79 Blunt Abdominal Trauma

• Intraperitoneal bleeding is an immediately life-threatening injury after blunt trauma.

• Management of intraperitoneal bleeding takes priority over injuries to many other systems (Box 79.1).

• Physical examination is unreliable for predicting the presence or absence of injury except for certain high-risk findings such as the seat belt and Kehr signs.

• Bedside ultrasonography is an excellent initial screening tool that facilitates early triage of patients for either laparotomy or transfer to the radiology suite for computed tomography (CT).

• Helical CT provides excellent, accurate detail of intraperitoneal injuries. CT is highly sensitive for solid organ injuries but has lower sensitivity for detecting pancreatic, small bowel, and diaphragmatic injuries.

• Detailed CT images allow grading of organ injuries and nonoperative management of solid organ trauma in stable patients and the use of angiographic embolization in patients with liver, spleen, and renal injuries.

• Early detection of intraperitoneal injuries after blunt trauma and a team approach to management of these injuries significantly improve mortality rates.

Box 79.1 Management of Intraperitoneal Injuries

Intraperitoneal bleeding is an immediately life-threatening injury after blunt trauma, and management of intraperitoneal bleeding takes priority over injuries to other systems.

Physical examination is unreliable in predicting the presence or absence of injury except for certain high-risk findings such as the seat belt and Kehr signs.

Bedside ultrasonography is an excellent initial screening tool that facilitates early triage of patients to either laparotomy or the radiology suite for computed tomography (CT).

CT is highly sensitive for detecting solid organ injuries but has lower sensitivity for detecting pancreatic, small bowel, and diaphragmatic injuries.

Detailed CT allows grading of organ injuries and nonoperative management of solid organ trauma in stable patients and the use of angiographic embolization in patients with liver, spleen, and renal injuries.

Epidemiology

In the United States, trauma is a serious health problem, both as a cause of mortality and as a significant financial burden.1 In recent years, management of blunt abdominal trauma has started to change because of the high success rates of more conservative, nonoperative treatment. Such management is a safer, successful, and more cost-effective way to care for these patients and consequently has led to an increasingly selective approach to performing explorative laparotomy.

Abdominal injuries occur in approximately 1% of all trauma patients.2 Blunt trauma is far more common than penetrating trauma in the United States and is associated with greater mortality because of multiple related injuries and greater diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. The mechanism of blunt trauma may range from high-speed injuries to minor falls or direct blows to the abdomen. Motor vehicle collisions are responsible for approximately 75%, blows to the abdomen for approximately 15%, and falls for approximately 9% of injuries.3 Evaluation is further complicated by extraabdominal injuries, as well as by altered mental status from head trauma, alcohol intoxication, or recreational drugs.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Patients in shock usually demonstrate tachycardia. However, up to 44% of trauma patients in shock may have relative bradycardia, defined as a heart rate of less than 90 beats per minute and a systolic blood pressure lower than 90 mm Hg. Relative bradycardia has been identified as an independent risk factor for mortality.4

Abdominal tenderness is often absent in patients with intraperitoneal injury. Drugs, alcohol, hypotension, and the presence of head injury reduce the patient’s ability to sense pain or tenderness. Additionally, other significant injuries such as fractures or large lacerations may distract the patient from feeling the pain associated with abdominal injury. In a large prospective study, 19% of patients with positive findings on CT for intraabdominal injury did not have abdominal tenderness.3 Other studies have reported abdominal tenderness in only 42% to 75% of patients with small bowel or mesenteric injury.5,6 The sensitivity, specificity, and negative and positive predictive values of abdominal pain or tenderness in predicting intraabdominal injury are reported to be 82%, 45%, 93%, and 21%, respectively.7 Furthermore, patients with chest wall injuries and pneumothorax are at risk for injury and may not exhibit abdominal pain or tenderness. Thus, it is important to avoid relying solely on the physical examination, especially in a multitrauma patient or one with altered mental status, when deciding whether to perform diagnostic testing on a patient after blunt abdominal trauma.

Evaluation

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Prehospital hypotension indicates the need for diagnostic imaging of the abdomen.

Abdominal ecchymosis is predictive of intraperitoneal injury.

The presence of a Chance fracture is predictive of intraperitoneal injury.

Left shoulder pain suggests splenic injury.

Low rib fractures are associated with liver and spleen injuries.

Differential Diagnosis

Chance Fractures

A single lap belt restraint can result in Chance fractures of the lumbar spine. In a recent report, 33% of patients with Chance fractures had associated intraabdominal injury, and of these patients, 22% had hollow viscus injuries.8 In other studies, up to 89% of patients with Chance fractures had small bowel injuries.5,9 Some centers consider the presence of Chance fractures and the seat belt sign to be an indication for exploratory laparotomy.

