CHAPTER 33 Blepharoplasty in the East Asian patient

*The figures in this chapter represent original artwork prepared by the author.

Introduction

A major problem here is that surgical “Westernization” really doesn’t work on an Asian face with an Asian skeleton. The outcome typically looks neither Western nor East Asian, and the one who opted for it ends up feeling alienated from both cultures. For this reason it is prudent to discourage loss of one’s ethnic integrity,1 especially doing blepharoplasty, where lid fold creation and placement, and medial epicanthoplasty maneuvers, are essentially irreversible.

Understand also that the aesthetics of Asian blepharoplasty encompass far more than the creation of lid folds on upper eyelids.2

The history of Asian periorbital surgery

• The first description of Asian upper lid surgery done solely for aesthetic purposes was in 1896, in Japan, by Dr. K. Mikamo.3 His technique involved three braided silk sutures, placed transdermally, grasping a small purchase of conjunctiva, and then exiting. The sutures were then ligated and left 2–6 days before removing.

• A more well-known early description of the suture technique was published in 1926 by Dr. Kozo Uchida,4 who reported on 1523 patients. He used three sutures of catgut, with knots buried beneath the skin.

• Three years later, in 1929, the first incisional technique was reported in Japan, also using catgut. This report appeared in the Japanese Journal of Clinical Ophthalmology, authored by Dr. M. Maruo.5 Many other operative descriptions appeared in Japanese journals between Dr. Maruo’s article and the first “known” English publications on the subject of Asian eyelid surgery.

• The increased Western presence in Japan and the Philippine Islands in the aftermath of the World War II, in Korea beginning in the 1950s, and in Southeast Asia thereafter, led to a misunderstanding – both by local surgeons and by Western surgeons – of the desires and intentions of those requesting Asian lid fold procedures. “Westernization” was somehow substituted for a subtle desire to enhance natural Asian beauty in a population that poorly understood the anatomical differences, and to what degree these differences were capable of impacting a person’s life. The lid configuration most desired was one that actually occurred naturally in many East Asian eyes – a small pretarsal segment with the crease running parallel to the lash line centrally and laterally but migrating progressively closer to the lid margin nasally. The smaller epicanthal canopies were also preferred.

• The goal distortion was aided by Dr. Ralph Millard’s report, which was the first one on Asian eyelid surgery that was widely distributed in the English language, “Oriental Peregrinations:” with a subsection entitled, “Oriental to Occidental.” It appeared in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery in 1955.6 In this article Dr. Millard emphasized “Westernization” to a huge English speaking population, while the many earlier Asian surgeons, who also advocated “Westernization”, did so to a far more restricted audience.

• The other two early English essays on the subject were by Dr. Sayoc7 in 1954, who sutured the dermis of a pretarsal incision to the anterior aspect of the tarsus, and Dr. Fernandez from Hawaii in 1960, whose publication entitled, “The double eyelid operation in the Oriental in Hawaii”,8 became the world standard for open technique, and remains popular to this day. It was this operation that the senior author first learned, expanding it into his own more precise (“Flowers”) technique, which itself is widely used today.9 In 1993 the senior author worked closely with Dr. Fernandez, re-drawing his illustrations for anatomical clarity and more accurately describing his “landmark” operation, which then appeared in that year’s April issue of Clinics in Plastic Surgery (which Flowers himself edited).10

• Credit for the splendid split V-W medial epicanthoplasty (Fig. 33.1) belongs to Dr. Junichi Uchida.11 But his “W” scars were unnecessarily large, and he usually connected the upper limb of his lid fold incision with the upper aspect of the W, which rotated the nasal extension of the lid fold too far above the lid margin, “Westernizing” the eye unnecessarily and well beyond contours that occur naturally in Asians. This operation also encouraged deforming contractures with an incision encircling the medial canthus.

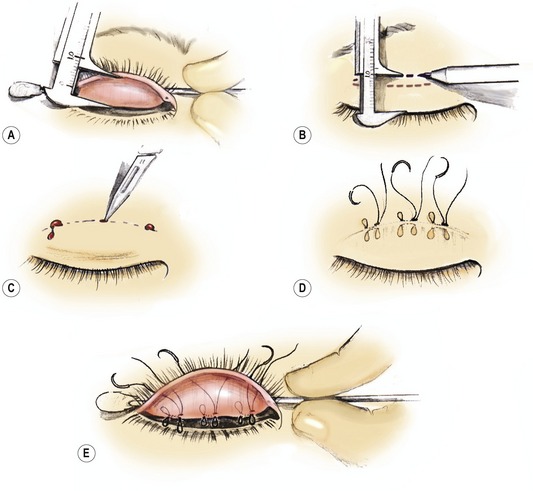

• The senior author (Flowers) modified and solved these problems by simply reducing the size of the W, keeping the upper limb of the W well above the medial extent of the lid fold, or lid fold incision, and suturing more meticulously12 (Figs 33.2, 33.3), emphasizing also the meticulous placement and removal of the tiny epicanthoplasty sutures – avoiding wound disruption and secondary healing.

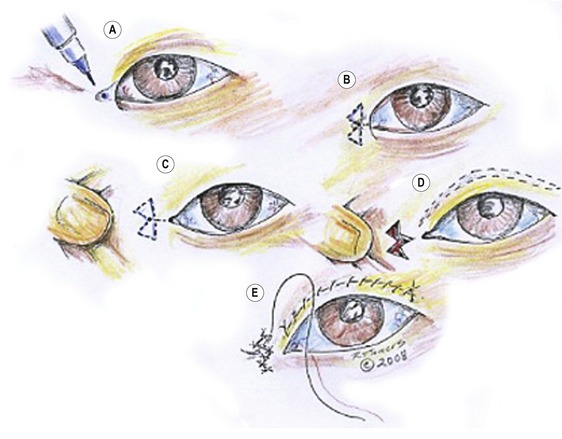

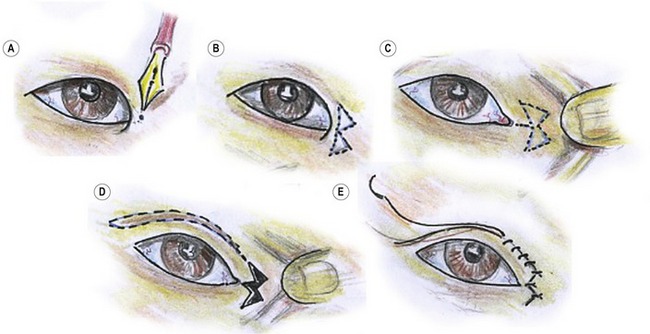

Fig. 33.2 Flowers’ modification of Uchida medial epicanthoplasty. A, Mark the key point of the epicanthoplasty 0.5 mm lateral to the desired medial extension of the inner canthus. B, The marked point in A becomes the apex of the center of the W. C, Pull the skin nasally so the W excision can be marked – usually to include the little extra skin between the two triangles. Keep the W as small as is feasible. D, Excise the joined triangle, within the W and split skin (the V) right down to the epicanthus. E, Closure of the epicanthal incisions (see Fig. 33.3). The difference between this and the Uchida’s procedure is the small W and the fact that the medial extent of the crease incision always falls well beneath the superior limb of the W, for a more natural Asian look.

The split V-W medial epicanthoplasty is far superior, less deforming, and has much less scarring than the Mustardé “stick figure”(jumping man) or the many other Z-plasty modification epicanthoplasty.13 Lots of other techniques attempt to solve the prominent medial epicanthal canopy, but the authors found none with benefits that exceed those of the split V-W-plasty.

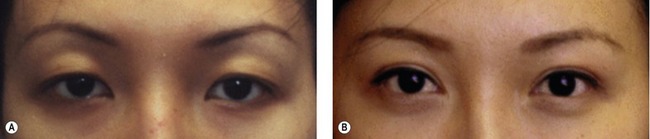

Creating a lid fold is not the most challenging aspect of Asian lid surgery. Symmetry, grace, accuracy and naturalness are far more important, and more difficult to achieve (Fig. 33.4). These aspects of Asian lid surgery were introduced, and stressed repeatedly over the last 35 years by Flowers.14,15 Minor adjustments were defined, clarified and refined.

