17 Brainstem

General Arrangement of Cranial Nerve Nuclei

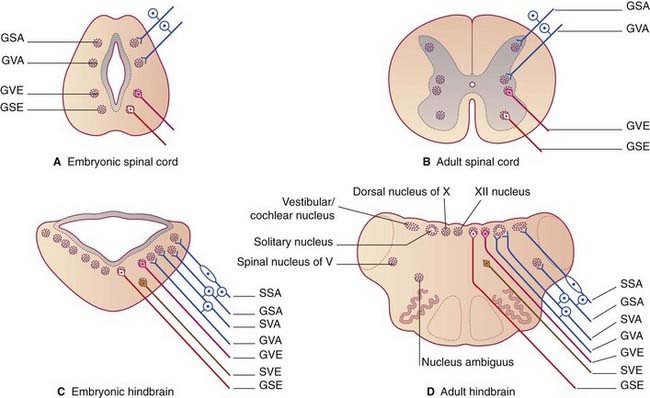

In the thoracic region of the developing spinal cord, four distinct cell columns can be identified in the gray matter on each side (Figure 17.1A, B). In the basal plate, the general somatic efferent column supplies the striated muscles of the trunk and limbs. The general visceral efferent column contains preganglionic neurons of the autonomic system. In the alar plate, the general visceral afferent column receives afferents from thoracic and abdominal organs. A general somatic afferent column receives afferents from the body wall.

Three additional cell columns (Figure 17.1C, D) serve branchial arch tissues and the inner ear, as follows.

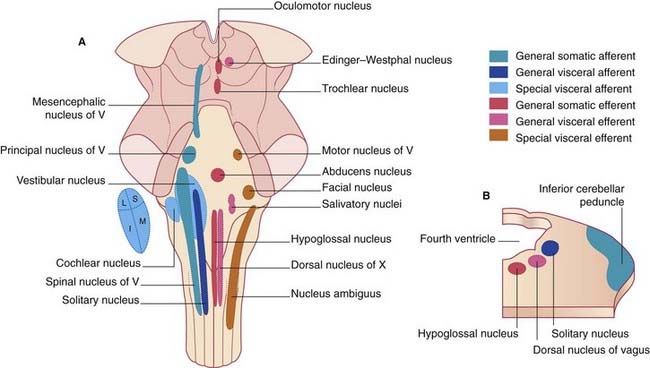

Figure 17.2 shows the position of the various nuclei in a dorsal view of the brainstem.

Background Information

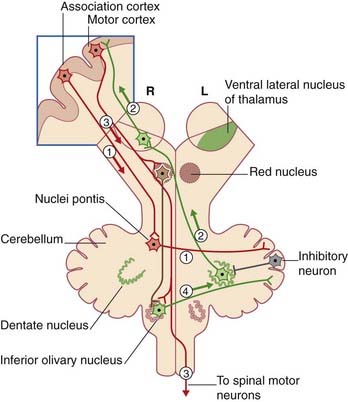

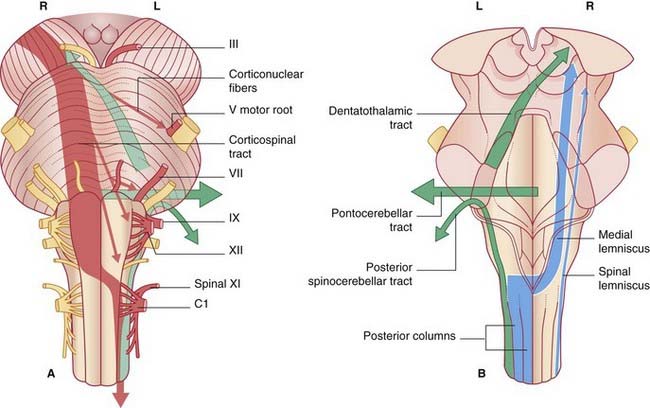

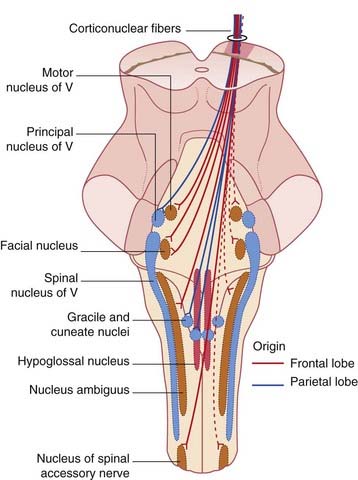

The same arrangement holds good for the brainstem. The pyramidal tract fibers terminating in the brainstem are corticonuclear. As shown in Figure 17.3, their distribution is predominantly contralateral to somatic and branchial motor nuclei, and entirely contralateral to the somatic sensory nuclei.