Upper Abdominal Injuries

Low rib injuries may be associated with spleen or liver trauma, as well as kidney injuries. The incidence of splenic injury in patients with “isolated” low rib pain or tenderness (no abdominal tenderness) was 3% in a recent report. Although the only prospective study on the subject is not definitive, it suggests that patients with pleuritic pain and isolated low left rib pain or tenderness, regardless of whether abdominal tenderness is present, should undergo imaging.10 In addition, patients with abdominal tenderness following low chest trauma should undergo diagnostic imaging (e.g., CT).

Lower Abdominal Injuries

Blunt abdominal trauma may result in retroperitoneal injury to the kidneys or ureters. Intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal bladder rupture may also occur. Major pelvic fractures are associated with abdominal injuries in 30% of patients.11 Injury to the abdominal aorta is rare after blunt abdominal trauma. Other less serious injuries are abdominal wall hematomas, which do not usually require operative intervention but can result in significant blood loss.

Injuries with Delayed Presentation

Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia can also occur in delayed fashion. These injuries are frequently missed because the sensitivity of CT for diaphragmatic injuries is low and the majority of patients have associated injuries.12 Most of these injuries result from a vehicular collision. Because the right hemidiaphragm is protected by the liver, the left hemidiaphragm is more commonly involved.

Solid Organ Injuries

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

1. Follow the advanced trauma life support protocols for initial resuscitation.

2. Determine the stability of the patient.

3. Perform chest and pelvic radiography on all unstable trauma patients.

4. Perform ultrasound examination on all major trauma patients.

5. Arrange transfer immediately for all patients with multisystem trauma or with the potential for intraperitoneal injury if a trauma surgeon is not available.

6. Triage the patient to either computed tomography scanning, laparotomy, the angiography suite (pelvic fractures or for embolization of abdominal injuries), intensive care unit, admission for observation, or discharge.

The Unstable Patient

Immediate Operative Intervention

Focused Abdominal Sonography for Trauma

Bedside ultrasonography has many advantages as an initial triage tool in an unstable trauma patient. It is readily accessible at most level I trauma centers and, in the hands of trained EPs, is accurate in detecting hemoperitoneum.13 Focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) can be performed in less than 2 minutes and can triage patients to the operating room or further diagnostic testing, depending on the patient’s stability. In trauma patients, the incidence of an indeterminate sonographic result is low (less than 7%),14 and the reported sensitivity and negative predictive value in unstable patients approach 100%.15,16 The presence of hemoperitoneum in an unstable patient is an indication for operative intervention. The only caveat is that in patients with major pelvic trauma who may have bladder rupture with uroperitoneum, diagnostic peritoneal aspiration may be indicated to distinguish blood from urine. If the sonographic findings are negative, other sources of bleeding should be addressed, such as pelvic fractures and retroperitoneal bleeding.

The Stable Patient

Laboratory Testing

Laboratory tests are rarely helpful in the initial resuscitation of patients after blunt abdominal trauma. The utility of ordering individual laboratory tests when a specific clinical need is present versus routinely ordering a standard “trauma panel” has been studied. A significant cost savings, without adverse events, occurs if this practice is followed.17,18

All women of childbearing age should undergo a pregnancy test and be questioned about whether they are pregnant. Serial ultrasonography can be used as the initial and often definitive modality, and CT should be used sparingly in the first 20 weeks of gestation to avoid unnecessary exposure to radiation.19

Lactate levels and base excess are two laboratory tests that have been shown to predict bleeding.20 In one recent study of stable trauma patients, an increased lactate level (>2.5 mmol/L in ethanol-negative patients and >3 mmol/L in ethanol-positive patients) and an increased base deficit (>0.0 in ethanol-negative patients and >3.0 in ethanol-positive patients) were associated with a significant risk for torso injury, whereas patients with a normal base deficit were unlikely to have injury.21 Other authors consider a base deficit cutoff value of 6 or less to be predictive of intraabdominal injury and an indication for diagnostic imaging or DPL.22

Urinalysis should be performed in all blunt trauma patients with a significant mechanism of injury. The presence of gross hematuria is an indication for evaluation of the genitourinary tract. Microscopic hematuria is a sign of mild renal injury that does not require treatment; its presence in a stable patient without a significant deceleration injury (associated with renal pedicle injury) is not an indication for additional diagnostic imaging. Some evidence also suggests that microscopic hematuria consisting of 25 or more red blood cells per high-power field may be one of the predictors of intraperitoneal injury.23

Plain Radiographs

Plain radiographs cannot rule out intraperitoneal injury after blunt trauma. Chest radiography may be used to diagnose a diaphragmatic rupture (Fig. 79.1). However, plain radiographs of the chest are diagnostic of diaphragmatic rupture in only 50% of patients with left-sided rupture and in only 17% of those with right-sided rupture.24,25 Free air is a rare finding on an upright chest radiograph that indicates hollow viscus rupture (stomach or colon), but upright chest radiography is not usually feasible after blunt trauma. Thus, plain radiographs should not be used to rule out intraperitoneal injury.

