CHAPTER 71 Botox® for face, neck and brow

History

Clostridium botulinum bacterium was first recognized and isolated in 1896 by Emile van Ermengem. In 1944, Edward Schantz successfully cultured Clostridium botulinum and was able to isolate the potent toxin. In 1949, Burgen’s group discovered that botulinum toxin blocks neuromuscular transmission. C. botulinum bacteria produce eight serologically distinct types of botulinum neurotoxins designated as type A, B, C1, C2, D, E, F and G. Type A seems to be the most potent in humans. During the 1950s, Dr Vernon Brooks started experimenting with botulinum toxins for medical purposes. His work was later significantly advanced by the works of Dr Alan Scott during the 1970s. In 1977, botulinum neurotoxins were used in humans for the first time. Botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A) was granted limited approval by the FDA for the treatment of strabismus in 1979. The approval was later extended to blepharospasm in 1985. The FDA approved the use of Botox® botulinum toxin type A (Allergan Inc., Irvine, CA USA) for these two conditions and for the treatment of hemifacial spasm in 1989. On April 15 2002 Botox® Cosmetic was granted FDA approval for the treatment of moderate to severe glabellar rhytides by extensive clinical trials following observations on the cosmetic effectiveness on glabellar frown lines by Drs Jean and Alastair Carruthers made in 1987 while treating a patient with blepharospasm.1

As a commercially available unique pharmaceutical agent, Botox® popularity continues to grow and expand into other therapeutic applications as well as cosmetic improvement of a wide range of facial wrinkles in addition to those for which it was initially approved.2 Since its discovery as a wrinkle reducer, Botox® is the leading male and female minimally-invasive cosmetic procedure in the U.S. with more than 4.6 million treatments performed in 2007 alone, a remarkable 488% increase since the year 2000.3

This neurotoxin acts by inhibiting the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction of striated muscle fibers. This inhibition produces selective chemical reversible denervation of the muscle and as a result muscle activity is temporarily diminished. The toxin does not damage the nerves or alter the production of acetylcholine.4 Botox® weakens muscle action in approximately 2 to 4 days following injection and reaches maximal muscle denervation between 7 to 10 days. The effect is temporary since the terminal nerve endings start to form “peripheral sprouts” with time.

Following the appropriate dose and injected on the target muscles, botulinum toxin can temporarily address some of these senescent changes of the facial skin. It is the experience of these authors that with repeated treatment some degree of muscle atrophy may occur; therefore, subsequent treatments might require fewer units of toxin at longer time intervals. However, resistance has been seen in patients treated for neurologic conditions where doses are in the 100–200 units (U) range5 and it is currently a concern that cosmetic patients might develop neutralizing antibodies with repeated treatment.

Physical evaluation

• Obtain a complete medical history.

• Obtain a complete list of concomitant medications.

• Evaluate for history of muscular disorders.

• Evaluate for any signs of skin infection or inflammation.

• Evaluate for any disorder affecting the eyes.

• Evaluate for unequal eyebrow height.

• Obtain list of past cosmetic procedures including fillers and Botox® history.

• Botox® treatment is contraindicated during pregnancy, breastfeeding or patients planning to become pregnant.

Technical steps

Treatment of the upper face

Botox® Cosmetic has been proven to be a safe and effective modality for treating wrinkles of the upper face. This area has provided the majority of clinical experiences with Botox®. Glabellar frown lines, horizontal forehead lines and crow’s feet are the most common manifestation of the aging upper face. With the success of Botox® treatment in the upper face, clinicians have been expanding this therapy into other areas of the face.6 However, Botox® is only approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of glabellar frown lines.

