3 Breast problems

3.1 Introduction

History

Discovering a lump is the complaint of most concern in patients presenting with breast disease. The clinician must answer the questions: Is a discrete (dominant) lump really present? Then, if the answer is yes: Is it a carcinoma? Most carcinomas present as painless lumps. The other common forms of presentation of breast problems are painful breasts (often with general lumpiness), nipple discharge and skin changes.

Physical examination

The fully exposed breasts are examined initially in the seated and then the supine position.

On inspection any asymmetry or alteration in contour of the breasts is noted (Box 3.1). Most differences in size of the breasts are developmental. Accessory nipples may be observed along the milk line between axillae and groins. The most common site is just below the normal breast. Accessory breast tissue is most commonly seen between the true breast and the axilla and may increase in size initially with lactation but is rarely connected to the mammary ducts, although a rudimentary nipple may appear as a pore on the skin.

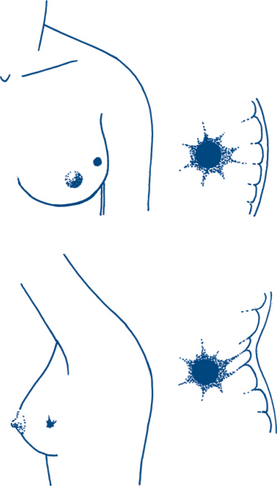

The patient, while sitting, is asked successively to raise the hands fully above the head, to clasp hands behind the neck, to place hands on hips, to press the hands against the hips and to lean forwards. Asymmetry and distortion by a mass or skin tethering (Fig 3.1) and retraction, are often only detected by movements such as arm elevation or leaning forward, or by tension of the underlying chest muscles. Dermal oedema due to lymphatic obstruction causes a skin appearance resembling orange peel or pig skin (peau d’orange). This sign is a feature of a locally advanced cancer or a local inflammatory lesion such as an abscess or may follow treatment for breast cancer, particularly when the axillary lymph nodes have been dissected and when the patient has received radiotherapy to the conserved breast. Erythematous discoloration of skin may be due to underlying infection, duct obstruction during lactation or, occasionally, inflammatory malignancy. In the areola the nodules of Montgomery’s follicles are seen. These can sometimes become infected. Bilateral nipple retraction may be a developmental anomaly. A recent history of unilateral nipple retraction suggests underlying breast disease, particularly malignancy or periductal inflammation.

Palpation is initially performed with the patient supine. A pillow is placed beneath the shoulder on the side being examined and the arm on that side is abducted with the hand placed behind the head (Fig 3.2). This spreads the breast over a larger area, reducing the depth of the breast tissue and thus facilitating palpation. The whole breast is palpated, including the axillary tail, using the palmar surfaces of the fingers with the hand flat. This avoids mistaking normal fat or glandular tissue for discrete lumps, a mistake that is common if the tips of the fingers are used. The detection of a discrete or dominant lump requires experience in palpating the normal texture of the breast and recognising the normal and cyclical variation. If a lump is discovered or the patient’s suspicion of a lump is confirmed, its physical characteristics are fully assessed. Many dominant lumps in the breast are cystic so that assessment for fluctuation is important; however, fluctuation will not be elicitable with deep cysts. The important physical characteristics of cancer are discreteness and induration. Fixity is usually a late sign except where a cancer is unusually superficial or in the infra-mammary fold of the breast.

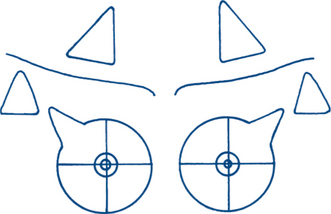

Finally the patient is brought back to the seated position to complete the examination. Any lumps are assessed by palpation with one hand, then by both hands compressing the breast between them. Fixation of the lump to the underlying muscle is tested by assessing for change in mobility upon contraction of the pectoralis major muscle. The patient is asked to press her hand against the hip in order to contract the muscle. The axilla is palpated while resting the patient’s forearm on the examiner’s forearm. Palpable nodes are common in the normal axilla; firm nodes of 1 cm or more suggest involvement by metastatic tumour. Enlarged and tender nodes may indicate an inflammatory or infective process. The examination is completed by looking for signs of metastatic disease, palpation for supraclavicular nodes and for hepatomegaly and bone tenderness, particularly in the spine, and auscultation of the chest. A diagramatic record can then be made of the findings (Fig 3.3).

