Chapter 202 Botulism (Clostridium botulinum)

Pathogenesis

All forms of botulism produce disease through a final common pathway. Botulinum toxin is carried by the bloodstream to peripheral cholinergic synapses, where it binds irreversibly, blocking acetylcholine release and causing impaired neuromuscular and autonomic transmission. Infant botulism is an infectious disease that results from ingesting the spores of any of the 3 botulinum toxin-producing clostridial strains, with subsequent spore germination, multiplication, and production of botulinum toxin in the large intestine. Food-borne botulism is an intoxication that results when preformed botulinum toxin contained in an improperly preserved or inadequately cooked food is swallowed. Wound botulism results from spore germination and colonization of traumatized tissue by C. botulinum; it is the analog of tetanus. Inhalational botulism occurs when aerosolized botulinum toxin is inhaled. A bioterrorist attack could result in large or small outbreaks of inhalational or food-borne botulism (Chapter 704).

Clinical Manifestations

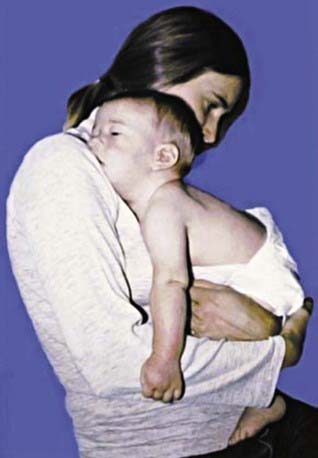

Botulinum toxin is distributed hematogenously. Because relative blood flow and density of innervation are greatest in the bulbar musculature, all forms of botulism manifest neurologically as a symmetric, descending, flaccid paralysis beginning with the cranial nerve musculature. It is not possible to have botulism without having multiple bulbar palsies, yet in infants, such symptoms as poor feeding, weak suck, feeble cry, drooling, and even obstructive apnea are often not recognized as bulbar in origin (Fig. 202-1). Patients with evolving illness may already have generalized weakness and hypotonia in addition to bulbar palsies when first examined. In contrast to botulism caused by C. botulinum, a majority of the rare cases caused by intestinal colonization with C. butyricum are associated with a Meckel diverticulum accompanying abdominal distention, often leading to misdiagnosis as an acute abdomen. The also rare C. baratii type F infant botulism cases have been characterized by very young age at onset, rapidity of onset, and greater severity of paralysis.

Diagnosis

Infant botulism requires a high index of suspicion for early diagnosis (Table 202-1). “Rule out sepsis” remains the most common admission diagnosis. If a previously healthy infant (commonly 2-4 mo of age) demonstrates weakness with difficulty in sucking, swallowing, crying, or breathing, infant botulism should be considered a likely diagnosis. A careful cranial nerve examination is then very helpful.

Table 202-1 DIAGNOSES CONSIDERED IN SUBSEQUENTLY LABORATORY-CONFIRMED CASES OF INFANT BOTULISM

| ADMISSION DIAGNOSIS | SUBSEQUENTLY CONSIDERED DIAGNOSES |

|---|---|

| Suspected sepsis, meningitis | Guillain-Barré syndrome |

| Pneumonia | Myasthenia gravis |

| Dehydration | Disorders of amino acid metabolism |

| Viral syndrome | Hypothyroidism |

| Hypotonia of unknown etiology | Drug ingestion Organophosphate poisoning |

| Constipation | Brainstem encephalitis |

| Failure to thrive | Heavy metal poisoning (Pb, Mg, As) |

| Spinal muscular atrophy (Werdnig-Hoffmann disease) | Poliomyelitis Viral polyneuritis Hirschsprung disease Metabolic encephalopathy Medium chain acetyl–CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency |

Differential Diagnosis

Botulism is frequently misdiagnosed, most often as a polyradiculoneuropathy (Guillain-Barré or Miller Fisher syndrome), myasthenia gravis, or a disease of the central nervous system (Tables 202-1 and 202-2). In the USA, botulism is more likely than Guillain-Barré syndrome, intoxication, or poliomyelitis to cause a cluster of cases of acute flaccid paralysis. Botulism differs from other flaccid paralyses in its prominent cranial nerve palsies disproportionate to milder weakness and hypotonia below the neck, in its symmetry, and in its absence of sensory nerve damage. Spinal muscular atrophy may closely mimic infant botulism at presentation.