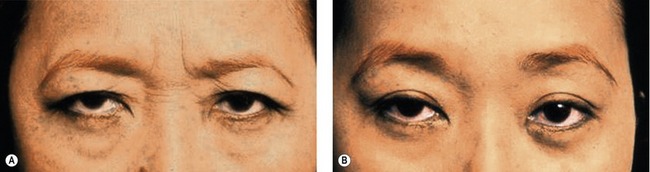

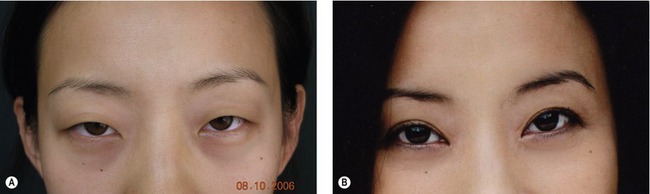

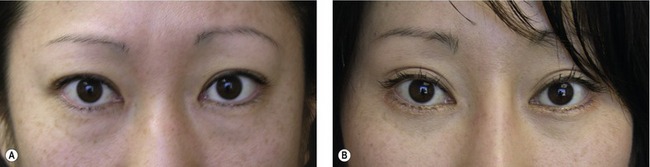

Flowers also pointed out the importance of combining frontal lift with lid fold procedures for most females over 30 years of age (Fig. 33.5), or simply substituting a brow elevation operation for lid surgery16 when precise lid folds exist, but are hidden by a droopy brow with overhanging lid tissue17 (Fig. 33.6).

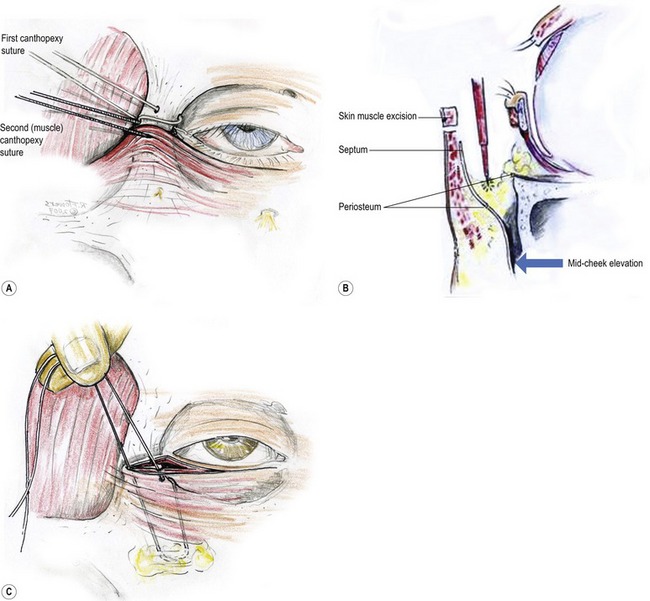

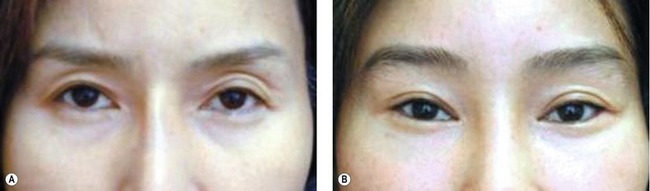

Also emphasized by the senior author in his many graduate courses on Asian lid surgery was the repair of lid ptosis simultaneous with lid fold creation. Precise measuring techniques and adjustments were developed to ensure symmetry of the pretarsal skin segments (most commonly caused by brow asymmetry) – plus the recognition of prominent globes on one, or both sides, and how to lend symmetry to repair in their presence. Flowers also stressed the importance of a new type of lower lid repair that eliminates scleral show and restores lower lid posture and tilt, both in primary and secondary eyelid procedures18 (Fig. 33.7). Fig. 33.7A shows the components of the two-layered canthopexy so effective in restoring youthfulness, and correcting the iatrogenic, developmental, and traumatic deformities.

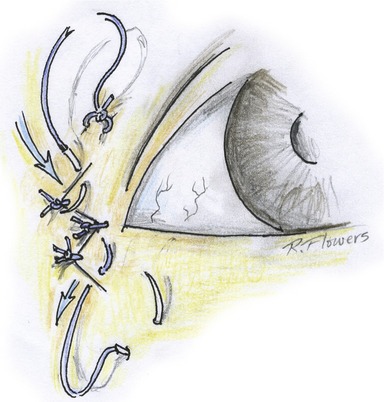

Fig. 33.7 A, The two-layered canthopexy corrects the lower lid and retinacular laxity and atonicity. The first layer, the lateral canthal tendon and retinacular tissue are secured into a drilled hole in the orbital rim, exiting at its anterior medial aspect. The second layer of orbicularis muscle flap and other adherent tissues is sutured to the bone rather than pulled “into” the orbital rim. B, Note the release of arcus marginalis, and periosteum which allows the second layer of the canthopexy to include periosteum, orbital septum, fat, orbicularis, cheek fat, and skin. This second layer of the canthopexy serves as a magnificent midcheek lift, and often garners additional support from an absorbable suture, securing it to a drilled hole. C, Connecting the malar fibrofatty tissue and periosteum into a drill hole in the lower lateral orbital rim.

Anatomy and physical evaluation

Unique anatomical characteristics of East Asian eyelids

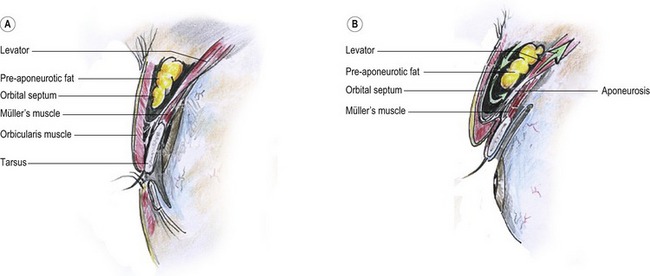

For years it was thought that supratarsal creases formed as a result of fibers from the aponeurosis continuing into the muscle or perhaps even into the dermis. Although commonly described, there is little evidence that they actually exist as proven entities. Lid creases consistently form precisely at the lowest point of the septo-aponeurotic sling’s descent into the lid.19 This sling is created by the (often delicate) fusion of the orbital septum with the aponeurosis (Fig. 33.8A), while the pre-aponeurosis fat is acting rather like a “ball bearing.”

Fig. 33.8 A, The septo-aponeurotic sling. The aponeurosis joins with the orbital septum at variable levels, creating a sling that contains the orbital fat. The level that this sling descends into the lid defines where the lid fold forms. B, When the levator muscle retracts, the sling rolls inward and upward, with the pre-aponeurosis fat acting rather like a “ball bearing”.

When the levator muscle retracts (Fig. 33.8B), the sling rolls inward and upward. The orbicularis is, without question, adherent to the orbital septum (with or without the theoretic “fibers”), and this causes the orbicularis to invaginate upon eye opening – with that same adherence as when the same septo-aponeurotic sling rolls inward and upward.

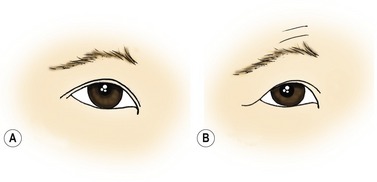

This characteristic makes it easy to discern East Asian from non-Asians in a simple sketch by simply placing the eyebrows high above the eyes (Fig. 33.9).

Double eye is the common term used in Asian communities for an upper eyelid showing a dominant crease in its lower aspect, along with it at least a little visible pre-tarsal (or sub-lid-fold) skin, if only in the lateral portion of the eyelid (Fig. 33.10). Not infrequently there will be a well-defined lid fold on one side, while minimal to no crease may be visible on the other.

It is not uncommon for even youthful East Asians, to have such precipitous drops in eyebrow position after upper lid excision and/or invagination (lid fold creation), that they require simultaneous (or deferred) forehead or brow lifts. The condition responsible for this is known as compensated brow ptosis,20 a term devised and popularized by the senior author. Compensated brow ptosis is the very common condition where the resting level of the eyebrows is so ptotic and low that it interferes with unobstructed forward vision, especially laterally, thereby forcing the frontalis muscles into constant contraction in order to see. Because the frontalis usually inserts mainly into the medial brow, the overhang that most needs correcting is usually lateral aspect. The medial brow overcorrects in its attempt to clear the lateral brow overhang. The frontalis muscles are forced to contract for 16–18 hours a day without relaxing.

Some patients with lid folds hidden beneath overhanging eyelid and brow skin require only frontal lifts to reclaim, or display for the first time, lovely natural lid creases, or “double eyelids” (Fig. 33.11). The “gift” is received without the swelling and other early postoperative morbidities seen with invasive lid invagination surgery (see also Fig. 33.26).

The desirability of lid folds (“double” eyes)

There is a preference in most Asian cultures for a distinct lid crease, residing one to four millimeters above the lash line, extending slightly beyond the lateral canthus (Fig. 33.12). Rarely ladies prefer it even higher. It replicates the pleasant curvature of the upper lid margin, and in so doing confers an illusion of a larger, longer eye. But the crease’s characteristics must resemble those that occur naturally in Asians, meaning it moves progressively closer to the lid margin along the medial third of the eyelid.

