Chapter 491 Brain Tumors in Childhood

Etiology

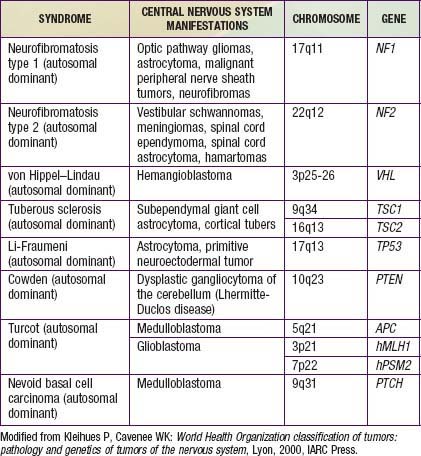

The etiology of pediatric brain tumors is not well defined. A male predominance is noted in the incidence of medulloblastoma and ependymoma. Familial and hereditary syndromes associated with increased incidence of brain tumors account for approximately 5% of cases (Table 491-1). Cranial exposure to ionizing radiation also is associated with a higher incidence of brain tumors. There are sporadic reports of brain tumors within families without evidence of a heritable syndrome. The molecular events associated with tumorigenesis of pediatric brain tumors are not known.

Pathogenesis

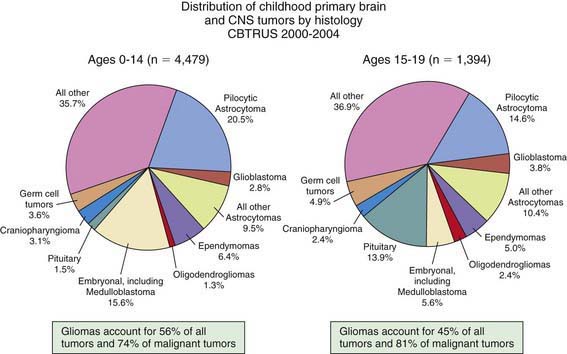

More than 100 histologic categories and subtypes of primary brain tumors are described in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the CNS. In children 0-14 yr, the most common tumors are pilocytic astrocytomas (PAs) and medulloblastoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs). In adolescents (15-19 yr), the most common tumors are pituitary tumors and PAs (Fig. 491-1).

Figure 491-1 Distribution of childhood primary brain and CNS tumors by histology.

(From Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States [CBTRUS]: CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2004-2006: February 2010 (PDF file). www.cbtrus.org/2010-NPCR-SEER/CBTRUS-WEBREPORT-Final-3-2-10.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2011.)

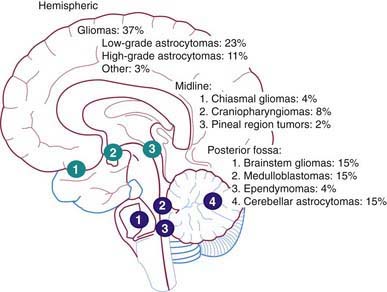

The Childhood Brain Tumor Consortium reported a slight predominance of infratentorial tumor location (43.2%), followed by the supratentorial location (40.9%), spinal cord (4.9%), and multiple sites (11%) (Fig. 491-2, Table 491-2). There are age-related differences in primary location of tumor. During the first year of life, supratentorial tumors predominate and include, most commonly, choroid plexus complex tumors and teratomas. In children 1-10 yr of age, infratentorial tumors predominate, owing to the high incidence of juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma and medulloblastoma. After 10 yr of age, supratentorial tumors again predominate, with diffuse astrocytomas most common. Tumors of the optic pathway and hypothalamus region, the brainstem, and the pineal-midbrain region are more common in children and adolescents than in adults.

