Bladder and Urethra

Urachal Anomalies

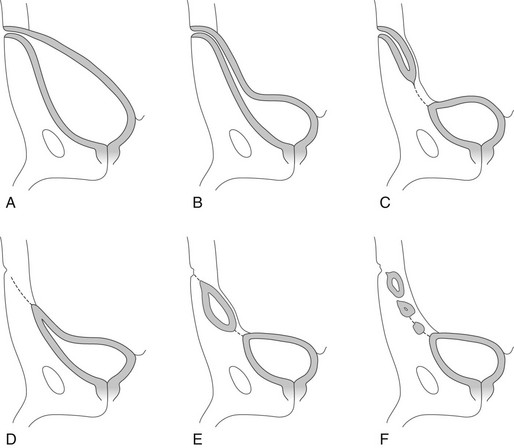

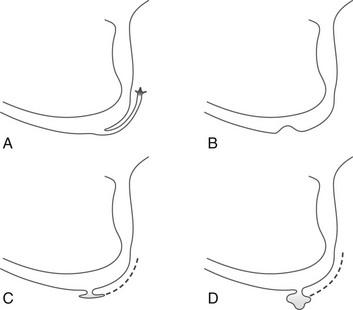

Overview: Fibrotic regression of the urachus typically extends from the umbilicus toward the bladder, resulting in the formation of the median umbilical ligament.1,2 Failure of the urachus to normally regress results in one of four disorders: (1) patent urachus (50%), (2) urachal sinus (15%), (3) urachal diverticulum (3-5%), and (4) urachal cyst (30%) (Fig. 121-1).3 Clinical symptoms include umbilical discharge, local infection, lower abdominal pain, and urinary tract infection.4

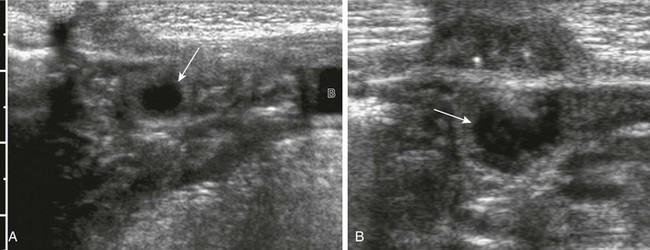

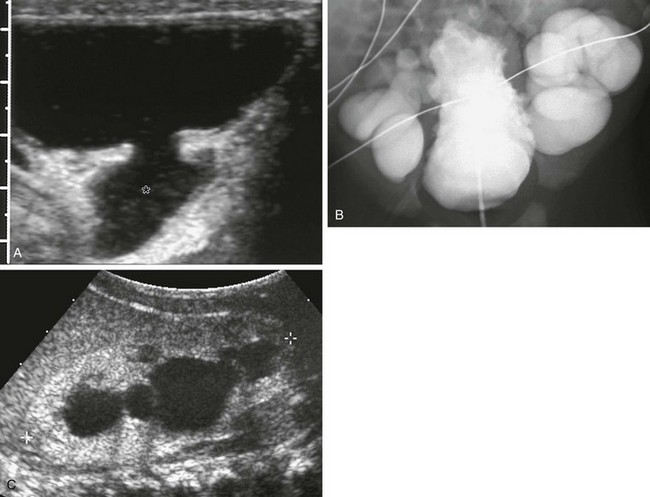

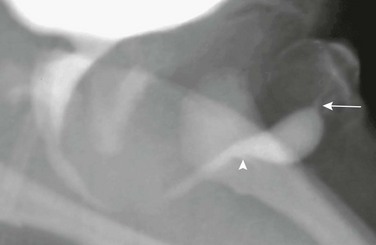

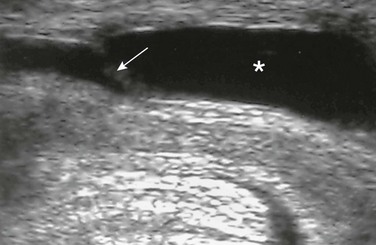

Imaging: Abdominal ultrasound, voiding cystourethrography (VCUG), and fistulography are the primary imaging diagnostic tools for initial evaluation of suspected urachal anomalies.5 In a patent urachus, the urachus fails to obliterate, resulting in a vesicoumbilical fistula (Fig. 121-2). The diagnosis may be confirmed by catheterization of the bladder through the umbilicus (Fig. 121-3) or by VCUG with films in the lateral projection. In urachal sinus, the urachus is closed at the level of the bladder but remains patent at the umbilicus (e-Fig. 121-4). The diagnosis of urachal sinus can be made only by catheterization and opacification of the umbilical fistula. In urachal diverticulum, the urachus is obliterated at the level of the umbilicus but communicates with the bladder. Ultrasound readily demonstrates this, but urachal diverticula are best shown on a cystogram in the lateral projection (Fig. 121-5). In urachal cyst, the urachus is obliterated at both ends but remains patent in its midportion. Multiple small urachal cysts may occur as a result of segmental urachal obliteration (e-Fig. 121-6).1

