52 Brain Tumors

Malignant Brain Tumors

Gliomas

Pathology

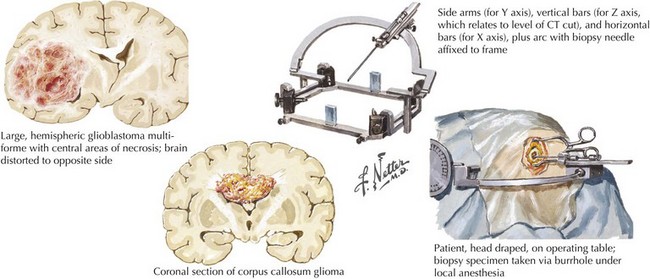

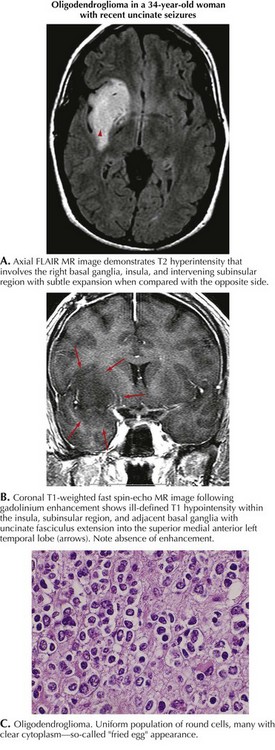

Gliomas typically exhibit features of astrocytes, or oligodendrocytes, or both (mixed glioma) (Fig. 52-1). Microscopically, gliomas appear as diffusely infiltrating cancers of three types: astrocytic, oligodendroglial, and oligoastrocytic (combining the morphologic features of both oligodendroglioma and astrocytoma).

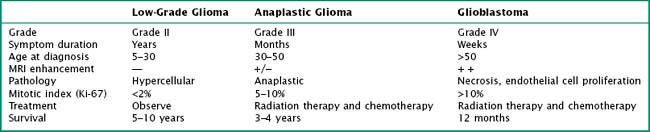

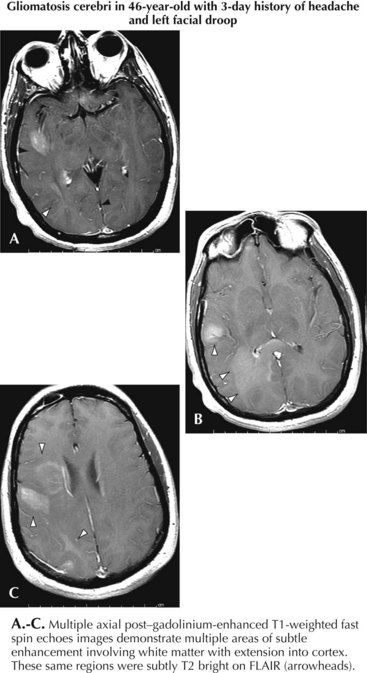

The World Health Organization uses a three-tiered classification system based on histologic criteria that divides these tumors into low-grade glioma, anaplastic glioma, and glioblastoma multiforme (Table 52-1). Low-grade tumors may contain a high density of almost normal-appearing cells. Here the percentage of cells that are dividing (as determined by mib-1 or KI-67 staining) is often 2% or less. Anaplastic gliomas exhibit more atypical cells, with pleomorphic nuclei having growth rates in the 5–10% range but no evidence of necrosis. Gliomas with high growth rates (>10% mitotic figures) and necrosis are classified as glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). The less common pilocytic astrocytomas are a separate category of glioma that are histologically characterized by Rosenthal’s fibers, usually occur in children, and often have a good prognosis if surgical resection can be achieved. Tumor grade is the most reliable predictor of prognosis. Even if the lesion cannot be safely excised, a needle biopsy is often indicated. Gliomas are not staged as other cancers are because they rarely metastasize outside the CNS. Analysis of tumor samples for genetic abnormalities can help predict response to therapy and will likely lead to a better classification system for gliomas. This classification is valuable prognostically; low-grade gliomas have median survivals of 5–15 years, anaplastic gliomas 2–5 years, and GBM 12–18 months.

