CHAPTER 30 Blepharoplasty

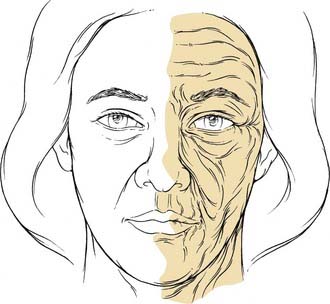

The aging process affects the skin and underlying tissues by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic aging refers to the effects of time on the skin. Over the course of one’s lifetime, the epidermis and subcutaneous fat layers thin and there is effacement of the dermal-epidermal junction. There are fewer Langerhans cells and melanocytes, and the morphology of the keratinocytes changes. There is a progressive loss of organization of elastic fibers and collagen (elastosis), and a weakening of underlying muscles. Extrinsic factors such as gravity, smoking, and sun exposure may result in keratinocytic dysplasia and accumulation of solar elastosis. Taken together, the intrinsic and extrinsic aging processes create pigmentary changes, rhytids, and texture irregularities of the skin (Fig. 30-1).1,2

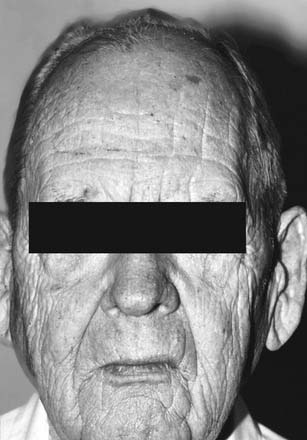

On a macroscopic level, aging results in brow ptosis, lateral brow hooding, crow’s feet, fine and deep rhytids, and loss of elasticity. Even though the effects of aging are normal, ubiquitous, and acceptable to many individuals, others find such changes to be an area of concern. In the periorbital region, the effects of aging may cause an individual to unintentionally convey external expressions of boredom, fatigue, and sadness, even though these are not the emotion being felt (Fig. 30-2). Because the eyes convey emotions, aging of the upper third of the face is almost always more visible and of greater impact than aging of the lower face and neck. To fully address the periorbital region surgically, it is first essential to understand its anatomy and aesthetic ideals.3

Anatomy

Orbital Anatomy

The lateral orbital wall is formed by the greater wing of the sphenoid and zygoma and is 47 mm long. The lateral orbital tubercle (Whitnall’s tubercle) is 10 mm below the zygomaticofrontal suture and 4 mm behind the anterior lateral orbital rim. The lateral canthal tendon, Whitnall’s ligament, and Lockwood’s ligament attach here. The medial orbital walls are 45 mm long. The medial wall is composed of the frontal process of the maxilla, the lacrimal bone, the lamina papyracea (ethmoid bone), and the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone. The anterior lacrimal crest forms the attachment for the medial canthal tendon. The lacrimal fossa and sac lie between the anterior and posterior lacrimal crests. The anterior and posterior ethmoid foramina transmit the anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries and demarcate the level of the cribriform plate and floor of the cranial fossa. The average distance from the anterior lacrimal crest to the anterior ethmoid foramen is 24 mm, to the posterior ethmoid foramen is 36 mm, and to the optic foramen is 42 mm.4

The orbital floor is formed by the zygomatic bone, the orbital plate of the maxilla, and the orbital process of the palatine bone. The orbital floor ends at the inferior orbital fissure posteriorly, which transmits the sphenopalatine ganglion, and the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve. The infraorbital neurovascular bundle travels through the infraorbital groove, canal, and foramen. The infraorbital foramen lies 8 mm inferior to the inferior orbital rim.4

The optic foramen, within the lesser wing of the sphenoid, transmits the optic nerve, ophthalmic artery, and sympathetic fibers to the orbit. The superior orbital fissure is bounded by the greater and lesser wings of the sphenoid. The annulus of Zinn is a fibrous ring surrounding the optic foramen and superior orbital fissure. The superior orbital fissure transmits cranial nerve IV, ophthalmic and mandibular divisions of cranial nerve V, cranial nerve VI, the nasociliary nerve, the superior and inferior ophthalmic veins, the lacrimal nerve, and the frontal nerve.4

Eyebrow Anatomy

Sensory Innervation

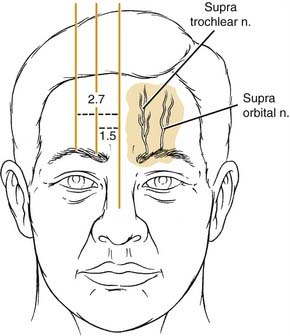

Sensation of the brow and anterior scalp region is provided by the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. The ophthalmic division divides into the lacrimal nerve, which provides sensation to the skin and conjunctiva of the upper eyelid, and the frontal nerve, which further divides into the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves. The supratrochlear innervates the conjunctiva, upper eyelids, and inferomedial aspect of the forehead, whereas the supraorbital nerve innervates the upper lid skin, forehead, and anterior scalp. The supratrochlear nerve lies 1.5 to 1.7 cm from the midline, and the supraorbital nerve lies 1 cm lateral to the supratrochlear nerve (Fig. 30-3).5

Motor Innervation

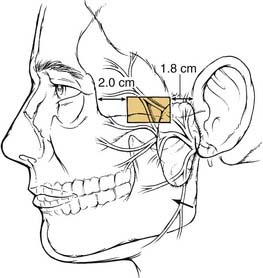

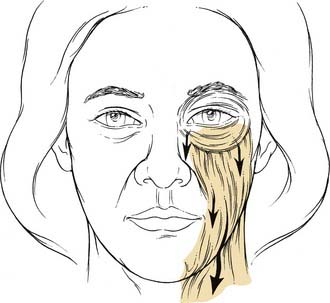

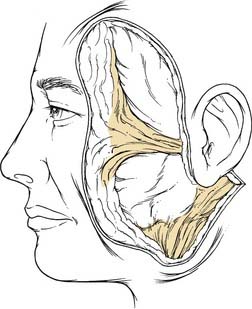

The temporal, or frontal, division of the facial nerve supplies the muscles of the forehead and the orbicularis oculi muscle. This division of the facial nerve courses from the parotid gland, anterior to the superficial temporal artery, toward its final destination, where it pierces the undersurface of the frontalis muscle 1.5 cm above the lateral canthus. The frontal branch of the facial nerve lies deep to the superficial musculoaponeurotic system fascia (SMAS) and its continuation in the temporal region, the temporoparietal fascia (Fig. 30-4). The course of the nerve may be approximated by a line drawn from a point 0.5 cm anterior to the tragus to a point 1.5 cm lateral to the lateral brow. The danger zone for the temporal branch of the facial nerve has been further described and is shown in Fig. 30-5. The nerve enters the orbicularis oculi muscle and frontalis muscle along the deep surface of the muscles. As the nerve crosses over the zygomatic arch, it lies between the periosteum of the zygoma and the SMAS. Dissection in the region of the zygomatic arch requires caution to avoid injury to the nerve and should be carried out either subcutaneously or subperiosteally.4,5

Figure 30-4. Temporal branch of facial nerve deep to the superficial musculoaponeurotic system fascia and temporoparietal fascia.