Over the millennia, Asian artists and sculptors have often chosen “double” eyelids to magnify beauty within the objects of their creativity. Even today millions of young and not so young Asians – all potential blepharoplasty patients – spend as much as an hour and a half each morning applying intricate combinations of transparent tape and heavy mascara in ways that force a lid crease to form. Sometimes skin glue or adhesive produces a similar effect, but this method carries with it a rather bizarre lagophthalmos on blinking. The technique persists only because the person hosting the phenomenon is blinded by the “blink” and doesn’t see the deformity.

Sometimes the slender-slit or pseudo-blepharoptotic eye carries with it such delicate grace and submissive beauty, creating such a magnificent work of art – that it begs to remain undisturbed. In other persons a similar lid may suggest a “sinister” aura, which can be extremely restrictive socially and professionally. There is an ancient Chinese adage suggesting that one should never trust a person with slender-slit narrow fissure type eyes. Generally such an Asian characteristics (Fig. 33.13) yield in desirability to the more “open” and “accessible” appearance of a naturally occurring, or skillfully created, “double” eye.

Natural and unnatural Asian lid folds

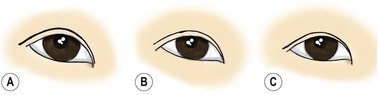

When lid folds occur naturally in East Asian eyelids, they have physical characteristics which differ from those occurring in other populations.21 In the youthful East Asian a natural fold typically parallels the lid margin in the outer two-thirds of the eyelid, closing towards the eyelid margin as it proceeds nasally. Medially, the crease may either end just above the epicanthal canopy (usually preferable) (Fig. 33.14A), extend to its medial margin (Fig. 33.14B), or dive beneath the epicanthal canopy (Fig. 33.14C). Sometimes, in Asians with prominent noses, and occasionally in those without, there may be no epicanthal canopy or epicanthus at all.

In Western and other non-Asian eyes the lid folds commonly parallel the lid margins all the way across the eyelid, but often move further away from the lid margins nasally, exposing more pretarsal skin. The latter rarely occur naturally on youthful East Asians, but sometimes the “crease”, especially when very close to the Asian lid margin, will parallel the lash line (Fig. 33.15A). The one situation where we see Asian lids with taller pre-tarsal segments nasally is after bad surgery or where there is a natural lid crease with a once fully visualized pretarsal component, but which is no longer exposed laterally (because of years of progressive scalp and forehead stretching). This causes an increased response activity in the frontalis muscle which usually inserts predominantly into the medial brow (Fig. 33.16).

Fig. 33.15 A, Another type of natural fold where a crease of very small height parallels the lid margin throughout its length. B, As the brow drops with age, the responding frontalis muscle raises the medial brow more in its quest to clear the lateral overhang. (See Fig. 33.16 for the typical origin of the frontalis muscle.)

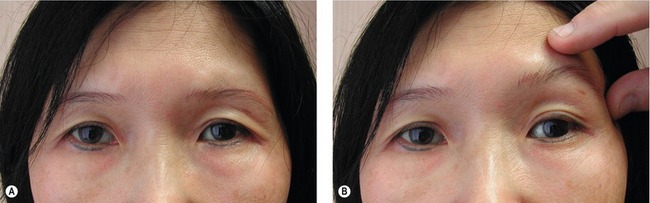

In its attempt to raise lateral brow overhang, because of its medial brow insertion, it must overcorrect medially, and in so doing exposes a lot more pretarsal skin nasally than laterally (Fig. 33.15B). With overhang decreasing the visualized lateral pretarsal skin, an unnatural un-Asian appearance evolves, which also has an older appearance, in an area that could be a focus of attractiveness. Figure 33.17 shows a modest deformity of this type. Manual elevation of the left brow emphasizes how correction lies not in an eyelid operation (which would only worsen the condition), but with lateral brow position restoration, which cancels the muscle’s need to overcorrect, it frees the medial brow to drop into a more natural resting position.

Technical steps

Choosing the best operation for each patient

1. Correcting asymmetry

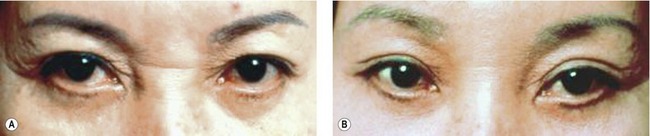

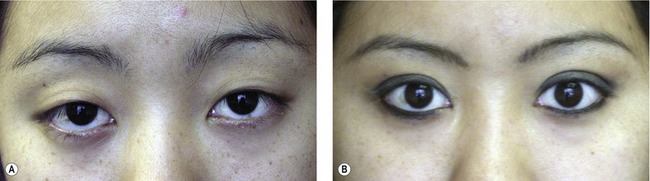

Consistent success in releasing the beauty and charm of Asian eyes means we must modify each operation to reduce any illusion of asymmetry, the most common cause of which is asymmetrical brow ptosis. Next is the amount of globe exposed. Not far behind comes the height of the upper lid pretarsal skin segment. Inequality of this segment, whether due to asymmetry of brow posture or eyelid ptosis (or retraction)*, often becomes apparent only after Asian blepharoplasty or a frontal lift exposes the pretarsal part of the eyelid, which had previously been concealed by the “single” eye with the lid overhang (Fig. 33.18).

As mentioned above, the most common sources of lid asymmetry are: (1) a difference in brow position; followed by (2) inequality of globe exposure; (3) orbital position; (4) lateral canthus; and (5) lower lid postures. Globe exposure can only be mentioned briefly here, and that is only to urge that we not let its cause be iatrogenic! (Fig. 33.19).

Fig. 33.19 Postoperative double lid asymmetry, caused one globe being more prominent than the other with the surgeon not taking this into consideration when planning and executing the operation.

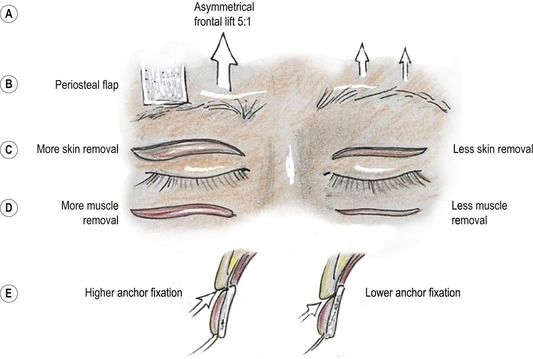

Brow asymmetry and/or unilateral lid ptosis (or retraction) are behind most upper lid asymmetry. When one brow is lower (as it is most of the time) juxta-brow and eyelid tissue on the lower side drops down to overhang the pretarsal segment. If no brow positioning procedure is to accompany, pretarsal symmetry remains within reach by removing a little more skin and muscle from the side with the lower brow, as well as designing the pretarsal skin component a little taller and attaching it a little higher onto the anterior tarsus and/or aponeurosis (Fig. 33.20). If scalp excision or a frontal lift is part of the surgical plan, add a maximal superio-lateral resection on the lower side, and reduce scalp resection or advancement on the higher side by  to 5 times the millimeter amount of pre-existing brow position difference, measured and backed off from the point where the same advancement force is applied to the second side of the scalp as was applied to the first. We resect nothing from the central scalp on the higher side, but remove

to 5 times the millimeter amount of pre-existing brow position difference, measured and backed off from the point where the same advancement force is applied to the second side of the scalp as was applied to the first. We resect nothing from the central scalp on the higher side, but remove  times the pre-existing medial brow difference centrally on the lower side. This markedly improves positional brow asymmetry. If one side is exceptionally low, or unexpectedly remains somewhat lower after attempting to correct the asymmetry with an asymmetrical frontal lift, then complete the compensation for pretarsal asymmetry with either a superiorly based periosteal flap (Fig. 33.21), or modest applications of increased skin and muscle excision and increased pretarsal skin height, directed to the smaller side, which should complete the quest of symmetry. However, this requires Asian blepharoplasty to accompany operation.

times the pre-existing medial brow difference centrally on the lower side. This markedly improves positional brow asymmetry. If one side is exceptionally low, or unexpectedly remains somewhat lower after attempting to correct the asymmetry with an asymmetrical frontal lift, then complete the compensation for pretarsal asymmetry with either a superiorly based periosteal flap (Fig. 33.21), or modest applications of increased skin and muscle excision and increased pretarsal skin height, directed to the smaller side, which should complete the quest of symmetry. However, this requires Asian blepharoplasty to accompany operation.

Fig. 33.20 Different way to correct eyelid asymmetry due to asymmetrical brow position. A, Asymmetrical frontal lift. B, Insert a superiorly based periosteal flap into the junction of the middle and lateral thirds of the brow which is lower (see Fig. 33.21). C, Excise more lid skin on the side of the lower brow. D, Excise more muscle (along with more skin) on the side of the lower brow. E, Make the pretarsal skin segment taller on the side of the lower brow, and anchor it at the higher level into the tarsus or the aponeurosis or both.

