8 Bone tumours and other local conditions

TUMOURS OF BONE

Primary bone tumours, both benign and malignant, are relatively uncommon in comparison with the malignancies arising in other tissues of the body. They are also much less common than metastatic (secondary) tumours which affect the skeleton by blood stream spread from primary carcinoma of the breast, prostate, lung or kidney.

The importance of primary bone tumours is not their frequent occurrence, but the difficulty they may present in diagnosis and treatment and the need to distinguish them from a number of tumour-like lesions that affect bone. Tumours originating in bone arise from mesenchymal tissue and if malignant are termed sarcoma. They are normally classified by the predominant cell type in the lesion, which may be bone, cartilage or fibrous tissue (Table 8.1).

| Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|

| Arising from bone | |

| Osteoma | Osteosarcoma |

| Osteoid osteoma | |

| Osteoblastoma | |

| Giant-cell tumour | |

| Arising from cartilage | |

| Enchondroma | Chondrosarcoma |

| Osteochondroma (cartilage capped exostosis) | |

| Chondromyxoid fibroma | |

| Chondroblastoma | |

| Arising from fibrous tissue | |

| Fibrous cortical defect | Malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) |

| Non-ossifying fibroma | |

| Fibrous dysplasia | |

| Tumours of uncertain origin | |

| Simple bone cyst | Ewing’s sarcoma |

| Aneursymal bone cyst | Adamantinoma |

Margin of the lesion. Slow-growing tumours have well-defined sometimes sclerotic margins and are most likely benign. Rapidly growing lesions will have ill-defined margins and appear to permeate diffusely into the surrounding bone. While this typically indicates a malignant process, other rapidly progressing conditions, such as acute osteomyelitis, can give a similar appearance.

Breach of cortex. Destruction of the cortex indicates an aggressive invasive lesion.

Biopsy. In the majority of cases it is necessary to undertake a biopsy of material from the lesion for histological and bacteriological examination to reach a final definitive diagnosis. The biopsy may be an open procedure, or a closed needle or trephine technique may be used. The closed technique may be guided by CT scanning, but gives very little material for additional investigations, such as immunohistochemistry or cytogenetics. Needle biopsy should only be used where advice is available from an expert bone pathologist with the necessary technical resources for processing small tissue samples. Once diagnosed the treatment of the lesion depends on whether it is benign or malignant and will be described in more detail for the individual types of tumour.

BENIGN TUMOURS OF BONE

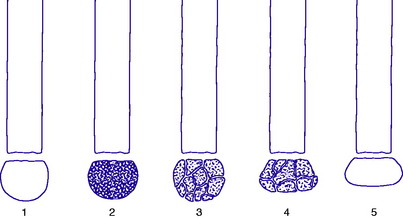

Fig. 8.2 Two types of chondroma: ecchondroma on proximal phalanx; enchondroma in middle phalanx. (See also Figs 6.4A, B)

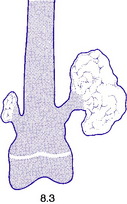

Fig. 8.3 A small and a large osteochondroma. Originating at the growth cartilage, they have migrated away from it with growth of the bone. Each is capped by cartilage. (See also Fig. 6.3B)

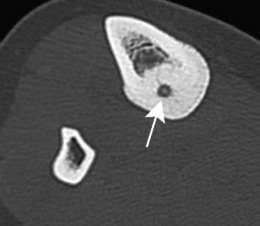

Osteoid osteoma

This is a benign circumscribed lesion that may arise in the cortex of long bones or occasionally in the cancellous bone of the spine. It affects young patients aged 10–35 and is three-times commoner in males.

Pathology. The characteristic feature is the formation of a small nidus of osteoid tissue, usually less than 0.5 cm diameter, surrounded by a reactive zone of dense sclerotic new bone formation (Fig. 8.1).

Imaging. Plain radiographs typically show local sclerotic thickening of the shaft that may obscure the small central nidus within the area of rarefaction (Fig. 8.5). The nidus is best seen on a fine cut CT scan (Fig. 8.6) and also exhibits intense uptake on an isotope bone scan.