Ultrasonography

FAST is recommended for all blunt trauma patients with any significant mechanism of injury as an initial screening test regardless of patient stability. Ultrasonography is now listed in the advanced trauma life support algorithm for abdominal trauma and is used in the majority of level I trauma centers.26 In the blunt trauma setting, ultrasonography has become part of the secondary survey to detect hemoperitoneum as an indicator of intraperitoneal injury.

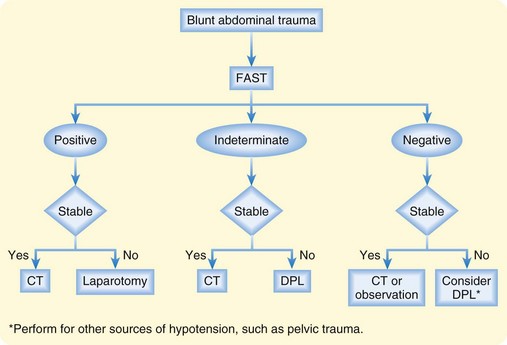

If the sonogram shows free fluid and the patient is hemodynamically unstable, exploratory laparotomy is indicated. A stable patient with free fluid should undergo CT immediately to identify the type of injury and determine the need for laparotomy. A clinical algorithm that incorporates FAST is presented in Figure 79.2.

Fig. 79.2 Algorithm for the management of blunt abdominal trauma.

(From Rosen CL, Promes SB. Use of ultrasound in emergency medicine. Clinical bulletin: State of the Art Emergency Medicine 2003;7[2]:1. Reprinted with permission from Sterling Healthcare. All rights reserved.)

The major limitation of ultrasonography is its inability to identify or grade solid organ injury. Its sensitivity for detecting hemoperitoneum as an indicator of intraperitoneal injury ranges from 76% to 90%, and its specificity ranges from 95% to 100%.13 However, its sensitivity is as low as 33% with splenic injuries and 12% with hepatic injuries for identifying encapsulated solid organ bleeding.13,27 Ultrasonography is also limited in assessing injuries that are not associated with a large amount of hemoperitoneum, such as retroperitoneal bleeding and injuries to the small bowel or diaphragm. Up to one third of patients with intraperitoneal injury will have negative findings on FAST, including as many as 10% of patients who require surgery.28 Thus, FAST does not replace more definitive tests such as CT, but it can be a triage tool to expedite the evaluation and management of patients with blunt abdominal trauma. The amount of intraperitoneal fluid that must be present to have abnormal FAST findings is at least 150 mL and may be as much as 1 L.29,30

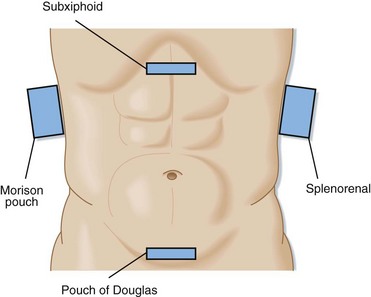

The technique of bedside ultrasonography in trauma patients consists of four standard views (Fig. 79.3): right upper quadrant (Morison pouch), subxiphoid, left upper quadrant, and suprapubic (pouch of Douglas). Although this examination has no standard sequence, the suprapubic view takes advantage of the full bladder as a sonographic window and should therefore be obtained before placement of a Foley catheter. Most operators start with the Morison pouch view because it is technically the easiest.

Obtaining all the views rather than one single view increases the sensitivity of the test.31 Performing serial examinations every 30 minutes into the resuscitation—or if a change in clinical status occurs—increases the sensitivity further. Trendelenburg positioning may improve the sensitivity by causing the hemoperitoneum to pool in dependent spaces. The differential diagnosis for fluid seen on ultrasonography includes ascites, as well as urine from intraperitoneal bladder rupture. All fluid will result in the same black stripe seen on the sonogram.

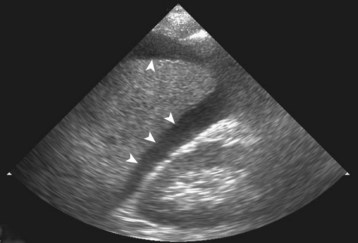

The finding suggestive of injury is hemoperitoneum, which appears as a black (anechoic) stripe between the kidney and the liver (Fig. 79.4), between the kidney and the spleen, or posterior to the bladder. Because ultrasonography is insensitive in detecting actual parenchymal injury, the operator should not waste time evaluating the spleen and liver for evidence of injury.

Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage

DPL was formerly the primary method for evaluating unstable patients after blunt abdominal trauma, but its use has markedly decreased with the widespread application of bedside ultrasonography. Currently, DPL is indicated when ultrasonography is unavailable or if the results are indeterminate in an unstable patient. Some authors recommend DPL to confirm the absence of hemoperitoneum in unstable patients with negative results on ultrasonography.32

DPL is very sensitive in detecting intraperitoneal bleeding, can be performed rapidly, and is inexpensive. It can detect small amounts of intraperitoneal blood (as little as 20 mL).33 The accuracy of DPL for predicting or ruling out intraperitoneal bleeding is close to 98%.34,35 DPL has, however, been shown to be less accurate in patients with major pelvic fractures. The false-positive rate may be higher in this group of patients because of the presence of uroperitoneum as a result of bladder injury. Consequently, in the presence of a pelvic fracture, diagnostic peritoneal aspiration may be indicated to determine whether a positive FAST result is due to blood or urine.36

The disadvantages of DPL are that it is invasive, does not identify the specific organ that is injured, and does not sample the retroperitoneal space. It will also detect small amounts of bleeding associated with injuries that do not require operative intervention. The nontherapeutic laparotomy rate for patients with a positive DPL finding is reported to be as high as 35%.37 Thus, in stable patients, a positive DPL result is not an indication for laparotomy.

Computed Tomography

CT is indicated in stable patients when intraabdominal injury is clinically of concern because of abdominal wall findings, traumatic distracting injuries, and a significant mechanism of injury. The presence of distracting injury and the need for operative intervention for other injuries (e.g., orthopedic injuries) are also indications for performing CT. In awake patients who have a reliable abdominal examination and no abdominal tenderness, the yield of performing abdominal CT scanning because they are undergoing extraabdominal surgery is very low. Less than 2% of patients undergoing abdominal CT scanning only because of the need for general anesthesia for urgent extraabdominal surgery actually had an abdominal injury, and less than 0.5% required laparotomy.38,39

Recent studies have looked at determining clinical predictors for identifying patients at low risk for intraperitoneal injury after blunt trauma who may not need CT. One such clinical prediction rule consists of a Glasgow Coma Scale score of less than 14, costal margin tenderness, abdominal tenderness, femoral fracture, hematuria consisting of greater than 25 red blood cells per high-power field, hematocrit of less than 30%, and abnormal chest radiograph findings (pneumothorax or rib fracture). In the absence of any of these clinical variables, patients are at very low risk of having intraperitoneal injury (96% sensitivity and 99% negative predictive value).23

Many trauma centers in the United States and Europe are using a newer technique, the “pan scan,” for obtaining a rapid CT scan of the head, neck, and torso in patients with a high mechanism of trauma who are at higher risk for traumatic injuries. The advantage of this technique is that it is faster than performing segmental, sequential CT scans and may detect injuries that would otherwise be missed or diagnosed in delayed fashion, such as spine and chest injuries. The biggest risk, however, is that this technique will be overused and expose patients to unnecessary radiation and cancer risk. The exact indications for performing a pan scan are controversial. However, a conservative approach would be to obtain a pan scan in patients with a major traumatic mechanism who are also not evaluable because of head injury, intubation, or depressed mental status from alcohol. A pan scan is also recommended for elderly trauma patients who may sustain significant injuries with lesser mechanisms and for patients with prehospital hypotension who are stable in the emergency department because they are also at risk for torso trauma.40,41

CT is very accurate in diagnosing intraperitoneal injury, especially for detecting solid organ injury, as stated previously. Another advantage of CT is its higher accuracy and sensitivity than plain radiographs for detecting fractures of the thoracolumbar spine (TLS). In one prospective study, the accuracy of CT of the torso for detecting TLS fractures was 99% versus 87% for plain radiographs, with the “gold standard” for fracture being the discharge diagnosis of acute fractures confirmed by thin-cut CT or clinical examination of the patient when alert (or both). It is also much faster to obtain a torso CT scan than it is to obtain multiple plain radiographic spine images.42

The limitations of CT lie in its low sensitivity for diaphragm, mesenteric, hollow viscus, and pancreatic injuries. Although the newer-generation multidetector CT scanners appear to have better resolution and sensitivity for these rare injuries, they are still not highly accurate. The sensitivity for diaphragmatic injury is between 67% and 84%, with specificities reported to be between 77% and 100%.12,43–46

The sensitivity of CT for detecting hollow viscus injury is reported to range from 83% to 94%.10,12,46–50 Multidetector CT without oral contrast enhancement was 82% sensitive and 99% specific for detecting bowel and mesenteric injuries.51 The reported sensitivity of CT for detecting pancreatic injuries after blunt trauma ranges from 50% to 68%, even with spiral CT technology.52,53 The use of oral contrast is not associated with an increase in sensitivity for detecting pancreatic injury.53 In a recent multicenter study, the sensitivity of CT was 76% for pancreatic injuries and 70% for duodenal injuries.54

Oral Contrast or No Oral Contrast?