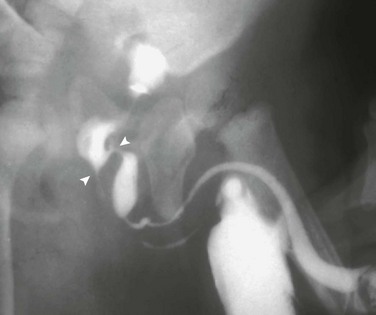

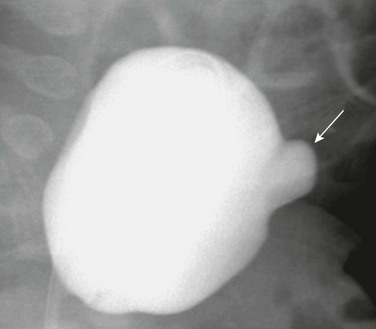

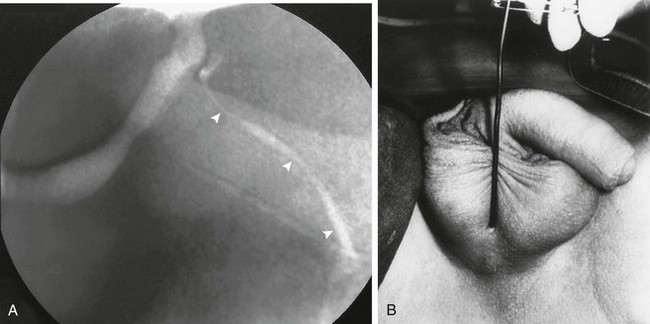

Figure 121-2 Patent urachus.

A, Lateral view during a voiding cystourethrogram shows a fistulous tract (arrow) leading from the dome of the bladder to the umbilicus. B, Longitudinal sonogram shows a urine-filled patent urachus (arrowheads) extending from the dome of bladder (B) to the umbilicus (arrow).

Figure 121-3 Patent urachus.

Lateral view during voiding cystourethrography performed after catheterization of the bladder through the umbilicus (arrow).

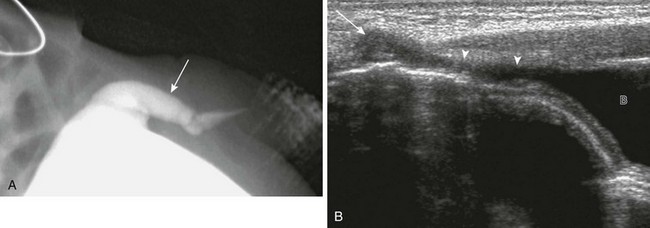

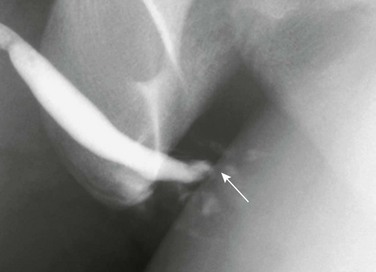

Figure 121-5 Urachal diverticulum.

Lateral view during a voiding cystourethrography shows a urachal diverticulum extending from the bladder dome (arrow).

Bladder Diverticula

Overview: Bladder diverticula, which may be primary (congenital), secondary, or iatrogenic (postoperative) (Box 121-1),7 are the most common, are seen more often in males than in females, may be single or multiple, and occur most frequently in the trigonal area.8,9 Secondary bladder diverticula are the result of chronically increased intravesical pressure and occur most commonly in the paraureteral area. Iatrogenic diverticula are seen most often in the anterior wall of the bladder at the site of a previous vesicostomy or suprapubic drainage catheter, and at the ureterovesical junction after ureteral reimplantation. Patients present with recurrent urinary tract infection, urinary retention, incontinence, stone formation, vesicoureteral reflux, and ureteral and bladder outlet obstruction.10

Imaging: VCUG is the most efficient method of detection.11 Bladder diverticula may become visible only during voiding when contractions of the bladder force urine into the diverticulum (Fig. 121-7). A paraureteral diverticulum or Hutch diverticulum12 is located laterally and cephalad to the ureteral orifice (e-Fig. 121-8). If the diverticulum is large, it may engulf the ureteral meatus and the ureter may empty into the diverticulum. Associated vesicoureteral reflux is present in about half of the cases (e-Fig. 121-9).13

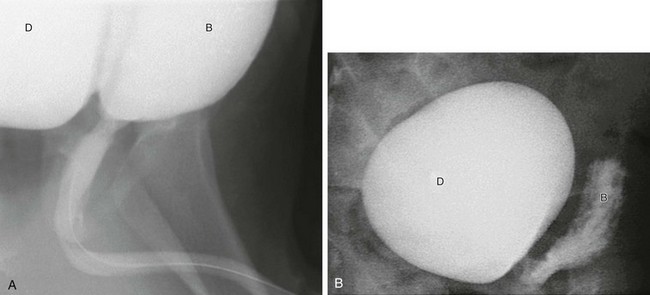

Figure 121-7 Expanding diverticulum.

A, Oblique view during voiding cystourethrography showing an expanding right bladder diverticulum (D) during voiding. B, bladder. B, At the end of voiding, a large contrast medium–filled diverticulum (D) remains with an empty bladder (B).

Neoplasms of the Bladder

Overview: Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is the most common and important neoplasm of the lower genitourinary tract and accounts for about 20% of all RMS seen in children. RMS is the most frequent bladder neoplasm in children in the first two decades of life, presenting typically at ages 2 to 6 years or 15 to 19 years.17,18 In males, more than 50% of the cases arise from the prostate. In females, RMS arises from the vagina and the uterine cervix. Histologically, the tumor is divided into three subtypes: (1) embryonal, (2) alveolar, and (3) polymorphic. Embryonal RMS is further subdivided into three categories: (1) classic embryonal, (2) botryoid, and (3) spindle cell. The embryonal form is, by far, the most common, accounting for approximately 90% of all RMS. The embryonal botryoid subtype accounts for one fourth of the cases and has a lobulated, polypoid appearance, resembling a bunch of grapes, hence the name sarcoma botryoides.17,19–21