Specific Tumors

Astrocytomas

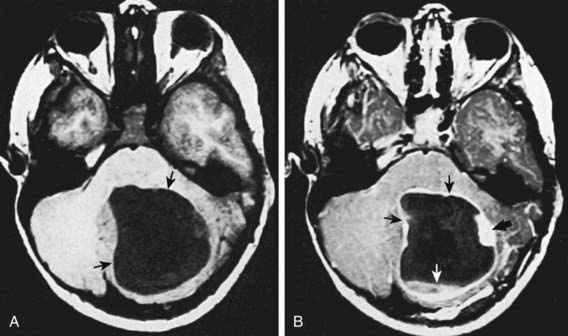

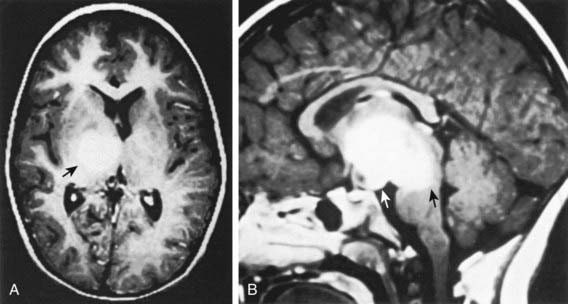

Low-grade astrocytomas (LGAs), the predominant group of astrocytomas in childhood, are characterized by an indolent clinical course. PA is the most common astrocytoma in children, accounting for about 20% of all brain tumors (Fig. 491-3). On the basis of clinicopathologic features using the WHO Classification System, PA is classified as a WHO grade I tumor. Although PA can occur anywhere in the CNS, the classic site is the cerebellum. Other common sites include the hypothalamic/third ventricular region and the optic nerve and chiasmal region. The classic but not exclusive neuroradiologic finding in PA is the presence of a contrast medium–enhancing nodule within the wall of a cystic mass (see Fig. 491-3). The microscopic findings include the biphasic appearance of bundles of compact fibrillary tissue interspersed with loose microcystic, spongy areas. The presence of Rosenthal fibers, which are condensed masses of glial filaments occurring in the compact areas, helps establish the diagnosis. PA has a low metastatic potential and is rarely invasive. A small proportion of these tumors can progress and develop leptomeningeal spread, particularly when they occur in the optic path region. A PA very rarely undergoes malignant transformation to a more aggressive tumor. A PA of the optic nerve and chiasmal region is a relatively common finding in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (15% incidence). Unlike in diffuse fibrillary astrocytomas, there are no characteristic cytogenetic abnormalities in PA nor are there any known molecular abnormalities. Other tumors occurring in the pediatric age group with clinicopathologic characteristics similar to those of PA include pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, desmoplastic cerebral astrocytoma of infancy, and subependymal giant cell astrocytoma.

The second most common astrocytoma is fibrillary infiltrating astrocytoma, which consists of a group of tumors characterized by a pattern of diffuse infiltration of tumor cells among normal neural tissue and potential for anaplastic progression. On the basis of their clinicopathologic characteristics, they are grouped as low-grade astrocytomas (WHO grade II), malignant astrocytomas (anaplastic astrocytoma; WHO grade III), and glioblastoma multiforme (GBM; WHO grade IV). Of this group, the fibrillary LGA is the second most common astrocytoma in children, accounting for 15% of brain tumors. Histologically, these low-grade tumors demonstrate greater cellularity than normal brain parenchyma, with few mitotic figures, nuclear pleomorphism, and microcysts. The characteristic MRI finding is a lack of enhancement after contrast agent infusion (Fig. 491-4). Molecular genetic abnormalities found among low-grade diffuse infiltrating astrocytomas include mutations of p53 and overexpression of platelet-derived growth factor α-chain and platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α. Fibrillary infiltrating astrocytoma has the potential to evolve into malignant astrocytoma, a development that is associated with cumulative acquisition of multiple molecular abnormalities.