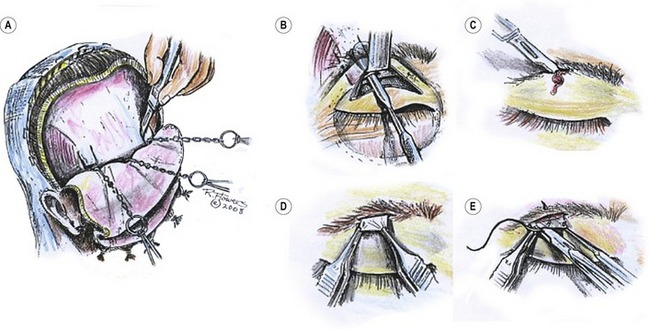

Fig. 33.21 Superiorly-based periosteal flap mentioned in Fig. 33.20. A, Creating 2 cm wide superiorly-based periosteal flaps to assist the correction of severe brow ptosis. B, Same procedure carried out via upper blepharoplasty approach. C, Incision made at the junction of the middle and lateral thirds of the eyebrow. D, Adjust tension and position of the flap. E, Secure the flap to the deep brow with three interrupted sutures, trimming the periosteal so that it falls within the brow. The flap may be sutured either with skin sutures only, or the flap may be secured deeper with interrupted absorbable sutures (also placed parallel to avoid follicle injury).

Ancillary procedure to further lift the lateral brow

Carefully incise and elevate a 2 cm wide, superiorly-based periosteal flap with the lateral borders just barely overlapping the temporal crest (Fig. 33.21). The access routes are most commonly through a large flap frontal (coronal) lift. Sometimes, when a large flap is not feasible an alternative choice is through upper lid blepharoplasty incision, widely undermining just above the periosteum. Make the incision in the brow at the junction of its middle and lateral thirds, protecting and preserving the eyebrows by cuts that parallel the follicles. Make a tunnel through the brow by blunt dissection in a beveled fashion; deliver the periosteal flaps through the openings. Suture the flap into the deep brow, adjusting the tension as appropriate. This technique is very effective in achieving symmetry when one brow is significantly lower than the other.

2. Medial epicanthal folds

Success in Asian blepharoplasty also means that we must make optimal aesthetic decisions on whether to modify the epicanthal folds, if present22 (Fig. 33.22).

• If the folds are prominent and create even the slightest hint of telecanthus or internal strabismus.

• If there is an epicanthus inversus with the free border of the canopy turning laterally onto the lower eyelid (Type III) – especially the larger variety. Also treat pseudo I or Type IV epicanthus the same way. On initial inspection it resembles Type I, the more Western looking eye, but it is indeed a tight canopy type epicanthus that must be treated as a large Type III.

• If the lid crease by design dives beneath the epicanthal canopy as it moves medially.

• If loose skin abounds around the inner canthus in Asian ladies above 45 years of age, no matter how small the epicanthal canopy might be. If the character or prominence of the medial epicanthus calls attention to itself, or in any other way distracts from the contour of the lid and lid fold, then do a medial epicanthoplasty.

• When attempting to make an “outside” fold without releasing the epicanthus results in an undesirable extra crease traversing the pretarsal skin, running diagonally, from lateral to medial, ending up near the inner canthus.

In Fig. 33.2 we lay out our preferred technique, the Flowers modification of the old Uchida medial-epicanthoplasty. We keep the W limb dimensions as tiny as possible ( to 2 mm up to as long as

to 2 mm up to as long as  to 4 mm for unusually large epicanthus), making sure that the upper limb of the “W” is always well above the medial extent of the upper lid incision. This avoids a scar contracture recreating the epicanthus we are working so hard to eliminate.

to 4 mm for unusually large epicanthus), making sure that the upper limb of the “W” is always well above the medial extent of the upper lid incision. This avoids a scar contracture recreating the epicanthus we are working so hard to eliminate.

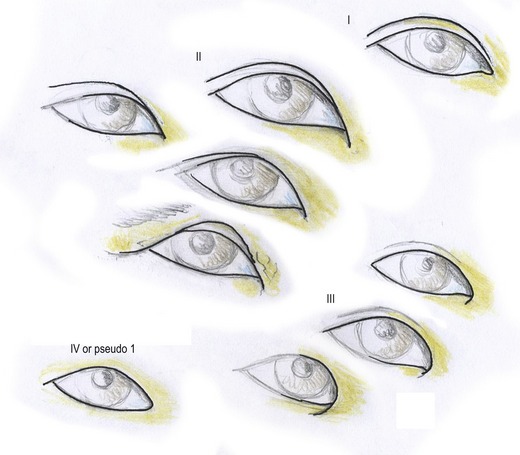

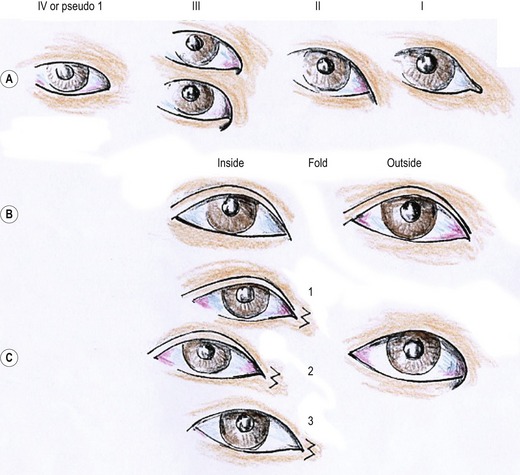

Most of Fig. 33.23 is redundant, but aspects of it clarify important issues. Fig. 33.23A classifies the different types of medial epicanthal folds seen in Asian eyes, while Fig. 33.23B describes the two preferred types occurring naturally in Asian eyes, and Fig. 33.23C the medial epicanthal options available with the most exaggerated medial epicanthi – the large epicanthus inversus. The following text clarifies these matters, relating closely to this illustration.

• The first, in Fig. 33.23A, is Type I, the Asian variant that most resembles a Western eye.

• Type II has a canopy that angles down diagonally from the inner corner of the eye. It may vary in size and prominence. We prefer medial epicanthoplasties with most of these, although it is optional with the smaller variety.

• Type III is called epicanthus inversus, with the epicanthal canopy curving all the way around the corner, angling back laterally. Beneath III we see the smaller as well as the larger variety of this epicanthus. We prefer medial epicanthoplasties in most all Type IIIs, but especially in the larger ones that give the illusion of esotropia or internal strabismus, even when no lid folds are created or desired (see the possible variations in Fig. 33.23C).

• Type IV is an enigma, often masquerading as Type I, and we sometimes refer to it as Pseudo Type I. There are no visible edges, like in IIs and IIIs, but it nevertheless represents a tight band of skin that wraps around the medial corner – with the caruncle being 3–4 mm beneath the tethering epicanthal canopy. Don’t miss the opportunity of correcting this with a split V-W medial epicanthoplasty.

• Fig. 33.23B shows the most popular lid fold contour for Asian eyes. Some request folds that parallel the lid margin across the entire lid. This works well if the fold is quite minimal in height, but a tall parallel fold strips away the “Asian-ness” of the eye. Recognize that other lids show the pretarsal skin only in the lateral lid (see Fig. 33.10).

• Fig. 33.23C shows the different ways our modifications of the Uchida epicanthoplasty can beautify the Asian eye, (1) either by creating an “outside” fold; or (2) creating an inside fold, that dives beneath the epicanthus inversus at, or near, the corner); or (3) by modifying the prominent epicanthus inversus without creating a lid fold.

3. Making Asian eyelids more attractive with frontal lifts

A superb way to emphasize, rejuvenate or restore one’s natural Asian eye characteristics and avoid any suggestion of surgical alteration is to reposition the brow with a frontal lift procedure. It freshens and rejuvenates appearance, and emphasizes or re-emphasizes the naturally existing lid creases or folds which are often present, but in hiding. It also restores lid folds that were beautifully created decades in the past that gradually disappeared with brow descent. Its main use in Asians is for people between 25 and 55 in whom the mid and upper face need help, but the patient (unlike Caucasians) is not yet ready for a facelift. It is now a near routine part of the Asian eye surgical plan, either to restore youthful anatomy or to check or limit the profound brow drop that commonly occurs after Asian blepharoplasty (Fig. 33.24).