Diagnostic tests

Imaging techniques: mammography, ultrasound

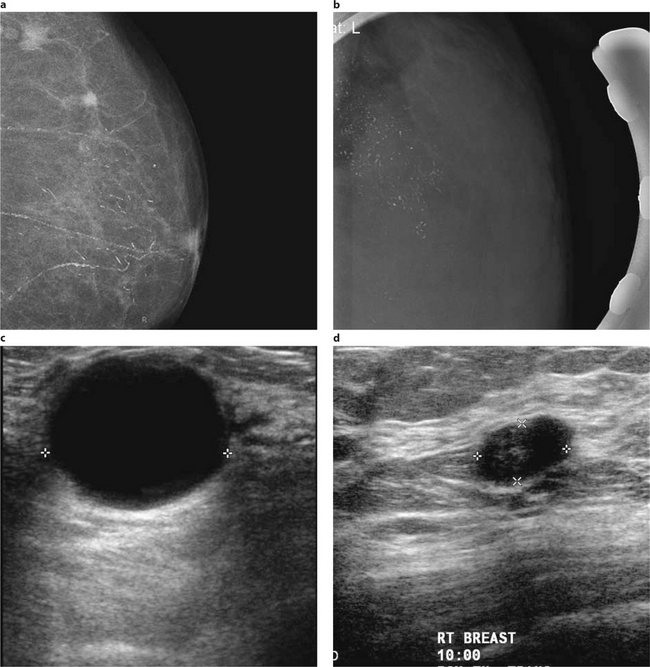

Positive signs of malignancy on mammography include an irregular infiltrating mass and focal pleomorphic microcalcification. Differentiation of mass lesions and calcified lesions uses a combination of mammographic workup including magnification, ultrasound and image-guided biopsy (Fig 3.4).

Figure 3.4 Mammographic and sonographic images of the breast

Courtesy of Dr Manish Jain, MIA

3.2 Breast pain

Breast pain (mastalgia) is a very common problem and is not often due to malignant disease.

Clinical features and diagnosis

On examination, tender lumpiness is felt in the breast, usually without a dominant lump. The association of a lump will require appropriate imaging and percutaneous cytological aspiration cytology or biopsy; management of the lump in such instances is the main problem. The diagnosis of pain can be established by regular review without recourse to radiological examination or biopsy. Patients are frequently reassured simply to have an explanation for their pain and may not require specific treatment. Appropriate diagnostic and screening tests should be undertaken on the basis of clinical signs and estimated risk of cancer (particularly age).

Treatment plan

Managing breast pain is often difficult. The principles of treatment are:

3.3 Breast lump

History and physical examination

1 Carcinoma

Examination is completed by assessing the areas of possible metastatic spread and staging the disease by clinical examination (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2

BREAST CANCER STAGING

| Primary tumour (T) | |

| T0 | No detectable primary tumour |

| Tis | In situ tumour (DCIS, LCIS, Paget’s disease of the nipple) |

| T1 | Tumour less than 2 cm |

| T2 | Tumour 2 cm and less than 5 cm |

| T3 | Tumour 5 cm and greater |

| T4 | Tumour directly involving skin or chest wall and inflammatory cancer |

| Regional lymph node involvement (N) | |

| N0 | No lymph node involvement |

| N1 | Mobile ipsilateral axillary nodes |

| N2 | Fixed or matted axillary nodes or internal mammary nodes |

| N3 | Infraclavicular or supraclavicular nodes |

| Metastatic involvement (M) | |

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1 | Any distant metastases |

3 Fibrocystic change (breast cyst)

Macrocystic change is a form of fibrocystic change where cyst formation is marked. Cysts often present as dominant lumps. Pain and tenderness are not common. A solitary cyst is smooth, spherical or domed, tense and firm. It may be possible to detect fluctuation. The clinical distinction is important because these lesions can be diagnosed and treated by aspiration at the initial consultation and the patient can be reassured. If aspiration does not provide complete resolution of the lump, if the aspirate is bloodstained, if the mass persists after aspiration or if there is early re-accumulation of fluid, biopsy is indicated.

