CHAPTER 51 Blepharoplasty

Anatomy

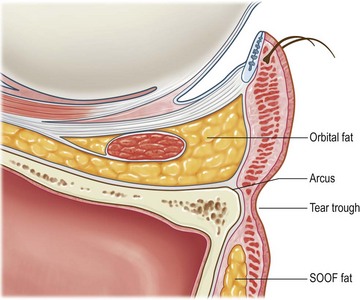

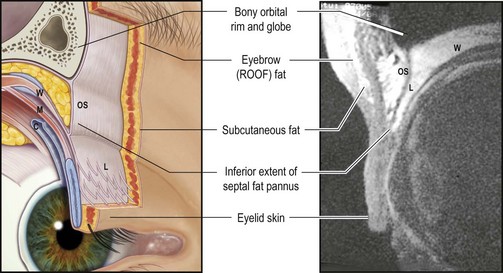

It is important to develop the ability to ‘see through’ the skin and subcutaneous tissues that drape over the deep anatomic substrates of the periorbital area. The surgeon should get a sense of the contribution of these various substrates to the existing surface anatomy, and therefore a sense of which substrates are available for surgical modification. An understanding of the three-dimensional contours in this area, the contribution of soft tissue and bone, and how they can be enhanced is key in blepharoplasty surgery. Figure 51.1 demonstrates the important characteristics of surface anatomy. Skin and subcutaneous tissues can be excised to reduce redundancy, and fat can be removed to expose the deeper structures, such as the levator aponeurosis and bony orbital rim.

Fig. 51.1 Sagittal section of upper eyelid anatomy.

From Goldberg RA, Wu JC, Jesmanowicz A, et al. Eyelid anatomy revisited. Dynamic high-resolution magnetic resonance images of Whitnall’s ligament and upper eyelid structures with the use of a surface coil. Arch Ophthalmol 1992;110:1598–600, with permission.

The contour of the tightly attached skin over the levator aponeurosis and tarsus forms the eyelid ‘platform,’ which we call the ‘tarsal platform show’. The septal fat pannus overlies the levator and upper tarsal plate. Racial variations exist, and are important here. At one extreme lies the Asian patient, with an abundant septal fat pannus consisting of skin, subcutaneous eyelid and eyebrow fat that covers the entire tarsal plate, and essentially obliterates any visible platform. At the other extreme lies the aged Caucasian patient with superior sulcus fat atrophy, in which case the entire levator can often be followed up into the orbit, sometimes even with Whitnall’s ligament exposed as a horizontal band just below the orbital rim (Fig. 51.2A and B).

The most medial portion of the upper eyelid, combined with the lateral surface of the nose and the medial canthus, constitutes an area that deserves particular attention. Redundancy in this area is often related to eyebrow ptosis, with tissues encroaching from the glabella to form a diamond-shaped deformity. We can see these changes in a composite photograph of a woman at age 25 and age 75 (Fig. 51.3). This anatomically complex area has different tissue characteristics from the interdigitation of different skin textures. Incisions should not extend into this area because of the high potential of producing postoperative webs or other irregularities that give an esthetically unpleasant outcome (Fig. 51.4). Elevation of the redundant eyebrow tissues out of the multicontoured space, for example through endoscopic forehead lift, is often more effective in restoring the normal width of the radix and improving the contours in the multicontoured medial eyelid space.

The lower eyelid is composed of skin and underlying orbicularis muscle, which continues past the lower orbital rim onto the face. Behind the orbicularis, near the lid margin, is the tarsal plate. The orbital septum fuses with the inferior border of the tarsus and continues caudally to attach to the crest of the lower orbital rim at the arcus marginalis. Just behind the orbital septum are the lower eyelid orbital fat compartments. The orbital fat is bordered posteriorly and superiorly by the lower eyelid retractors, which arise from the inferior rectus muscle and tendon. The lower lid retractors fuse with the orbital septum approximately 5 mm inferior to the inferior tarsal border before inserting onto the tarsal plate. Posteriorly, the lower eyelid retractors are closely adherent to the palpebral conjunctiva of the lower lid (Fig. 51.5).The orbital fat is surrounded by many fine connective tissue septae (septae of Koorneef). A fascial extension of the sheath of the inferior oblique muscle and Lockwood’s ligament called the arcuate expansion inserts on the inferolateral orbital rim and separates the central from the lateral fat compartments. The inferior oblique muscle originates from the anterior medial orbital floor and separates the medial fat compartment from the central fat compartment as it passes posteriorly and laterally beneath the equator of the globe. The lateral fat compartment lies more posteriorly, the central fat compartment lies more anteriorly, and the medial fat compartment is paler in color. As shown in Figure 51.5, the orbital fat can be easily accessed by incising the conjunctiva and lower lid retractors in the fornix while the orbital septum remains well anterior to these structures.