RMS spreads by local extension from the bladder, prostate, and vagina into regional and retroperitoneal lymph nodes and muscle. Lymph node involvement or distant tumor spread is found at initial diagnosis in 10% to 20% of patients.22 Although RMS can metastasize to almost any site, it does so most commonly to the lungs, cortical bone, and lymph nodes, and less frequently to the bone marrow and liver. Hematuria, dysuria, frequency, urinary retention, and obstruction are the most frequent clinical manifestations. An abdominal mass may be palpated in some cases. In females, a vaginal tumor may manifest as a prolapsing mass in the introitus.19

Imaging: On ultrasound, RMS is hyperechoic or hypoechoic, compared with surrounding healthy tissue, with or without focal anechoic regions representing necrosis and hemorrhage. Color and duplex Doppler evaluation show hypervascularity.22 VCUG shows a filling defect in the posteroinferior aspect of the bladder (e-Fig. 121-10). When originating in the prostate (Fig. 121-11 and e-Fig. 121-12), the cystogram shows an upward displacement of the bladder floor or a smooth, lobulated mass at the base of the bladder.19,22 Contrast-enhanced CT identifies RMS of the prostate or bladder base as a bulky pelvic mass of heterogeneous attenuation that may invade periurethral and perivesical tissues or may extend into the ischiorectal fossa. Calcification is rare. Vaginal tumors often arise high in the anterior vaginal vault and may be indistinguishable from a primary bladder tumor.19 On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, RMS demonstrates nonspecific, low signal intensity on T1-weighted sequences and high signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences. After the administration of MRI contrast, RMS typically enhances heterogeneously.

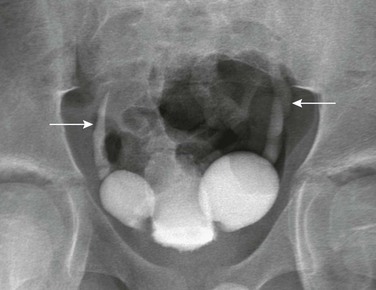

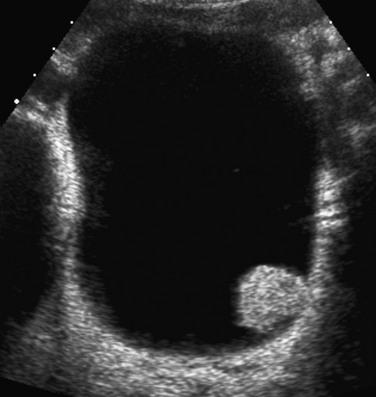

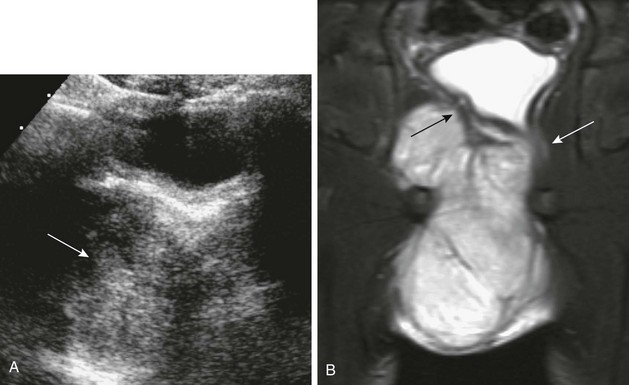

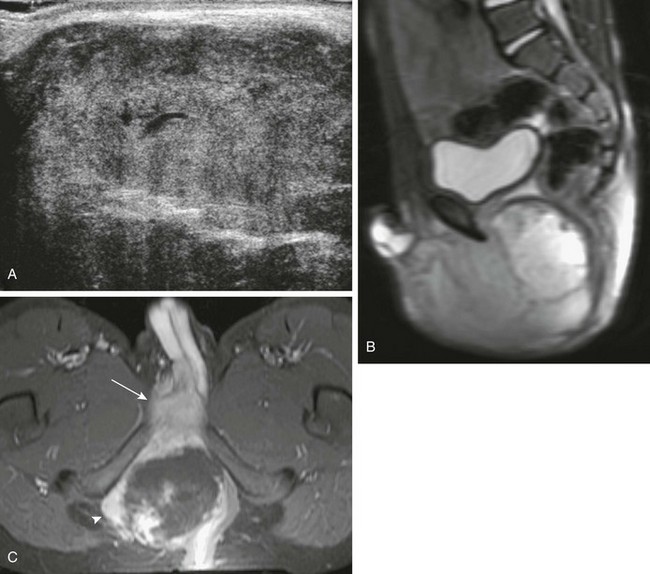

Figure 121-11 Prostatic rhabdomyosarcoma.

A, A transverse sonogram of the pelvis in a 5-year-old boy shows a large predominately isoechoic mass below the bladder base (arrow). B, A coronal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging scan shows the bladder base displaced to the left (black arrow) and the rectum displaced to the left and partially encased (white arrow). See e-Figure 121-12.

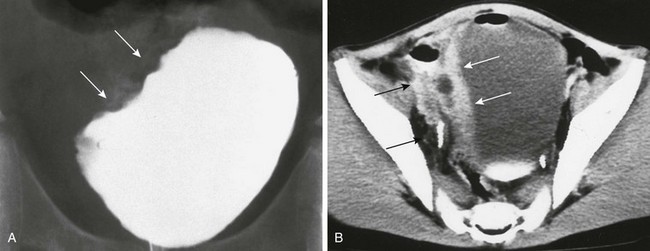

e-Figure 121-10 Rhabdomyosarcoma.

A, Cystogram from a 9-year-old boy with hematuria shows a lobular mass involving the right bladder (arrows). B, A contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows thickening and enhancement of the right bladder wall (white arrows) and extension toward the right pelvic sidewall (black arrows).

e-Figure 121-12 Prostatic rhabdomyosarcoma.