An ongoing controversy on the use of CT scanning for blunt abdominal trauma is the utility of oral contrast versus intravenous contrast alone. Oral contrast is associated with increased time and the potential for vomiting, aspiration, and other complications, as well as discomfort if a nasogastric tube is placed. Several studies have documented that oral contrast enhancement is not essential for identifying solid organ, mesenteric, or bowel injuries.55–58 Because use remains controversial and local customs often prevail, oral contrast agents are still commonly used in many trauma centers.

Findings in Patients with Blunt Abdominal Trauma

Isolated intraperitoneal fluid in patients without solid organ injury is associated with a high incidence of bowel or mesenteric injury. In patients without solid organ injury and with more than trace amounts of free fluid, the therapeutic laparotomy rate is 54% to 94%.59 At surgery, small bowel, mesenteric, and diaphragm injuries are usually found.

Treatment

Intravenous fluid resuscitation with normal saline or lactated Ringer solution is indicated for patients who are hemodynamically unstable (tachycardia or hypotension). The optimal amount and goal of resuscitation are controversial. Although the standard has been to immediately infuse 2 L of crystalloid followed by blood transfusion in patients with continued instability, many institutions move rapidly to blood transfusion and limit resuscitation so that patients are kept “underresuscitated” with a systolic blood pressure of approximately 90 mm Hg.32,60 This can usually be accomplished with type O-negative blood in women of childbearing age and type O-positive in all others. Once the bleeding lesion is identified and definitively controlled, full resuscitation is instituted. However, this practice is not typically recommended for patients with possible traumatic brain injury.

For patients requiring large amounts of blood products, new evidence suggests that early administration of plasma and a higher ratio of plasma to packed red blood cells (PRBCs) transfused will result in lower mortality rates. In patients who require massive transfusion (defined as 10 or more units of PRBCs in 24 hours), it is recommended that they receive plasma, platelets, and PRBCs in a ratio close to 1:1:1.61,62

Nonoperative Treatment

Many reports in the surgical literature document success with nonoperative management of patients with spleen and liver lacerations.63 Most centers, however, consider the presence of hemodynamic instability or transfusion requirements as indications to operate on patients with solid organ injuries. Age may also be used as an indicator for surgery; children do well with nonoperative management, whereas elderly patients may have lower success rates with nonoperative care. Nonoperative salvage rates in patients with lacerations of the spleen are 94%, and up to 80% of grade 4 and 5 splenic injuries can be managed successfully without operative intervention.64

In one prospective study, the failure rate of nonoperative treatment of kidney, liver, and splenic lacerations was 22%; the failure rate was higher for splenic injury than for liver or kidney injuries.65 Independent predictors of failure of nonoperative management were fluid identified on screening ultrasonography, significant blood on CT (>300 mL), and the need for blood transfusion.65

Interventional Radiology

In major trauma centers, interventional radiologists in conjunction with trauma surgeons are performing angiography with embolization instead of operative management. The nonoperative salvage rate in patients with splenic lacerations who undergo embolization is 90%.64 Angiography with embolization may be performed in patients who are hemodynamically stable and do not have associated hollow viscus or other injuries requiring operative intervention.66,67

For splenic injuries, arterial embolization may be indicated for patients with active extravasation of contrast material, pseudoaneurysm or arteriovenous fistula, large hemoperitoneum, and a higher grade of injury (III to V), assuming that no indications for operative intervention are present. The combination of contrast blush and significant hemoperitoneum may also predict a high failure rate for nonoperative management and may be an indication for arterial embolization or laparotomy with splenectomy.68

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education (Admission and Discharge)

Tips and Tricks

Do not underestimate the mechanism of injury. A significant mechanism of injury requires evaluation for intraperitoneal injury even if the patient is stable and the findings on physical examination are normal.

The presence or absence of abdominal tenderness does not predict intraperitoneal injury.

Alcohol and distracting injuries can make the findings on physical examination unreliable.

All blunt abdominal trauma patients should undergo FAST.

Before performing DPL, place a nasogastric tube and Foley catheter and obtain a pelvic radiograph.

Positive FAST findings or DPL aspirate in an unstable patient is an indication for laparotomy.

Unstable patients should not be transferred to the radiology suite for CT.