(From Weinberger MS, Becker DG, Toriumi DM. Rhytidectomy. In: Cummings C, Fredrickson J, Harker L, Krause C, Richardson M, Schuller D, eds. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998:650.)

Fascial Layers of the Forehead and Temporal Region

The scalp consists of five layers: the skin, subcutaneous tissue, galea aponeurosis, loose areolar tissue, and periosteum. The galea is a tendinous, inelastic sheet of tissue that connects the frontalis muscle of the forehead with the occipitalis muscle. The frontalis muscle originates from the galea and inserts into the forehead skin. At the superior orbital rim, the galea becomes tightly adherent to the periosteum. Laterally, the galea continues as the temporoparietal fascia, which lies in the immediate subcutaneous plane in the temporal region. The temporoparietal fascia is continuous with the SMAS layer of the face and the platysmal layer of the neck (Fig. 30-6). Deep to the temporoparietal fascia lies the deep temporal fascia, which envelops the temporalis muscle. The temporal fascia is contiguous with the calvarial periosteum at the temporal line of the skull, the conjoint tendon. The temporal fat pad, just superior to the zygomatic arch, is ensheathed by the temporal fascia inferior to the level of the supraorbital ridge. At that point, the temporal fascia splits to become the intermediate temporal fascia and the deep temporal fascia, with the fat pad between them. The intermediate fascia layer attaches to the superior aspect of the zygoma laterally, whereas the deep layer attaches medially.4,5

Figure 30-6. The superficial musculoaponeurotic system and the temporoparietal fascia is one continuous layer.

(From Weinberger MS, Becker DG, Toriumi DM. Rhytidectomy. In: Cummings C, Fredrickson J, Harker L, Krause C, Richardson M, Schuller D, eds. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998:649.)

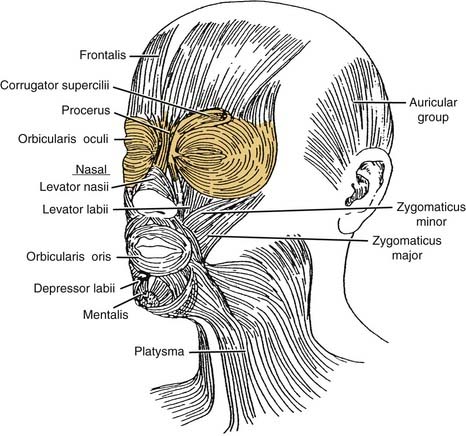

Musculature

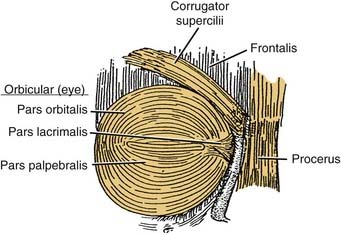

There are four muscles in the eyebrow: frontalis, procerus, corrugator supercilii, and orbicularis oculi (Fig. 30-7). The frontalis is a paired subcutaneous muscle that inserts into the skin of the eyebrow. It is the continuation of the galea aponeurotica from the coronal suture downward, and inserts in the dermis at the level of the supraorbital ridge. Laterally, the frontalis terminates at the conjoined tendon. The frontalis muscle has no bony insertions, and its only action is brow elevation. Horizontal forehead rhytids correspond to the long-term effects of frontalis activation. Inferonasally, the frontalis muscle extends to form the procerus muscle. The procerus originates on the caudal aspect of the nasal bones and cephalic margins of the upper lateral cartilages, and inserts onto the medial belly of the frontalis muscle and the dermis between the eyebrows. The action of the procerus muscle produces inferior brow displacement and is responsible for horizontal glabellar wrinkles (Fig. 30-8).

Figure 30-7. Eyebrow muscles include the frontalis procerus, corrugator supercilii, and orbicularis oculi.

(From Graney DO, Baker SR. Anatomy. In: Cummings C, Fredrickson J, Harker L, Krause C, Richardson M, Schuller D, eds. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998:404.)

The corrugator muscle originates from the nasal process of the frontal bone, near the superomedial orbital rim, and inserts into the dermis at the middle third of the eyebrow after blending with the frontalis and orbicularis muscles. Its action produces inferior and medial forehead and brow movement, and results in vertical glabellar wrinkle.4,5

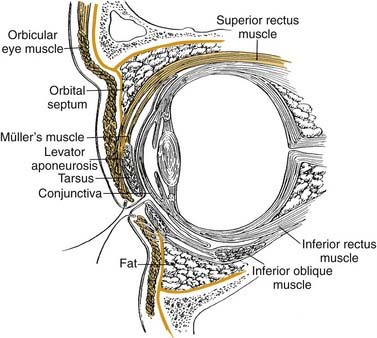

Eyelid Anatomy

The eyelids are the protective covering over the eyes. They consist of an anterior and posterior lamella. At the level of the tarsal plates, the upper and lower eyelids consist of the same basic components: The anterior lamella consists of skin and orbicularis oculi muscle; the posterior lamella consists of tarsus and conjunctiva. The two lamellae are separated by finely interdigitating eyelid retractors. The anterior and posterior lamellae have separate blood supplies that are important to recognize when approaching eyelid reconstruction (Fig. 30-9).4

Figure 30-9. The cross section of the orbit and eyelid.

(From Colton JJ, Beekhuis GJ. Blepharoplasty. In: Cummings C, Fredrickson J, Harker L, Krause C, Richardson M, Schuller D, eds. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998:680.)

Surface Anatomy of the Eyelids

The normal horizontal palpebral fissure is 28 to 30 mm and the normal vertical palpebral fissure is 9 to 10 mm. The intercanthal distance, the distance between the medial canthi of the two eyes, is approximately 25 to 30 mm. The upper eyelid margin normally rests at a point midway between the superior corneal limbus and the pupil, whereas the lower eyelid margin typically abuts the inferior corneal limbus. The apex of the upper eyelid is located midway between the medial pupillary margin and the medial corneal limbus. The nadir of the lower eyelid is at the lateral corneal limbus.6

The upper lid crease is the line formed by the insertion of the levator aponeurosis and orbital septum into the orbicularis oculi muscle and skin. In women, the lid crease is 10 to 12 mm above the lid margin, whereas in men it is 7 to 8 mm above the lid margin. The lateral canthal angle is more acute and 2 mm higher than the rounded and lower medial canthal angle (Fig. 30-10).4,6

Figure 30-10. The lid crease is 10 to 12 mm above the lid margin in women and 7 to 8 mm above the lid margin in men.