Glioblastoma

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis

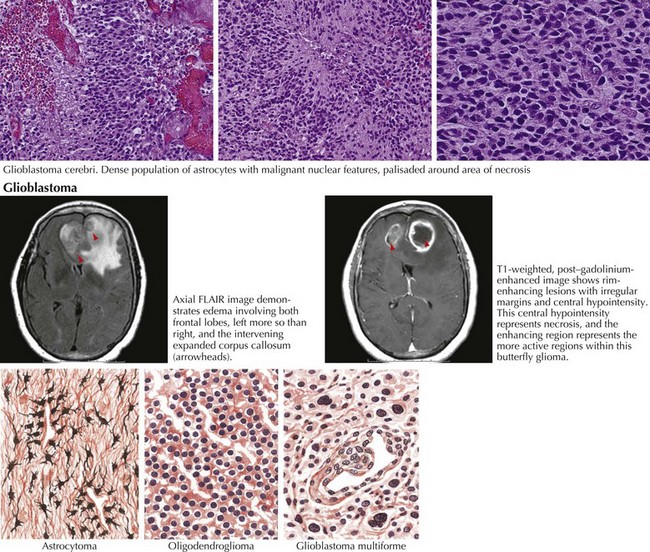

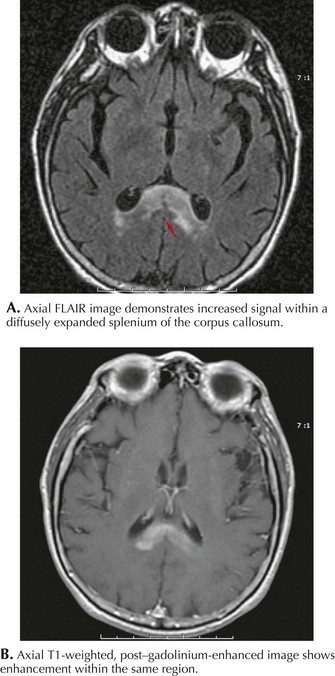

MRI is the most specific diagnostic modality (Fig. 52-2). On most occasions, one sees focal heterogeneous irregular-margined cystic mass lesions with perilesion edema, gadolinium rim enhancement, and often enough mass effect to produce a transtentorial herniation. In contrast, the occasional patients with gliomatosis cerebri have a characteristic diffusely abnormal MRI picture characterized by multiple areas of subtle white matter enhancement with extension into the cortical mantle, extending far beyond what their clinical presentation usually dictates (Fig. 52-3).

Low-Grade Glioma

Clinical Vignette

This 34-year-old right-handed woman presented with generalized seizures. Several months earlier, she noted episodes of an unusual smell but these did not cause her immediate concern. Brain MRI demonstrated a right temporal lobe lesion, bright on T2 and FLAIR imaging but hypointense on T1, with no evidence of enhancement after gadolinium (Fig. 52-4). The patient was treated with oxcarbazepine and admitted to the hospital. Open biopsy was nondiagnostic but subsequent temporal lobectomy revealed an oligodendroglioma with a Ki-67 index of 3.8%. Postoperatively, the patient was treated with monthly temozolomide for 1 year. She is now receiving no treatment and has been clinically and radiographically stable for 2 years.

Clinical Presentation/Pathology

Low-grade gliomas (LGGs) are slow growing with a symptom history that can extend from months to years. Although easily defined by MRI (see Fig. 52-4), LGGs often do not enhance with gadolinium. Their course is usually relatively stable for several years before eventually progressing. At time of diagnosis, LGGs have a much better prognosis than GBM. However, eventually LGGs progress to become glioblastomas with their inherent poor prognosis. Histologically, low-grade gliomas are classified as astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, or oligoastrocytomas (mixed glioma). A low mitotic index, younger patient age, and a supratentorial nonelegant locus (i.e., not affecting language function) that is amenable to resection predict a longer progression-free survival.

Anaplastic Glioma

Clinical Vignette

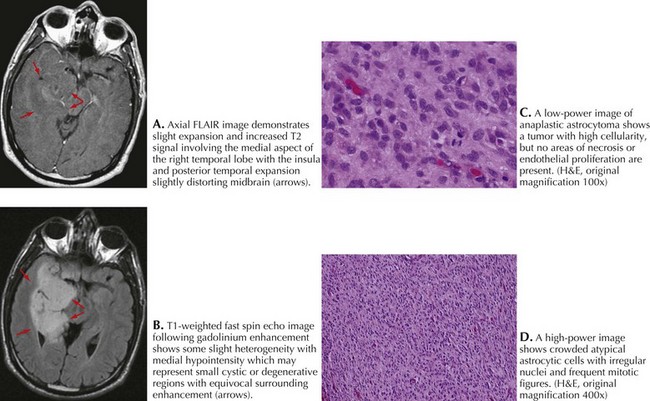

A 49-year-old right-handed man presented with 5 weeks of numbness and weakness in the left leg. Examination revealed decreased strength and slowed rapid movements of his left foot. There was extinction to touch and loss of joint position sense. Brain MRI revealed a 3 × 4-cm cystic mass centered in the medial aspect of the right parietal lobe and heterogeneous enhancement with gadolinium (Fig. 52-5).

Lesion resection revealed an anaplastic astrocytoma (Fig. 52-5). Postoperatively, he was treated with a combination of RT and concomitant temozolomide. He was treated monthly for 1 year and is now receiving the same dose at 8-week intervals. He is neurologically intact and radiographically stable 3 years after diagnosis.

Primary Cns Lymphoma

MRI in PCNSL patients usually demonstrates a homogeneously enhancing lesion(s) often adjacent to a ventricle (Fig. 52-6). A positive cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cytology is typically found in 25–50% of these individuals. Systemic PCNSL involvement is rare; therefore computed tomography (CT) or MRI scanning of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is not warranted. Biopsy is essential to make the diagnosis. A large resection is usually not indicated as most of these tumors respond well to chemotherapy and/or RT. In some immunocompetent patients these enhancing brain lesions can disappear either spontaneously or with corticosteroid therapy. For this reason, if PCNSL is suspected, biopsy should be performed prior to treatment with corticosteroids.