Figure 17.3 Posterior view of brainstem, showing distribution of corticonuclear fibers from the right cerebral cortex.

For a basic understanding of neural relationships in the brainstem, it is also essential to appreciate hemisphere linkages to the inferior olivary nucleus and to the cerebellum (Figure 17.4).

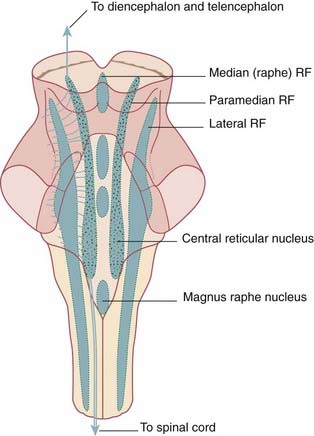

The general layout of the reticular formation (Figure 17.5) is borrowed from a figure in Chapter 24 devoted to this topic. It may be consulted when reading under this heading in successive descriptions.

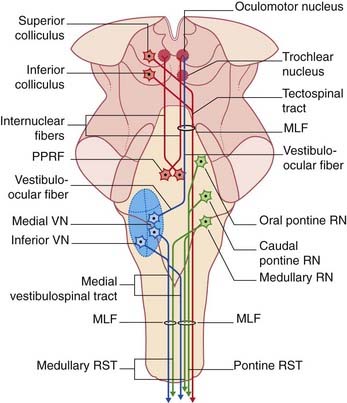

Figure 17.6 depicts the main components of the medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF). This fiber bundle extends the entire length of the brainstem, changing its fiber composition at different levels. This figure, too, may be consulted during study of the brainstem sections to be described, following inspection of C1 segment of the spinal cord.

Study guide

At each level, miniature replicas of the diagrams in Figure 17.7 are inserted to assist left–right orientation.

Overview of three pathways in the brainstem

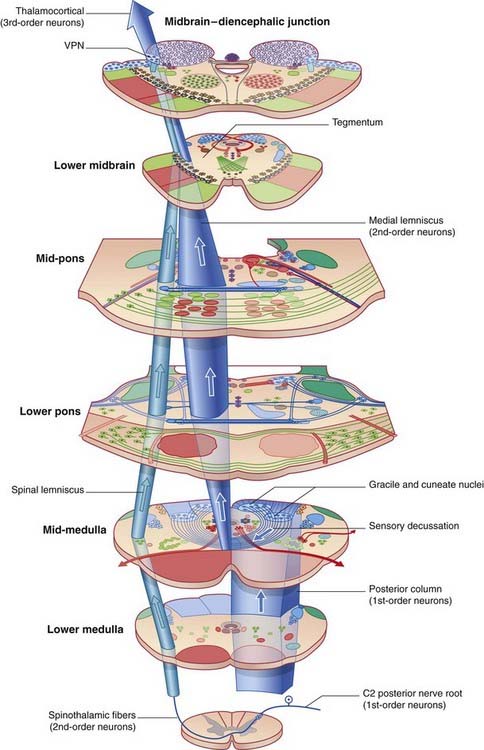

Figure 17.8 shows the posterior column–medial lemniscal and anterolateral pathways already described in Chapter 15. Recall that the latter comprises the lateral spinothalamic tract serving pain and temperature, and the anterior spinothalamic tract serving touch. Within the brainstem, the two are combined as the spinal lemniscus.

Figure 17.8 Posterior column–medial lemniscal and anterolateral pathways. VPN, ventral posterior nucleus of thalamus.