Eyelid assessment: fundamental principles and surgical planning

Upper blepharoplasty

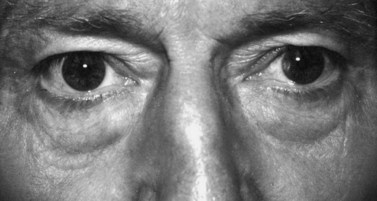

Upper eyelid fullness is generally a congenital condition (Fig. 51.6A). It can be addressed by removal of fat from the upper eyelid, exposing the underlying levator aponeurosis and tarsus (Fig. 51.6B, presurgery and C, postsurgery). The surgeon must recognize when the fullness in the eyelid complex is caused by eyebrow descent. The eyebrows are held at a certain position by the tone of the frontalis muscle, which maintains comfortable vision. If heavy tissues are removed from below the brow, it will descend to its resting position (Figs 51.7 and 51.8).

If too much of the septal fat pannus and ROOF (retro-orbicularis oculi fat or eyebrow fat pad) is removed, the underlying structures will be exposed to an undesirable degree (Fig. 51.9A and B). As already mentioned, excessive hollowness of the superior sulcus gives an aged appearance to the eyelid complex. Blepharoplasty in the thin aged upper eyelid must be conservative, with minimal removal of fat. Because there will not be much of a septal fat pannus or eyelid fold to cover the incision, the crease is often made high in the eyelid where it will fall into the shadow of the superior sulcus and be relatively hidden.

If the globe is relatively prominent, the tarsal platform show will be more readily exposed by removing orbital fat (Fig. 51.10). The orbital fat and full eyelid tissues actually benefit the patient by masking underlying proptosis. In this situation the admonition ‘big eye, big trouble’ should be heeded, and fat removal should be conservative or even avoided altogether, perhaps in favor of orbital decompression for proptosis reduction.

Racial variations are also significant in planning and executing upper blepharoplasty. For example, compared with the Occidental configuration, the Oriental eyelid is characterized by a full, sometimes bulging superior sulcus and a low crease with narrow or absent tarsal platform. The crease narrows medially to form an epicanthal fold. The fullness is based anatomically on abundant and somewhat fibrotic fat in the subcutaneous, suborbicularis, and postaponeurotic spaces. This abundant fat can be carefully sculpted because it is fibrotic, but it is unforgiving, so it is easy to create a contour abnormality, a visible dent, or an undesired second crease if the fat is not evenly, or conservatively, sculpted. The goal of Asian blepharoplasty is usually to retain the full characteristic of the eyelid while better defining the thin tarsal platform show. To accomplish this, conservative debulking of the inferior edge of the septal fat pannus (with sparing and avoidance of the remainder) is performed. Fixation of the orbicularis or skin edge to the exposed tarsus can also be performed to create a firm, low, and meticulously symmetric crease (Fig. 51.11A and B).

Lower blepharoplasty

Lower blepharoplasty addresses the contours of the lower eyelid and cheek. When evaluating patients for possible lower eyelid surgery, the contours of the orbital fat should be observed. Often the medial, central, and lateral fat pads can be identified and individually graded (Fig. 51.12). This type of analysis helps with surgical planning. Inferior to the fat pads, the orbital rim can be seen as a groove marking the arcus marginalis, or orbital septal insertion. There exists an orbitomalar ligament that folds the skin. Medially, the groove can be quite prominent and is often referred to as the ‘tear trough deformity’. Inferior to the groove of the orbital rim, the cheek fat forms various contours over the face of the maxilla and malar prominence. Descent of the SOOF fat pad gives rise to a hollow region below the orbital rim that is bordered inferiorly by a visible trailing edge of the descended SOOF fat pad. Young patients may have a congenitally prominent tear trough deformity.