(From Colton JJ, Beekhuis GJ. Blepharoplasty. In: Cummings C, Fredrickson J, Harker L, Krause C, Richardson M, Schuller D, eds. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998:678.)

A number of anatomic differences exist between the Asian and Occidental eyelids. In the Asian eyelid, the orbital septum and levator aponeurosis attach to the skin further inferiorly, anterior to the tarsus. As a result, orbital fat prolapses anteriorly, thereby preventing the formation of a prominent upper eyelid crease and creating a fullness of the upper eyelid.4,5

The Anterior Lamella

The skin of the eyelids is the thinnest skin of the body with almost no reticular dermis, and it is highly vascular. These factors allow the eyelid skin to heal rapidly and with minimal scar. As it approaches the orbital rim and the hair-bearing areas of the periorbital region, the skin of the eyelids thickens rapidly. The changes in skin thickness are important to consider when planning incisions in periorbital surgery (see Fig. 30-9).4–6

The orbicularis oculi muscle is a subcutaneous muscle that serves as the sphincter of the eyelid. It is innervated by the temporal and zygomatic branches of the facial nerve. In addition to its function in eye closure, the orbicularis oculi muscle is essential for the proper functioning of the lacrimal pump apparatus, which propels tears into the puncta, canaliculi, and lacrimal sac. Failure of the pump mechanism, as may result with facial nerve paralysis, may result in epiphora.4–6

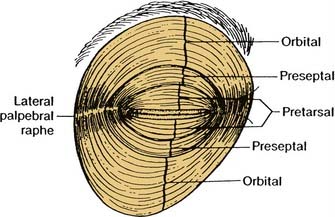

The orbicularis oculi muscle is divided into three segments: the pretarsal, preseptal, and orbital segments (Fig. 30-11). Even though they all act to close the eye, each segment plays a unique role. Blinking is an involuntary action that depends on contraction of the pretarsal orbicularis. Winking is a voluntary action dependent upon the orbital orbicularis. The preseptal fibers contribute to both the involuntary and voluntary functions of the eyelids.4–6

Figure 30-11. The sphincter mechanism of the eyelids depends on the three divisions of the orbicularis oculi muscle.

(From Colton JJ, Beekhuis GJ. Blepharoplasty. In: Cummings C, Fredrickson J, Harker L, Krause C, Richardson M, Schuller D, eds. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998:679.)

The origin of the pretarsal orbicularis arises from two heads, one of which inserts into the posterior lacrimal crest, and the other inserts into the anterior lacrimal crest and into the anterior limb of the medial canthal tendon. The preseptal orbicularis also has two heads at its origin: the deep portion attaches to the lacrimal sac, and the superficial segment attaches to the anterior limb of the medial canthal tendon. The orbital orbicularis originates at the anterior limb of the medial canthal ligament and interdigitates with the frontalis, corrugator, and procerus muscles. Laterally, the three orbicularis segments fuse to form the inferior and superior crura of the lateral canthal tendon, which insert into Whitnall’s tubercle. The lateral attachments of the lateral canthal tendon to Whitnall’s tubercle are responsible for eyelid and globe apposition.4–6

The Orbital Septum

The orbital septum, which lies just deep to the orbicularis oculi muscle, forms the anterior border of the orbit and confines the orbital fat (see Fig. 30-9). It is a fibrous sheath formed at the orbital rims at the arcus marginalis and is an extension of the orbital periosteum. In white upper lids, the septum fuses with the levator aponeurosis approximately 3 mm above the superior tarsal border. In Asian upper lids, the septum fuses with the levator aponeurosis further inferiorly, below the superior tarsal border, thereby allowing orbital fat to lie anterior to the tarsal plate, preventing the attachment of the levator to the skin, and preventing the formation of an upper eyelid crease. In the lower lids, the septum fuses with the underlying orbital retractor (capsulopalpebral fascia), 5 mm below the inferior tarsal border. The orbital septum acts as a barrier to the spread of infection and neoplasms between the preseptal space and the orbital space.4

The Orbital Fat Pads

All of the eyelid fat pads lie deep to the orbital septum. The upper eyelid contains two fat pads medially and centrally, and the lacrimal gland laterally (Fig. 30-12). The lacrimal gland should be avoided during eyelid surgery to prevent postoperative dryness; it can be identified by its pink rather than yellow color and its firm rather than soft texture.4,6

The lower eyelid contains three fat pads: medial, central, and lateral. The medial and central fat pads are separated by the inferior oblique muscle, which should be identified during lower eyelid surgery to help prevent its disruption. Disruption of this muscle may result in postoperative diplopia (see Fig. 30-12).4,6

Upper Eyelid Retractors

Deep to the fat pads are the eyelid retractors. In the upper lid, the levator palpebrae superioris (the levator muscle) is the major retractor, and it originates from the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone at the orbital apex (see Fig. 30-9). The levator is innervated by the oculomotor nerve (cranial nerve III). The horizontal posterior segment of the levator consists of muscle fibers, which extend anteriorly along the orbital roof for 36 mm until it reaches Whitnall’s ligament. At Whitnall’s ligament, the levator changes its course by approximately 90 degrees and becomes an aponeurosis that travels vertically for a length of 14 to 20 mm until its insertion into the upper third of the tarsal plate. Some fibers of the levator aponeurosis fuse with the orbital septum approximately 2 to 5 mm above the superior tarsal border, and then together insert into the skin to create the upper eyelid crease. In addition to its inferior attachments to the septum, tarsal plate, and skin, the levator aponeurosis attaches medially to the medial canthal tendon, and laterally to the lateral canthal tendon.4

Müller’s muscle, or the superior tarsal muscle, arises from the undersurface of the levator aponeurosis just below Whitnall’s ligament, and courses inferiorly 10 to 12 mm to attach to the superior tarsal plate (see Fig. 30-9). Müller’s muscle is innervated by sympathetic nerve fibers, and its action produces 2 to 3 mm of eyelid retraction. Müller’s muscle is adherent to the levator aponeurosis anteriorly and is loosely adherent to the conjunctiva on its posterior surface.4

Lower Eyelid Retractors

The capsulopalpebral fascia and inferior tarsal muscle comprise the lower eyelid retractors. The capsulopalpebral fascia originates from the fascia of the inferior rectus muscle and inserts on the inferior tarsal border. This fascia does not move independently, but rather mimics the movement of the inferior rectus muscle from which it originates. The inferior tarsal muscle arises from the undersurface of the capsulopalpebral fascia and the two are tightly adherent to each other and to the lower lid conjunctiva. The inferior tarsal muscle is sympathetically innervated.4,6