Chondroma

Pathology. There are two forms of chondroma: in the commonest type the tumour grows within a bone and expands it (enchondroma) (Fig. 8.2); in the other more rare form it grows outward from a bone (periosteal chondroma or ecchondroma). Most periosteal chondromas arise in the hands or feet, or from flat bones such as the scapula or ilium. They often reach a large size and are more prone to develop malignant change. Enchondromas are fairly common in the long bones, but over 50% occur in the small bones of the hands and feet. The affected bone is expanded by the tumour and its cortex is much thinned; so pathological fracture is common and usually the presenting feature. Many remain asymptomatic and are only discovered as chance findings on radiographs taken for other purposes.

Imaging. Central enchondromas expand the bone with thinning, but not erosion, of the cortex and exhibit a variable degree of mineralisation or speckled calcification (Fig. 8.7).

Multiple enchondromata of the major long bones occur mainly in the distinct, but rare, clinical condition known as dyschondroplasia (multiple chondromatosis or Ollier’s disease) (p. 65). In this disorder, which begins in childhood, enchondromata arise in the region of the growing epiphysial cartilages (growth plates) of several bones: they interfere with normal growth at the epiphysial plate and consequently may lead to shortening or deformity (see Fig. 6.4A).

Osteochondroma (osteocartilaginous exostosis)

This is the commonest benign tumour of bone, usually presenting in the 10–20 age group.

Pathology. The tumour originates in childhood from the growing epiphysial cartilage plate, but as the bone grows in length the outgrowth gets ‘left behind’ and tends to point away from the adjacent joint. It frequently grows outwards from the bone like a mushroom with a bony stalk in continuity with the cortex of the underlying bone (Fig. 8.3). Less commonly the lesion may be sessile with a more broad-based origin. The bony stalk has a larger cap of cartilage which continues to grow until the cessation of skeletal growth.

The ordinary osteochondroma is single; but in the condition known as diaphysial aclasis (multiple exostoses) (p. 63) the tumours affect several or many bones. The risk of malignant change to a chondrosarcoma is higher in these multiple lesions than in the solitary lesion and should be suspected if the tumour continues to enlarge or becomes painful after puberty.

Imaging. Plain radiographs show the mushroom-like stalk of the bony tumour (Fig. 8.8), but not the larger cartilaginous cap until this calcifies once skeletal maturity is reached. Patients with known lesions should be warned to seek referral for further imaging if their swelling enlarges or becomes painful.

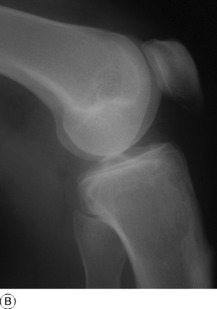

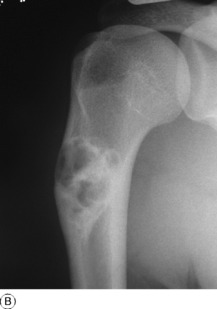

Giant-cell tumour (osteoclastoma)

Pathology. The commonest sites are the lower end of the femur, the upper end of the tibia, the lower end of the radius, and the upper end of the humerus – that is, at those ends of the long bones at which most growth occurs. It may also occur in the spine and sacrum. Characteristically it occurs in the end of the bone, occupying the epiphysial region and often extending almost to the joint surface (Fig. 8.4). It destroys the bone substance, but new bone forms beneath the raised periosteum, so that the bone end becomes expanded and pathological fracture is common.