Ependymal Tumors

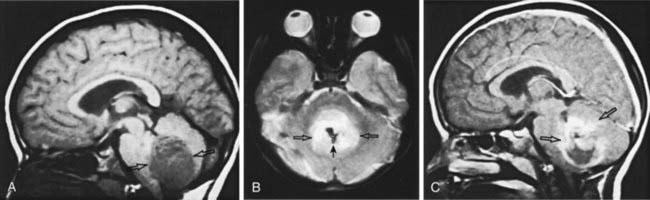

Ependymal tumors are derived from the ependymal lining of the ventricular system. Ependymoma (WHO grade II) is the most common of these neoplasms, occurring predominantly in childhood and accounting for 10% of childhood tumors. Approximately 70% of ependymomas in childhood occur in the posterior fossa. The mean age of patients is 6 yr, with approximately 40% of cases occurring in children <4 yr of age. The incidence of leptomeningeal spread approaches 10% overall. Clinical presentation can be insidious and often depends on the anatomic location of the tumor. MRI demonstrates a well-circumscribed tumor with variable and complex patterns of gadolinium enhancement, with or without cystic structures (Fig. 491-5). These tumors usually are noninvasive, extending into the ventricular lumen and/or displacing normal structures, sometimes leading to significant obstructive hydrocephalus. Histologic characteristics include perivascular pseudorosettes, ependymal rosettes, monomorphic nuclear morphology, and occasional nonpalisading foci of necrosis. Other histologic subtypes include anaplastic ependymoma (WHO grade III), which is much less common in childhood and is characterized by a high mitotic index and histologic features of microvascular proliferation and pseudopalisading necrosis. Myxopapillary ependymoma (WHO grade I) is a slow-growing tumor arising from the filum terminale and conus medullaris and appears to be a biologically different subtype. There are no well-defined characteristic cytogenetic or molecular genetic alterations in ependymoma, largely owing to their heterogenous nature, although various pathways have been implicated. Preliminary studies suggest that there are genetically distinct subtypes, exemplified by an association between alterations in the NF2 gene and spinal ependymoma. Surgery is the primary treatment modality, with extent of surgical resection a major prognostic factor. Two other major prognostic factors are age, with younger children having poorer outcomes, and tumor location, with localization in the posterior fossa, which often is seen in young children, associated with poorer outcomes. Surgery alone is rarely curative. Multimodal therapy incorporating irradiation with surgery has resulted in long-term survival in approximately 40% of patients with ependymoma undergoing gross total resection. Recurrence is predominantly local. Ependymoma is sensitive to a spectrum of chemotherapeutic agents; the role of chemotherapy in multimodal therapy of ependymoma is still unclear. Current investigations are directed toward identification of optimal radiation dose, surgical questions addressing the use of second-look procedures after chemotherapy, and further evaluation of classic as well as novel chemotherapeutic agents.

Embryonal Tumors

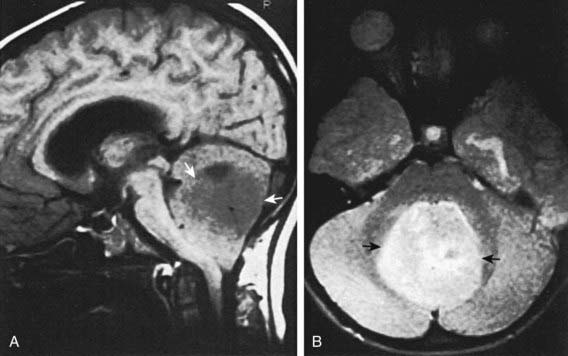

Medulloblastoma, which accounts for 90% of embryonal tumors, is a cerebellar tumor occurring predominantly in males and at a median age of 5-7 yr. Most of these tumors occur in the midline cerebellar vermis; however, older patients may present with tumors in the cerebellar hemisphere. CT and MRI demonstrate a solid, homogeneous, contrast medium–enhancing mass in the posterior fossa causing 4th ventricular obstruction and hydrocephalus. Up to 30% of patients with medulloblastoma present with neuroimaging evidence of leptomeningeal spread. Among a variety of diverse histologic patterns of this tumor, the most common is a monomorphic sheet of undifferentiated cells classically noted as small, blue, round cells. Neuronal differentiation is more common among these tumors and is characterized histologically by the presence of Homer Wright rosettes and by immunopositivity for synaptophysin. An anaplastic variant is often more aggressive and may be associated with worse prognosis. Patients present with signs and symptoms of increased ICP (i.e., headache, nausea, vomiting, mental status changes, and hypertension) and cerebellar dysfunction (i.e., ataxia, poor balance, dysmetria). Standard clinical staging evaluation includes MRI of the brain and spine, both preoperatively and postoperatively, as well as lumbar puncture after the increased ICP has resolved (Fig. 491-6). The Chang staging system, originally based on surgical information, has been modified to incorporate information from neuroimaging to identify risk categories. Clinical features that have consistently demonstrated prognostic significance include age at diagnosis, extent of disease, and extent of surgical resection. Patients <4 yr of age have a poor outcome, partly as the result of a higher incidence of disseminated disease on presentation and past therapeutic approaches that have used less intense therapies. Patients with disseminated disease at diagnosis (M >0), including positive CSF cytologic result alone (M1), have a markedly worse outcome than those patients with no dissemination (M0). Similarly, patients with gross residual disease after surgery have worse outcomes than those in whom surgery achieved gross total resection of disease.