Procedures: upper blepharoplasty

Designing and marking the eyelid crease

In a more typical patient, a certain amount of the septal fat pannus will hang over the surgical incision, and therefore the inferior incision is drawn slightly higher than the height of the desired tarsal platform. In a woman, this will typically result in a lower incision, approximately 7–10 mm above the eyelash line centrally (Fig. 51.13). And in a man, an incision typically 5–8 mm above the lash line is indicated. In an Asian patient, the range might be 3–6 mm above the eyelash line centrally. Laterally, the incision dips down to pick up some of the temporal hooding. It is best to address this temporal hooding through eyebrow elevation, but if eyebrow surgery cannot be performed, or if redundant tissue persists after eyebrow elevation, temporal hooding can be excised directly at the expense of a scar in the thicker skin of the temple and at the expense of decreasing the distance between the tail of the brow and the lateral eyelid. Medially, it is also best to elevate redundant tissue out of the multicontoured area (the medial one fifth of the upper eyelid) through appropriate eyebrow elevation. However, if the surgeon elects to compromise and remove redundant skin in this area directly, a ‘lazy S’ incision helps to decrease webbing in this susceptible region by converting the vector of skin tension (upon closure) to a more horizontal direction. This incision is accomplished by dipping down the most medial component of the incision to pick up the medial redundancy. The proliferation of creative flaps such as W-plasties and T-shaped incisions is indicative of the difficulty encountered by surgeons working in the medial canthal region. It is not uncommon to see early web formation, even preoperatively, and any surgery that removes tissue in the medial canthal region is prone to web formation. Web formation is caused primarily by the tendency for the scar to contract, and to ‘clothesline’ the tissues from the nasal bridge across the hollowed concave region of the medial canthal multicontoured surface (see Fig. 51.4). The more the surgeon can lift these tissues out of the multicontoured area through eyebrow surgery, and avoid the temptation to draw the medial canthal incision line far into the multicontoured area, the less chance there is of web formation and other contour problems in this region.

In upper blepharoplasty, the vertical excision of skin should always be conservative. Flowers has suggested that at least 1 inch (25 mm) of skin between the eyebrow and eyelashes is necessary for proper eyelid closure. Certainly, older techniques, such as the ‘skin pinch,’ in which the surgeon tries to maximize skin removal while narrowly avoiding lagophthalmos, are philosophically and technically inappropriate. Rather, the goal should be just the opposite: How little skin can we remove from the lid and still accomplish our surgical goal of creating an eyelid platform while sculpting the eyelid tissues to reveal more of the underlying deep structures? In our experience, we leave at least 20 mm of total skin between the eyelid margin and inferior brow skin. Keep in mind, female patients may pluck their brow hairs and this may not be the true inferior extent of the brow; rather keep in mind the transition from the thick brow skin to the thin eyelid skin as the inferior extent of the brow skin. We have had good results with this and of course it can be customized to the individual patient’s needs. In the presence of uncorrected eyebrow ptosis, the surgeon has to be especially careful to avoid the temptation to address heavy eyebrow tissues by excising them from below, in the eyelid space. This can create a situation in which the ‘eyebrows are sutured to the eyelids’, so that the patient is functionally and esthetically crippled with persistence of heavy eyebrow tissues in the eyelid space and an inability to elevate the eyebrows without creating lagophthalmos (see Figs 51.7 and 51.8). Very rarely is it necessary to excise more than 10 mm of skin in the vertical direction. Typically, a 5–7 mm excision is appropriate, and an excision of 3–5 mm of skin is not uncommon, especially in younger patients.

Surgical technique

In most instances the cutaneous flap is removed in one piece, leaving much or most of the orbicularis intact (Fig. 51.14). In some patients with full eyelids, a small strip of orbicularis can be debulked; care must be taken not to remove too much orbicularis.