Other Primary Brain Tumors

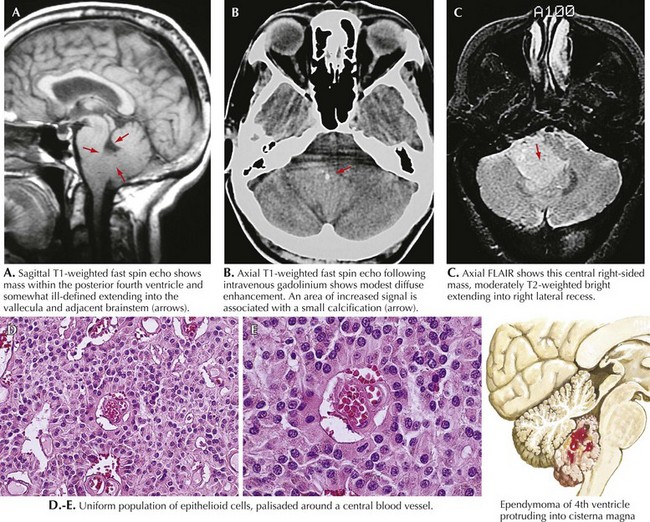

Ependymoma

MRI is the study of choice (Fig. 52-7). Surgical resection is the primary treatment; however, tumor location determines whether a complete resection is achievable. The extent of tumor resection is the most important indicator of the eventual clinical course. Surgical resection of a myxopapillary ependymoma frequently results in a cure. Indicators of poor prognosis include incomplete resection and CSF spread. Such patients require either local or craniospinal RT. Chemotherapy is seldom used at the time of diagnosis.

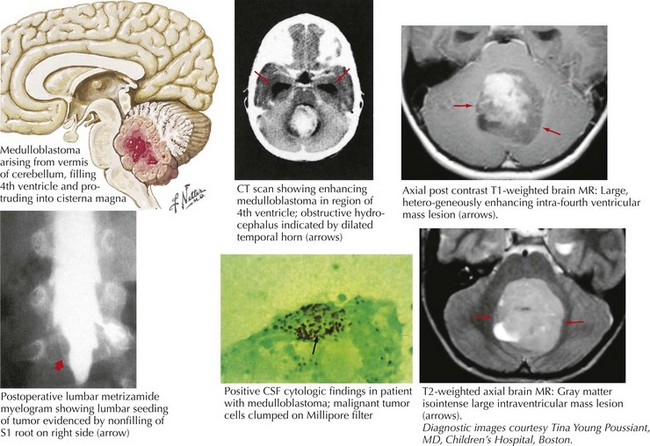

Medulloblastoma

These are a class of uncommon primitive neuroectodermal tumors that usually occur in the posterior fossa, often in the midline. Typically, these patients present with double vision, ataxia, hydrocephalus, nausea, and vomiting (Fig. 52-8). These tumors comprise 3% of all primary brain tumors and are significantly more prominent in children. Brain MRI usually reveals a homogeneously enhancing mass situated in the roof of the fourth ventricle, often with some degree of hydrocephalus. Pathologically, medulloblastomas are characterized by sheets of small, poorly differentiated cells with minimal cytoplasm.

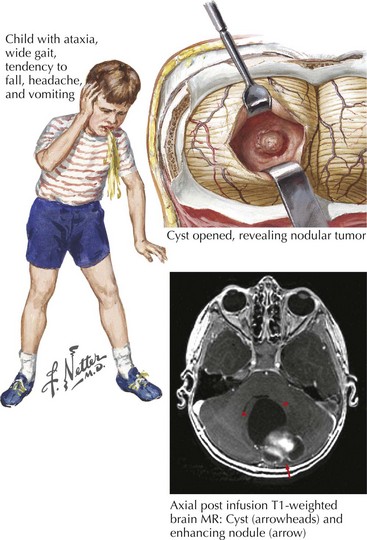

Cerebellar Astrocytoma

Most childhood primary brain tumors are in the glioma family, and many of these occur within the cerebellum (Fig. 52-9). Pilocytic astrocytomas are the most common posterior fossa variant. These tend to arise within the cerebellar hemisphere. A second form of cerebellar astrocytoma, the diffuse or fibrillary form, often arises in the midline and produces obstruction of the fourth ventricle and hydrocephalus. Cerebellar astrocytomas are often cystic in appearance, with an enhancing mural nodule.

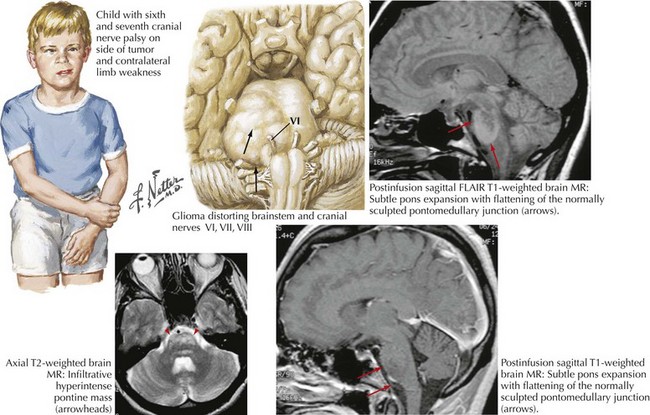

Pontine Glioma

These serious tumors primarily occur in childhood but are on rare occasions found in adults. They tend to be higher grade tumors that expand the pons and infiltrate into the surrounding tissue (Fig. 52-10). Presenting symptoms are consistent with their location, namely, hydrocephalus from fourth ventricle obstruction, or long tract signs from impairment of corticospinal axonal pathways. Isolated cranial neuropathies, particularly sixth and seventh nerve lesions, may also occur from compression of brainstem nuclei. The infiltrative nature of these tumors often precludes any degree of significant surgical resection. Unfortunately RT is usually ineffective at achieving long-term growth control.