The Tarsus

The tarsal plates are dense fibrous connective tissue that form the skeleton of the eyelids (see Fig. 30-9). Each plate is 25 to 30 mm in horizontal dimension. The upper eyelid tarsal plate is 10 to 12 mm in vertical height while the lower eyelid tarsal plate is 3 to 5 mm in vertical height.4

The Conjunctiva

The conjunctiva is the innermost surface of the eyelid, which is in contact with the globe (see Fig. 30-9). It is composed of nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium with goblet cells that produce the mucous layer of the tear film. The bulbar conjunctiva is the portion of the conjunctiva that lines the globe, whereas the palpebral conjunctiva lines the eyelid. These two segments meet at the conjunctival fornix, at the base of the upper and lower eyelids. Dispersed throughout the conjunctiva are numerous additional glands that produce the aqueous layer of the tear film. The lacrimal gland secretes additional lacrimation in response to stimuli such as ocular irritant and emotional triggers.4

Midface Anatomy

With aging, the malar prominences descend inferomedially to deepen the nasolabial crease and expose the inferior and lateral orbital rims to a greater degree. In addition to the underlying bony malar eminence, the malar prominence is formed by a variety of soft tissue components. The orbicularis oculi muscle extends beyond the eyelids to lie over the malar eminence. In youth, the orbicularis maintains a sling around the orbital rim, but with the loss of orbicularis tone associated with aging, descent of the malar soft tissue complex prevails (Fig. 30-13). Both the superficial and deep surfaces of the malar orbicularis oculi muscle are associated with a fat pad. Superficial to the orbicularis is the subcutaneous malar fat pad. Deep to the orbicularis lies the suborbicularis oculi fat, also known as the SOOF. The SOOF layer of fat is in close contact with the periosteum of the inferior orbital rim as well as with the insertions of the zygomaticus muscles. The zygomaticus major and minor muscles are innervated by the zygomatic and buccal branches of the facial nerve and enter the muscle on its deep surface.7

Aesthetic Considerations and Ideals in the Periorbital Area

In an attempt to rejuvenate the periorbital area in the most natural and aesthetically pleasing way, consideration must be given to all of the elements that constitute this region. If the ravages of aging have caused upper face and midface changes, the surgeon must recognize that correcting the ocular problems alone will not give the patient a harmonious cosmetic result. Rather, the upper face contribution to the aging periorbital area as well as the midface contribution to the aging periorbital area must be considered. Brow position, glabellar rhytids, dermatochalasia, eyelid ptosis, pseudoherniation of fat, lateral crow’s feet, inferior malar displacement, ptotic lacrimal gland, and eyelid laxity should all be taken into account when addressing the periorbital complex.8,9

Brow Position

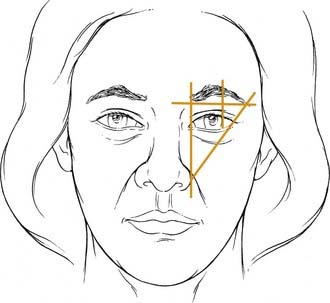

Management of brow malposition necessitates an understanding of the ideal brow position. Evaluation of the patient should include an examination in front of a mirror in both animation and repose. The patient’s eyes should be closed for 10 to 20 seconds to allow for full relaxation of the forehead musculature. Upon eye opening, the true position of the brow is noted with minimal contribution to the brow position from the forehead muscles. The ideal brow anatomy in the male differs from that in the female. The classic brow position in women describes the medial brow as having its medial origin at the level of a vertical line drawn to the nasal alar-facial junction. The lateral extent of the brow should reach a point on a line drawn from the nasal alar-facial junction through the lateral canthus of the eye. The medial and lateral ends should lie on the same horizontal plane (Fig. 30-14). The medial end should have a clubhead appearance and the lateral end should gradually taper to a point. The brow should arch superiorly, well above the supraorbital rim, with the highest point classically described as lying at the lateral limbus, and more recently described as lying at the lateral canthus. In men, there should be less of an arch to the brow position and more of a horizontal contour along the supraorbital ridge. The distance between the midpupillary line and the inferior brow border should be approximately 2.5 cm. The distance from the superior border of the brow to the anterior hairline should be 5 cm.5,10

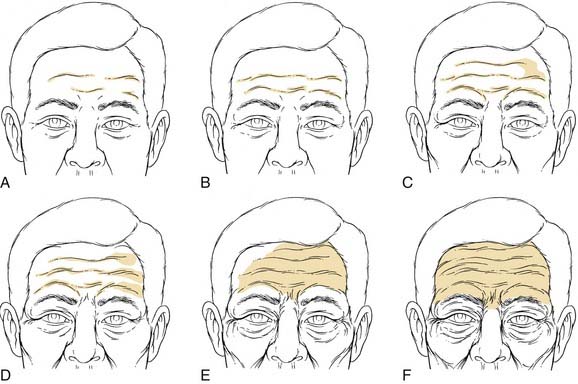

The upper one third of the face elongates with aging as a result of the hairline moving upward and the brow drifting downward (Fig. 30-15). In addition to brow ptosis, the aging brow may reveal dynamic wrinkles or even wrinkles at rest. These furrows in the glabella and forehead are caused by the repeated pull on the skin by the facial mimetic muscles. The distance between the two eyebrows should be the same as the distance between the alar-facial junctions on the two sides of the nose.

Figure 30-15. Elongation of the upper third of the face with associated wrinkles at rest and ptotic brows.

Brow ptosis not only gives the face a tired, crowded, angry, and unattractive appearance, it may also accentuate upper eyelid skin redundancy. As the brow descends below the supraorbital rim, it pushes additional skin over the upper eyelid, worsening the cosmetic appearance of the eyelids and aggravating the functional deficits in the peripheral visual fields. Upper eyelid blepharoplasty alone will not correct the patient’s problem and may even worsen the degree of brow ptosis by fixing the brow in an inferior position. Therefore attention to the repositioning of the brow is essential and should be done before blepharoplasty.11