Significant intraperitoneal fluid without solid organ injury on a CT scan suggests the presence of small bowel injury.

CT can fail to identify injuries of the pancreas, diaphragm, small bowel, and mesenterium.

ACEP Clinical Policies Committee. Clinical Policies Subcommittee on Acute Blunt Abdominal Trauma: clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with acute blunt abdominal trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:278–290.

Borgman MA, Spinella PC, Perkins JG, et al. The ratio of blood products transfused affects mortality in patients receiving massive transfusion at a combat support hospital. J Trauma. 2007;63:805–813.

Farahmand N, Sirlin CB, Brown MA. Hypotensive patients with blunt abdominal trauma: performance of screening US. Emerg Radiol. 2005;235:436–443.

Haan JM, Bochicchio GV, Kramer N, et al. Non-operative management of blunt splenic injury: a 5-year experience. J Trauma. 2005;58:492–498.

Hauser CJ, Visvikis G, Hinrichs C, et al. Prospective validation of computed tomographic screening of the thoracolumbar spine in trauma. J Trauma. 2003;55:228–235.

Holmes JF, Schauer BA, Nguyen H, et al. Is definitive abdominal evaluation required in blunt trauma victims undergoing urgent extra-abdominal surgery? Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:707–711.

Holmes JF, Wisner DH, McGahan JP, et al. Clinical prediction rules for identifying adults at very low risk for intra-abdominal injuries after blunt trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:575–584.

Tayal V, Neilsen A, Jones A, et al. Accuracy of trauma ultrasound in major pelvic injury. J Trauma. 2006;61:1453–1457.

Velmahos GC, Toutouzas KG, Radin R, et al. Non-operative treatment of blunt injury to solid abdominal organs: a prospective study. Arch Surg. 2003;138:844–851.

Zink KA, Sambasivan CN, Holcomb JB, et al. A high ratio of plasma and platelets to packed red blood cells in the first 6 hours of massive transfusion improves outcomes in a large multicenter study. Am J Surg. 2009;197:565–570.

1 Hoyt DB, Coimbra R, Potenza B. Management of acute trauma. In: Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, et al. Sabiston textbook of surgery. 17th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:483–529.

2 Rutledge R, Hunt JP, Lentz CW, et al. A statewide, population-based time-series analysis of the increasing frequency of non-operative management of abdominal solid organ injury. Ann Surg. 1995;222:311–322.

3 Livingston DH, Lavery RF, Passannante MR, et al. Admission for observation is not necessary after a negative abdominal computed tomographic scan in patients with suspected blunt abdominal trauma: results of a prospective, multi-institutional trial. J Trauma. 1998;44:273–280.

4 Ley EJ, Salim A, Kohanzadeh S, et al. Relative bradycardia in hypotensive trauma patients: a reappraisal. J Trauma. 2009;67:1051–1054.

5 Fakhry SM, Watts DD, Luchette FA. Current diagnostic approaches lack sensitivity in the diagnosis of perforated blunt small bowel injury: analysis of 275,557 trauma admissions from the EAST multi-institutional HVI trial. J Trauma. 2003;54:295–306.

6 Pikoulis E, Delis S, Psalidas N, et al. Presentation of blunt small intestinal and mesenteric injuries. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2000;82:103–106.

7 Ferrera PC, Verdile VP, Bartfield JM, et al. Injuries distracting from intraabdominal injuries after blunt trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 1998;16:145–149.

8 Tyroch AH, McGuire EL, McLean SF, et al. The association between Chance fractures and intra-abdominal injuries revisited: a multicenter review. Am Surg. 2005;71:434–438.

9 Anderson PA, Rivara FP, Maier RV, et al. The epidemiology of seatbelt-associated injuries. J Trauma. 1991;31:60–67.

10 Holmes JF, Ngyven H, Jacoby RC, et al. Do all patients with left costal margin injuries require radiographic evaluation of intraabdominal injury? Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:232–236.

11 Demetriades D, Karaiskakis M, Toutouzas K, et al. Pelvic fractures: epidemiology and predictors of associated abdominal injuries and outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195:1–10.

12 Iochum S, Ludig T, Walter F, et al. Imaging of diaphragmatic injury: a diagnostic challenge? Radiographics. 2002;22:S103–S116.

13 Rosen CL, Tibbles CD, Tracy JA. The use of ultrasound in trauma. In: Ernst A, Feller-Kopman DJ. Ultrasound-guided procedures and investigations: a manual for the clinician. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2006:75.

14 Boulanger BR, Brenneman FD, Kirkpatrick AW, et al. The indeterminate abdominal sonogram in multisystem blunt trauma. J Trauma. 1998;45:52–56.