The orbital septum is incised horizontally (Fig. 51.15), usually across the full extent of the upper eyelid to provide an ‘open-sky’ approach to the underlying structures. The septum is not a single layer as is usually described, but rather, a multilaminar structure with varying thickness in different areas of the upper eyelid. As Flowers has suggested (see Further reading), the orbital septum should be opened just above its insertion into the aponeurosis, with particular attention to avoiding accidental sectioning of the underlying aponeurosis. The preaponeurotic fat pads will be viewed next. Most of the fullness of the upper eyelid is the result of herniation of the larger central fat pad, but occasionally the smaller nasal fat pad can contribute to significant and localized bulging. The fat that was preoperatively planned for reduction is removed (Fig. 51.16). This can be accomplished in a piecemeal fashion when using electrocautery by alternating the cautery and coagulation. Alternatively, fat vaporization can be accomplished with the CO2 laser. Excessive pulling on the fat pads should be avoided to prevent avulsion of the orbital vessels that usually run within these fat compartments. In some individuals there is excessive fullness at the lateral aspect of the upper lid as a result of involutional stretching and descent of the lacrimal gland into the preaponeurotic tissue plane. Obviously, it is important to identify the more orange-looking friable lacrimal gland tissue, and to avoid its amputation. The lacrimal gland can be repositioned inside the lacrimal gland fossa and sutured to the overlying periosteum.

To reiterate, it is important to avoid excessive reduction of the preaponeurotic fat pads. Its ease of removal with the ‘open-sky’ approach should never lead to excessive removal. Enough fat should be left to serve as a physiologic sliding tissue for upper eyelid excursion. Sometimes, fat repositioning is all that it is required. The ‘valley’ of the superior oblique tendon separates the central fat pads from the nasal fat pads, and it is usually a hollow area (Fig. 51.17). Fat repositioning into this area can reduce the inverted ‘V’ deformity that characterizes the aged eyelid.

Fig. 51.17 The medial fat pad is white in color. It lies medial to the valley of the superior oblique muscle.

After the judicious removal of preaponeurotic fat, the septal edge can be trimmed to provide a flatter, smoother, and tighter upper eyelid platform (Fig. 51.18). This step can be supplemented with excision of a strip of pretarsal orbicularis oculi muscle along the inferior edge of the incision for further debulking of the pretarsal area. The CO2 laser is an excellent instrument that can vaporize and tighten these preaponeurotic tissues to create a tight platform and a well-defined eyelid crease.

The last step of the procedure, wound closure, includes the consideration of supratarsal fixation. The preoperative planning will determine whether a well-defined ‘hard’ crease or a more conspicuous ‘soft’ crease is desirable. Generally, a ‘hard’ crease is optimal for women to provide a well-demarcated upper eyelid platform for the application of eye shadow, whereas most men do not benefit from such an abrupt definition of the upper eyelid crease. When supratarsal fixation is performed, the skin and orbicularis oculi muscle of the pretarsal flap along the inferior edge of the incision are anchored together to the ‘leathery’ preaponeurotic fascia at the level of the superior portion of the tarsus. The exact anchoring level varies with each patient and is another manifestation of the individualization that is required in blepharoplasty surgery. Several interrupted sutures can be placed for supratarsal fixation, or a running suture that is used for skin closure can include a purchase of the preaponeurotic fascia (Fig. 51.19). A 6-0 or 7-0 running absorbable or non-absorbable suture on a cutting needle can be used to close the cutaneous incision; some surgeons insist on a subcuticular running closure, but we have not noticed any difference in wound healing or postoperative appearance.

Procedures: lower blepharoplasty

Surgical technique

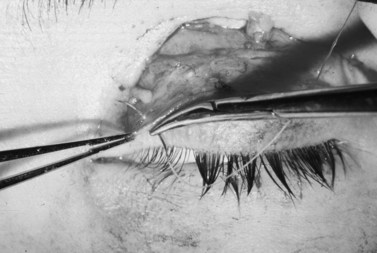

The conjunctiva and lower lid retractors are incised directly over the fat with the needle tip directed 1–2 mm posterior to the inferior orbital rim. The incision may be made from medial to lateral beginning at the apex of the caruncle and extending to the lateral canthus, if necessary, to expose the lateral fat. The incision should be made at least 4 mm inferior to the inferior punctum to avoid damage to the canaliculus. An alternative technique is to make several small (5–7 mm) incisions over the individual fat pockets and connect them as necessary for full exposure. It is important to be at least 4 mm inferior to the inferior tarsal border when incising the conjunctiva and lower lid retractors. After incising the conjunctiva and lower lid retractors, yellow orbital fat can be seen bulging into the field (Fig. 51.20).