Eyelid Aesthetics

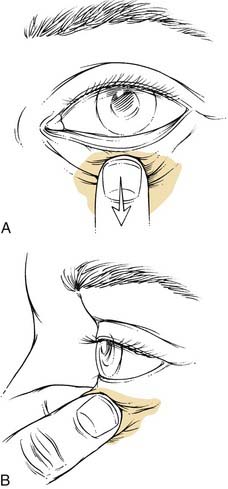

Several reproducible themes have been noted in the analysis of beautiful eyes and eyelids. The palpebral fissure should be almond shaped and symmetrical between the two sides. The highest point of the upper eyelid is at the medial limbus, and the lowest point of the lower eyelid is at the lateral limbus. Sharp canthal angles should exist, especially at the lateral canthus. The lateral canthus should lie 2 to 4 mm superior to the medial canthus. The horizontal dimension of the palpebral fissure is 25 to 30 mm, whereas its vertical dimension is approximately 10 mm. Vertical palpebral asymmetry may indicate the presence of true ptosis of the eyelid, which would necessitate ptosis repair. The upper eyelid orbicularis muscle should be smooth and flat, and the upper eyelid crease should be crisp. The upper lid crease should lie between 8 and 12 mm from the lid margin in the white patient. A more inferior position of the upper lid crease gives a heavy and tired appearance to the eye. Excessive lid folds, tissue prolapsing over the upper eyelid crease, should be minimal to avoid the aged and tired look (Fig. 30-16). The upper lid margin should cover 1 to 2 mm of the superior limbus, while the lower lid margin should lie at the inferior limbus or 1 mm below the inferior limbus. Note should be made of excessive skin, muscle, and orbital fat. The pinch test helps determine the degree of excess lid skin that is present. The snap test helps determine the degree of lower lid laxity and is useful in preoperative planning (Fig. 30-17). The lower eyelid is distracted from the globe, and an audible snap should be heard if the eyelid is not significantly lax. Additionally, a ptotic lacrimal gland must be recognized for potential correction at surgery. Excessive lateral skin hooding may require skin excision beyond the lateral orbital rim, and prolonged wound healing would be expected in this area of greater skin thickness—a point that must be relayed to the patient before surgical intervention.12,13

The lower eyelid should closely appose the globe without drooping of the lid away from the globe (ectropion) or in toward the globe (entropion). Excessive lower eyelid laxity should be recognized with the snap test, and when present, a lid shortening/tightening procedure should be performed in conjunction with blepharoplasty. Exophthalmos and enophthalmos should be recognized—neither is favorable—and each may represent an underlying disorder. Visual acuity should be evaluated, as should the presence of a Bell’s phenomenon. Absence of the Bell’s phenomenon places the patient at increased risk for the development of postoperative corneal abrasions if temporary or permanent lagophthalmos occurs after surgery. If the patient exhibits signs of a dry eye, the Schirmer test should be performed, and caution should be used in deciding on surgical intervention.13,14

Upper Eyelid Ptosis

Evaluation

Finally, patients should be questioned about dry eye symptoms and tear secretion should be evaluated, because dry eye may be exacerbated after ptosis surgery. Schirmer test paper is used to estimate tear secretion (Fig. 30-18). If the wet paper measures less than 5 mm after 5 minutes with the use of topical anesthetic, there is a possibility of further complications. A punctal plug inserted postoperatively allows for an increased reservoir of natural tears; however, the patient must be counseled that dry eye symptoms may worsen.

Midface Aesthetic Ideals

A prominent cheek bone and malar eminence conveys a youthful appearance. As time advances, the tone of the orbicularis oculi muscle is weakened and the sling that helped maintain the soft tissue fullness in the malar eminence can no longer support the underlying structures. The inferior and lateral orbital rims should be padded with malar fat and SOOF. Descent of the subcutaneous malar fat pads, as well as the suborbicularis oculi fat, results in a flattened malar eminence and prominent orbital rims, which are aesthetically unpleasant (see Fig. 30-13). In cases of ptotic midfacial structures and exposure of the orbital rim, the juxtaposition of prolapsed orbital fat and the fallen SOOF results in a double contour. Restoring the fallen SOOF to its more youthful position with a midface lift eliminates the double contour.7

Surgical Techniques

Blepharoplasty and Ptosis Repair

Upper Eyelid

Success in blepharoplasty requires that the surgeon understand the aesthetic relationships between the eyelids, eyebrows, forehead, orbit, and midface. These aesthetic ideals are discussed earlier in the chapter and may be reviewed. Once the individual patient’s good medical health, psychological motivations, and expectations regarding the surgery are understood to be reasonable, the surgery may proceed. Typically, blepharoplasty is performed as outpatient surgery under either local or general anesthesia.12

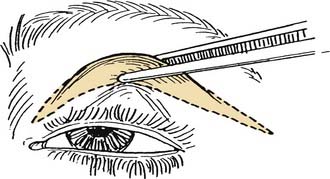

If performed in conjunction with a browlift, the blepharoplasty incision markings are placed after the browlift is complete and all incisions have been closed. Marking the eyelids is the single most important step in blepharoplasty, and as such, great care must be taken to ensure precision (Fig. 30-19). If there is no eyelid ptosis, the initial lid marking is made at the natural skin crease or 1 mm above the natural crease. Making the incision 1 mm above the natural crease allows for wound contracture to bring the ultimate lid scar into the proper position at the natural crease. Generally, the lid crease is at the same level bilaterally, but if not, the incisions may be designed to create lid symmetry with the use of a caliper. The medial end of the incision descends approximately 1 to 2 mm from the central vertical height and is carried to the punctum of the medial canthus but not beyond the punctum. Incisions medial to the punctum and beyond the nasal orbital depression may cause irreversible webbing. The lateral extent of the incision curves upward slightly, within a natural crease in the sulcus between the orbital rim and the eyelid. The lateral extent is determined by the degree and location of lateral hooding, and may even extend beyond the lateral orbital rim. The patient must be told preoperatively that the skin incision lateral to the lateral orbital rim will take longer to heal because the skin thickens beyond the lateral orbital rim. To determine the amount of redundant skin to excise, the pinch test is performed (Fig. 30-20). One blade of a Graefe forceps grasps the skin at the previously marked lid crease, and the other blade grasps the skin at a point superiorly, which just smooths out the skin of the eyelid until slight eversion of the lid occurs. This technique helps prevent postoperative lagophthalmos. Leaving approximately 20 mm of eyelid skin may also help prevent postoperative lagophthalmos. The superior extent of the eyelid skin can be identified by palpating the abrupt transition from the thin upper eyelid skin to the thicker eyebrow skin. The inferior extent of the brow cilia should be avoided as an endpoint because the patient may have epilated and therefore altered the apparent end of the inferior brow.6 Both the medial and lateral ends of the upper lid fusiform excision should form a 30-degree angle.12,14

Figure 30-20. The pinch test helps determine the amount of lid skin to be excised.

(From Colton JJ, Beekhuis GJ. Blepharoplasty. In: Cummings C, Fredrickson J, Harker L, Krause C, Richardson M, Schuller D, eds. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998:687.)