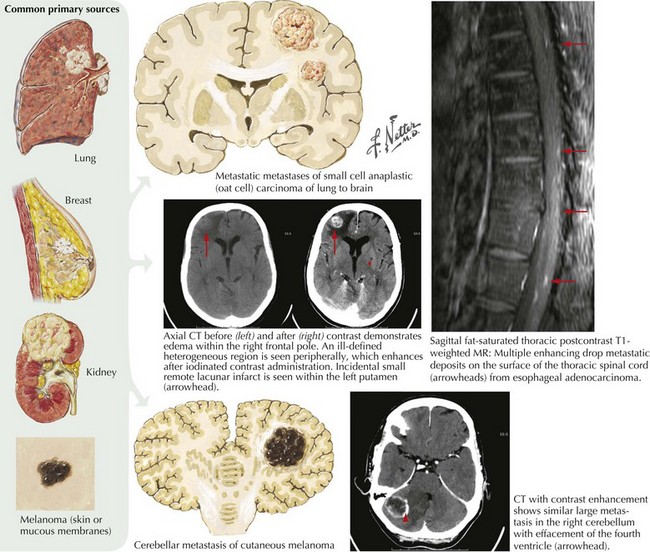

Metastatic Brain Tumors

Clinical Vignette

Lung cancer is the most common primary tumor that metastasizes to the CNS (50%), followed by breast (33%), colon (9%), and melanoma (7%) (Fig. 52-11). The interval between the primary diagnosis and presentation of a CNS metastasis depends on the tumor type. For lung cancer, the median interval is 4 months; for breast cancer, 3 years. CNS metastasis is an indicator of poor prognosis and portends a survival of <6 months for most patients.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Meningeal gadolinium enhancement portends the presence of carcinomatous leptomeningeal invasion with the important exception of the low pressure syndrome (see below). The malignant enhancement usually has a very irregular character in contrast to the very smooth enhancement seen with the very benign low pressure syndrome (see Fig. 52-23). CSF cytologic analysis, in most instances of leptomeningeal cancer, demonstrates an increased number of malignant cells, thus confirming the diagnosis. Sometimes the initial CSF in this setting is negative. Here, if there is a high clinical suspicion, one must make repeated spinal taps. On one occasion we had a patient who required six different CSF cytologic examinations before a specific diagnosis could be made.

Benign Brain Tumors

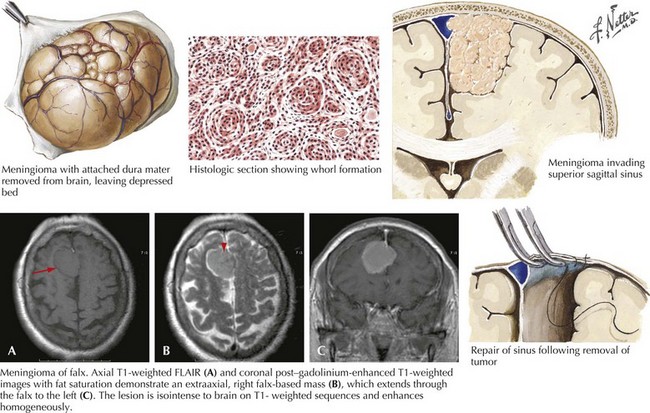

Meningiomas

Demographics

Classically, these are slow-growing tumors attaining large size before becoming symptomatic; however, occasionally they seem to grow much more rapidly, especially during pregnancy. Meningiomas arising adjacent to the frontal lobe are particularly prone to being clinically silent because of the disproportionately large size of this part of the brain where there is much more tissue to be “forgiving.” Such a slowly enlarging lesion can gradually compress brain tissue without producing definitive symptoms in this “clinically silent” part of the brain. A good example occurs when a meningioma affects the prefrontal cortex. Subtle personality changes gradually develop that are only appreciated in retrospect. However, if the tumor lies adjacent to overtly functional brain tissue, such as the motor cortex, symptoms may present relatively early (Fig. 52-12).