Tumors of the Brainstem

Tumors of the brainstem are a heterogeneous group of tumors that account for 10-15% of childhood primary CNS tumors. Outcome depends on tumor location, imaging characteristics, and the patient’s clinical status. Patients with these tumors may present with motor weakness, cranial nerve deficits, cerebellar deficits, and/or signs of increased ICP. On the basis of MRI evaluation and clinical findings, tumors of the brainstem can be classified into four types: focal (5-10% of patients); dorsally exophytic (5-10%); cervicomedullary (5-10%); and diffuse intrinsic (70-85%) (Fig. 491-7). Surgical resection is the primary treatment approach for focal and dorsally exophytic tumors and leads to a favorable outcome. Histologically, these two groups usually are low-grade gliomas. Cervicomedullary tumors, owing to their location, may not be amenable to surgical resection but are sensitive to radiation therapy. Diffuse intrinsic tumors, characterized by the diffuse infiltrating pontine glioma, are associated with very poor outcome independent of histologic diagnosis. These tumors are not amenable to surgical resection. Biopsy in children in whom MRI shows a diffuse intrinsic tumor is controversial and is not recommended unless there is suspicion of another diagnosis, such as infection, demyelination, vascular malformation, multiple sclerosis, or metastatic tumor. These diagnoses are much more common in adults. The standard approach for treatment of diffuse infiltrating pontine gliomas has been radiation therapy, and median survival with this treatment is 12 mo, at best. Use of chemotherapy, including high-dose chemotherapy with blood stem cell rescue, has not yet been of survival benefit in this group of patients. Current approaches include evaluation of investigational agents alone or in combination with radiation therapy, similar to approaches being pursued in patients with malignant gliomas.

Ansell P, Johnston T, Simpson J, et al. Brain tumor signs and symptoms: analysis of primary health care records from the UKCCS. Pediatrics. 2010;125:112-119.

Biegal JA, Zhou J-Y, Rorke LB, et al. Germ-line and acquired mutations of INI1 in atypical teratoid and rhabdoid tumours. Cancer Res. 1999;59:74-79.

Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States. CBTUS statistical report: primary brain tumors in the United States, 2000–2004. Hinsdale, IL: Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States; 2008.

de Bont JM, Packer RJ, Michiels EM, et al. Biological background of pediatric medulloblastoma and ependymoma: a review from translational research perspective. Neuro-Oncology. 2008;10:1040-1060.

Eberhart CG, Kratz J, Want Y, et al. Histopathological and molecular prognostic markers in medulloblastoma: c-myc, N-myc, TrkC, and anaplasia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:4441-4449.

Ellison DW, Onilude OE, Lindsey JC, et al. Beta-catenin status predicts a favorable outcome in childhood medulloblastoma: the United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group Brain Tumour Committee. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7951-7957.

Fernandez-Teijeiro A, Betensky RA, Sturla LM, et al. Combining gene expression profiles and clinical parameters for risk stratification in medulloblastomas. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:994-998.

Frazier JL, Lee J, Thomale UW, et al. Treatment of diffuse intrinsic brainstem gliomas: failed approaches and future strategies. J Neurosurg. 2009;3:259-269.

Freeman CR, Perilongo G. Chemotherapy for brain stem gliomas. Childs Nerv Syst. 1999;15:545-553.

Gajjar A, Hernan R, Kocak M, et al. Clinical, histopathologic, and molecular markers of prognosis: toward a new disease risk stratification system for medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:984-993.

Gerber NU, Zehnder D, Zuzak TJ, et al. Outcome in children with brain tumours diagnosed in the first year of life: long-term complications and quality of life. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:582-589.