Treatment

Human botulism immune globulin, given intravenously (BIG-IV), is licensed for the treatment of infant botulism caused by type A or B botulinum toxin. Treatment with BIG-IV consists of a single intravenous infusion of 50-100 mg/kg (see package insert) that should be given as soon as possible after infant botulism is suspected in order to immediately end the toxemia that is the cause of the illness. Treatment should not be delayed for laboratory confirmation. In the USA, BIG-IV may be obtained from the California Department of Health Services (24-hr telephone 510-231-7600; www.infantbotulism.org). The use of BIG-IV shortens mean hospital stay from ≈6 wks to 2 wks. Most of the decrease in length of hospital stay results from the reduced time that the patient requires ventilation and in intensive care. Hospital costs are reduced by >$100,000 per case (in 2004 dollars).

Antibiotic therapy is not part of the treatment of uncomplicated infant or food-borne botulism, because the toxin is primarily an intracellular molecule that is released into the intestinal lumen with vegetative bacterial cell death and lysis. Antibiotics are reserved for the treatment of secondary infections, and in the absence of antitoxin therapy, a nonclostridiocidal antibiotic such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is preferred. Aminoglycoside antibiotics should be avoided because they may potentiate the blocking action of botulinum toxin at the neuromuscular junction. Wound botulism requires aggressive treatment with antibiotics and antitoxin in a manner analogous to that for tetanus (Chapter 203).

Complications

Almost all of the complications of botulism are nosocomial, and a few are iatrogenic (Table 202-3). Some critically ill, pharmacologically paralyzed patients who must spend weeks or months on ventilators in intensive care units inevitably experience some of these complications. Suspected “relapses” of infant botulism usually reflect premature hospital discharge or an inapparent underlying complication such as pneumonia, urinary tract infection, or otitis media.

Arnon SS, Schechter R, Maslanka SE, et al. Human botulism immune globulin for the treatment of infant botulism. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:462-471.

Barash JR, Hsia JK, Arnon SS. Presence of soil-dwelling clostridia in commercial powdered infant formulas. J Pediatr. 2010;156:402-408.

Chertow DS, Tan ET, Maslanka SE, et al. Botulism in 4 adults following cosmetic injections with an unlicensed, highly concentrated botulinum preparation. JAMA. 2006;296:2476-2479.

Fernicia L, Anniballi F, Aurelia P. Intestinal toxemia botulism in Italy, 1984–2005. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26:385-394.

Francisco AMO, Arnon SS. Clinical mimics of infant botulism. Pediatrics. 2007;119:826-828.

Gottlieb SL, Kretsinger K, Tarkhashvili N, et al. Long-term outcomes of 217 botulism cases in the Republic of Georgia. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:174-180.

Koepke R, Sobel J, Arnon SS. Global occurrence of infant botulism, 1976–2006. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e73-e82.

Long SS. Infant botulism and treatment with BIG-IV (BabyBIG). Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:261-262.

Mitchell WG, Tseng-Ong L. Catastrophic presentation of infant botulism may obscure or delay diagnosis. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e436-e438.

Nevas M, Lindstrom M, Virtanen A, et al. Infant botulism acquired from household dust presenting as sudden infant death syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:511-513.

Sobel J. Botulism. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1167-1173.

Underwood K, Rubin S, Deakers T, et al. Infant botulism: a 30-year experience spanning the introduction of botulism immune globulin intravenous in the intensive care unit at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1380-e1385.