A, A longitudinal transperineal sonogram better demonstrates the large solid mass. B, A sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging scan shows a large, lobulated, bright, and heterogeneous mass extending from the bladder base to the perineum. C, An axial, T1-weighted, fat-saturated magnetic resonance imaging scan shows the mass extends through the right obturator foramen (arrowhead) and there is direct invasion of the base of the penis (arrow).

Treatment: The Children’s Oncology Group and Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study staging and clinical system for neoplasms of the genitourinary system is given in Box 121-2.18 Treatment combines surgical removal of as much of the tumor as possible, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. Tumors of the urinary bladder and prostate have an overall 5-year survival rate of approximately 70%. Tumors originating in nonbladder or prostatic sites (paratesticular, vagina, and cervix) have better 5-year survival rates, between 84% and 89%.23 Botryoid histology has the most favorable prognosis compared with all other histologies.24

Benign Neoplasms

Overview and Imaging: Hemangioma of the bladder is probably the most common benign neoplasm (0.6% of all bladder tumors). Hemangioma presents as a discrete solitary mass of variable size (<1 cm to more than 10 cm), usually projecting from the posterior or lateral walls of the bladder.25 Hematuria is the most common clinical presentation. Ultrasound will demonstrate bladder wall thickening, intramural anechoic spaces, and occasional calcification. CT and MRI may be required to fully define the extent of the lesion and for preoperative planning, since cystoscopy may only reveal a small portion of the mass.26

Nephrogenic adenoma is a rare benign papillary lesion of the bladder. In most cases. a history of upper urinary tract infection, inflammation, trauma or recent surgery (ureteral re-implantation), calculi, or catheterization is present. The bladder is the most common site in children.27 The female to male ratio in children is 3 : 1. Clinical presentation includes hematuria, frequency or urgency, and nocturia. Ultrasound demonstrates a nonspecific, echogenic papillary mass projecting from the bladder wall (Fig. 121-13).28 Most nephrogenic adenomas are less than 1 cm in size; however, they may be as large as 7 cm.29 Treatment consists of transurethral resection and fulguration. The recurrence rate in children is 80%, with peak recurrence at approximately 4 years after treatment.28,30

Posterior Urethral Valves

Overview: Posterior urethral valves (PUVs), more recently considered congenital obstructive posterior urethral membranes, are the most common cause of congenital bladder outlet obstruction.31–34 The valves are identified at the base of the verumontanum, and the obstruction leads to posterior urethral dilation and chronic bladder outlet obstruction. The degree of urethral obstruction, however, is variable.32,35–37 When detected prenatally, varying degrees of renal dysplasia result from pressure damage to the developing renal pelvis, collecting ducts, and parenchyma. If the fetus survives, up to 45% will develop renal insufficiency or end-stage renal disease requiring renal dialysis or transplantation before 5 years of age.38–41 Those children who escape antenatal detection may present in the first months or years of life with urinary tract infections, sepsis, voiding disorders, hematuria, vomiting, failure to thrive, urinary retention, hydronephrosis, ascites, and congestive heart failure. At the other end of the spectrum are patients with late presentation of PUVs. These patients have a mild form of disease, and detection may be delayed as late as adolescence. These children may present with functional voiding disorders or urinary tract infections.42,43

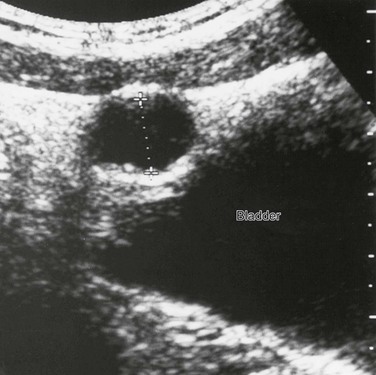

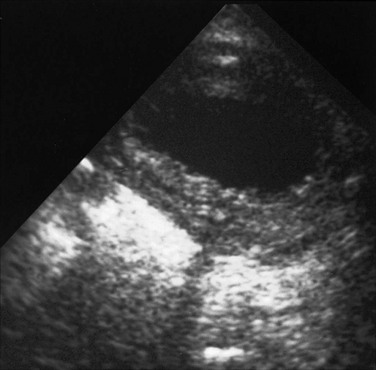

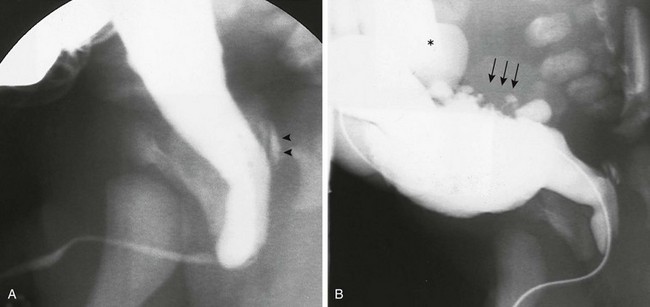

Imaging: Ultrasound shows varying degrees of hydroureteronephrosis and bladder wall thickening (e-Fig. 121-14). Dysplastic kidneys with increased echogenicity, decreased corticomedullary differentiation, and cortical cyst formation may be seen. Perinephric fluid collections (urinomas) are usually related to forniceal rupture (Fig. 121-15 and e-Fig. 121-16). When unexplained ascites is discovered in a male newborn, the diagnosis of urinary tract obstruction caused by PUVs should be strongly considered. Associated hydroureteronephrosis may not be present because the forniceal rupture and communication to the peritoneal cavity act as a “pop off” mechanism, allowing one or both kidneys to decompress. Transperineal ultrasound can show the dilated posterior urethra, especially if the child is voiding at the time of the examination (e-Fig. 121-17).44–50

Figure 121-15 Perinephric fluid collection.