Gilbertson S, Wickramasinghe C, Hernan R, et al. Clinical and molecular stratification of disease risk in medulloblastoma. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:705-712.

Grill J, Sainte-Rose C, Jouvet A, et al. Treatment of medulloblastoma with postoperative chemotherapy alone: an SFOP prospective trial in young children. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:573-580.

Gurney JC, Smith MA, Bunin GR, Reis LAG, Smith MA, Gurney JC, et al, editors. Cancer survival and incidence among children and adolescents: United States SEER program 1975–1995. National Cancer Institute SEER Program, Bethesda, MD, 1999, 51-63. NIH publication No. 99-4649

Liu AK, Macy ME, Foreman NK. Bevacizumab as therapy for radiation necrosis in four children with pontine gliomas. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:1148-1154.

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestier OD, et al. WHO Classification of tumours of the central nervous system, ed 4. Lyon: IARC Press; 2007.

Mellinghoff IK, Wang MY, Vivanco I, et al. Molecular determinations of the response of glioblastomas to EGFR kinase inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2012-2024.

Merchant TE, Mulhern RK, Krasin MJ, et al. Preliminary results from a phase II trial of conformal radiation therapy and evaluation of radiation-related CNS effects for pediatric patients with localized ependymoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;15:3156-3162.

Nakamura M, Shimada K, Ishida E, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of pediatric astrocytic tumors. Neuro-Oncology. 2007;9:112-123.

Packer RJ, Cohen BH, Coney K. Intracranial germ cell tumors. Oncologist. 2000;5:312-320.

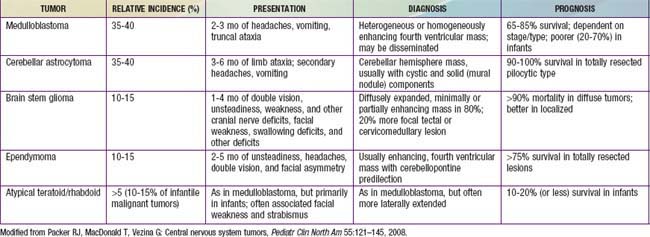

Packer RJ, MacDonald T, Vezina G. Central nervous system tumours. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55:121-145.

Pasche B, Myers RM. One step forward toward identification of the genetic signature of glioblastomas. JAMA. 2009;302:325-326.

Paugh BS, Qu C, Jones C, et al. Integrated molecular genetic profiling of pediatric high-grade gliomas reveals key differences with the adult disease. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(18):3061-3068.

Pizer B, Clifford S. Medulloblastoma: new insights into biology and treatment. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2008;93:137-144.

Pollack IF, Finkelstein SD, Woods J, et al. Expression of p53 and prognosis in children with malignant gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:420-426.

Rutkowski S, Bode U, Deinlein F, et al. Treatment of early childhood medulloblastoma by postoperative chemotherapy alone. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:978-986.

Rudin CM, Hann CL, Laterra J, et al. Treatment of medulloblastoma with hedgehog pathway inhibitor GDC-0449. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1173-1178.

Sanai N, Mirzadeh Z, Berger MS. Functional outcome after language mapping for glioma resection. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:18-26.

Shaw EG, Wisoff JH. Prospective clinical trials of intracranial low-grade glioma in adults and children. Neurooncology. 2003;5:153-160.

Shete S, Hosking FJ, Robertson LB, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five susceptibility loci for glioma. Nat Genet. 2009;41:899-904.

Short S, Tobias J. Radiosurgery for brain tumors. BMJ. 2010;341:c3247.

Strother DR, Pollac IF, Fisher PG, et al. Tumors of the central nervous system. In Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors: Principles and practice of pediatric oncology, ed 5, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987-996.

Wilne S, Koller K, Collier J, et al. The diagnosis of brain tumours in children: a guideline to assist healthcare professionals in the assessment of children who may have a brain tumour. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:534-539.

Yan H, Parsons W, Jin G, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:765-773.

Zebrack BJ, Gurney JG, Oeffinger K, et al. Psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood brain cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivors Study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:999-1006.

Zelcer S, Cataudella D, Cairney AEL, et al. Palliative care of children with brain tumors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:223-230.