Glabellar frown lines

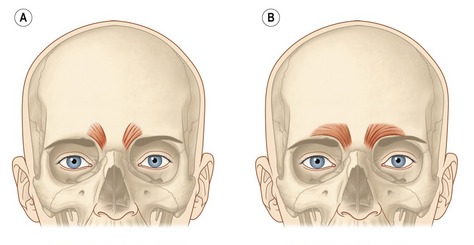

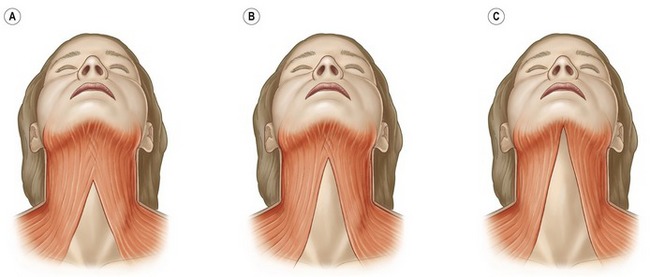

The underlying muscular activity of the procerus, corrugator supercilli and depressor supercilli muscles is responsible for the formation of the glabellar frown lines. The synergetic hyperactivity of these muscles produces the usually undesired facial appearance of age, fatigue and frustration. The procerus is a thin, narrow brow depressor muscle. Once contracted, it draws the medial aspect of the eyebrows down, producing transverse wrinkles over the nasal bridge. This muscle should be injected in the midline, slightly caudal to the root of the nose. The contraction of the corrugator supercilli muscle adducts and depresses the eyebrow, moving it inferiorly and medially. Repetitive contraction of the corrugator supercilli muscles produces the vertical glabellar creases. There are two well distinct patterns of this muscle. It can have a short, pyramidal shape located at the medial end of the supraorbital ridge (Fig. 71.1A) or a long and narrow shape extending along the supraorbital ridge reaching or even going beyond the mid-brow (Fig. 71.1B). Treatment of this muscle with Botox® should follow the respective anatomical pattern of the muscle. The depressor supercilli is a brow depressor and believed to be part of the orbicularis oculi muscle. The appropriate knowledge of the existence of this muscle allows for proper inactivation with Botox® injections. Several factors of the glabellar complex should be observed prior to treatment. Physical characteristics, such as brow arch, brow asymmetry, brow ptosis and muscle mass of the glabellar varies between male and females. Males tend to have a stronger muscle mass; therefore, higher doses in the range of 60 to 80 U of Botox® are often necessary to achieve the desired effect. Doses in the range of 30 to 40 U are usually sufficient to produce a satisfactory result on females. Injection techniques vary by clinicians. The following injection technique is used by the authors’ clinic:

• Following sterile technique and having the patient positioned with the chin down and head slightly lower that clinicians’, inject the procerus with 5–10 U mid-line and at a point below a line joining the brows.

• Next inject the center of the corrugator with 5 U above the caruncle of the inner canthus. Always inject above the bony supraorbital ridge. It is recommended that injectors maintain their non-dominant thumb on the orbital rim to avoid injection within the orbit.

• Then inject 5 U at 1 cm above the previous injection site and 3–5 U into a point 1 cm above the supraorbital rim in the mid-pupillary line. Repeat injections on the contralateral side to achieve a balanced outcome (Fig. 71.2).