A transverse prone image of a subcapsular urinoma with mass effect on the left kidney. See e-Figure 121-16.

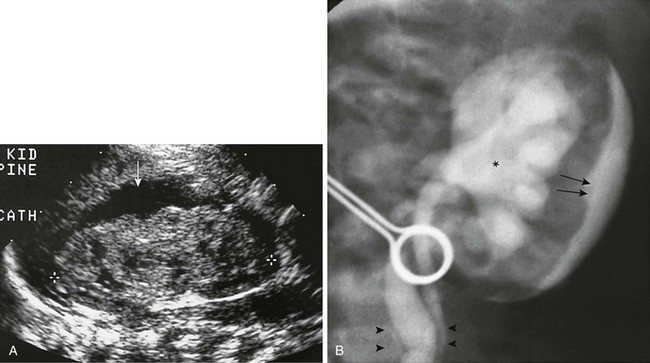

e-Figure 121-16 Perineprhic fluid collection.

A, A longitudinal ultrasound scan of a perinephric subcapsular fluid collection (arrow), likely a urinoma. No dilation of the intrarenal collecting system is present because it has decompressed into the subcapsular space. B, A voiding cystourethrogram in a neonate with posterior urethral valves shows grade IV-V vesicoureteric reflux (asterisk), intrarenal reflux, and either transparenchymal flow of contrast material into the subcapsular space or forniceal rupture with contrast material in the same location (arrows). Contrast material also tracks down along the ureter (arrowheads).

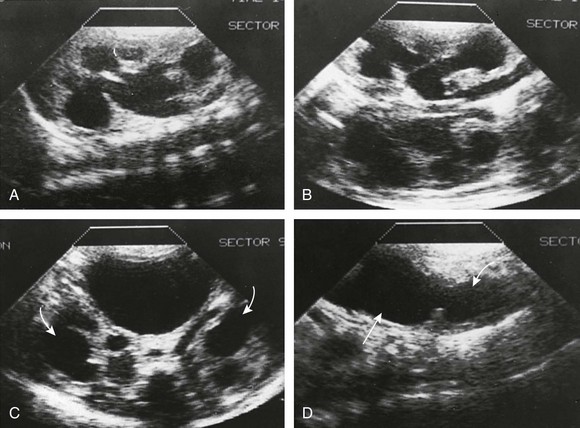

e-Figure 121-17 Posterior urethral valves in a 7-day-old male infant strongly suspected on the basis of a fetal ultrasound examination.

A and B, Longitudinal ultrasound sections of the right kidney (A) and left kidney (B) show bilateral dilation of the pelvicalyceal systems. C, Bilateral ureterectasis also is present extending down to the bladder (arrows). The bladder was very large. D, A midline longitudinal ultrasound scan of the bladder with the transducer directly caudally shows dilation of the posterior urethra (curved arrow). Straight arrow points to the bladder.

VCUG is the diagnostic study of choice for PUVs (Fig. 121-18 and e-Fig. 121-19). VCUG directly shows the PUVs and their effect on the urinary bladder; wall thickening, trabeculation with cellulae and sacculi, diverticula, and hypertrophy of the interureteric ridge (e-Fig. 121-20). Vesicoureteral reflux occurs in about one half to two thirds of male children with PUV, of whom approximately two thirds have unilateral reflux (e-Fig. 121-21) (Box 121-3).34,35,51,52

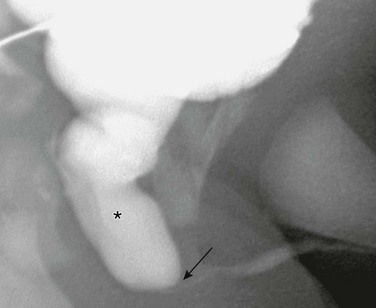

Figure 121-18 Posterior urethral valves.

Oblique image during voiding cystourethrography shows a dilated posterior urethra (asterisk) with abrupt transition at level of valves to a narrow anterior urethra (arrow). See e-Figure 121-19.

e-Figure 121-19 Posterior urethral valves.

A, A transverse ultrasound image of the bladder shows dilated posterior urethra (asterisk), representing the “keyhole” sign. B, An anterior image of the same patient demonstrates a heavily trabeculated bladder with severe bilateral vesicoureteral reflux. C, Longitudinal sonogram of the same patient demonstrates an echogenic right kidney with absent corticomedullary differentiation and hydronephrosis.

e-Figure 121-20 Posterior urethral valve on voiding cystourethrogram.

A, Steep oblique view from a voiding cystourethrogram shows posterior urethral valves. The valves are clearly at the bottom of the verumontanum, with the distal urethral lumen eccentric and posterior in position. The posterior urethra related to the obstruction is dilated, and reflux into the ejaculatory ducts is seen (arrowheads). These are the type I valves described by Young and colleagues. B, A voiding cystourethrogram of the same neonate shows a trabeculated bladder with cellulae and sacculi (arrows). Left-sided vesicoureteric reflux (asterisk) is seen. The catheter obstructs the urethral lumen.

e-Figure 121-21 Infant with posterior urethral valves.

A, A cystogram shows severe left-sided reflux. B, An excretory urogram shows poor renal function and severe upper tract dilation bilaterally. Rim sign on the right represents a dense collection of contrast material in tubules around the dilated calyces.