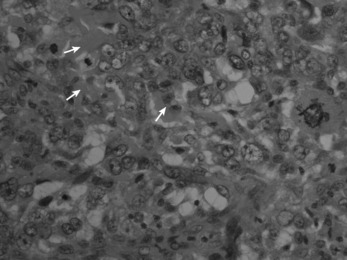

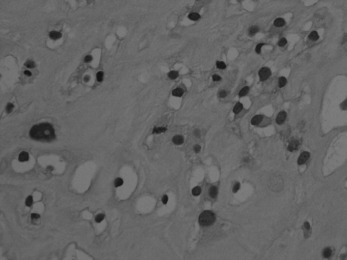

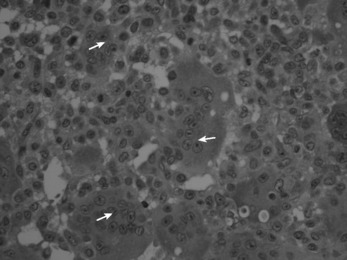

Histologically the tumour consists of abundant mononuclear oval or spindle-shaped stromal cells profusely interspersed with giant cells that may contain as many as fifty nuclei (Fig. 8.9), hence the name ‘giant cell tumour’. The giant cells possibly represent fused conglomerations of the oval or spindle-shaped stromal cells, which may frequently show mitotic figures, though this is not necessarily indicative of malignant change.

Fig. 8.9 Histology of giant cell tumour showing large osteoclastic multinucleate giant cells (arrows) with interspersed mononuclear tumour cells. The nuclei of the two cell types are very similar. (Haematoxylin and eosin ×400.)

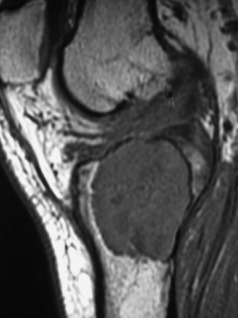

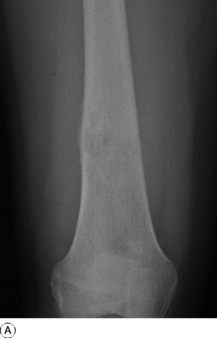

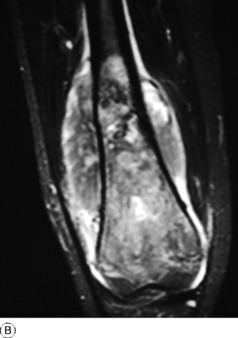

Imaging. Radiographs show lytic destruction of the bone substance, with expansion of the cortex, but no sclerotic rim or periosteal reaction (Fig. 8.10). A few bony trabeculae may remain within the tumour giving a faintly loculated appearance. The tumour tends to grow eccentrically, and often extends as far as the articular surface of the bone. Magnetic resonance imaging will help to determine the amount of soft tissue extension of the tumour (Fig. 8.11).

Treatment. This depends upon the site of the tumour. Curettage of the contents with a high-speed burr is the standard method of treatment for most giant cell tumours, though this is associated with a high rate (20–25%) of recurrence. This rate can be reduced to less than 10% by the use of adjuvant treatment applied to the lining of the cavity after curettage. Methods used include the chemical phenol, freezing with liquid nitrogen, or the insertion of polymethylmethacrylate bone cement. In addition to its exothermic reaction on any residual cells, the cement has the added advantage of providing support to the subchondral bone and cartilage of the articular surface of the joint. In some bones, or after multiple recurrences, it may be possible to excise the tumour and replace it with allograft bone or a metal prosthesis, without undue functional compromise. Sites where this is possible include the distal radius, distal femur, and proximal tibia.

MALIGNANT TUMOURS OF BONE

Osteosarcoma (osteogenic sarcoma)

This is predominantly a tumour of childhood or adolescence, occurring most commonly in the 10–25 age group. When it occurs in later life it is often a complication of Paget’s disease (osteitis deformans) (p. 66).

Pathology. An osteosarcoma arises from primitive bone-forming cells. The commonest sites are the lower end of the femur, the upper end of the tibia, and the upper end of the humerus – that is, in those areas in which, prior to epiphysial fusion, most active growth is occurring. The tumour begins in the metaphysis – that is, the part of the shaft that is adjacent to the epiphysial plate. It destroys the bone structure and eventually bursts into the surrounding soft tissues, though it seldom crosses the epiphysial cartilage into the epiphysis itself (Fig. 8.12). The histological appearance varies widely, because any type of connective tissue may be represented. Thus the tumour may be composed largely of fibrous tissue, of cartilage or of myxomatous tissue; but characteristically there will always be found, in some parts of the tumour, areas of neoplastic new bone or osteoid tissue that indicate the true nature of the lesion, and in some cases newly formed bone is abundant (Fig. 8.16). The tumour metastasises early by the blood stream, especially to the lungs and sometimes to other bones.