Horizontal forehead lines

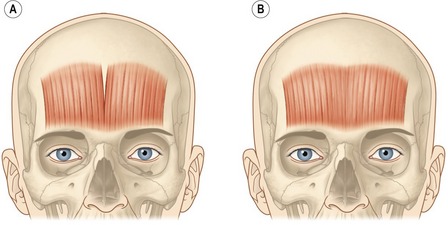

The frontalis muscle main function is to elevate the eyebrows. This muscle can have two clinical functional patterns. The most common shape of the frontalis is by a single continuous broad band (Fig. 71.3A). With chronic brow elevation this pattern produces contiguous transverse forehead lines. The second pattern, not very often seen clinically, has two broad bands with a central separation producing a smooth mid-section with a corrugated lateral forehead when the frontalis elevates the brow (Fig. 71.3B). Treatment of the forehead horizontal lines should be done with caution and only after the glabellar complex has been successfully treated and there is no presence of brow ptosis due to compensatory response by the overactive use of the frontalis. Over-weakening of the frontalis muscle will exacerbate brow ptosis and might yield a lowered brow producing an undesired angry and aggressive expression on patients with normal brow position. This can be avoided if the corresponding depressors are also properly treated. After careful evaluations of the brow height, a conservative approach must be utilized in order to slightly weaken the frontalis muscle action with small doses ranging from 2 to 3 U injected at 1.5 cm intervals in five evenly distributed points. The injection sites must be maintained well above the brow (Fig. 71.4). Patients with low-sitting foreheads and droopy upper eyelids are poor candidates for treatment of forehead rhytides because their eyelids may descend to the point of obstruction of their vision, if the frontalis muscle is treated. In contrast, injections into the brow depressors may be very effective for these patients.

Brow elevation

Brow shape, height and position are determined by a delicate interaction between depressor and elevator muscles. Brow configuration varies from patient to patient. The muscles responsible for brow movement are the frontalis (brow elevator), procerus, orbicularis oculi and corrugator supercilli (brow depressors). Botox® injections have the potential benefit of producing a brow lift if injected properly. Botox® can be used to shape the brow for a more aesthetically pleasing eyebrow on female patients as well as to treat brow asymmetry. Many clinicians have observed that treating the glabellar complex alone as described above can have an effect on brow elevation. It has been suggested that this is the result of diffusion of BTX-A into the medial fibers of the frontalis which causes partial inactivation and an increased resting tone of this muscle.7 In addition Botox® can be injected into specific points of the orbicularis oculi muscle to produce a lateral brow lift which widens the eye leading to a more youthful appearance.8 This requires a single lateral injection with 1–2 U of Botox® into the tail of each eyebrow approximately 1.5 cm from the orbital rim (Fig. 71.5).

Crow’s feet

Wrinkles radiating from the lateral canthal region usually in fan-shaped distribution are referred to as crow’s feet. These lines are caused by the contraction of the orbicularis oculi and occasionally in some patients by contraction of the zygomaticus major. Careful examination of the patient’s crow’s feet should be done previous to overall treatment since in some patients, crow’s feet are distributed equally above and below the lateral canthus. In some patients, crow’s feet develop mainly below the lateral canthus. Botox® injections dramatically reduce the appearance of crow’s feet rhytides by temporarily weakening the lateral orbicularis oculi muscle on patients with mild to moderate deep lateral canthal rhytides. Typically, three injection sites are treated with 2–5 U of Botox® each into the lateral orbital rim as determined while the patient is smiling maximally. It is important that the injections are performed when the patient is not smiling since this can cause diffusion of the toxin into the ipsilateral zygomaticus complex, causing ptosis of the upper lip. Always inject above the zygomatic arch. The first injection should be in the center of the area of maximal wrinkling. The second and third injection sites are approximately 1 to 1.5 cm above and below the first injection site, respectively. In addition to the three injection sites, 2 to 4 U are injected into the inferior orbicularis oculi below the mid pupillary line to widen the eye (Fig. 71.5). It is important to remember that a snap test should always be performed before injecting the lower eyelids with botulinum toxin to test for the retraction of the skin, as patients with a delayed retraction of the lower eyelid may experience ectropion of the injected eye when the periocular muscles are rendered inactive by the toxin. Ecchymoses is common when treating this area so ice compresses are recommended after each side is treated.