Treatment: Transurethral resection or fulguration of the obstructing valvular structures is the recommended treatment for PUVs. Residual valve tissue with obstruction is not uncommon, and stricture formation at the site of previous urethral valves or in the membranous urethra as a complication of surgery may occur. Urethroscopy is usually more reliable than the urethrogram in the diagnosis of these lesions.53–63

Posterior Urethral Polyps

Overview: Urethral polyps typically arises from the posterior urethra and consist of an elongated, freely movable mass on a long stalk originating from the region of the verumontanum (Box 121-4).64 The lesion is typically diagnosed in the first decade of life at a mean age of 8 to 10 years. The classic symptoms are those of intermittent urethral obstruction with straining on voiding, abnormal voiding pattern, and urinary retention.65,66 Hematuria (30%–60%) and urinary tract infections may also be observed.64–67

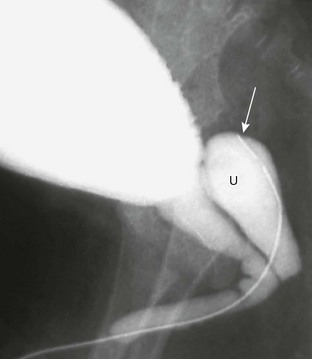

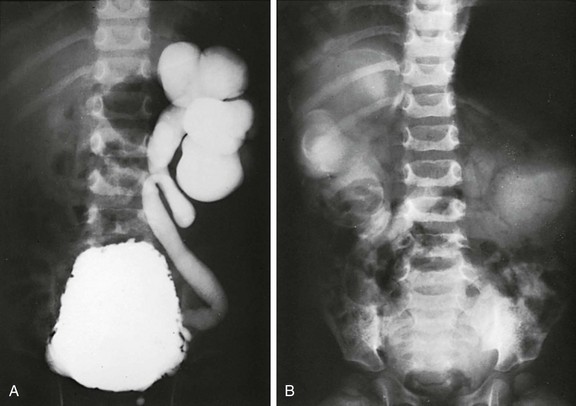

Imaging: VCUG remains the imaging gold standard. Before voiding, the tip of the polyp is frequently located at the level of the bladder neck, causing a small rounded filling (Fig. 121-22 and e-Fig. 121-23). In the voiding phase, the polyp moves downward into the distal posterior urethra and occasionally into the bulbar urethra. At the end of voiding, the polyp is displaced backward to the level of the bladder outlet by the contraction of the external urethral sphincter. Ultrasound may demonstrate a mobile pedunculated mass at the bladder base and indirect signs of bladder outlet obstruction (hydronephrosis and large bladder with or without bladder wall hypertrophy.65–69

Figure 121-22 Urethral polyp.

Oblique image during voiding cystourethrography shows a lobular filling defect in the posterior urethra representing a polyp on a stalk (arrows). See Figure 121-22.

Prostatic Utricle

Overview: The prostatic utricle is an epithelium-lined diverticulum of the prostatic urethra, the remnant of the fused caudal ends of the müllerian ducts. It is located in the verumontanum between the openings of the two ejaculatory ducts. When secretion or resistance to müllerian inhibitory factor is deficient, regression of the müllerian ducts is incomplete, resulting in an enlarged prostatic utricle and varying degrees of hypospadias (secondary to incomplete androgen-mediated closure of the urogenital sinus). The increasing severity of the hypospadias correlates with the increasing size of the utricle.70 Poor emptying leads to urine retention and stasis. Clinically, this presents as lower urinary tract voiding symptoms, urinary retention, epididymitis, urethral discharge caused by urinary infection or stone formation, or postvoid dribbling caused by delayed utricle drainage.71

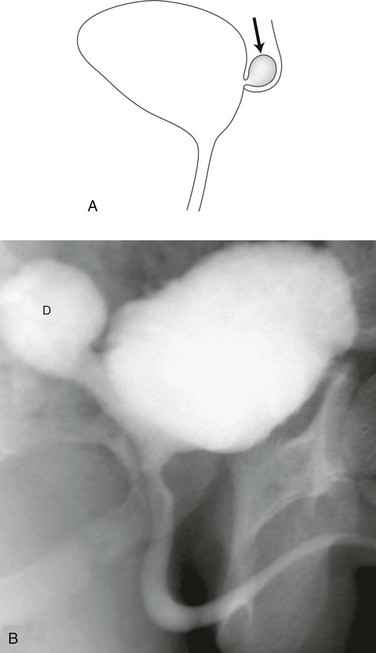

Imaging: VCUG and retrograde urethrography (RUG) define the utricular size and its origin from the prostatic urethra, and associated hypospadias (Fig. 121-24). Direct catheterization of the bladder during VCUG may be difficult secondary to preferential passage into the utricle (e-Fig. 121-25). Transabdominal ultrasound may demonstrate a retrovesical cystic mass, with or without internal debris, tapering to the expected location of the posterior urethra. CT and MRI imaging will demonstrate a thin-walled cystic lesion originating from the prostatic urethral region, with or without associated mass effect on the bladder and ureters.72,73

Figure 121-24 Utricle.

A, A longitudinal ultrasound image of the bladder in patient with hypospadias shows a blind-ending anechoic tubular structure (asterisk) posterior to the bladder. B, Corresponding oblique view from a voiding cystourethrogram shows a large utricle (arrow) extending posterior to the bladder.

Abnormalities of Cowper’s Glands

Overview: Bulbourethral (Cowper’s) glands are two pea-sized bodies on either side of the membranous urethra between the two layers of the urogenital diaphragm (Fig. 121-26). Their ducts are 2 to 3 cm in length and are directed forward through the bulb of the corpus spongiosum to end in the ventral aspect of the bulbar urethra. These accessory sexual organs secrete a clear mucous substance that acts as a lubricant for spermatozoa.75–78

Figure 121-26 Various Configurations of Cowper’s ducts and Cowper’s glands on urethrography.