It can also prove extremely beneficial to twenty year-olds, or even to teenagers who have profoundly low resting levels of their eyebrows with a lot of frontalis activated compensated brow ptosis brow elevation.23

Sometimes the frontal lift’s task is simply to clean up a single eye in middle years or beyond, without creating or even restoring a lid fold. The lift’s lateral emphasis brow elevation commonly “de-stresses” the exaggerated frontalis action on the medial brow (driven by visual field compromising lateral overhang), allowing the medial brow to drop to a more restful and aesthetically pleasing position (Fig. 33.25).

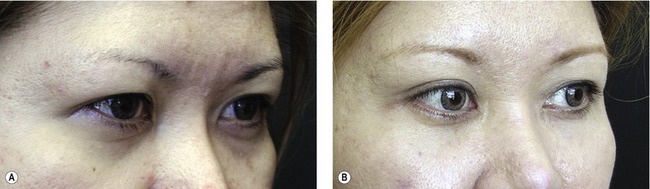

The key to success in frontal lifting is resecting (or advancing) the superior-lateral portions of the scalp flap, with little to nothing removed or advanced centrally (except as recommended above to correct brow asymmetry). Notice in Fig. 33.26 the restoration from only a coronal lift and a small medial epicanthoplasty with neither blepharoplasty nor lid-fold procedure.

The operation is very effective, but be attentive to hollowed out upper lids. Isolated frontal lifts have a tendency to increase visibility of the lid hollows. But instead of deleting the coronal lift, consider diminishing the hollowed effect by combining a secure canthopexy-midface lift with the coronal. This tightens the lax lower lid structures, adding fullness to the upper lid. We call this the Mag-5 (Fig. 33.27).

4. Lid fold creation for Asian eyelid

Although variations abound, there are essentially three basic techniques for surgical lid fold creation: the open “anchor”, or invagination blepharoplasty; the closed “suture” method; and a “half-open” effect. All of these operations usually generate a profound drop in the resting posture of the eyebrow (Fig. 33.28).

Open method

Figure 33.29 depicts planning the open anchor method we developed in 1970 and have been using regularly since 1972 on most Asian patients. It is popular in both America and Asia. The procedure has remained much the same over the years, except for our having shortened the vertical height of the pretarsal skin segment since its original description. Surgeons who know the operation find it highly effective in producing predictably high quality aesthetic results that last indefinitely. We know of no lid folds of our own that have failed, although some have become obscured by brow descent with age. We have restored many of those with a frontal lift, often combined with a youth restoring canthopexy extended to include midfacial lifting.

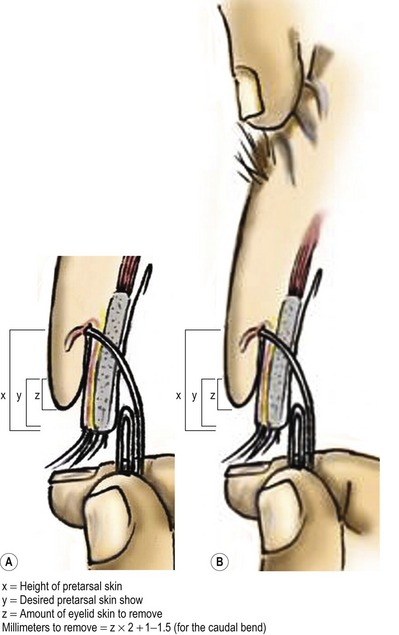

In order to precisely target the amount of eyelid skin, if any, that we need to remove to get the desired result, you can use the following steps (Fig. 33.29), or you can proceed by estimation. Position the curved wire on the upper lid surface at the level of the desired crease or lid fold. With the eye open, invaginate the skin to that level gently so the natural open-eye position of the eyelid margin is not raised. With the other brow securely elevated with a finger, and the contralateral lid tucked in with the paper clip, unobstructed open eye vision should be possible with a now fully relaxed frontalis muscle. This allows the eyebrow to descend to its natural resting level (since there is no brow elevation triggered by obstruction to forward vision). With the brow thus relaxed, measure how much overhang must be reduced to expose the desired height of pretarsal skin.

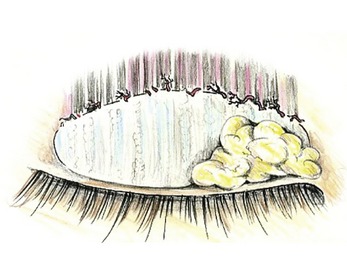

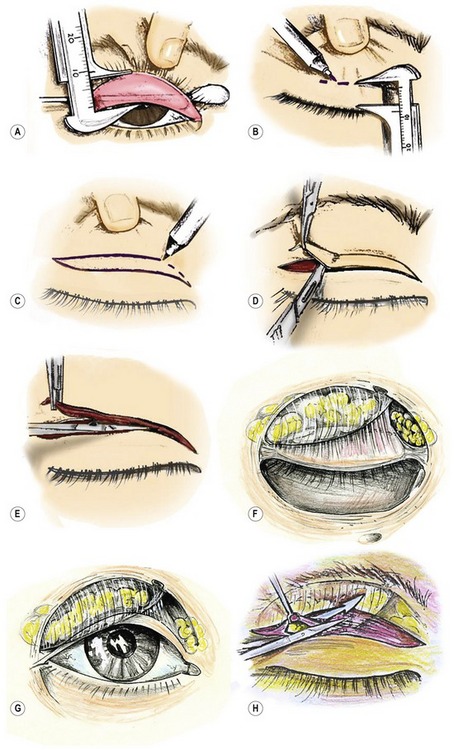

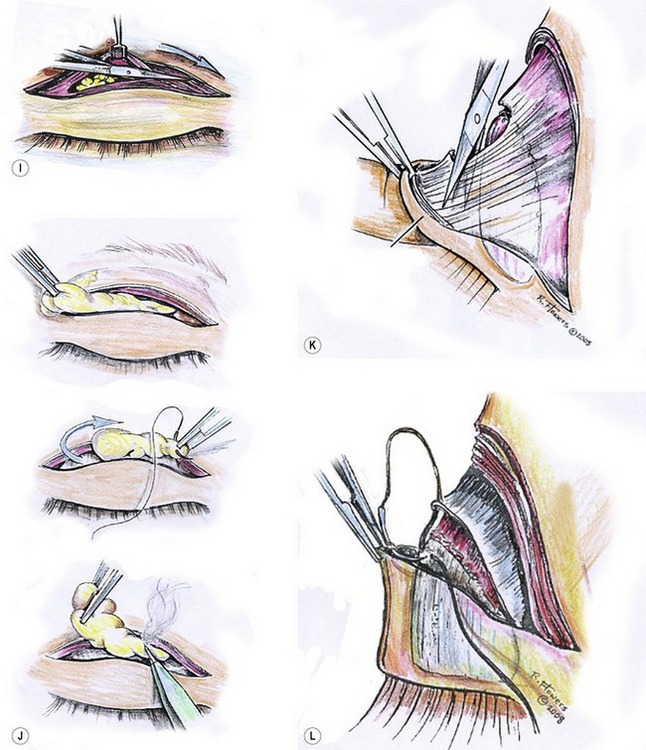

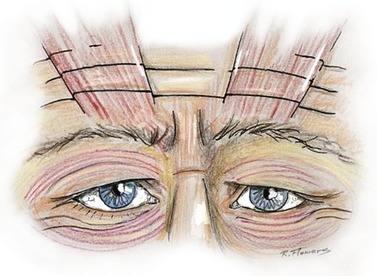

The initial steps are shown in Fig. 33.30A–E. Figures 33.30F and G provide excellent views of the septo-aponeurotic sling that houses the orbital fat. Note especially how the caudal aspect of the sling parallels the upper lid margin -not in the closed position, but in the open position.