Pituitary Adenoma

Clinical Presentation

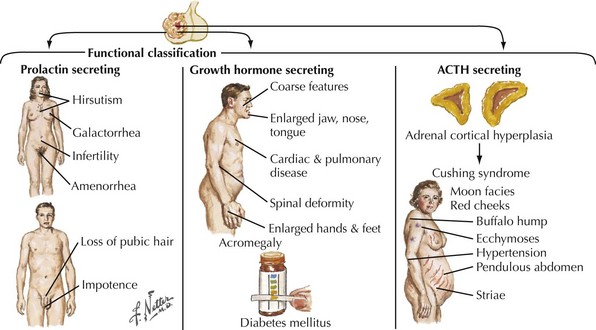

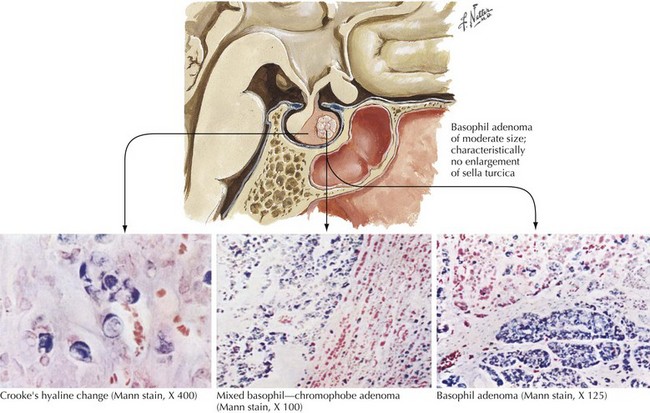

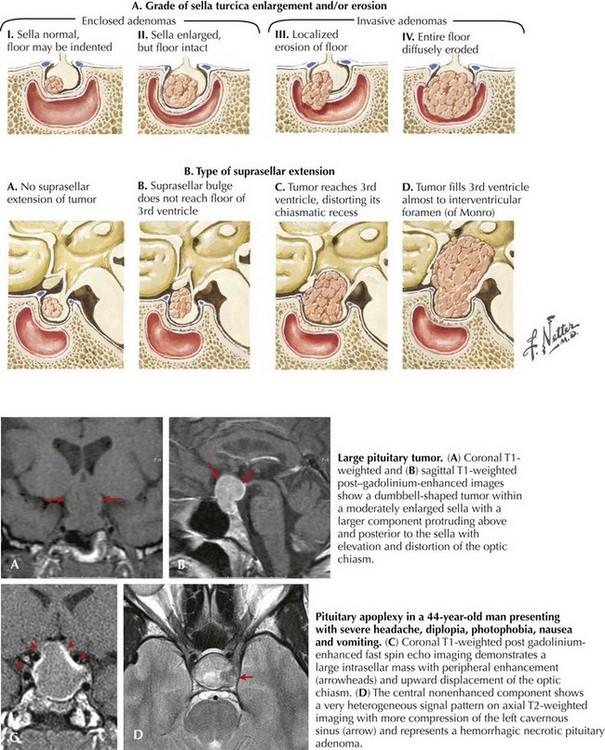

Endocrinologically active tumors secrete hormones, often resulting in symptoms appropriate to the target glands to which the specific active cell type is directed. The clinical picture characteristic of a pituitary tumor depends on its primary cell type of origin (Fig. 52-13). For example, in the preceding vignette, abnormal galactorrhea was directly related to the production of increased amounts of prolactin-secreting tumor cells. These are one of the most common endocrinologically active pituitary tumors. Pituitary acidophil adenomas that primarily secrete growth hormone lead to the clinical syndrome of acromegaly with gigantism and/or enlarged bony features in the face, skull, and hands. Cushing disease with truncal obesity, cervical buffalo hump, moon-like flushed facies, proximal muscle weakness, hypokalemia, and glucose intolerance occurs when pituitary adenomas primarily secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone, leading to increased circulating serum cortisol (Fig. 52-14).

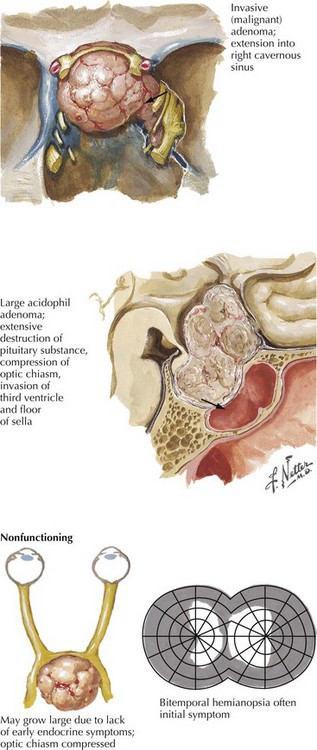

Chromophobe adenomas are not endocrinologically productive; however when an adenoma develops here initially these tumors may be clinically silent. Although histologically benign, pituitary adenomas may have serious consequences when undiagnosed early on because their proximity to the optic nerves, the optic tracts, the cavernous sinus, and the temporal lobe tip may lead to significant neurologic consequences. The nonendocrinologically active tumors frequently reach a large size before symptoms develop (Fig. 52-15). Typically, their diagnosis depends on the presentation of mass effect symptoms. Bitemporal visual field cuts result when pituitary macroadenomas extend above the sella and compress the overlying optic chiasm.

Pituitary apoplexy is a relatively rare clinical presentation for pituitary adenomas. Classically, this is an acute-onset severe headache associated with significant visual impairment and decreased mental status. Sometimes this may well mimic a ruptured intracranial aneurysm. The cause is often a hemorrhage into a preexisting pituitary adenoma (Fig. 52-16).