A, Filling of the duct up to the gland. B, Opening of the duct is obliterated, causing a small mass on the floor of the bulbar urethra. C and D, Diverticula originating from the floor of the bulbar urethra; the duct is not usually opacified in these cases.

Imaging: Both the ducts and glands may opacify during VCUG when the distal orifice is patulous. A contrast medium–filled tubular structure is seen paralleling the undersurface of the bulbous urethra (e-Fig. 121-27). This finding, as a rule, is of no clinical significance. When the ductal orifice becomes stenotic, a dilated Cowper’s gland (syringocele) and duct are formed. The diagnosis can be made at VCUG by demonstrating a smooth extrinsic mass effect along the ventral surface of the bulbous urethra (Fig. 121-28).75,76,79,80

Figure 121-28 Cowper’s duct cyst (syringocele).

An oblique image from a retrograde urethrogram shows a lobular filling defect (arrow) along the ventral surface of the bulbous urethra.

Anterior Urethral Diverticula, Anterior Urethral Valve, and Megalourethra

Overview: These uncommon anomalies of the male urethra are considered together because of common features and transitional forms suggesting a spectrum of related deformities.83 The difference resides in their relationship to the corpus spongiosum. The urethral arch accompanying valves may take on a “pseudodiverticular” appearance but remains bordered by the corpus spongiosum. In contrast, a true diverticulum develops outside the corpus spongiosum, which is completely absent from the margin of the diverticular pouch. The urethral diverticulum may be more anatomically linked to the megalourethra, in which the corpus spongiosum (scaphoid megalourethra), corpora cavernosa (fusiform megalourethra), or both are deficient.84

Anterior Urethral Diverticulum

Overview: Anterior urethral diverticulum is a saccular outpouching of the ventral aspect of the anterior urethra into the corpus spongiosum, usually near the penoscrotal junction.83,85,86 The corpora cavernosa are intact. During voiding, urine distends the diverticulum and displaces the anterior lip of the diverticulum forward and against the dorsal wall of the urethra, obstructing the flow of urine. A tense bulge on the ventral aspect of the penis at the level of the diverticulum may be observed during voiding. The clinical symptoms depend on the degree of obstruction and include urinary retention, poor urinary stream, dribbling of urine, enuresis, and urinary tract infection.87,88

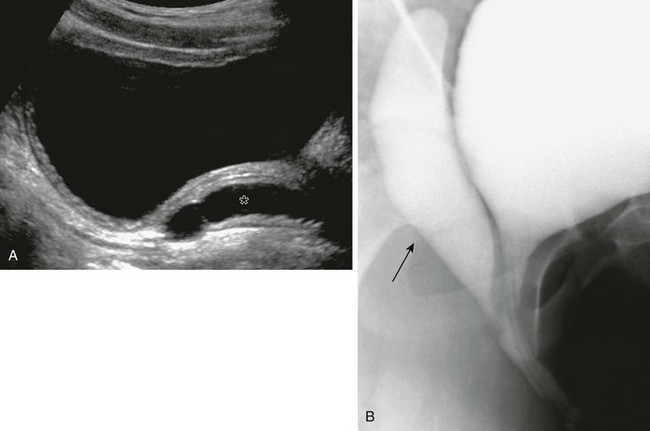

Imaging: VCUG is the diagnostic tool of choice. Imaging of the urethra in an anterior oblique position will demonstrate a wide-mouthed, focal outpouching of the ventral urethra of variable size (up to 3 to 5 cm in diameter).84 The urethra proximal to the diverticulum is dilated, with a sharp demarcation with the unobstructed distal urethra (Fig. 121-29). The proximal margin of the urethral diverticulum forms an acute angle with the floor of the ventral urethra.83 The lesion is not clearly visualized on a retrograde urethrogram.89

Treatment: Transurethral resection of the distal margin of the diverticulum with a hooked, single-wire or electrocautery knife is often successful. Open primary reconstruction, with diverticulectomy and urethroplasty, provides a more homogeneous caliber to the urethra. In the presence of infection, marsupialization of the diverticulum and urinary diversion followed by secondary repair is recommended.83,85,87

Anterior Urethral Valve

Overview: Anterior urethral valves (AUVs) are congenital mucosal folds located distal to the membranous urethra.90 The valvular tissue is directed backward and is anchored laterally such that it is raised up against the dorsal aspect of the urethra during voiding, obstructing the flow of urine. It differs from a urethral diverticulum in that it lacks a posterior lip and usually causes a lesser degree of localized swelling of the ventral aspect of the penis during micturition.84 No abnormalities of the corpus spongiosum or corpora cavernosa are present. The clinical manifestations and complications are the same as those described for anterior urethral diverticula but are often milder.

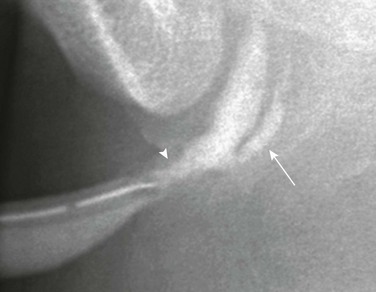

Imaging: VCUG is the diagnostic tool of choice. The urethra has a more fusiform dilation proximal to the valve and is narrow distally. A thickened band of valvular tissue is seen at the transition, assuming an iris-like, semi-lunar, or cusp-like configuration (Fig. 121-30 and e-Fig. 121-31).87,91 AUVs may produce a proximal dilation of the urethra that mimics a diverticulum. However, in “pseudodiverticula” formation caused by AUVs, the proximal end of the urethral dilation forms an obtuse angle with the ventral floor of the urethra, unlike the acute angle seen in a true urethral diverticulum.83,91

Figure 121-30 Anterior urethral valve.