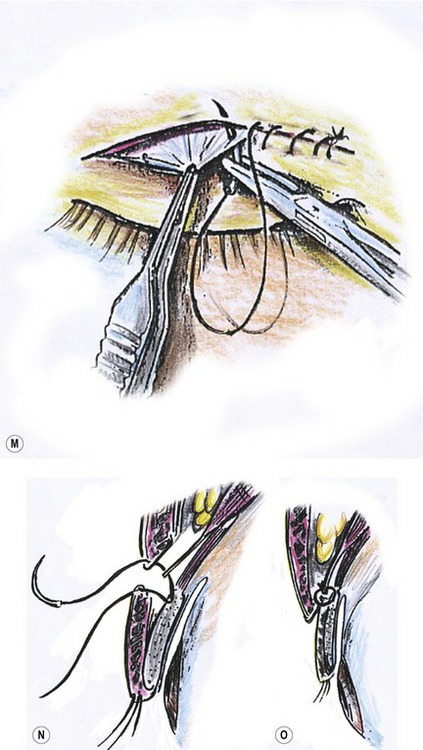

Fig. 33.30 A, At the beginning of the operation, turn the lid over and measure the tarsus. B, With the skin under uniform tension, mark the lower skin incision with a Jameson caliper: 8 to 9 mm above the lashes for a 4 mm tall pretarsal segment, 8 mm for a 2.5–3 mm segment, and 7 mm for a 1.5–2 mm pretarsal segment. The 2 mm added by including the lashes and lid margin compensate for the tightly stretched skin and the inward curvature necessary to reach the anterior tarsus. C, Mark the upper skin incision on the information assessed preoperatively (see Fig. 33.29). The incision should be kept within the orbital rim and the actual lid creasing. D, Skin excision occurs separately from the orbicularis muscle excision. E, Next, remove a sliver of orbicularis muscle carefully. Never tent this up during excision for fear of inadvertently transecting the aponeurosis. F, The septo-aponeurosis sling that is housing the orbital fat descends lower laterally and migrates cephalad nasally. If this direction of the sling is not appreciated, an attempt to open the septum across the lid may sever the aponeurosis instead. G, The configuration of this sling parallels the eye in the open not the closed-posture. H, Because the septo-aponeurotic sling that houses the orbital fat descends lowest laterally, that is the point where the orbital septum is most safely entered and the sling opened. Apply slight pressure on the globe to force the orbital fat bulge, and its characteristic appearance indicates the correct space. This step requires an understanding of the anatomy of the “sling” in order to avoid accidental sectioning of the aponeurosis (see Fig. 33.30 F,G). After entering the septum, the scissors must be angled cephalad, cutting from lateral to medial. Note that the caudal margin of this sling parallels the lid margin of the open eye in the lateral two-thirds of the lid. I, At the junction of the lateral two-thirds and medial thirds of the lid, change to a slightly caudal angulation, continuing the cut through the superficial slip of the septum, across the lid towards the medial canthus. This separates septum from aponeurosis across the lid without injuring key structures. J1, Fat excision is quite simple with the orbital septum open across the lid, but take care that its ease of access does not lead to excessive reduction. J2, There is often a prominent tuft of lateral orbital fat tucked behind the orbital rim, next to the lacrimal gland. This fat may be excised, or it may be transposed into the hollow defect. J3, Carefully secure hemostasis for the vascular mesentery of the fat, as well as all entering vessels. K, With the pretarsal skin flap turned downward over a finger; transect the aponeurosis down to the tarsus with scissors sliding along the tarsus surface just above the level of the lash bulbs. There are multiple layers to cut through before the bare tarsus emerges. Prepare the platform for fixation by removal of the filmy pretarsal connective tissue. In Asians, expect more pretarsal fatty tissue, especially over the medial tarsus. Remove fat and pretarsal orbicularis muscle, leaving less tissue to become postoperatively edematous. This encourages better fixation and a flat smooth somewhat stylized pretarsal skin surface. L, Anchoring stitches. Use 6-0 Vicryl suture to attach the dermis of the pretarsal skin flap to the anterior superior aspect of the tarsus and to the free edge of the aponeurosis. Ask the patient to close and open eyes to adjust the placement of this suture at a sufficient which only to smooth out the pretarsal skin, but not evert the lashes. Laterally, where the tarsus begins to dwindle in height, the suture(s) join only the aponeurosis to the dermis. M,N,O, Skin closure with 6-0 Prolene incorporates the edge of the aponeurosis into the suture closure across the lid.

Always be cautious to open the septum in a way that preserves maximum length of the aponeurosis (Fig. 33.30H&I), or at least of the septo-aponeurotic extension thereof,24 to assure a proper connection without creating lid retraction. Modify the orbital fat as appropriate (Fig. 33.30J).

Prominent eyes are predisposed to lateral upper lid retraction, and unfortunately, prominent eyes are frequent companions of shallow Asian orbits with prominent eyes. Such patients are safer candidates for a “closed” or “half open” repair.25

In the actual anchor-invagination technique, often sectioning the pretarsal extension of the aponeurosis as low as possible (Fig. 33.30K). use a 6-0 Vicryl on a tapered needle to create a union between skin, tarsus and aponeurosis (Fig. 33.30L). The tarsal attachment adds an extra secure anchor, which also checks against lash eversion, a common problem after lid fold procedures.

The dermal connection to the aponeurosis keeps the pretarsal skin taut. Laterally, where the tarsus dwindles in vertical height, attach the aponeurosis only to the dermis of the pretarsal skin flap, similar to the basic technique proposed by Dr. Fernandez in 1960. For skin closure, incorporate the edge of the aponeurosis into the skin repair (Fig. 33.30 M,N,O), preferably with a non-absorbable 6-0 Nylon or Prolene on a tapered needle.

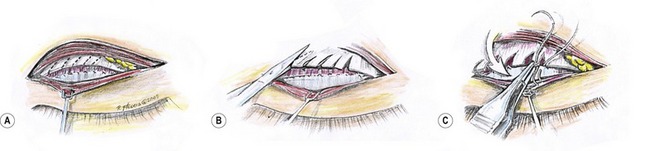

Closed (suture) method

Occasionally “closed” or suture methods work superbly well. This is especially true with very thin eyelids with minimal fat. It is a meaningful alternative when operating on people with prominent eyes. Figure 33.31 shows our preferred technique very clearly. Figure 33.1A: First measure the vertical height of the tarsus; then, Fig. 33.1B: delineate where the desired folds are to be located (The paper clip technique described in Fig. 33.29 is valid here also, although there will be no skin removal). Figure 33.1C: With a scalpel make small incisions for three to four “through and through” 6-0 to 7-0 permanent sutures usually placed at, or near the top of the tarsus, (sometimes 2–3 mm lower, in which case the suture transgresses the tarsus itself). In doing so the permanent buried suture runs a risk of irritating the cornea. Fortunately it usually develops a trough that prevents corneal irritation. Sutures within the substance of the tarsus could contribute to chalazion formation. The sutures run beneath the conjunctiva on the deep side and beneath the skin on the anterior surface (Fig. 33.1D&E). The knots of the suture ligation sink into the lid tissue and a single suture closes the tiny wound. Absorbable suture also works reasonably well for this technique. The main problem however with closed repair is the lack of longevity in holding capacity.

Simple skin excision in Asian upper lids

Persons with no folds, and who wish none, may have too much overhang (pseudoblepharoptosis) to correct with frontal lift alone. Their excess may be removed just above the lashes or even in elderly persons’ mid-lid area. When they have a huge amount of skin redundancy, so much that maximal brow elevation fails to clear the visual obstruction simple skin or skin-muscle reduction helps tremendously (Fig. 33.32). It is one of the three indications for isolated upper lid plasty. (The other two are: young Asians whose brows are excessively elevated, and who will appear much more attractive with dropped brows. The third are those very unusual patients – usually Caucasians – who have little to no compensated brow ptosis and the resting brow is in an acceptable position, allowing direct excision of overhanging skin without the brow dropping further.) The problem created by some of these excisions, is that lines of dermal weakness that sometimes leave unanticipated lid creases, even from excisions just next to the lashes.

The lower lids and lateral canthus

By far the best procedure available for the lower lids is canthal restoration (canthopexy) which we preferably combine with a mid facial or malar lift.26,27 Frontal lifts or lateral juxta- brow-temple lifts are usually essential to prevent crowding in the lateral and brow temple areas. These combined procedures have become known as corono-canthopexy,28 or more recently by other names, Mag-5 being the most recent and hopefully the final name. They are indicated when extended canthopexy with two-layered canthopexies into bone and mid-cheek lifts are necessary.

Common among Asians is a type of midfacial retrusion that spares the malar eminences, which emphasizes the suborbital malar depressions. It was this frequent occurrence that inspired the senior author to begin fabricating tear trough implants in the early 1970s. This early experience with Asians led to cross-ethnic recognition of deformity and surgical correction. The extended canthopexy incision with its subperiosteal dissection makes a receptive bed requiring very little additional dissection for corrective implant placement and alleviation of the suborbital tear-trough deformities.

Inter-canthal tilt

There is a common misconception that most Asians have “slanted” eyes. Common eyelid configurations do however occasionally make apertures appear as slits. The inter-canthal axis is actually transverse in many Asians, and anti-Mongoloid tilts are not uncommon, especially in many Chinese populations. Typically the preferred upward tilt contour progressively drops as years pass. Restoration of these less attractive horizontal and downward tilting inter-canthal axes, both in young and mature Asians, makes a profound and positive difference in facial aesthetics (See Figures 33.5, 33.11, 33.24 and 33.33).