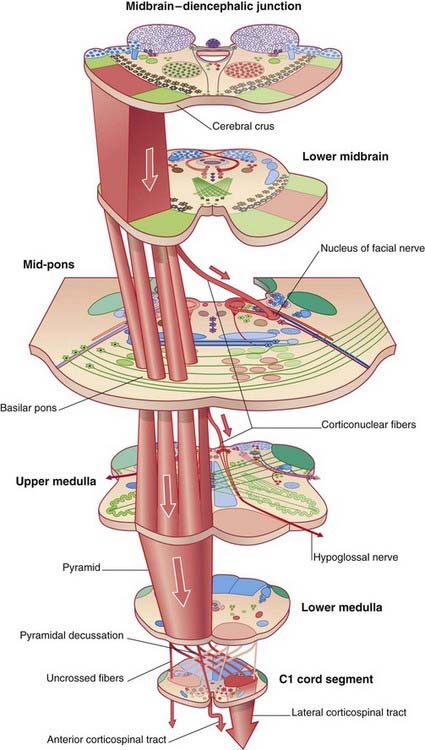

The corticospinal tract, treated in Chapter 16, is shown in Figure 17.9. Also included are corticonuclear projections to the facial and hypoglossal nuclei.

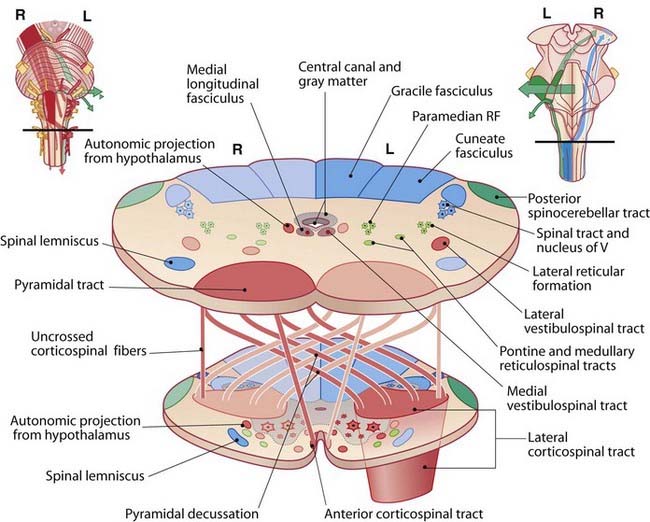

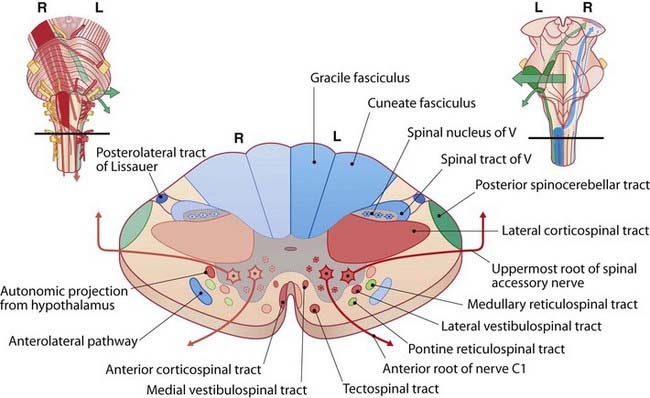

C1 Segment of Spinal Cord (Figure 17.10)

Blue

The gracile and cuneate fasciculi constitute the posterior column of the spinal cord on each side. Their axons are ipsilateral central processes of posterior root ganglion cells whose peripheral processes receive information from the large tactile nerve endings in the skin, including Meissner’s and Pacinian corpuscles, and from neuromuscular spindles and Golgi tendon organs. The fasciculi terminate in the gracile and cuneate nuclei (Figure 17.12).

Figure 17.10 C1 segment of spinal cord.

(After Noback CR et al. 1996, with permission of Williams & Wilkins.)

The spinothalamic (anterolateral) pathway comprises the anterior and lateral spinothalamic tracts. Unlike those in the posterior column, these two tracts comprise crossed axons. As indicated in Figure 15.10, the second-order neurons traverse the anterior white commissure at all segmental levels before ascending to the thalamus.