15 Rozycki GS, Ballard RB, Feliciano DV, et al. Surgeon-performed ultrasound for the assessment of truncal injuries: lessons learned from 1540 patients. Ann Surg. 1998;228:557–567.

16 Farahmand N, Sirlin CB, Brown MA. Hypotensive patients with blunt abdominal trauma: performance of screening US. Emerg Radiol. 2005;235:436–443.

17 Chu UB, Clevenger FW, Imami ER, et al. The impact of selective laboratory evaluation on utilization of laboratory resources and patient care in a level-I trauma center. Am J Surg. 1996;172:558–563.

18 Keller MS, Coln CE, Trimble JA, et al. The utility of routine trauma laboratories in pediatric trauma resuscitations. Am J Surg. 2004;188:671–678.

19 Brown MA, Sirlin CB, Farahmand N, et al. Screening sonography in pregnant patients with blunt abdominal trauma. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:175–181.

20 Mackersie RC, Tiwary AD, Shackford SR, et al. Intra-abdominal injury following blunt trauma. Identifying the high-risk patient using objective risk factors. Arch Surg. 1989;124:809–813.

21 Dunham CM, Sipe EK, Peluso L. Emergency department spirometric volume and base deficit delineate risk for torso injury in stable patients. BMC Surg. 2004;4:3.

22 Davis JW, Mackersie RC, Holbrook TL, et al. Base deficit as an indicator of significant abdominal injury. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:842–844.

23 Holmes JF, Wisner DH, McGahan JP, et al. Clinical prediction rules for identifying adults at very low risk for intra-abdominal injuries after blunt trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:575–584.

24 Gelman R, Mirvis SE, Gens D. Diaphragmatic rupture due to blunt trauma: sensitivity of plain chest radiographs. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:51–57.

25 Shapiro MJ, Heiberg E, Durham RM, et al. The unreliability of CT scans and initial chest radiographs in evaluating blunt trauma induced diaphragmatic rupture. Clin Radiol. 1996;51:27–30.

26 Advanced trauma life support student course manual. 7th ed. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2004.

27 Richards JR, McGahan JP, Pali MJ, et al. Sonographic detection of blunt hepatic trauma: hemoperitoneum and parenchymal patterns of injury. J Trauma. 1999;47:1092.

28 Poletti PA, Kinkel K, Vermeulen B, et al. Blunt abdominal trauma: should US be used to detect both free fluid and organ injuries? Radiology. 2003;227:95–103.

29 Von Kuenssberg Jehle D, Stiller G, Wagner D. Sensitivity in detecting free intraperitoneal fluid with the pelvic views of the FAST exam. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:476–478.

30 Branney SW, Wolfe RE, Moore EE, et al. Quantitative sensitivity of ultrasound in detecting free intraperitoneal fluid. J Trauma. 1995;39:375–380.

31 Ma OJ, Kefer MP, Mateer JR, et al. Evaluation of hemoperitoneum using single vs multiple-view ultrasonographic examination. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:581–586.

32 Pepe PE, Mosesso VN, Falk JL. Prehospital fluid resuscitation of the patient with minor trauma. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2002;6:81–91.

33 Otomo Y, Henmi H, Mashiko K, et al. New diagnostic peritoneal lavage criteria for diagnosis of intestinal injury. J Trauma. 1998;44:991–997.

34 Bilge A, Sahin M. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. Eur J Surg. 1991;157:449–451.

35 Liu M, Lee C-H, P’eng F-K. Prospective comparison of diagnostic peritoneal lavage, computed tomography scanning, and ultrasonography for the diagnosis of blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1993;35:267–270.

36 Tayal V, Neilsen A, Jones A, et al. Accuracy of trauma ultrasound in major pelvic injury. J Trauma. 2006;61:1453–1457.

37 Fryer JP, Graham TL, Fong HM, et al. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage as an indicator for therapeutic surgery. Can J Surg. 1991;34:471–476.

38 Holmes JF, Schauer BA, Nguyen H, et al. Is definitive abdominal evaluation required in blunt trauma victims undergoing urgent extra-abdominal surgery? Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:707–711.

39 Gonzalez RP, Han M, Turk B, et al. Screening for abdominal injury prior to emergent extra-abdominal trauma surgery: a prospective study. J Trauma. 2004;57:739–741.

40 Nguyen D, Platon A, Shanmuganathan K, et al. Evaluation of a single-pass continuous whole-body 16-MDCT protocol for patients with polytrauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:3–10.

41 Salim A, Sangthong B, Martin M, et al. Whole body imaging in blunt multisystem trauma patients without obvious signs of injury. Arch Surg. 2006;141:468–475.

42 Hauser CJ, Visvikis G, Hinrichs C, et al. Prospective validation of computed tomographic screening of the thoracolumbar spine in trauma. J Trauma. 2003;55:228–235.