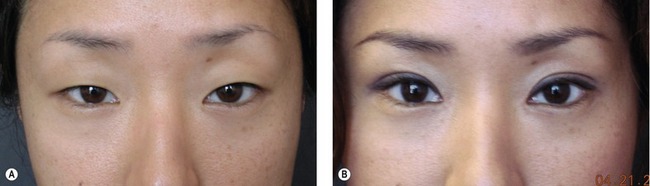

Don’t give up until you get it right

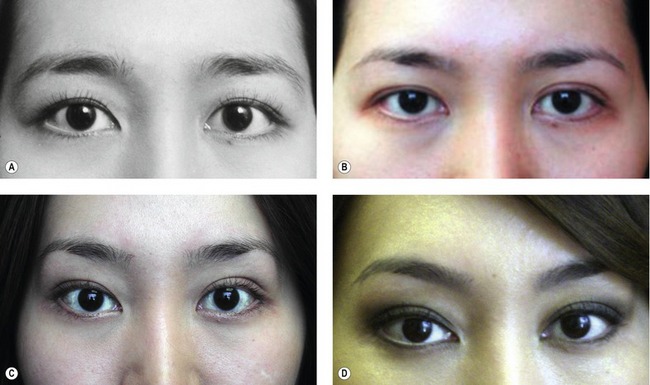

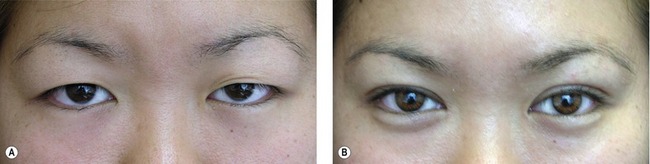

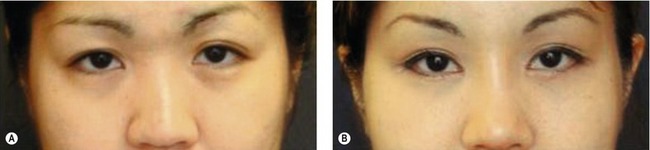

Minor (and sometimes major) adjustments are necessary to achieve the desired results. Sometimes multiple adjustments are necessary, often over several years. It may take a year or more to see the definitive outcomes of a surgical maneuver. The following patient is an excellent example of persistence and in the pursuit of eyelid excellence. The patient is a 22-year-old Asian American who wanted more attractive eyes. She sought out a board certified plastic surgeon with experience in Asian eyes. An invagination (open approach) type upper blepharoplasty was done, combined with a lower blepharoplasty. Figure 33.33A shows the patient prior to her surgery, done elsewhere.

Six months later she returned for our modified Uchida type medial epicanthoplasties together with modification of the lid fold on the right medial upper lid (Fig. 33.33C). Figure 33.33D is a late follow-up photograph taken four years following this last surgery. No other periorbital surgery took place.

Postoperative care

• Expect lid anchor and invagination procedures to have greater morbidity with a longer recovery than traditional blepharoplasty, but the lid folds are more precise and far longer lasting. Anticipate swelling of the pretarsal portion of the eyelid with variable degrees of blepharoptosis and a tugging sensation on opening the eye – especially on upward gaze – during the early postoperative period.

• The lids generally look acceptable at 2 weeks but commonly retain swelling which makes the pretarsal segments appear a bit larger than desirable for several months. The last tiny bit of swelling takes 2–3 years to disappear.

• Apply a light fluffy, well-padded, moderately compressive bandage to the periorbital area after surgery, removing it the following morning. This decreases ooze, swelling, edema, chemosis, and ecchymosis and touch. Keep the head elevated 30–45 degree for at least 48 hours to minimize swelling. Encourage the patient to continue this posture while sleeping for another 2 weeks – if possible. If the eyes are so swollen as to preclude vision, replace the bandage for another day and re-emphasize elevated sleep posture. This speeds the disappearance of swelling.

• After bandage removal, apply ice water compression continuously up to 36 hours postoperatively to maximally reduce swelling. Use no cold packs after 36 hours.

• Abstain from vigorous physical activity (including intimacy) for 2 weeks to avoid a pounding pulse and a rise in blood pressure which could result in bleeding into fresh wounds.

• Pain is rare after this type of surgery and is easily handled with acetaminophen.

• Avoid rubbing the eyes after surgery, which could loosen or break loose sutures and disrupt the wound. If itching is a problem it responds best to ice water soaks.

• Apply Lacrilube ointment before sleep and artificial tears several times a day for the two to eight weeks during which time the injured lids may not close with normal force.

• Remove all sutures (except the three that are key to the epicanthoplasty) on the fourth postoperative day.

• Take out the rest on the sixth or seventh postoperative day.

Complications

Brows

• Profound drop of the brows and accentuation of corrugator frown. This occurs commonly after upper lid blepharoplasty when compensated brow ptosis is not recognized and incorporated into the treatment plan, either simultaneously, or planned for a later date. Often people have to actually experience the brow drop to embrace the advised frontal lift.

• Brow asymmetry. Ninety percent of East Asians have significantly asymmetrical brows, with eighty percent lower on the right and ten percent lower the left. In the other ten percent, the brows are essentially equal. Unless the asymmetries are recognized and appropriately addressed, they will result in inequality of the double lid folds post-blepharoplasty.

Upper lids

• Extruding sutures. Anchoring sutures, even though absorbable, often extrude – because of their closeness to the surface. When a whisker of a suture is seen extruding through the skin, remove it promptly to avoid suture abscess and the possibility of an extended infection, treat with betadine solution or antibiotic ointment.

• Failure to create a well-defined, enduring crease. We have seen many attempts at fold creation by simply excising skin and muscle. Some continue to use Blair Rogers recommended cauterization-causing-scar technique,29 which cannot be expected to leave a well-defined and prominent crease. Others try to create a fold by simply removing skin and muscle where they would like to see a fold. Others secure the lid dermis to the filmy extension of the aponeurosis, rather than to the aponeurosis itself. If the aponeurosis seems too short to attach to the edge of the pretarsal dermis, slice the free margin of the aponeurosis into diagonal fingers, and rotate them caudally before attaching them to the dermis – or to dermis and tarsus (Fig. 33.34). Although three sutures suffice to make a crease, at least five are usually necessary for a complete and graceful one that echoes the full length of the upper lid margin. Most commonly, the failure is in the lateral lid where an extra suture or two will prevent the need for re-operation.

• Asymmetry competes with crease failure for the most common postoperative problem after Asian blepharoplasty. These asymmetries most frequently display themselves in different vertical heights of the pretarsal lid segment. Causes of this deformity are: (1) failure to recognize brow asymmetry and understand its effect on pretarsal skin height; (2) failure in accurate measuring and marking for lid incision and excision; (3) failure to recognize, or recognize and compensate for, (or treat) asymmetrical eyelid ptosis or retraction. (Asymmetrical retraction is commonly the result of an asymmetrically prominent globe and/or too aggressive an operation).

• Another asymmetry is lash eversion where one side has been attached higher than the other, either to the tarsus or aponeurosis. Attaching the dermis of the pretarsal skin flap to tarsus, as well as aponeurosis, checks against lash eversion.

• A third source of asymmetry is one fold diving beneath the epicanthus, and the other terminating just above it. This is best corrected by advancing and excising a triangle (or an additional triangle) as in our modified Uchida medial epicanthoplasty (Fig. 33.2).

• Hematoma. This can range from a minimal ecchymosis and subconjunctival hemorrhage to a small ooze into Müller’s muscle. Hematoma can cause problems ranging from temporary ptosis, to large retrobulbar hematoma.

• Lid ptosis. Varying degrees of blepharoptosis are common in the first few days postoperatively, usually subsiding without treatment. If we violate the supratarsal vascular arcade (Fig. 33.35) a hematoma in Müller’s muscle is likely. This causes lid ptosis lasting for 2 weeks to 2 months, before subsiding.

• The most common cause of persisting ptosis after surgery is undiagnosed preoperative ptosis, which is often exacerbated early postoperatively by stiffness and the increased weight of lid edema. (There is no substitute for a thorough preoperative examination!).

• Failure to document such a condition preoperatively and, at least point it out to the patient, inevitably results in blame assigned to the surgeon (due to increased scrutiny of one’s appearance after surgery). Another common cause of ptosis is iatrogenic injury to the levator aponeurosis, commonly caused by carelessly lifting the tissue while excising a strip of orbicularis muscle, inadvertently injuring the aponeurosis.

• Accidental shortening of the levator aponeurosis which is left unattached (to avoid retraction) doesn’t cause ptosis right away but will do so eventually. When the aponeurosis is too short it must be lengthened by diagonal fingers or by use of a temporalis fascia graft.

• Eyelid retraction. This results from fixation of pretarsal skin to a shortened levator aponeurosis, or to prominence of one or both eye globes. In both of these situations diagonal fingers can prove corrective. Resort to fascial graft, only if necessary (see Fig. 33.34).