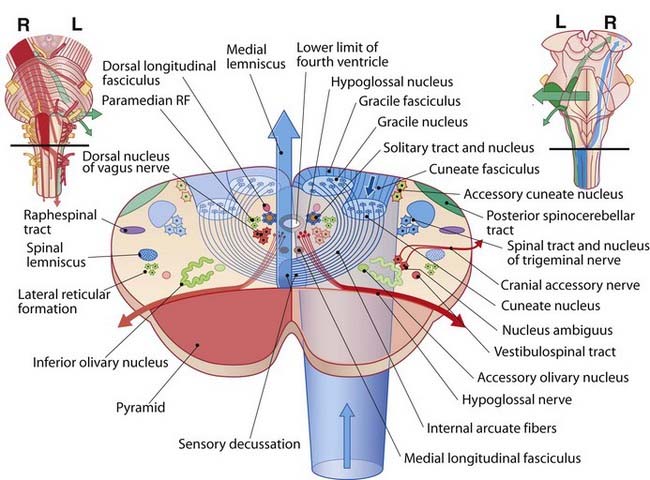

Middle of Medulla Oblongata (Figure 17.12)

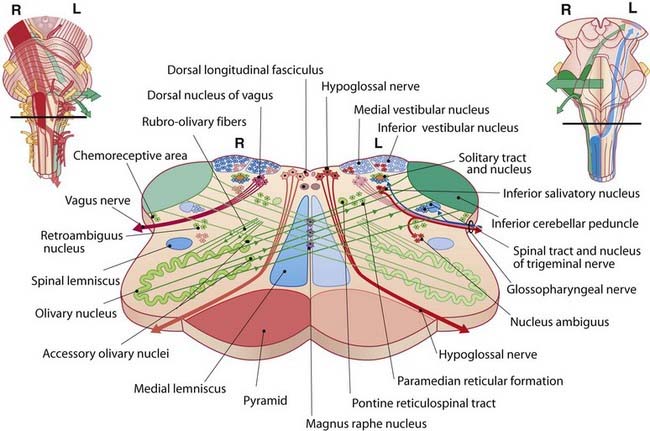

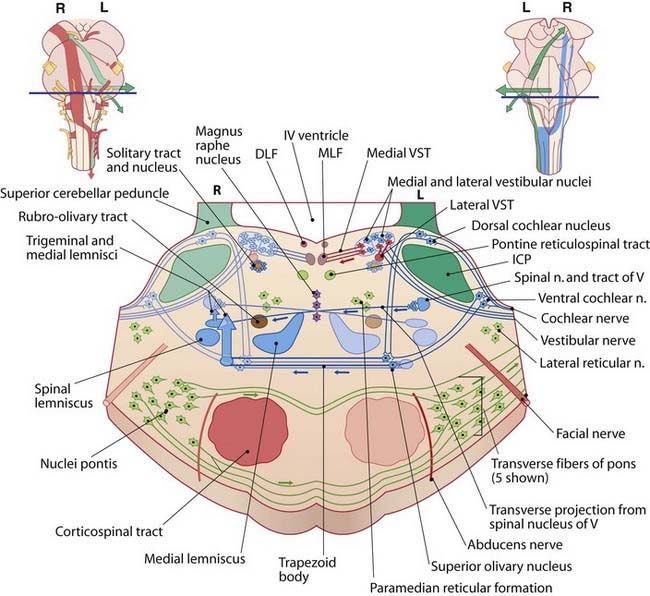

Pontomedullary Junction (Figure 17.14)

Blue

Previously seen are the medial and spinal lemnisci, also the spinal tract and nucleus of the trigeminal nerve. Novel are the lateral and trigeminal lemnisci. As explained in Ch. 20, the lateral lemniscus is an auditory fiber bundle ascending to the inferior colliculus, having crossed in the trapezoid body from the superior olivary nucleus. This nucleus is fed by auditory information from the dorsal and ventral cochlear nuclei, where the cochlear nerve terminates.