Treatment of the midface and lower face

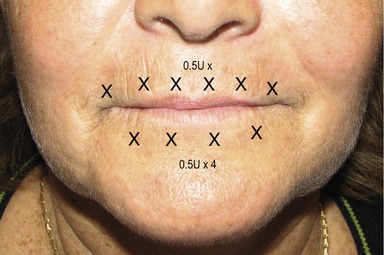

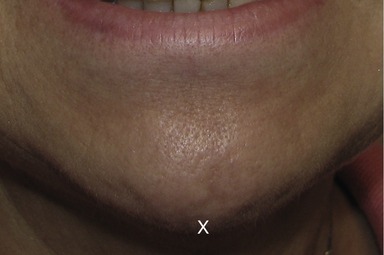

To ameliorate perioral fine rhytides, the superficial fibers of the orbicularis oris are injected with 0.5–1 U at six points 2–3 mm above the vermillion border. The same technique can be applied to the lower lip; however, on four points only (Fig. 71.6). The depressor anguli oris muscles are injected at the most inferior portion with 2–4 U placed on either side on an imaginary line drawn as a continuation of the nasolabial fold to elevate the corner of the mouth. This is usually done at about 1 cm above the intersection of this line and the angle of the jaw (Fig. 71.7). Many patients realize that the texture of their chin changes with various expressions. An injection of 5–10 U of botulinum toxin into the inferior portion of the mid chin (mentalis muscle) helps in smoothing out the dimpling of the chin (Fig. 71.8). Care should be taken to avoid injecting the depressor labii inferioris.9

Treatment of the neck

The complete understanding of the anatomical complexity of the lower face is an essential factor for an effective treatment outcome. The procedure described here is for experienced physicians who are very familiar with the agonist-antagonist muscles and dynamic contraction force vectors that compromise the lower face and neck. The clinicians must understand that the BTX-A dosing for the neck area differs from the upper face and the importance of placement and injection technique cannot be further emphasized for safety and optimal results.

Overlapping the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the platysma is a superficial flat and broad muscle generally considered as the inferior most portion of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS). The muscle originates inferiorly as two independent sheets from the upper chest connecting to the fascia overlying the pectoralis major and deltoid muscles. The muscle approaches anteriomedially with fibers eventually blending with the masseter, depressor anguli oris, mentalis, risorius and orbicularis oris. These medial fibers of the platysma exhibit considerable anatomical and thickness variations and are responsible for the aging appearance of the neck. There are three main variants of the platysma muscle which are categorized as type I, II and III (Fig. 71.9). Approximately 75% of patients have the type I variant where the medial fibers are separated approximately at a 1–2 cm level of the submental region. Fifteen percent of patients present the type II variant where the entire submental region is covered with the platysma muscle and the muscle decussation is at the level of the thyroid cartilage. Type III occurs in fewer than 10% of patients where there is no decussation of the platysma muscle resulting in the two muscles running independently.

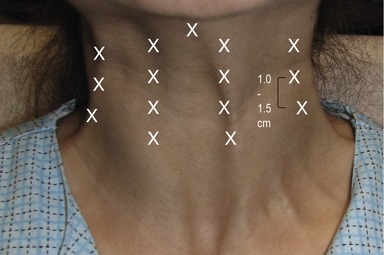

The hyperfunctional platysma bands may be effectively treated with Botox®. No anesthesia is required for this procedure. In order to better visualize the platysma bands, the patient is asked to contract their anterior neck by strongly clenching their teeth and depressing the lateral oral commissures. This facial expression exacerbates the platysma bands. Using the non-dominant hand, the clinician then grasps each band between the thumb and index finger (Fig. 71.10). Each band is injected with a 30-gauge needle three to four times at intervals of 1–1.5 cm apart with 3–10 U from the jawline to the lower neck (Fig. 71.11). Thinner bands will require a total of 15–20 U, while thicker bands may require up to 30 U. It is not unusual to inject the platysmal muscle with 150 U. However, it is important to understand that with higher doses, adverse events such as sternomastoid weakness and dysphagia increases. With experience, the injecting clinician will learn to identify the resistance of the platysma bands and tailor the appropriate BTX-A dosage. Intradermal injections of the horizontal neck rhytides, commonly referred to as necklace lines, with 1–2 U at 1 cm intervals also effectively ameliorate the appearance of these fine lines.