Diagnostic Approach

Patients with suspected pituitary adenomas are evaluated with a combination of imaging and endocrinologic studies. Brain MRI is the best radiographic modality to identify pituitary tumors. Sella expansion, diminished enhancement within the sella, and shifting of the pituitary stalk to one side are all clues for a possible pituitary microadenoma In contrast, macroadenomas (measuring >25 mm) extend above the sella or into the cavernous sinus on either side of the sella and are easily identified with MRI (see Fig. 52-16). A thorough endocrine evaluation includes serum levels of prolactin, follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, cortisol, and growth hormone and thyroid function parameters.

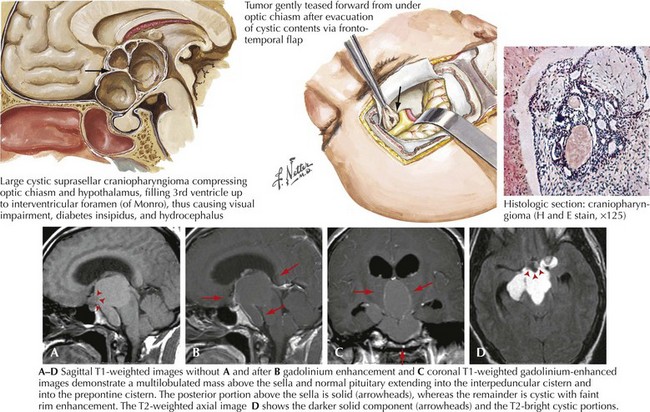

Craniopharyngioma

The radiographic features of craniopharyngiomas distinguish them from other tumors of the suprasellar region (Fig. 52-17). Cystic changes, variable-contrast enhancement, and calcification seen on CT occur frequently.

Acoustic Neuromas/Vestibular Schwannoma

Demographics

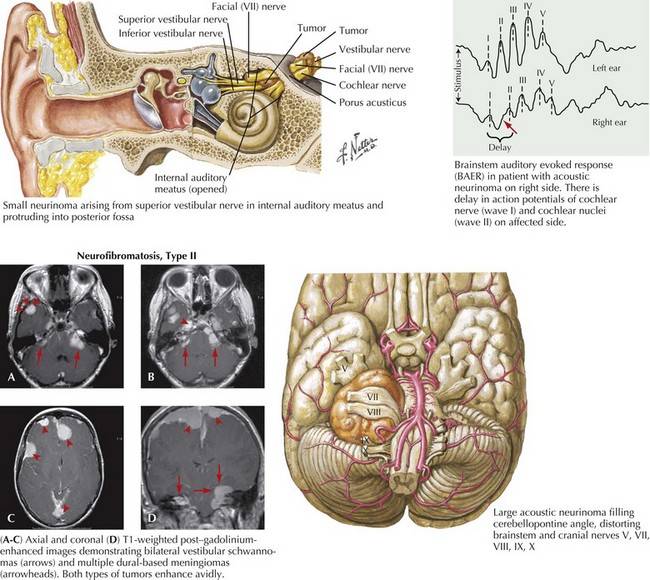

Acoustic neuromas are the second most common of the benign brain tumors. These comprise approximately 6–8% of all primary intracranial neoplasms. There is a 2% incidence within the general population. Most commonly, acoustic neuromas present between ages 40 and 60 years. With the exception of patients who have genetically determined neurofibromatosis type II, it is unusual to see a patient have an acoustic neuroma become clinically recognized before age 20 years. The non–genetically determined acoustic neuromas predominantly develop unilaterally. In contrast, those occasional patients with type II neurofibromatosis often have bilateral acoustic neuromas. These benign tumors arise from the Schwann cells of the vestibular nerve within the eighth cranial nerve complex (Fig. 52-18).

Diagnostic Studies

MRI is the primary diagnostic modality. Its clarity, resolution, and ability to scan in multiple planes allow for three-dimensional assessment. Because lesion size and its relation to adjacent neurologic structures, such as the pons and various cranial nerves, often determine treatment, MRI is also a therapeutically very crucial investigational modality. Typically, these well-demarcated, homogeneously enhancing tumors arise within the cerebellar pontine angle and extend into the internal auditory canal (see Fig. 52-18).

Other Benign Intracranial Tumors

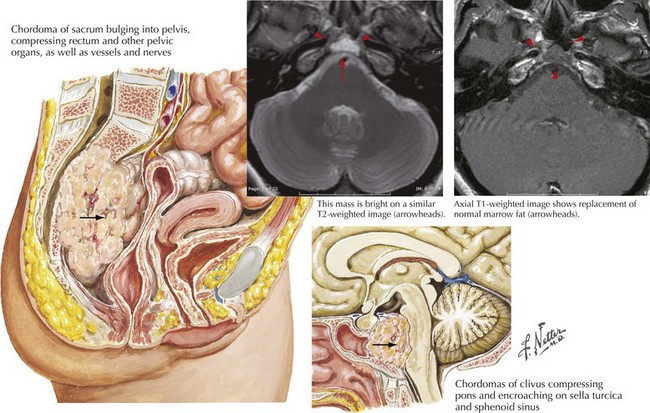

Chordoma

These are very rare usually benign tumors that have embryologic elements similar to intervertebral disks. Typically, chordomas develop either on the clivus of the skull base or the sacrum (Fig. 52-19). Intracranial chordomas arise from within the skull bone and cause local destruction. Concomitantly these tumors enter the intradural space, where they sometimes affect the brainstem and cranial nerves.