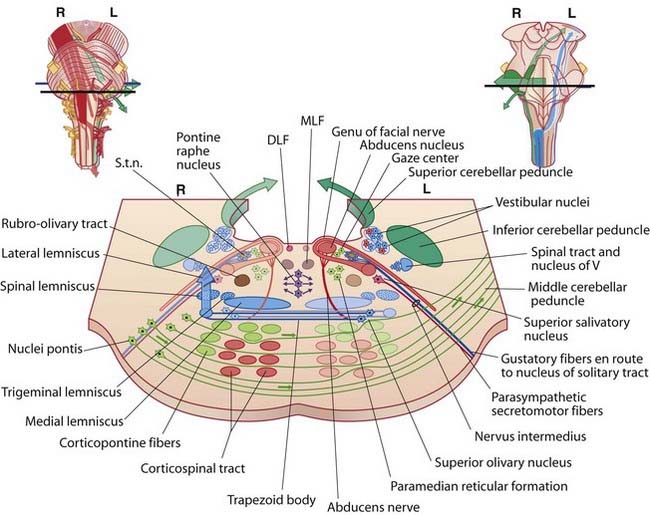

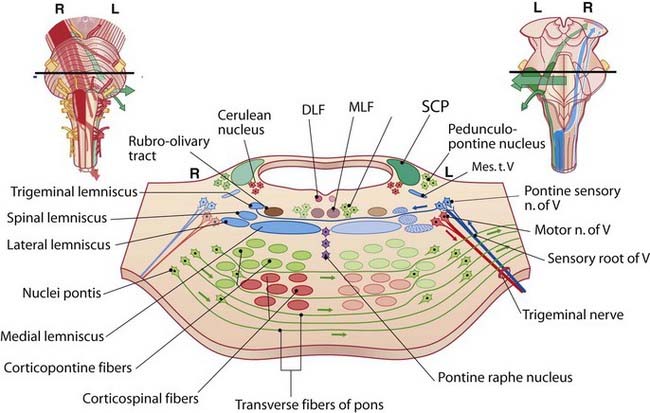

MID-Pons (Figure 17.15)

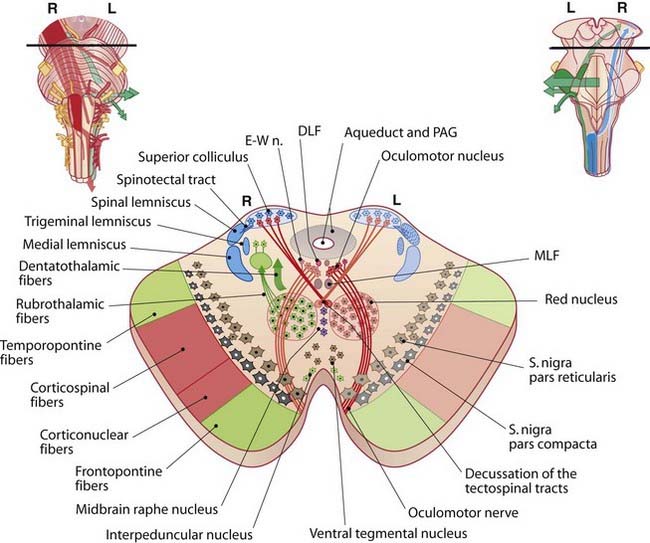

Upper Pons (Figure 17.16)

Blue

The mesencephalic tract of the trigeminal nerve (Mes. t. V) contains processes of unipolar neurons in the midbrain, as explained in Ch. 21.

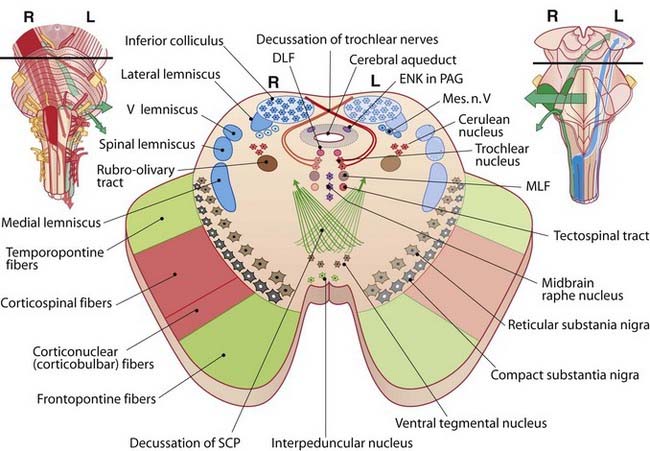

Lower Midbrain (Figure 17.17)

Brown/gray

The anterior tegmentum is occupied by compact and reticular elements of the substantia nigra. The compact part, comprising pigmented dopaminergic neurons, is the source of the nigrostriatal pathway to the corpus striatum. The nigrostriatal pathway loses both pigment and cells in those unfortunates bound for Parkinson’s disease (Ch. 33). The reticular part contains GABAergic neurons.