Laterally, the arcuate expansion of the inferior oblique muscle separates the central fat pocket from the lateral fat pocket (Fig. 51.21). Incision of this fascial band at its attachment to the orbital rim, with scissors or cutting cautery, makes the central fat pocket continuous with the lateral fat pocket. This permits identification and exposure of the lateral fat pocket. The lateral fat pad is covered with more septae than the central pad and may not spring forward as easily. Importantly, it is located superiorly in the orbit, often at the level of the lateral canthal tendon, so that exposing the inner lateral orbital wall with blunt dissection helps expose the lateral fat pad. With excision of the superficial portion of the lateral pad, the fat posterior to this point comes forward more freely.

The medial fat compartment is the most difficult to locate, and partial resection of the central fat may be necessary to allow identification of the medial fat. Of note medially, the inferior oblique muscle separates the central and medial fat compartments. It is important to identify this ‘valley’, especially for the surgeon who is learning this technique. Early identification will ensure that both the medial and central fat compartments are excised, and will avoid injury to the inferior oblique muscle. After identification and exposure of the central fat, which lies most anteriorly of the three fat pads, the medial fat may be totally obscured, or may present as a slight bulge in the superior medial aspect of the wound. The glass lid plate can be replaced at this point and pressure placed on the globe to ballotte the fat forward. The needle tip can be used to sharply dissect the overlying septae and the tenotomy scissors used to gently blunt dissect the fat pad. The medial fat is different from the central and lateral fat in that it appears white and membranous (Fig. 51.22). Additionally, it may not be postseptal at all; rather, it may come from the muscle cone, bulging around the edge of the lower eyelid retractors. The only difference between the lower eyelid medial fat pad and the medial fat pad in the upper lid is that the palpebral vessels go directly through the medial fat pad, as opposed to the upper eyelid where the medial vessels lie on the surface of the fat pad. Once the central and medial fat pads are excised, the inferior oblique muscle will be in plain view.

With advanced techniques, the medial fat pad can be sculpted into a pedicle that can then be transposed outside the orbit along the inferior orbital rim to fill in the tear trough deformity. The orbital septum is opened along the arcus marginalis, and the fat pedicle is arranged in a supraperiosteal, suborbicularis pocket (Fig. 51.23A–D).

After excising the fat, the lower lid margin is pulled superiorly to release any adhesions that might result in lid retraction, as well as to realign the tissue planes (Fig. 51.24). With the lid on stretch, gentle pressure on the globe reveals any residual fat bulges. If necessary, further fat can be excised at this point. In our experience, it is not necessary to close the conjunctiva and lower lid retractors; however, a single interrupted suture of 6-0 mild chromic gut is used to close the conjunctiva centrally if the tissues do not appear well opposed.

Summary

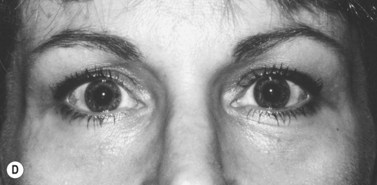

Most blepharoplasty patients seek eyelid surgery because of age-related changes in the eyelid complex, while a minority are young, with ‘undesirable’ congenital characteristics. The aging process in the eyelid complex is characterized by skin texture changes (with loss of elasticity and formation of wrinkles), enophthalmos (due to loss of fat), and lower eyelid fat prolapse (with inferior displacement of fat). Upper eyelid blepharoplasty is not a matter of skin removal; rather, it involves sculpturing and contouring of the esthetic unit. Transconjunctival lower eyelid blepharoplasty is extremely effective at reducing lower eyelid ‘bags’ caused by prolapsed orbital fat. The anterior–posterior blepharoplasty, consisting of transconjunctival lower blepharoplasty (or repositioning) and laser resurfacing is, in our hands, one of the most successful surgical procedures in facial esthetic surgery. The blepharoplasty surgeon should avoid excessive fat removal. Instead, the focus should be on conservative fat removal, with or without fat repositioning. Total awareness will lead to successful rejuvenation of the aging eyelid complex. In addition, successful rejuvenation may not require (or indeed benefit from) surgery, and use of adjunctive methods such as hyaluronic acid gel fillers and botulinum toxin may be considered for restoration of the three-dimensional contours (Fig. 51.25).

Aiache AE, Ramirez OH. The suborbicularis oculi fat pads: An anatomic and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:37-42.