• Excessively high or low creases. “Too high” usually means bad judgment, sloppy marking and/or faulty aesthetics. “Too low” probably means lack of understanding how gradual forehead and scalp relaxation with its accompanying brow descent can eliminate the very small fold visibility within a few years, or even less.

• Multiple creases. These generally arise from failure to eliminate old folds which were present preoperatively. This possibility is usually eliminated by opening the septo-aponeurotic sling across the lid. Extra lid creases are encouraged by suture, and half-open suture techniques, that are incapable of reaching up and disconnecting pre-existing connections. A very common cause of an extra crease in double eyelid surgery is an old scar remaining cephalad to the newly made fold. Even if all connections are released from the old scar, dermal weakness at the site of the incision will consistently result in an extra unwanted crease. Poor hemostasis and retained blood in the upper lid can create deep scarring, creating additional skin in-folding.

Lower lids

• Almost all complications in the lower lid result from lid laxity and atonicity which went uncorrected at the time of surgery. A good multiple layered canthopexy, preferably into the bone, and preferably with a mid-cheek lift, alleviates such repetitive iatrogenic deformity.

• Entropion. The most common cause is pre-existence. A second cause is making the canthopexy attachment too high up or too close to the margin of the lower lid.

• Loss of upward tilt of the intercanthal axis, even an anti-mongoloid tilt, is a common complication of Asian lower lid surgery. Excessive skin removal, resurfacing and failure to secure and restore tone with canthopexy are all causes.

• Lower lid depression. This is commonly seen in patients with thin lid fold or with deep-set eyes. Excessive fat removal is the cause of this complication.

Conclusion

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Have the patient close the eyes with a totally relaxed forehead to discover the true resting level of the brow. This is precisely how low the brow will descend after invagination blepharoplasty because of compensated brow ptosis.

• Use frontal lifts frequently in conjunction with, and sometimes instead of, lid invagination surgery.

• Use a lot of modified Uchida medial epicanthoplasties. It will bless your outcomes.

• Meticulously place, and meticulously remove medial epicanthoplasty sutures. Use 6-0 sutures with tapered needle.

• Use a contoured wire paper clip to demonstrate a lid fold to a prospective patient. Combine it with manual brow elevation to explain the benefit of combined frontal lifts.

Pitfalls

• Anchoring the lid fold to the deep tissue too close nasally will always cause the fold to dive beneath the medial epicanthal folds.

• Anchoring the skin to the aponeurosis too far laterally will cause the lateral lid fold to turn down at outside corner of the eye.

• Sutures left beyond 4 days on the eyelid will create suture tunnels. Rapid self absorbing sutures, although convenient and work saving, create wound deformity and lots of tunnels.

• Failure to notice an asymmetry ptosis and lid retraction preoperatively. Making symmetrical size folds will result in asymmetry postoperatively. Height of the pretarsal segment and amount of skin excision must vary with the position of asymmetrical brows.

• Lifting the orbicularis during muscle excision often injures the aponeurosis, making it too short to use in the operation.

Summary of steps

1. Flip the lid over and measure the vertical height of the tarsus.

3. Skin excision occurs separately from the removal of orbicularis muscle.

4. A sliver of orbicularis muscle juxtaposed to the caudal margin of skin excision is carefully removed.

5. Open the orbital septum across the lid.

6. Modification of the fat is performed.

7. Transect the pretarsal extension of the aponeurosis.

8. Removal of the filmy pretarsal connective tissue, including that which extends to the top of the tarsus, facilitates better fixation. Reduce the flap bulk.

9. Anchor the skin margin attaching the dermis of the pretarsal skin flap to the cephalad or anterior superior aspect of the tarsus, and to the free edge of the aponeurosis.

10. Use a running skin closure, including a small purchase of aponeurosis with each skin suture.

1. Flowers RS. The art of eyelid and orbital aesthetics: multi-ethnic considerations. Clin Plast Surg. 1987;14:703.

2. Flowers RS. Blepharoplasty and brow lifting. In: Roenigk RK, Roenigk HK, Jr. Dermatologic Surgery, Principles and Practice. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1989:1219–1221.

3. Mikamo K. A technique in the double-eyelid operation. J Chugaiijishinpo. 1896;17:1197.

4. Uchida K. The Uchida method for the double-eyelid operation in 1523 cases. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1926;30:593.

5. Maruo M. Plastic reconstruction of a “double eyelid”. Jpn J Clin Ophthalmol. 1929;24:393.

6. Millard R, Jr. Oriental peregrinations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1955;16:331.

7. Soyoc BT. Plastic reconstruction of the superior palpebral fold in slit eyes. Am J Ophthal. 1954;38:556.

8. Fernandez LR. Double eyelid operation on the Oriental in Hawaii. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1960;25:257.

9. Flowers RS. Anchor blepharoplasty. Presented at the Pan Pacific Surgical Association Congress in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 1972, and presented to the Annual meeting of the American Association of Plastic Surgeons, New Orleans, 1974.

10. Fernandez LR. The East Asian eyelid – open technique. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:247.

11. Uchida J. Cosmetic surgery of the eye. In: Handbook of Plastic Surgery. Tokyo: Nankado; 1969:175.

12. Flowers RS. Surgical treatment of the epicanthal fold. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;73:571.

13. Mustarde J. Repair and Reconstruction in the Orbital Region. Edinburgh: E&S Livingstone; 1980.

14. Flowers RS. Asian blepharoplasty and Asian rhinoplasty. Keynote lectures for the First Oriental Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery in Tokyo, Japan, 1988.

15. Flowers RS. What I have learned in 40 years of Oriental blepharoplasty. Presented at Pan-Pacific Surgical Association 28th Congress, Hawaii, January 2008.

16. Flowers RS. Frontal lifts as the key to periorbital aesthetics. Invited lecture to the Asian sectional meeting of the International Confederation of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons, Tokyo, 1982.

17. Flowers RS, Habbal MB, ed., Cosmetic blepharoplasty: state of art. Advances in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Mosby Yearbook, St. Louis (MO), 1992;Vol. 8:34–35.

18. Flower RS. Canthopexy as a routine blepharoplasty component. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:351.

19. Flowers RS. Advanced blepharoplasty principles of precision. In: Gonzales-Ulloa M, Meyer R, Smith JW, et al, eds. Aesthetic plastic surgery, Vol. 2. Padova: Piccin Press; 1987:119.

20. Flowers RS, Duval C. Blepharoplasty and Periorbital Aesthetic Surgery. In: Aston SJ, Beasley RW, Thorne CHM. Grabb and Smith’s Plastic Surgery. 5th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997:612.

21. Flowers RS. Asian blepharoplasty. Aesth Surg J. 2002;22:561.

22. Flowers RS, Nassif JM, Aesthetic periorbital surgery, 2nd edn. Mathes SJ, ed., Plastic surgery, Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2006;Vol. 2:108–110.

23. Flowers RS. Frontal lifts for young Asians. Postgraduate courses at ASPRS, ASAPS, and ISAPS,1984–2001.

24. Flowers RS. Optimal procedure in secondary blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:229.

25. Flowers RS. Upper blepharoplasty by eyelid invagination:anchor blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:202.

26. Flowers RS, Duval C. Blepharoplasty and Periorbital Aesthetic Surgery. In: Aston SJ, Beasley RW, Thorne CHM. Grabb and Smith’s Plastic Surgery. 5th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997:627.

27. Flowers RS. Blepharoplasty in the male. In: Courtiss E, ed. Male Aesthetic Surgery. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1981:231.

28. Flowers RS. Ceydeli. Mag-5: A magnificent approach to upper and midfacial “magic”. Clin Plast Surg. 2008;35:489–515.

29. Rogers BO. An Electrocauterization Technique for Cosmetic Blepharoplasty. In: Gonzales-Ulloa M, Meyer R, Smith JW, et al, eds. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, Vol. 2. Padova: Piccin Press; 1987:143.

mm more to account for the caudal end “bend” in the overhanging eyelid. This tells me the amount of skin to remove. Assessing it at two or more points assures precise removal all across the lid.

mm more to account for the caudal end “bend” in the overhanging eyelid. This tells me the amount of skin to remove. Assessing it at two or more points assures precise removal all across the lid. and 4 mm, rarely greater than 4 mm. For a 4 mm height I incise the skin 8–9 mm above the lash line (with the skin under stretch). For

and 4 mm, rarely greater than 4 mm. For a 4 mm height I incise the skin 8–9 mm above the lash line (with the skin under stretch). For  –

– mm, the incision is 8 mm above the lash line and for

mm, the incision is 8 mm above the lash line and for  –2 mm, 7 mm above the lash line. The latter measurements leave little room for subsequent brow drop.

–2 mm, 7 mm above the lash line. The latter measurements leave little room for subsequent brow drop.