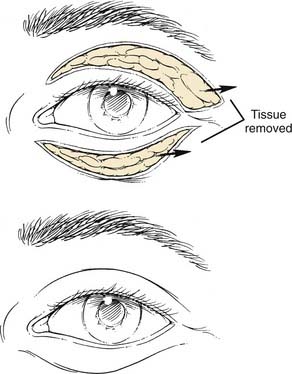

Once the markings are complete, local infiltrative anesthesia is injected in the immediate subcutaneous plane. If ptosis surgery is also being performed, care should be taken to ensure that the minimum amount of local anesthesia is used so as to not affect the underlying levator. Usually 1 to 2 mL of local anesthesia is all that is needed. After adequate time is given for the anesthetic to take effect, the skin incisions are made with a fresh blade of the surgeon’s choice, and the skin is taken as a single layer or as a two-layer skin-orbicularis unit (see Fig. 30-20). If skin only is excised, a determination is subsequently made regarding the amount of orbicularis oculi muscle to excise. Resection of a strip of orbicularis along the inferior length of the skin excision helps recreate a distinct upper eyelid skin crease. A variable amount of orbicularis oculi muscle should be resected, depending on the degree of muscle hypertrophy.

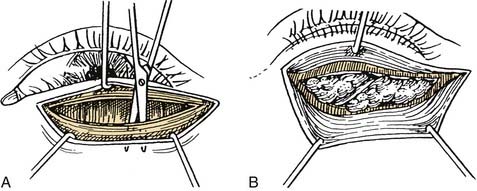

Resection of orbicularis exposes the orbital septum and allows visualization of the orbital fat through the septum. Two different techniques may be used to address the pseudoherniation of fat. Bovie cautery of the orbital septum contracts the septum and reduces the degree of fat pseudoherniation as has been described for lower lid blepharoplasty.15 Alternatively, opening the orbital septum and removing fat from the medial and central compartments may be achieved (Fig. 30-21). Clamping the fat that will be removed, followed by cauterization of the fat in the clamp, helps prevent postoperative hematomas. Anterior traction should not be placed on the clamp to prevent avulsion, bleeding, and excessive resection. Only fat that protrudes into the wound with gentle globe pressure should be clamped and excised to avoid overaggressive removal of orbital fat and a hollowed postoperative look. However, care should be used to help avoid the common error in upper eyelid blepharoplasty of failing to remove enough of the medial orbital fat. Laterally, the lacrimal gland may come into view and should be recognized to avoid its injury. The lacrimal gland is more pink, vascular, and firm than is the fat.

If only blepharoplasty is performed, after excellent hemostasis is achieved, wound closure proceeds with a single layer closure of the skin with a 6-0 fast-absorbing gut suture.12,14 However if ptosis surgery is also going to be performed, then the lower edge of the incision is grasped with a Castroviejo forceps (0.3 or 0.5) and the pretarsal orbicularis is dissected medially and laterally to expose the surface of the tarsal plate (see Fig. 30-21). Next, this strip of orbicularis can be removed to further debulk the lid fold and expose the underlying layers to help identify the levator aponeurosis. An important landmark for identifying the levator aponeurosis is the preaponeurotic fat pad. It lies posterior to the orbital septum and is anterior to the levator. A cotton tip applicator can be used for gentle dissection and may help prevent inadvertent damage to the underlying levator. Once identified, the orbital septum should be opened medially and laterally because leaving the orbital septum attached may result in postoperative lid lag or lagophthalmos. A Desmarres retractor can be used to retract the fat, exposing the underlying levator aponeurosis. To ensure that one has correctly identified the levator, the patient can be asked to look up while grasping the levator. If identified appropriately, a force is transmitted via the forceps. A double-armed 6-0 silk suture can be used as a cardinal suture by passing it in a horizontal mattress fashion through the tarsal plate approximately 5 mm from the lash line. This tarsal bite should be approximately half thickness, because a full-thickness bite may lead to postoperative keratopathy. The sutures are then passed through the cut edge of the aponeurosis and tied in a slip knot. The position of the lid may then be assessed and additional horizontal mattress sutures may be placed medially or laterally to adjust the lid contour. Initially, a slight overcorrection may be desired to allow for postoperative descent that may occur from the stimulation of Müller’s muscle by the local anesthesia. Once the desired height and contour are achieved, the sutures may be tied down and the skin closed as described previously.6,13,20

Lower Eyelid Blepharoplasty

Transconjunctival

The transconjunctival blepharoplasty has become increasingly popular over the past few years due to the hidden incision, the maintenance of the orbicularis support structure for the lower eyelid, and a reduced rate of postoperative ectropion. Proper patient selection is required for the successful use of this technique in blepharoplasty. Patients with pseudoherniation of fat and little need for skin excision are good candidates for this procedure. In addition, patients who heal with hypertrophic scars, and patients who will not accept an external incision are good candidates. The presence of a mild to moderate amount of excess skin in the lower eyelid does not preclude the transconjunctival approach, in that a pinch excision of skin and lid resurfacing techniques may be used to address the lower lid skin changes.13

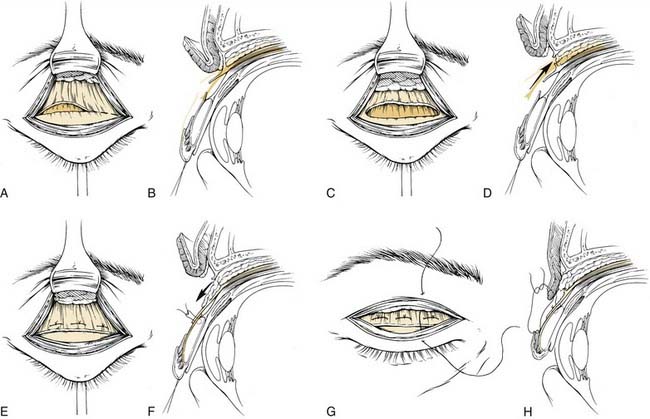

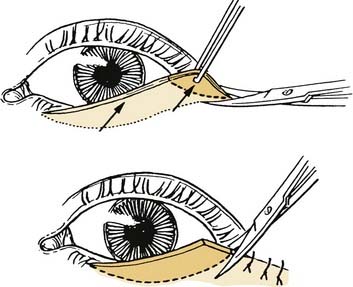

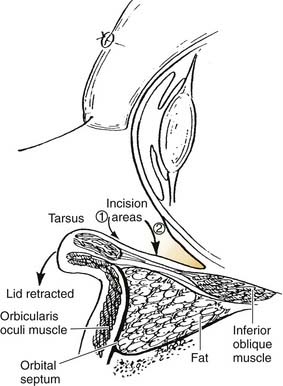

After local anesthetic is injected and adequate time is allowed for the vasoconstriction to take effect, the lower eyelid conjunctival surface is exposed. Either a preseptal or postseptal approach may be used, depending on the surgeon’s preference (Fig. 30-22). A 4-0 silk suture is placed through the eyelid margin for traction. The traction suture, together with a Desmarres retractor, helps evert the lower eyelid. The preseptal approach involves a transconjunctival incision made at the inferior margin of the tarsal plate. A plane is developed just deep to the orbicularis muscle in the avascular plane between the orbicularis muscle and orbital septum, down to the level of the orbital rim, without exposing the orbital rim. A 4-0 silk suture is then passed through the conjunctival edge to provide traction and corneal protection. The orbital septum is then in clear view and may be entered with the Bovie cautery.