Baylis HI, Sutcliffe T, Fett DR. Levator injury during blepharoplasty. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:570-571.

Baylis HI, Long JA, Groth MJ. Transconjunctival lower eyelid blepharoplasty: Technique and complications. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:1027-1032.

Baylis HI, Wilson MC, Groth MJ. Complications of lower blepharoplasty. In: Putterman AM, editor. Cosmetic Oculoplastic Surgery. 2nd edn. Philadelphia (PA): WB Saunders; 1993:356-388.

Dresner SC, Karesh JW. Transconjunctival entropion repair. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:1144-1148.

Edgerton MTJr. Causes and prevention of lower eyelid ectropion following blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972;49:367-373.

Flowers RS. Periorbital aesthetic surgery for men. Eyelids and related structures. Clin Plast Surg. 1991;18:689-729.

Flowers RS. Optimal procedure in secondary blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:225-237.

Flowers RS. Canthopexy as a routine blepharoplasty component. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:351-365.

Flowers RS, Caputy GG, Flowers SS. The biomechanics of brow and frontalis function and its effect on blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:255-268.

Flowers RS. Upper blepharoplasty by eyelid invagination. Anchor blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:193-207.

Flowers RS, Flowers SS. Precision planning in blepharoplasty. The importance of preoperative mapping. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:303-310.

Flowers RS, Flowers SS. Diagnosing photographic distortion. Decoding true postoperative contour after eyelid surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:387-392.

Goldberg RA, Shorr N, Marmor MF, et al. Blindness following blepharoplasty: Two case reports, and a discussion of management. Ophthal Surg. 1990;21:85-89.

Goldberg RA. Transconjunctival orbital fat repositioning: transposition of orbital fat pedicles into a subperiosteal pocket. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(2):743-748. discussion 9-51

Goldberg RA, Fiaschetti D. Filling the periorbital hollows with hyaluronic acid gel: initial experience with 244 injections. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22(5):335-341. discussion 341–3

Hamako C, Baylis HI. Lower eyelid retraction after blepharoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;9:517-521.

Jelks GW, Jelks EB. Preoperative evaluation of the blepharoplasty patient. Bypassing the pitfalls. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:213-223.

Koornneef L. Spatial aspects of orbital musculo-fibrous tissue in man: a new anatomical and histological approach. Amsterdam: Swets & Zeitlinger; 1977. p. 1–168

Lambros V. Observations on periorbital and midface aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(5):1367-1376. discussion p. 1377

Levine MR, Boyton J, Tenzell RR, et al. Complications of blepharoplasty. Ophthal Surgery. 1975;6:53-57.

May JWJr, Fearon J, Zingarelli P. Retro-orbicularis oculus fat (ROOF) resection in aesthetic blepharoplasty: A 6-year study in 63 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:682-689.

McKinney P, Zukowski ML, Mossie RD. The fourth option: A novel approach to lower lid blepharoplasty. Aesth Plast Surg. 1991;15:293-296.

Neuhaus RW. Lower eyelid blepharoplasty. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:1100-1109.

Palmer FR, Rice DH, Churukian MM. Transconjunctival blepharoplasty complications and their avoidance: A retrospective analysis and review of the literature. Arch Head Neck Surg. 1993;119:993-999.

Parkes M, Fein W, Brennan HG. Pinch technique for repair of cosmetic eyelid deformities. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973;89:324-328.

Perman KI. Upper eyelid blepharoplasty. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:1096-1099.

Sheen JH. Supratarsal fixation in upper blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974;54:424-431.

Syniuta LA, Goldberg RA, Thacker NM, et al. Acquired strabismus following cosmetic blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(6):2053-2059.

Suh CD. Laser double eyelid operation. Aesth Plast Surg. 1999;23:343-348.

Sutcliffe T, Baylis HI, Fett DR. Bleeding in cosmetic blepharoplasty: An anatomical approach. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;1:107-113.

Tomlinson FB, Hovey LM. Transconjunctival lower blepharoplasty for removal of fat. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;56:314-318.

Warwick R. Eugene Wolff’s Anatomy of the Eye and Orbit: Including the Central Connections, Development and Comparative Anatomy of the visual Apparatus, 7th edn. Philadelphia (PA): WB Saunders; 1976.