Imaging. Plain radiographs show irregular medullary and cortical destruction of the metaphysis. Later the cortex appears to have been ‘burst open’ at one or more places by the soft tissue extension (Fig. 8.17), but there are always vestiges of the original cortex. MR scanning allows accurate delineation of the tumour size and the extent of invasion of the soft tissues (Fig. 8.18). There is usually evidence of new bone formation under the corners of the aggressive periosteal reaction (Codman’s triangle) (Fig. 8.17B). Occasionally well-marked radiating spicules of new bone are seen within the tumour (‘sun-ray’ appearance) (Fig. 8.17A). In a parosteal osteosarcoma, a variant that may occur in older patients with a better prognosis, there may be profuse formation of new bone on the surface of the cortex.

Fig. 8.18 A Radiograph of osteosarcoma of the femur. There is an area of ill-defined lucency in the mid shaft associated with some periosteal reaction. B MR of same patient. The area of marrow abnormality is seen to be extending far into the distal femur with a large soft tissue mass surrounding the femur not evident on the plain film.

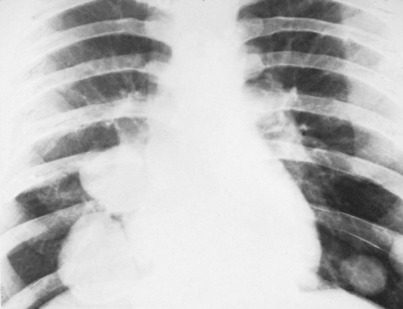

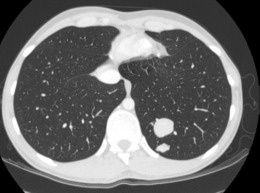

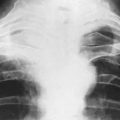

A chest radiograph may show pulmonary metastases (Fig. 8.19), but CT scanning of the lung fields (Fig. 8.20) is now mandatory for pre-treatment staging as it can detect small pulmonary metastases before they are apparent in plain radiographs.

Diagnosis. In atypical cases an osteosarcoma may be confused with subacute osteomyelitis, or with other bone tumours such as chondrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, giant-cell tumour, Ewing’s tumour, or even metastatic tumour. A representative piece of the tumour should always be removed by closed needle or open biopsy and sent for histological examination.

Treatment. The introduction of new powerful cytotoxic drugs for adjuvant chemotherapy has revolutionised the treatment of these tumours, because of their ability to prevent or delay the appearance of pulmonary micrometastases. The drugs currently used include high-dose methotrexate, doxorubicin, cisplatin, and ifosfamide in combinations which are the subject of multi-centre controlled trials. They all have major side effects and should only be used at treatment centres skilled in their use. Chemotherapy is usually commenced before surgical treatment, and is continued intermittently for 6 months to a year after ablation of the tumour. Commencing chemotherapy before operative treatment allows the pathologist to assess the response of the tumour to the drugs by histological examination of the resected specimen. The ability of chemotherapy to control local recurrence and distant metastatic spread has permitted the increasing use of ‘limb salvage surgery’ as an alternative to amputation. In selected cases, based on accurate surgical staging from biopsy and modern imaging techniques, it is possible to undertake radical resection and replacement with a metallic prosthesis or a massive bone graft. Recent reports have shown over 70% disease-free survival after 5 years by this approach in patients with osteosarcoma, with no increase in local recurrence rates when compared with amputation.

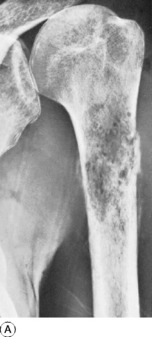

Chondrosarcoma of bone

Pathology. It may develop in the interior of the bone (central chondrosarcoma) or upon its surface (peripheral chondrosarcoma). A central chondrosarcoma occurs most commonly in the femur, the tibia, or the humerus. It may arise de novo, without there having been a pre-existing lesion (Figs 8.21 and 8.22), or it may arise from malignant transformation of a previously existing enchondroma (especially in the condition known as dyschondroplasia, Ollier’s disease or multiple chondromatosis (p. 65).

