12 Body Peeling

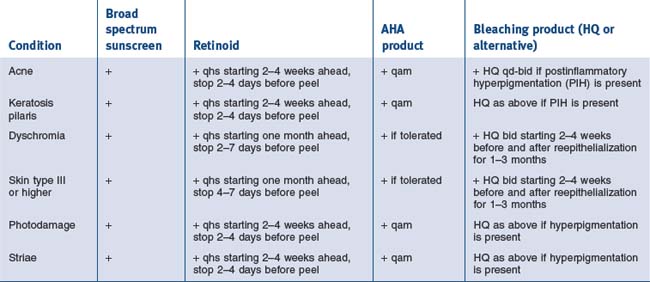

When discussing the approach to chemical peeling off the face, adjectives such as conservative and gradual should come to mind. Common indications are much the same as their facial counterparts and can be grouped into those that would be best treated with superficial peels and those that would benefit from medium-depth peels (see Table 12.1).

Table 12.1 Indications for superficial and medium-depth peels

| Superficial peels | Medium-depth peels |

|---|---|

The Procedures on Location

• Chest and neck

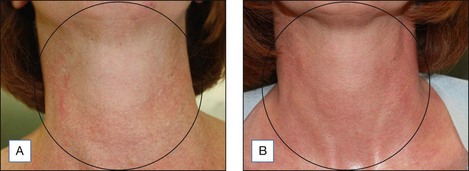

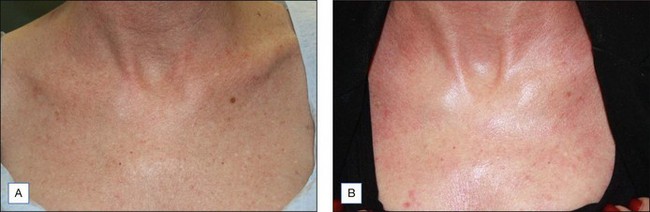

At this point, 25% TCA is applied. The resulting stinging sensation is brief (a few minutes) and patients can be consoled with the fact that cool compresses will soon be applied once the appropriate level of frosting appears. The TCA solution is typically applied using large, smooth cotton applicators so as not to introduce additional friction to the process which would unintentionally create a deeper peel. To promote patient comfort further the application is done in an expedited fashion. Frosting on nonfacial areas is usually slower, so it is important not to over treat a given areas because the frost has not uniformly appeared. At the maximum, a level 2 frost (even white enamel with erythematous background) should be the goal for medium-depth peels off the face while areas such as the neck should undergo less intense frosting. The major determinants for the degree of TCA penetration or frost are as follows: extent of degreasing, the amount of peeling agent and concentration used, type of applicator chosen, the duration of contact with skin, the degree of rubbing/pressure of application, sebaceous nature of the skin being treated and the number of coats applied. Figure 12.1 shows improvement of neck photodamage following Jessner’s/25% TCA peel.

• Striae

Priming of the skin as listed in Table 12.1 is encouraged. The skin is prepared by degreasing it with alcohol and acetone on a gauze pad. Proximal and distal limits of the striae are then marked. Local infiltration is with 2% lidocaine with epinephrine. After anesthesia is achieved, an 18G Nokor BD needle is inserted first at a 45° angle. Once the deep dermal plane is entered, the needle is adjusted to a more shallow angle. Back and forth movements along the length of striae are performed until no resistance is met and dissection of this plane is accomplished. A blush of purple ecchymosis is expected toward the end of the procedure and may be present for 2–5 days. Following subcision, the area is re-swabbed with alcohol and 3–4 coats of 20% TCA (using a cotton tipped applicator) is applied directly to the striae (Figure 12.2). A faint frost will be appreciated.

Alam M, Omura N, Kaminer MS. Subcision for acne scarring: technique and outcomes in 40 patients. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31:310-317.

Baumann L. Depigmenting agents. In: Day DJ, editor. Understanding hyperpigmentation. What you need to know. Aurora, California: Intellyst medical communications, 2004.

Brody HJ. Chemical peeling and resurfacing, 2nd ed. Atlanta: Emory University Digital Library Publications; 2008.

Coleman WP, Futrell JM. The Glycolic acid trichloroacetic acid peel. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1994;20:76-80.

Cook KK, Cook WR. Chemical peel of nonfacial skin using glycolic acid gel augmented with TCA and neutralized based on visual staging. Dermatologic Surgery. 2000;26:994-999.

Grimes PE. Glycolic acid peels in blacks. In: Moy R, Luffman D, Kakita L, editors. Glycolic acid peels. Marcel Dekker, Inc; 2002:179-186.

Hevia O, Nemeth AJ, Taylor JR. Tretinoin accelerates healing after trichloroacetic acid chemical peel. Archives of Dermatology. 1991;127:678-682.

Hexsel DM, Mazzucco R. Subcision a treatment for cellulite. International Journal of Dermatology. 2000;39:539-544.

Kang WH, et al. Atrophic acne scar treatment using triple combination therapy: dot peeling, subcision and fractional laser. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2009;11:212-215.

Luis-Montoya P, et al. Evaluation of subcision as a treatment for cutaneous striae. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2005;4:346-350.

Maibach HF, Rovee DT. Epidermal Wounds Healing. St Louis: Mosby; 1972.

Monheit GD. The Jessner’s and TCA peel: A medium depth chemical peel. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1989;15:945-950.

Rendon MI, Gaviria JI. Review of skin-lightening agents. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31:886-889.

Rubin M. Manual of chemical peels. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1995. pp. 120–121

Sato MS, et al. Clinical evaluation of the efficacy of trichloroacetic acid and subcision, combined or isolated, for abdominal striae. Sociedad Brasileira de Dermatologia-Surgical and Cosmetic Dermatology. Online access for English translation at. www.surgicalcosmetic.org.br, 2009. 1(4)