Figure 30-22. Preseptal (1) and postseptal (2) transconjunctival approaches to blepharoplasty.

(From Colton JJ, Beekhuis GJ. Blepharoplasty. In: Cummings C, Fredrickson J, Harker L, Krause C, Richardson M, Schuller D, eds. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998:693.)

Alternatively, the postseptal approach may be used; this entails a single incision placed 4 mm below the inferior tarsal margin, directly through the conjunctiva and lower eyelid retractors, to expose orbital fat from the posterior aspect. The orbital septum is maintained completely intact in this technique. Traction sutures of 4-0 silk or nylon are placed on either side of the transconjunctival incision to allow for blunt and sharp dissection throughout the lower eyelid retractors to the orbital fat. Identification of the inferior oblique muscle, which separates the medial from the middle fat pads, should be performed in both the preseptal and postseptal methods to avoid injury to this structure. The fat is excised as described for the upper eyelid blepharoplasty, using a clamp and Bovie cautery. The lower eyelid fat pads communicate directly with the deeper orbital fat, so excessive traction on the fat should be avoided to help prevent orbital hemorrhage. The incisions may be left open to heal spontaneously, or loosely applied fast absorbing sutures may be used. If redundant skin is present, it may be excised with the scalpel, and the incision closed with 6-0 fast-absorbing gut sutures (Fig. 30-23).

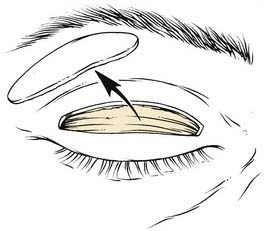

Subciliary Approach

The subciliary approach is most useful for those patients with large amounts of excess skin. A subciliary incision is made 2 mm below the lash line, extending from 1 mm lateral to the inferior punctum to 10-mm lateral to the lateral canthus. The incision extends through the skin and orbicularis muscle along the entire length of the incision (Fig. 30-24). A skin-muscle flap is elevated to the orbital rim, exposing the orbital septum in its entirety. The skin-muscle flap is extended over the rim so that the muscle is separated from the arcus marginalis to allow for proper skin redraping (Fig. 30-25). The orbital septum is then approached either with Bovie cauterization of the intact orbital septum or by excising the bulging orbital fat. After hemostasis is achieved in the fat compartment, a variable amount of skin and muscle is excised as needed (Fig. 30-26). Closure of the incisions is accomplished in two layers. Laterally, the orbicularis fibers are reattached with a 5-0 PDS suture to help prevent tension on the lateral-most aspect of the incisions. This allows the skin edges of the incision to approximate one another closely. Finally, the skin layer is closed with 6-0 fast-absorbing gut suture.13,14

Figure 30-24. The lower eyelid incision may be made with a scissor or with a knife. Care is taken to avoid cutting the eyelashes.

(From Colton JJ, Beekhuis GJ. Blepharoplasty. In: Cummings C, Fredrickson J, Harker L, Krause C, Richardson M, Schuller D, eds. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998:688.)

Complications

Orbital hemorrhage is a complication seen most commonly following lower eyelid blepharoplasty. The presence of orbital hemorrhage is first noted by the patient due to increasing edema, ecchymosis, and severe pain. If vision remains intact, the patient simply has swelling and slight pain, and the bleeding has stopped, then ophthalmology consultation for funduscopic examination and close observation should be done. Occasionally, steroids may be used in combination with mannitol to help reduce the swelling; however, there are no prospective studies showing an advantage to this protocol. If there are signs of optic neuropathy, including severe pain and vision loss, immediate lateral canthotomy with cantholysis, mannitol, and intravenous steroids are instituted. If no resolution ensues, orbital decompression is advised. Failure to address this complication within 90 minutes of onset may result in permanent blindness.16,17

Lagophthalmos, the failure of complete eye closure, is a common finding following upper lid blepharoplasty and ptosis repair. It is frequently seen in the immediate postoperative period due to orbicularis paresis and possibly levator spasm. Over the next few weeks postoperatively, periorbital edema may cause persistence of the lagophthalmos. Such patients should be managed with eye care precautions to prevent corneal exposure complications, including lubrication with ointment at night and artificial tears throughout the day. Additionally, a humidification chamber and taping the eyelids closed may be useful. If lagophthalmos persists beyond 6 to 8 postoperative weeks, an excess of upper eyelid skin may have been removed at the time of surgery. This would require surgical intervention for correction, including the use of a skin graft to replace the missing skin.16,17

Eyelid malposition is one of the most common complications following blepharoplasty, and may range in severity from scleral show to frank lower eyelid eversion. Ectropion and lower eyelid retraction may result from two causes, both of which are common and easy to prevent. Overaggressive skin resection may lead to ectropion because contraction of the shortened lower eyelid anterior lamella may progress to ectropion with wound healing. The second cause of ectropion is a failure to recognize and address excessive lower lid laxity in an effective manner. At the time of blepharoplasty, a lid shortening procedure should be done in cases of excessive lower lid laxity. Failure to perform a lid tightening procedure will result in wound contracture causing lower lid ectropion. Ectropion can usually be corrected by addressing the cause of the problem with either a tarsal strip for excessive laxity or with lysis of cicatricial adhesions that are causing persistence of ectropion.13,14,16,17

Epiphora, in the absence of preoperative dry eye syndrome, is typically the result of a dysfunctional lacrimal collecting system. Causes of a dysfunctional lacrimal apparatus include punctal eversion due to wound contracture or edema, impairment of the lacrimal pump system due to atony, edema, or injury to the orbicularis oculi muscle, or outflow obstruction due to a lacerated canaliculus at the time of incision. If laceration has occurred, placement of a Silastic stent is recommended. Persistent eversion of the lid may be corrected with cauterization or excision of the conjunctival surface below the canaliculus to cause inversion of the lid, punctum, and canaliculus.13,14,16,17