Complications

The majority of complications from Botox® injections are temporary and subside in a few weeks. The main general adverse events are bruising, pain, tenderness, slight erythema, swelling and inflammation resulting from piercing the skin when injecting the neurotoxin. It is recommended to use ice therapy to minimize pain and bruising during injections. It is important to reassure the patients that these mild complications are not caused by the toxin itself. Systemic complications are extremely rare. There have not been reports of serious systemic adverse events with the use of Botox® Cosmetic to treat facial aging. The most common regional complications for the upper face are brow ptosis, brow asymmetry, quizzical appearance, eyelid drop and lack of facial expression. Lower eyelid atrophy, ecchymoses, dry eye, diplopia, lid ptosis, dysgeusia and brow ptosis are the most common adverse events that might occur in the periocular region. These can be prevented with proper injection technique. Aproclonidine 0.5% (Lopidine, Alcon Labs Fort Worth, TX), naphazoline (Alcon Labs) and phenylephrine 2.5% (Myfrin, Alcon Labs) eye drops can be used in case of lid ptosis.10

Botox® therapy for the mid and lower face is only recommended for experienced clinicians. Lip drop, mouth ptosis and asymmetric smile are temporary adverse events commonly encountered when too much toxin is injected into this area. The perioral area must be injected very superficially to prevent lip inversion and/or eversion, lip ptosis, drooling and to prevent oral incompetence which might affect pronunciation. The most common complications of the lower face are the result of injecting inadequate dosages or the wrong muscles. Knowledge of the intricate musculature of the lower face is crucial. Along with the usual discomfort associated with injecting the platysmal muscle, other adverse effects are neck weakness, neck discomfort, muscle soreness, difficulty lifting the head from a decubital position and minor headaches. Most reported serious side effects are technique dependent such as injecting too much toxin, injecting too deeply, or with too much pressure, producing hoarseness and dysphagia.11,12 Treatment of the lower face must be performed by experienced professionals only.

1. Carruthers A, Carruthers J. The cosmetic use of botulinum neurotoxin, 1st edn. Marcel New York: Dekker; 2001.

2. Fagien S, Brandt FS. Primary and adjunctive use of botulinum toxin type A (Botox) in facial aesthetic surgery: beyond the glabella. Clin Plast Surg. 2001;28(1):127–148. Review

3. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. 2008 Report of the 2007 statistics. National Clearinghouse of Plastic Surgery Statistics. www.plasticsurgery.org. (Accessed 30 May 2008)

4. Lowe NJ. Overview of botulinum neurotoxins. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2007;9(suppl 1):11–16.

5. Dressler D, Hallett M. Immunological aspects of Botox, Dysport and Myobloc/Neurobloc. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13(suppl 1):11–15.

6. Flynn TC. Update on botulinum toxin. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26(4):196–202.

7. Carruthers A, Carruthers J. Eyebrow height after botulinum toxin type A to the glabella. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33(1):S26–31.

8. Flynn TC, Carruthers J, Carruthers A. Botulinum A toxin treatment of the lower eyelid improves infraorbital rhytids and widens the eye. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:703–708.

9. Finn JC, Cos SE, Practical Botulinum toxin anatomy, Chapter 3, Botulinum toxin. Carruthers A, Carruthers J. Procedures in cosmetic dermatology, 2nd edn, London: Saunders Elsevier, 2008.

10. Vartanian AJ, Dayan SH. Complications of botulinum toxin A use in facial rejuvenation. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am. 2005;13:1–10.

11. Brandt F, Boker A, Moody BR, Cazzaniga A, Neck treatment, Chapter 3, Botulinum toxin. Carruthers A, Carruthers J. Procedures in cosmetic dermatology, 2nd edn. Saunders Elsevier, London, 2008:65–72.

12. Brandt FS, Cazzaniga A. complications of Botulinum toxin. In: Keyvan N, ed. Complications in dermatologic surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2008:257–265.