43 Shanmuganathan K. Multi-detector row CT imaging of blunt abdominal trauma. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2004;25:180–204.

44 Larici AR, Gotway MB, Litt HI, et al. Helical CT with sagittal and coronal reconstructions: accuracy for detection of diaphragmatic injury. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:451–457.

45 Allen TL, Cummins BF, Bonk RT, et al. Computed tomography without oral contrast solution for blunt diaphragmatic injuries in abdominal trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:253–258.

46 Killeen KL, Shanmuganathan K, Poletti PA, et al. Helical computed tomography of bowel and mesenteric injuries. J Trauma. 2001;51:26–36.

47 Janzen DL, Zwirewich CV, Breen DJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of helical CT for detection of blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:193–197.

48 Malhotra AK, Fabian TC, Katsis SB, et al. Blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries: the role of screening computed tomography. J Trauma. 2000;48:991–998.

49 Sherck J, Shatney C, Sensaki K, et al. The accuracy of computed tomography in the diagnosis of blunt small-bowel perforation. Am J Surg. 1994;168:670–675.

50 Butela ST, Federle MP, Chang PJ, et al. Performance of CT in detection of bowel injury. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:129–135.

51 Stuhlfaut JW, Soto JA, Lucey BC, et al. Blunt abdominal trauma: performance of CT without oral contrast material. Radiology. 2004;233:689–694.

52 Ilahi O, Bochicchio GV, Scalea TM. Efficacy of computed tomography in the diagnosis of pancreatic injury in adult blunt trauma patients: a single-institutional study. Am Surg. 2002;68:704–707.

53 Phelan HA, Velmahos GC, Jurkovich GJ, et al. An evaluation of multidetector computed tomography in detecting pancreatic injury: results of a multicenter AAST study. J Trauma. 2009;66:641–647.

54 Velmahos GC, Tabbara M, Gross R, et al. Blunt pancreatoduodenal injury: a multicenter study of the research consortium of New England Centers for Trauma (ReCONECT). Arch Surg. 2009;144:413–419.

55 Tsang BD, Panacek EA, Brant WE, et al. Effect of oral contrast administration for abdominal computed tomography in the evaluation of acute blunt trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30:7–13.

56 Clancy TV, Ragozzino MW, Ramshaw D, et al. Oral contrast is not necessary in the evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma by computed tomography. Am J Surg. 1993;166:680–684.

57 ACEP Clinical Policies Committee. Clinical Policies Subcommittee on Acute Blunt Abdominal Trauma: clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with acute blunt abdominal trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:278–290.

58 Stafford RE, McGonigal MD, Weigelt JA, et al. Oral contrast solution and computed tomography for blunt abdominal trauma. Arch Surg. 1999;134:622–626.

59 Cunningham MA, Tyroch AH, Kaups KL, et al. Does free fluid on abdominal computed tomographic scan after blunt trauma require laparotomy? J Trauma. 1998;4:599–602.

60 Dutton RP, Mackenzie CF, Scalea TM. Hypotensive resuscitation during active hemorrhage: impact on in-hospital mortality. J Trauma. 2002;52:1141–1146.

61 Borgman MA, Spinella PC, Perkins JG, et al. The ratio of blood products transfused affects mortality in patients receiving massive transfusion at a combat support hospital. J Trauma. 2007;63:805–813.

62 Zink KA, Sambasivan CN, Holcomb JB, et al. A high ratio of plasma and platelets to packed red blood cells in the first 6 hours of massive transfusion improves outcomes in a large multicenter study. Am J Surg. 2009;197:565–570.

63 Ozturk H, Dokucu AI, Onen A, et al. Non-operative management of isolated solid organ injuries due to blunt abdominal trauma in children: a fifteen-year experience. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2004;14:29–34.

64 Haan JM, Bochicchio GV, Kramer N, et al. Non-operative management of blunt splenic injury: a 5-year experience. J Trauma. 2005;58:492–498.

65 Velmahos GC, Toutouzas KG, Radin R, et al. Non-operative treatment of blunt injury to solid abdominal organs: a prospective study. Arch Surg. 2003;138:844–851.

66 Wallis A, Kelly MD, Jones L. Angiography and embolisation for solid abdominal organ injury in adults—a current perspective. World J Emerg Surg. 2010;5:18.

67 Wahl WL, Ahrns KS, Chen S, et al. Blunt splenic injury: operation versus angiographic embolization. Surgery. 2004;136:891–899.

68 van der Vlies CH, van Delden OM, Punt BJ, et al. Literature review of the role of ultrasound, computed tomography, and transcatheter arterial embolization for the treatment of traumatic splenic injuries. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:1079–1087.