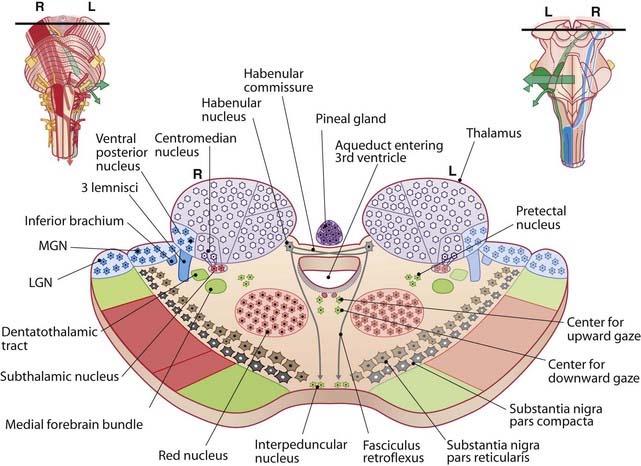

Midbrain–Thalamic Junction (Figure 17.19)

Red

The subthalamic nucleus receives an input from the centromedian nucleus of thalamus and projects to the lentiform nucleus. It may become overactive in Parkinson’s disease (cf. Ch. 33). The red nucleus and the contents of the crus cerebri are unchanged.

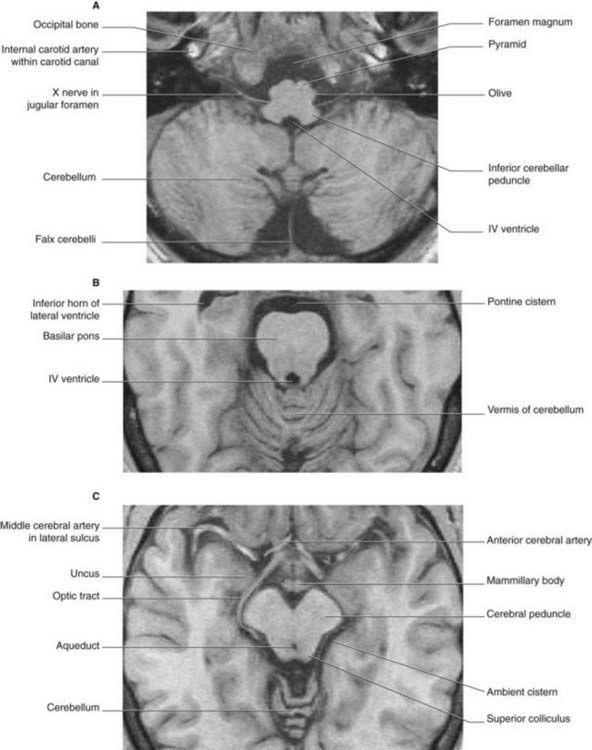

Orientation of Brainstem Slices in Magnetic Resonance Images (Figure 17.20)

Figure 17.20 shows brainstem slices in magnetic resonance images. Their orientation is the opposite of those in the preceding sections. In photographs and drawings, the convention is to represent anterior structures below. As already mentioned in Chapter 2, in magnetic resonance imaging scans, anterior structures are represented above.

Epilog

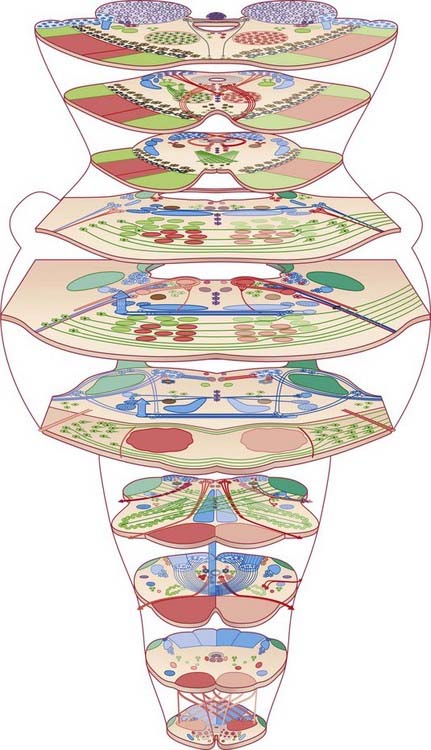

Figure 17.21 offers an unlabeled overview of the brainstem sections. Gentle skimmers may opt to photocopy lightly and to crayon pathways.

Core Information

Cell columns

Cranial nerve cell columns and their representations are as follows.