Fig. 8.21 Radiograph of proximal femur with a central chondrosarcoma. The lytic lesion has produced endosteal scalloping, indicating an aggressive lesion, and shows calcification indicating a chondroid matrix.

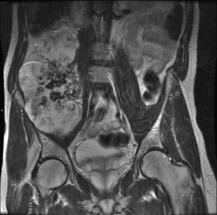

A peripheral chondrosarcoma, on the other hand, tends usually to affect a flat bone such as the innominate bone (Figs 8.23 and 8.24), the sacrum, or thescapula, and it generally arises from malignant transformation of a previously existing osteochondroma (especially in the condition of diaphysial aclasis or multiple exostoses (p. 63)).

Fig. 8.24 MR of same patient as in Fig. 8.23 shows a much larger mass than is apparent on the plain film. This consists of non-calcified cartilage and suggests that the chondrosarcoma has developed in a cartilage-capped exostosis arising from the pelvis.

Histologically, a chondrosarcoma may be highly cellular (Fig. 8.25). The cartilage cell nuclei tend to be swollen, and double nuclei may be seen. These features, suggestive of malignancy, may be found in only a few microscopic fields, the remainder of the tissue appearing relatively benign.

Imaging. Radiographically, a central chondrosarcoma is seen to grow at the expense of the cortical bone with endosteal scalloping and may result in pathological fracture (Fig. 8.21). In contrast a peripheral chondrosarcoma shows as a large mass growing outwards from the surface of the bone (Fig. 8.23). Both types characteristically show blotchy areas of calcification within the tumour mass. Magnetic resonance scanning is essential to define the soft tissue extension of the tumour (Figs 8.22 and 8.24).

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of bone

This rare highly malignant tumour includes many of the lesions once classified as fibrosarcoma, because their histology shows a predominance of fibroblast- type cells mixed with primitive histiocytes. It affects adults in the 20–60 age group, mainly occurring in the diaphysis of long bones, presenting with pain, swelling and sometimes pathological fracture.

Treatment is similar to osteosarcoma, requiring radical surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy.

Ewing’s1 tumour (endothelial sarcoma of bone)

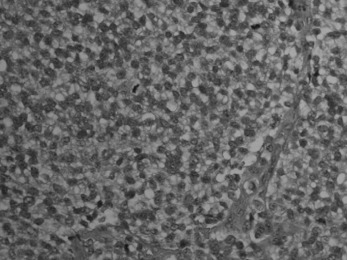

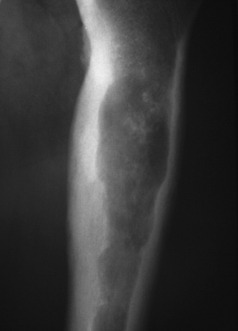

Pathology. The tumour is commonest in the shaft of the femur, tibia, or humerus. Unlike osteosarcoma, it arises in the diaphysis rather than the metaphysis of a bone. It probably develops from endothelial elements within the bone marrow, though the precise cell of origin is not known. The tumour tissue is soft and vascular. As it expands it gradually destroys the bone substance. There is a striking reaction beneath the periosteum, where abundant new bone is formed in successive layers (Fig. 8.13). Histologically the tumour consists of sheets of uniform small round cells (Fig. 8.26). The tumour metastasises early through the blood stream, especially to the lungs, and sometimes to other bones.

Clinical features. Children and adolescents in the 5–20 age group are the usual victims. Typically, there is local pain with rapidly increasing firm swelling over one of the long bones, usually near the middle of the shaft (in contrast to osteosarcoma which arises at the metaphysis). Local symptoms may be accompanied by fever, weight loss and general malaise. On examination the swelling is diffuse or fusiform, and of firm consistency. The overlying skin becomes stretched and warmer than normal due to the large size and vascularity of the tumour mass.