Asymmetry in the early postoperative period may be the result of asymmetric soft tissue edema. If asymmetry persists after the swelling has completely resolved, then using the caliper and excising the appropriate amount of skin and fat will help reestablish symmetry to the lids.13,14,16,17

Adjunctive Procedures

Skin Resurfacing

Facial resurfacing procedures may be used safely in conjunction with surgery to the periorbital area. They produce their effects by ablating skin to variable depths, allowing for collagen regeneration and skin tightening. Different agents and techniques produce varying degrees of penetration and results. Even though resurfacing cannot replace surgery for the treatment of deep hyperfunctioning rhytids, laser, chemical peels, and dermabrasion may be used to treat fine wrinkling, acne scarring, telangiectasias, and photodamaged skin. Care should be exercised when resurfacing skin that has been undermined in the immediate subcutaneous plane for fear of devascularizing the tissue, resulting in flap necrosis. The resurfacing should be feathered into the hairline and eyebrows to avoid evident lines of demarcation. Birth control pills should be stopped 2 months before facial resurfacing to prevent pigment changes. Accutane (isotretinoin) should not have been used in the year preceding skin resurfacing to avoid the increased risks of hypertrophic scarring associated with isotretinoin use. An antiviral agent is prescribed by many physicians for use during the periprocedure period as prophylaxis against herpetic reactivation. Preoperative tretinoin is thought by many to accelerate wound healing.18

Milia, 1- to 2-mm pustules originating from the skin adnexa, are frequent following resurfacing procedures. They often resolve without treatment, but if they persist they may be unroofed with a scalpel or 18-gauge needle. Failure to treat the milia may result in permanent scar formation. Pigmentary changes are expected following resurfacing procedures; however, they should resolve by 4 to 6 weeks. If the erythema associated with the resurfacing procedure seems to be excessive, topical steroids may be applied to reduce the erythema. Prolonged discoloration occurs most commonly in patients with Fitzpatrick IV-VI skin types, and may be the result of sun exposure in the period following resurfacing. Persistent hyperpigmentation may require bleaching with hydroquinone or retinoic acid, whereas hypopigmentation may require serial excision and punch graft replacement of the discolored skin. There are no data at present to suggest that pretreatment with any topical agent will help prevent post-resurfacing pigment changes.18

Botox

Botulinum exotoxin A (Botox), produced by the bacteria Clostridium botulinum, is useful in reducing facial wrinkles associated with facial muscle contractions. Botox is safe, easy to administer, and reversible with time, making it a very attractive cosmetic adjunct in the treatment of the periorbital region. It reversibly blocks the release of acetylcholine from the presynaptic neuromuscular junction, thereby temporarily paralyzing the affected muscle. The effects of Botox are observed 2 to 3 days after injection, with maximal weakness occurring 1 to 2 weeks after injection. The effects last for 3 to 6 months. Botox is useful for the treatment of glabellar frown lines, crow’s feet, horizontal forehead rhytids, smile lines, horizontal neck lines, and unilateral facial paralysis to reduce the asymmetry between the normal and paralyzed side. Botox may also be used as a browlift procedure. Injection into the orbicularis oculi muscle inferior to the lateral brow allows for unopposed frontalis muscle action, which produces brow elevation. Similarly, frontalis injection along the medial aspect of the brow allows for unopposed orbicularis muscle activity, producing a slight ptosis of the medial brow and a relative elevation of the lateral brow. Complications from Botox use include ptosis and lagophthalmos with inadvertent injection of deeper muscles. Additionally, erythema and bruising may occur.19

Fagien Fagien S. Putterman’s Cosmetic Oculoplastic Surgery, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

Tyers Tyers AG, Collin JRO. Colour Atlas of Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery with DVD, 3rd ed. Butterworth-Heinemann; 2007.

Mauriello Mauriello JA. Techniques in Cosmetic Eyelid Surgery: A Case Study Approach. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004.

1. Gilchrest BA. Skin and photoaging: an overview. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:610.

2. Ellis CN. Management of aging skin. In: Cummings C, Fredrickson J, Harker L, Krause C, Richardson M, Schuller D, editors. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998:629.

3. Sherris DA, Otley CC, Bartley GB. Comprehensive treatment of the aging face—cutaneous and structural rejuvenation. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:139.

4. Bergin DJ. Anatomy of the eyelids, lacrimal system, and orbit. In: McCord CD, Tanenbaum M, Nunery WR, editors. Oculoplastic Surgery. New York: Raven Press; 1995:51.

5. Howard BK, Leach J. Aesthetic Surgery of the Upper Third of the Face. A Self Instructional Package. Washington, DC: American Academy of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, Inc; 1998.

6. Kikkawa DO, Lemke BN. Orbit and eyelid anatomy. In: Dortzbach RK, editor. Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery: Prevention and Management of Complications. New York: Raven Press, 1994.

7. Quatela VC, Graham D, Sabini P. Rejuvenation of the brow and midface. In: Papel I, Frodel J, Holt G, et al, editors. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2nd ed. New York: Thieme; 2002:171.

8. Hamra ST. The deep plane rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:53.

9. Hamra ST. Composite rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:1.

10. Koch RJ, Troell RJ, Goode RL. Contemporary management of the aging brow and forehead. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:710.

11. Pastorek NJ. Upper lid blepharoplasty. In: Papel I, Frodel J, Holt G, et al, editors. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2nd ed. New York: Thieme; 2002:185.

12. Moses JL, Tanenbaum M. Blepharoplasty: cosmetic and functional. In: McCord CD, Tanenbaum M, Nunery WR, editors. Oculoplastic Surgery. New York: Raven Press; 1995:285.

13. Rankin BS, Arden RL, Crumley RL. Lower eyelid blepharoplasty. In: Papel I, Frodel J, Holt G, et al, editors. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2nd ed. New York: Thieme; 2002:196.

14. Colton JJ, Beekhuis GJ. Blepharoplasty. In: Cummings C, Fredrickson J, Harker L, Krause C, Richardson M, Schuller D, editors. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998:676.

15. Cook TA, Dereberry J, Harrah ER. Reconsideration of fat pad management in lower lid blepharoplasty surgery. Arch Otol. 1984;110:521.

16. Castanares S. Complications in blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1978;5:149.

17. Adams BJS, Feurstein SS. Complications of blepharoplasty. Ear Nose Throat J. 1986;65(1):11.

18. Alster TS, Lupton JR. Treatment of complications of laser skin resurfacing. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2000;2:279.

19. Binder WJ, Blitzer A, Brin MF. Treatment of hyperfunctional lines of the face with botulinum toxin A. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:1198-1205.

20. Millay DJ, Larrabee WF. Ptosis and blepharoplasty surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;115:198-201.