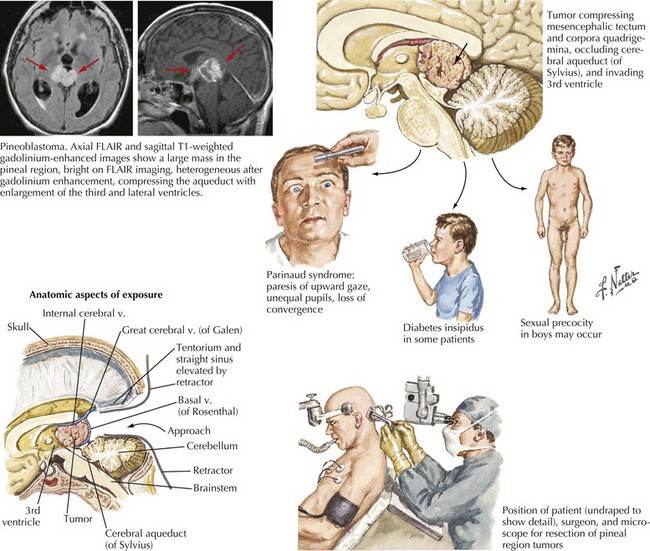

Pineal Region Tumors

Tumors occurring in the region of the pineal gland are uncommon, comprising approximately 1% of intracranial tumors. These neoplasms, having a histologically mixed benignancy, include germ cell tumors, glial neoplasms, and pineal parenchyma tumors (Fig. 52-20). Germ cell origin tumors are the most common, usually occurring in younger patients. Gliomas can arise from within the pineal gland itself or from the glial cells in the surrounding tissue. In this region, glial tumors tend to be of lower grade. Tumors arising from the pineal parenchyma comprise approximately 20% of pineal region tumors.

Colloid Cysts

These are histologically benign third ventricle tumors that arise from embryologic development remnants. The cells lining the walls of the cyst are ciliated. Third ventricular lesions of this type typically do become symptomatic during adulthood but can be seen in children. Posturally precipitated headaches, with concomitant symptoms and signs of hydrocephalus are the most common clinical presentations for colloid cysts. Because of their inherent intraventricular location, these cysts lead to CSF obstruction at the foramina of Monro (Fig. 52-21).

Differential Diagnosis

Pseudotumor Cerebri/Idiopathic Intracranial Hypotension, Intracranial Hypotension, and Other Brain Lesions

Clinical Vignette

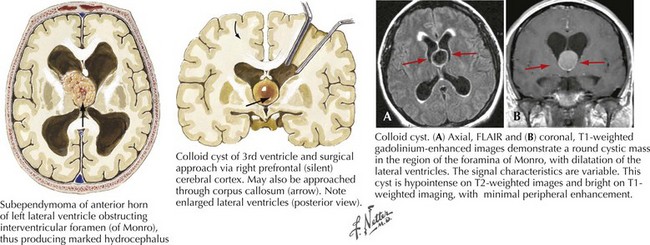

An obese 42-year-old woman presented with a 2-month history of increasingly severe headaches and intermittent double vision. Her headaches were exacerbated by postural changes, particularly bending forward or jarring in the car. Bilateral limitation of adduction of her eyes compatible with sixth cranial nerve paresis and modest papilledema (Fig. 52-22) were noted on neurologic examination. Brain imaging demonstrated diminished size of her lateral ventricles. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure was 350 mm CSF (normal < 180 mm CSF); it was otherwise normal.

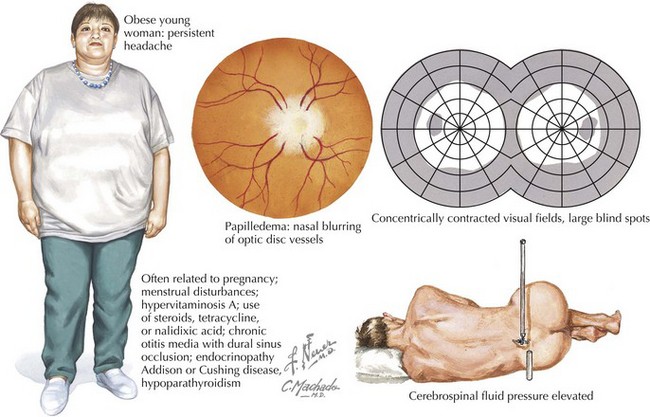

Intracranial Hypotension (Low-CSF-Pressure Syndrome)

Clinical Vignette

Classic low-CSF-pressure headaches are severe, exacerbated by postural factors, and often mimic the ball valve effect seen in some intraventricular brain tumors. Most commonly, these occur subsequent to a diagnostic lumbar puncture, spinal anesthesia, or a seemingly benign closed head injury. MRI with gadolinium is essential to the diagnosis (Fig. 52-23). When there is no history of a spinal tap or significant head trauma, this clinical setting, as well as the MRI, somewhat mimics various leptomeningeal neoplastic or inflammatory lesions. The MRI imaging with low pressure headache syndrome has a smooth enhancement in contrast to serpiginous irregular enhancement seen with neoplastic infiltration. The CSF analysis primarily helps make this differentiation. Occasionally introduction of a radioisotope into the CSF will identify a source of CSF leak that may require surgical repair. In many of these instances, no site of potential spinal fluid leak is identified. As in the above vignette, a spinal blood patch can provide relief and a therapeutic diagnosis; however, it is not universally successful and in rare instances the patient may have permanent incapacitation not being able to raise his/her head, preventing one from pursuing an occupation or even many routine activities of daily living.