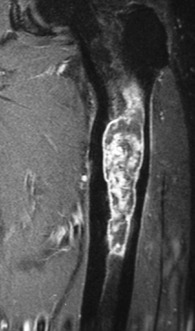

Imaging. Plain radiographs show destruction of bone substance with concentric layers of subperiosteal new bone (‘onion-peel’ appearance) (Fig. 8.27). MR scanning will reveal the extent of the large soft tissue mass of the tumour (Fig. 8.28). An isotope bone scan is also required in staging to detect any multifocal lesions. A radiograph or CT scan of the chest may show pulmonary metastases.

Fig. 8.28 (right) MR of the same patient as in Fig. 8.27. This shows there is extensive involvement of the tibial shaft, the cortex is breached and there is a large associated soft tissue mass.

Treatment. Chemotherapy differs from that used for osteosarcoma and a number of different drug combinations have been used and continue to evolve. A combination of vincristine, cyclophosphamide, dactinomycin, and doxorubicin is commonly recommended and is commenced as adjuvant therapy prior to any operative treatment. The tumour itself may be treated by radical operative excision with prosthetic replacement, or by amputation. Radiotherapy may be used as an alternative to operation, since the tumour is radiosensitive. Surgical excision with a special prosthesis adjustable for progressive limb growth is preferred for lower limb lesions, particularly in young children where leg length discrepancy and joint contractures may follow radiotherapy. Radiotherapy is usually reserved for upper limb tumours and for tumours at inaccessible sites such as the pelvis or spine.

Myeloma (myelomatosis; plasmacytoma)

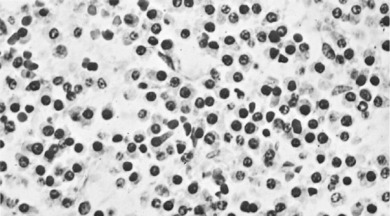

Pathology. It arises from the plasma cells of the bone marrow and is disseminated to many parts of the skeleton through the blood stream, so that by the time the patient seeks advice the tumour foci are usually multiple, affecting chiefly the bones that contain abundant red marrow. Less commonly the tumour may present as a solitary bone plasmacytoma (Fig. 8.29) with spread to other skeletal sites only after months or years. The lesions are mostly small and circumscribed (Figs 8.14 and 8.30) but occasionally large: the bone is simply replaced by tumour tissue and there is no reaction in the surrounding bone. Pathological fracture is common, especially in the spine (Fig. 8.30). Histologically the tumour consists ofa mass of small round cells of plasma-cell type: the cells may be somewhat larger than normal plasma cells, and less uniform (Fig. 8.31).

Imaging. Radiographs show multiple punched out lytic lesions, especially in bones containing red marrow, such as ribs, vertebral bodies, pelvic bones, skull, and proximal ends of femur and humerus (Fig. 8.30). Sometimes there is diffuse rarefaction of bone (Table 6.2, p. 77).

Investigations. There is microcytic anaemia. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is increased. Bence Jones protein is present in the urine in more than half the cases. Serum globulin is increased, often so much that the albumin–globulin ratio (normally 2:1) is reversed. Marrow biopsy usually shows a profusion of plasma cells which can be characterised by immunohistochemistry and cytogenetics to give more help in planning treatment and predicting prognosis.

Secondary (metastatic) tumours in bone

Pathology. The tumours that metastasise most readily to bone are carcinomas of the lung, breast, prostate, thyroid, and kidney (hypernephroma). Metastases occur most commonly in the parts of the skeleton that contain vascular marrow, especially the vertebral bodies, ribs, pelvis, and upper ends of the femur and humerus. The bone structure is simply destroyed and replaced by tumour tissue (Fig. 8.15). Pathological fracture is therefore very liable to occur.

Clinical features. Pain is the usual main symptom, but sometimes the disability is insignificant until a pathological fracture occurs. The spine is frequently involved, often with progressive neurological symptoms as well as local pain, from pressure on nerve roots or the spinal cord. In advanced widespread metastatic disease the patient may develop symptoms of hypercalcaemia,with nausea, vomiting, dehydration, and even coma. The primary tumour can usually be demonstrated.