Diagnostic plans

2 Mammography

Mammography is the only reliable widely available means of detecting breast cancer before a mass can be palpated in the breast. Experienced radiologists can interpret mammograms correctly in about 90% of cases.

3.4 Nipple discharge

The patient can usually describe the nature of the discharge or its appearance on the brassiere. Spontaneous bloodstained or serous nipple discharge is usually due to a duct papilloma. Brownish-green or creamy discharge, which can be expressed from multiple ducts and is often bilateral, is suggestive of duct ectasia. It is important to know whether the discharge is unilateral or bilateral, whether there may be a physiological discharge and whether the patient is able to locate the segment of breast from which pressure will produce the discharge.

Paget’s disease of the nipple is a rare cause of a minor degree of nipple discharge that may also be confused with eczema (Table 3.1). This condition is an areolar intra-epithelial carcinoma spreading from a deeper intraduct carcinoma.

Table 3.1 Differences between Paget’s disease and eczema of the nipple

| Paget’s disease | Eczema |

|---|---|

| Unilateral | Bilateral |

| Older patients | Younger |

| Not itchy | Itchy |

| No vesicles or pustules | Vesicles and pustules |

| Nipple destruction | Nipple normal with areolar changes |

| Palpable lump often present | No lump |

| Mammographic changes | Normal mammogram |

Diagnostic plans

Unilateral bloody discharge from a single duct

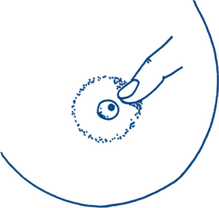

This is usually caused by an intraduct papilloma. Carcinoma is a rare cause and usually presents with an associated lump or mammographically identifiable lesion but is occasionally due to imaging occult ductal cancer in situ. With intraduct papilloma a mass is only occasionally palpable or visible sonographically. It is useful for the clinician to define, if possible, the involved duct by pressure on different segments of the breast around the nipple at the margin of the areola as this may facilitate focused imaging and surgery (Fig 3.5).

Diagnostic plan

In the majority of cases the clinical diagnosis is obvious. Cytology of the discharge is indicated, together with breast imaging. Fine needle aspiration cytology or core biopsy for histology of an associated mass may be required. Cytology in duct ectasia will show only inflammatory cells. Ductal epithelial cells or red blood cells suggest the presence of an intraduct papilloma. Rarely, atypical cells or malignant cells are seen with more serious intraduct pathology.

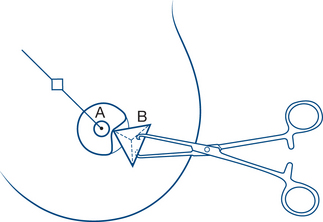

Treatment plan

With a bloodstained nipple discharge the segment of breast from which the discharge arises should be defined. At operation the responsible duct is probed and excised with an adequate margin (microdochectomy) through a circumareolar incision. Histology will almost always confirm a benign lesion (Fig 3.6).

3.5 Gynaecomastia

Clinical features

3 Carcinoma of the lung and other tumours

Other tumours, such as hepatoma, adrenal or testicular tumours, are rare causes of gynaecomastia. Carcinoma of the male breast should be considered in patients with unilateral gynaecomastia, but carcinoma is a rare cause of breast enlargement in men. The diagnosis of carcinoma is suggested by a hard painless lump, which is asymmetrical or eccentric in location and is associated with signs of fixation or a bloodstained nipple discharge. Axillary nodes may be enlarged.