Other Intracranial Lesions

Subdural hematomas, herpes encephalitis, brain abscess, and arteriovenous malformations may all have a clinical presentation similar to a brain tumor. There are other rare disorders both of demyelinating nature that require consideration in the differential diagnosis of brain tumors. Occasional patients have MRI findings mimicking a malignant glioma, but stereotactic biopsy demonstrates a primary monofocal acute inflammatory demyelination (see Chapter 46). These lesions usually are self-limited and occur in the setting where there is no prior clinical or MRI evidence of multiple sclerosis. Fortunately these are often responsive to corticosteroids. Subsequently, new lesions may appear in different portions of the cerebral cortex. An acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) and acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalopathy (AHL) are two acute postinfectious demyelinating disorders; the former is more likely to respond to corticosteroids and the latter frequently has a fulminate course (see Chapter 47).

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) may also present in a fashion similar to a brain tumor in immunocompromised hosts receiving long-term immunosuppressive therapy or in patients with HIV (see Chapter 51).

Ahsan H, Neugut AI, Bruce JN. Trends in incidence of primary malignant brain tumors in USA, 1981-1990. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24(6):1078-1085.

Berger MS, Hadjipanayis CG. Surgery of intrinsic cerebral tumors. Neurosurgery.. 2007 Jul;61(Suppl. 1):279-304.

Binder DK, Horton JC, Lawton MT, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:538-551.

Black PM. Meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:643-657.

Castrucci WA, Knisely JP. An update on the treatment of CNS metastases in small cell lung cancer. Cancer J. 2008 May-Jun;14(3):138-146.

Ciric I. Long-term management and outcome for pituitary tumors. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2003;14:167-171.

Daumas-Duport C, Scheithauer BW, O’Fallon J, et al. Grading of astrocytomas: a simple and reproducible method. Cancer. 1988;62:2152-2165.

Dietrich J, Norden AD, Wen PY. Emerging antiangiogenic treatments for gliomas—efficacy and safety issues. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008 Dec;21(6):736-744.

Gutrecht JA, Berger JR, Jones HR, et al. Monofocal acute inflammatory demyelination (MAID): a unique disorder simulating brain neoplasm. South Med J. 2002;95:1180-1186.

Karim AB, Afra D, Cornu P, et al. Randomized trial on the efficacy of radiotherapy for cerebral low-grade glioma in the adult: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Study 22845 with the Medical Research Council study BRO4: an interim analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52(2):316-324.

Kennedy PG. Viral encephalitis: causes, differential diagnosis, and management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(Suppl. 1):i10-i15.

Koss SA, Ulmer JL, Hacein-Bey L. Angiographic features of spontaneous intracranial hypotension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:704-706.

Larijani B, Bastanhagh MH, Pajouhi M, et al. Presentation and outcome of 93 cases of craniopharyngioma. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2004;13:11-15.

Maarouf M, Kuchta J, Miletic H, et al. Acute demyelination: diagnostic difficulties and the need for brain biopsy. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2003;145:961-969.

MacFarlane R, King TT. Acoustic neurinoma: vestibular schwannoma. In: Kaye AH, Larz ERJr, editors. Brain Tumors. Philadelphia, Pa: Churchill Livingstone; 1995:577-622.

Mason WP, Cairncross JG. Invited article: the expanding impact of molecular biology on the diagnosis and treatment of gliomas. Neurology. 2008 Jul 29;71(5):365-373.

Mathiesen T, Grane P, Lindgren L, et al. Third ventricle colloid cysts: a consecutive 12-year series. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:5-12.

Menezes AH, Gantz BJ, Traynelis VC, McCulloch TM. Cranial base chordomas. Clin Neurosurg. 1997;44:491-509.

Mokri B. Headaches caused by decreased intracranial pressure: diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:319-326.

Ohgaki H. Epidemiology of brain tumors. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:323-342.

Prados MD, Scott C, Curran WJJr, et al. Procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine (PCV) chemotherapy for anaplastic astrocytoma: A retrospective review of radiation therapy oncology group protocols comparing survival with carmustine or PCV adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1999 Nov;17(11):3389-3395.

Rapport RL, Hillier D, Scearce T, et al. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension from intradural thoracic disc herniation: case report. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(Suppl.):282-284.

Raschilas F, Wolff M, Delatour F, et al. Outcome of and prognostic factors for herpes simplex encephalitis in adult patients: results of a multicenter study. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:254-260.

Tentori L, Graziani G. Recent approaches to improve the antitumor efficacy of temozolomide. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(2):245-257.

Ullrich RT, Kracht LW, Jacobs AH. Neuroimaging in patients with gliomas. Semin Neurol. 2008;28(4):484-494.