Imaging. In plain radiographs the bone appears to have been eaten away so that there is a clear circumscribed area of lysis, without any reaction in the surrounding bone (Fig. 8.32). Exceptionally, new bone is laid down within the metastasis, causing marked sclerosis – the exact opposite to the usual osteolytic lesion. This type is almost confined to secondary deposits from prostatic carcinoma. In cases of diffuse infiltration there may be widespread osteoporosis (Table 6.2, p. 77). A radiograph or CT scan of the chest should always be obtained because of the possibility that metastases may be present in the lungs.

Technetium isotope scanning is the best technique for detecting occult metastatic deposits in the skeleton, as areas of increased uptake (Fig. 2.14B). These may be apparent long before the lesions are visible in plain radiographs, making it a very sensitive screening method. Magnetic resonance imaging is an even more sensitive method of screening, particularly for the detection of spinal metastases.

Treatment. Radiotherapy is a valuable palliative treatment, particularly in more localised disease. Chemotherapy is sometimes appropriate (see p. 117). Radio-active iodine is valuable for metastases from carcinoma of the thyroid. Hormone analogue therapy may be appropriate for metastases from the breast or prostate, and in selected cases adrenalectomy and hypophysectomy have proved worthwhile in slowing the progress of the disease when other measures have failed. In the presence of life-threatening hypercalcaemia, treatment by bisphosphonates is valuable in that it inhibits further bone resorption and may also relieve bone pain. Local splintage may be required, but metallic internal fixation, or even custom prosthetic replacement of bone, is used increasingly for the treatment of impending or pathological fracture of the long bones as a means of maintaining independent function. Strong analgesics and sedatives may be required and a multi-disciplinary team is essential for the overall management of severe intractable pain.

Bone changes in leukaemia and lymphoma

This is a convenient place to note that changes may occur in the skeleton in leukaemia and in Hodgkin’s disease or related lymphomas. In leukaemia the changes are due to infiltration of bone by proliferating white cells, and they are seen most commonly in subacute lymphatic leukaemia in children. Characteristically there are zones of rarefaction with delicate subperiosteal new bone formation in the metaphysial regions of the femur or humerus, or in the spine or pelvis. Leukaemia is also an occasional cause of diffuse widespread rarefaction of the skeleton (Table 6.2, p. 77).

TUMOUR-LIKE LESIONS OF BONE

SIMPLE BONE CYST (Solitary bone cyst; unicameral bone cyst)

Imaging. Plain radiographs show a circumscribed area of lucency with only a thin surrounding zone of sclerosis (Fig. 8.33A). The cyst may appear faintlyloculated and the overlying cortex may be thinned, or if fractured, a cortical fragment may drop into the cyst (‘fallen fragment’).

Treatment. Small uncomplicated cysts do not require treatment, since they tend to heal after skeletal maturity (Fig. 8.33B), but they should be kept under periodic observation. A large cyst may be curetted and packed with bone chips, but percutaneous aspiration and injection of corticosteroid solution or autogenous bone marrow into the cyst have now replaced operative treatment as the principal method of management. If fracture occurs each case must be treated on its merits: most heal with conservative treatment, but if internal fixation is required it should be combined with bone grafting.

ANEURYSMAL BONE CYST

Aneurysmal bone cysts also occur in children or young adults, usually before epiphyseal closure, but they are distinct from the simple bone cysts described above. Their origin is unknown: the term ‘aneurysmal’ signifies no more than a seeming ‘blown-out’ distension of one surface of the bone. There is no relationship to arterial aneurysm. The cyst may bulge into the soft tissues, contained only by periosteum and a thin shell of newly formed cortex. The lining consists of connective tissue with numerous vascular spaces and some giant cells; the cyst contains fluid blood.

Imaging. Plain radiographs show the cyst to be situated eccentrically in the bone; it presents a characteristic ‘blown-out’ appearance, as already mentioned (Fig. 8.34). These features distinguish it from the ordinary simple bone cyst, which is placed more centrally in the shaft and expands the bone uniformly without periosteal reaction. CT or MRI scanning may provide additional information on the extent of cortical destruction and may also demonstrate the multiple fluid levels that are typical of aneurysmal bone cysts.

LOCALISED FIBROUS DYSPLASIA OF BONE (Monostotic fibrous dysplasia)

In this condition a solitary area of bone is partly replaced by fibrous tissue, in which scanty bone trabeculae may persist. The cause is unknown, as also is its relationship to polyostotic fibrous dysplasia (p. 68). It is not related to the fibroblastic changes seen in association with the ‘brown cysts’ of hyperparathyroidism (p. 73).

Pathology. One of the limb bones is usually the site affected, commonly the central fibrous lesion expands the medullary cavity at the expense of the bone, which is weakened and may fracture.

Imaging. Plain radiographs show a zone of lucency within the bone, often with a homogeneous ‘ground-glass’ appearance and a thick sclerotic rim (Fig. 8.35). In larger lesions softening of the bone and repeated microfractures may result in progressive deformity, such as the ‘shepherd’s crook’ of the proximal femur.

OTHER LOCAL AFFECTIONS OF BONE

There is a miscellaneous group of solitary lesions of bone that do not fall into the category of infection or tumour. The most important members of the group are osteochondritis juvenilis and localised fibrous dysplasia of bone.

OSTEOCHONDRITIS JUVENILIS (Osteochondrosis)

The term osteochondritis juvenilis, or simply osteochondritis, is used to describe certain obscure affections of developing bony nuclei in children and adolescents. The term has also been used, wrongly, for some other affections of epiphyses or apophyses that are more likely traumatic in origin. Typically, a bony centre affected by osteochondritis becomes temporarily softened, and while in the softened state it is liable to deformation by pressure. The disease runs a course of variable length (often about 3 years), but eventually spontaneous rehardening occurs. The precise cause of the disease is unknown, but it is widely believed that temporary interruption of the blood supply to the affected epiphysis is the predominant factor. It should be noted that osteochondritis juvenilis is entirely distinct from osteochondritis dissecans (p. 153).

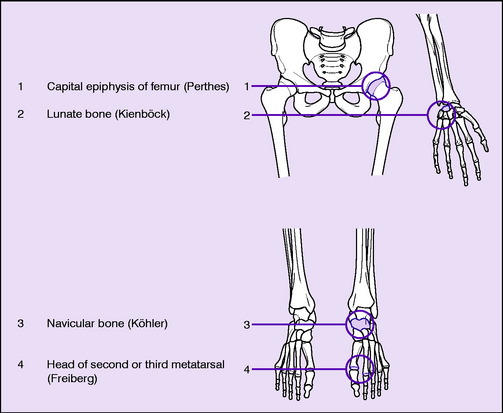

Sites. Osteochondritis juvenilis is recognised at the following sites (Table 8.2), though the pathology may not be identical at each site:

Table 8.2 Common sites of osteochondritis or related changes.

|

A similar radiographic change in the central epiphysis of a vertebral body (Calvé’s disease, p. 235) is now generally ascribed to eosinophilic granuloma rather than to osteochondritis. And the affection of the ‘ring’ epiphyses of the vertebral bodies in the thoracic region of the spine known as Scheuermann’s disease or adolescent kyphosis (p. 232), again formerly thought to be an example of osteochondritis, is also now believed to be of different pathology. In brief, only the sites shown in Table 8.2 are now regarded as those where true osteochondritis commonly occurs.

Radiological appearances that bear some resemblance to the changes of osteochondritis are also seen in cases of pain at the apophysis of the tibial tubercle (Osgood–Schlatter’s disease, p. 415) and at the apophysis of the calcaneus (Sever’s disease, p. 448). These conditions were formerly thought to be examples of osteochondritis, but it is now recognised that they are traumatic in origin. There is simply a chronic strain of the apophysis from the pull of the tendon that is inserted into it. This type of lesion is now usually termed apophysitis.

Pathology. In a typical example of osteochondritis the histological and radiological evidence suggests that the affected bony centre undergoes partial necrosis, possibly from interference with its blood supply. The necrotic bone is invaded by granulation tissue, broken up, and eventually removed by osteoclasts. Duringthis stage of fragmentation the centre is liable to deformation if subjected to pressure (Fig. 8.37). The dead tissue is gradually replaced by new living bone trabeculae and eventually the bone texture is restored to normal; but if deformation has been allowed to take place there is permanent alteration of shape.

Further details of these disorders will be found in the chapters dealing with individual regions.