An oblique image during voiding cystourethrography shows a focal saccular dilation of the distal anterior urethra. Distally, an acute angle is formed at the junction with the narrowed urethra (arrow). Proximally, an obtuse angle is present (arrowhead). (From Bates DG, Coley BD. Ultrasound diagnosis of the anterior urethral valve. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:634-636.) See e-Figure 121-31.

e-Figure 121-31 Anterior urethral valve.

A longitudinal ultrasound image of the urethra during voiding shows thin echogenic valve traversing the urethra (arrow). Proximal to the valve, urethral dilation is seen (asterisk). (From Bates DG, Coley BD. Ultrasound diagnosis of the anterior urethral valve. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:634-636.)

Scaphoid and Fusiform Megalourethra

Overview: The scaphoid megalourethra is much more common than the fusiform type. It consists of a saccular dilatation of the penile urethra, caused by the absence or underdevelopment of the corpus spongiosum. Ventrally, the penis is soft and baggy with redundant skin. During voiding, the affected part of the urethra balloons markedly, causing a large, smooth bulge in the ventral surface of the penis. The penis and pendulous urethra assume a scaphoid (boat-shaped) configuration. The patient voids with a poor stream.35,92

Fusiform megalourethra, less common and more severe than the scaphoid form, is characterized by a diffuse ectasia of the penile urethra secondary to the absence or partial deficiency of the corpus spongiosum and corpora cavernosa. The penis is large, misshapen, and flabby, with redundant and wrinkled skin.35 During voiding, the urethra and penis become markedly distended. The patient voids with a poor urinary stream. Clinical symptoms and the prognosis vary with the severity of the associated anomalies (e.g., “prune belly syndrome”).

Imaging: On VCUG or RUG, the dilated ventral segment of the scaphoid urethra dilates and blends gradually with a normal urethra distally and proximally. The fusiform megalourethra is markedly dilated, tapering both distally and proximally into a relatively normal urethra (Fig. 121-32). The proximal urethra may be dilated. Sometimes, the anomaly affects only a small portion of the urethra (e-Fig. 121-33).93,94

Figure 121-32 Megalourethra.

An oblique image from a retrograde urethrogram shows fusiform dilation of the penile urethra.

Urethral Duplication

Overview: A single unifying theory does not exist to explain all the various forms of duplication, and more than one classification scheme exists in the literature. These developmental anomalies are characterized by the presence of a complete or partial accessory urethral channel arising from the bladder to the distal urethra. Incomplete duplications arise from the penile surface or from the urethral channel but end blindly in the periurethral tissue.95–98 Sagittal plane duplication is most common with a ventral and dorsal urethra (one urethra atop the other). It is important to remember that in almost all cases, the ventral urethra is the functioning channel and contains the urethral sphincter and verumontanum. According to the location of the accessory urethral opening on the dorsal or ventral aspect of the penis, urethral duplications are divided into epispadic (the most common type) and hypospadic types, respectively.99–101

In the epispadic type, an incomplete accessory channel has a dorsal opening in the penis and ends blindly. The complete or partial forms originate from the bladder or proximal urethra and course through the dorsal aspect of the penis to end in an epispadic position anywhere between the glans and the root of the penis, or rarely they originate from a minute cavity (nonfunctional sagittal plane duplicated bladder) located behind the pubic symphysis and in front of the normal bladder. The ventral urethra is normally positioned and ends in the glandular meatus (although rarely is hypospadic).96,98–101

In the hypospadic type, an incomplete accessory channel has a ventral opening in the penis and ends blindly or originates from the normal proximal urethra and ends blindly in the periurethral tissue, similar in appearance to a urethral diverticulum or Cowper’s duct. Complete or partial duplications arise from the bladder or proximal urethra and course through the ventral aspect of the penis to end in a hypospadic position along the shaft.96–98,102

An important form of urethral duplication of the hypospadic type is referred to as Y-type duplication. The ventral urethra originates from the midprostatic urethra and terminates in the anal canal or in the perineum along the anterior anal margin. Urine flows preferentially through this ventral channel and is considered the normal urethra as it traverses the sphincter mechanism. A normally positioned dorsal urethra is usually stenotic or partially atretic.103–106

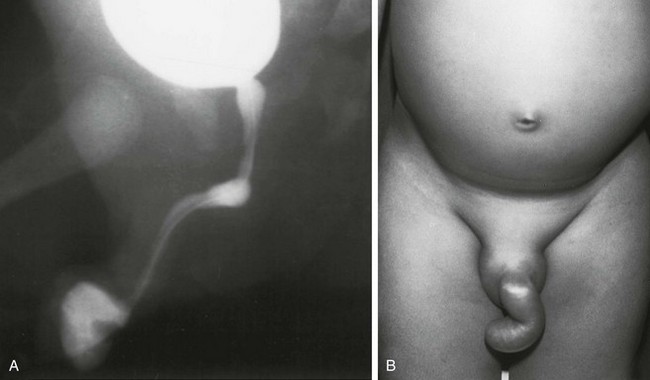

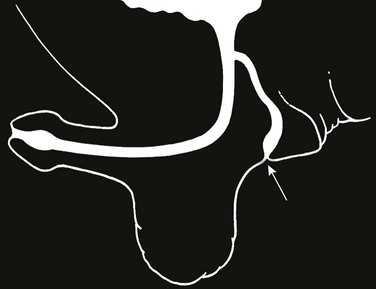

The congenital urethroperineal fistula has a similar location to the Y-type duplication, but is a distinctly different developmental anomaly (Fig. 121-34 and e-Fig. 121-35). The normally positioned dorsal channel is the functioning urethra in this case, and micturition is normal. Clinically, only a few drops of urine are present at the perineal opening.107–109

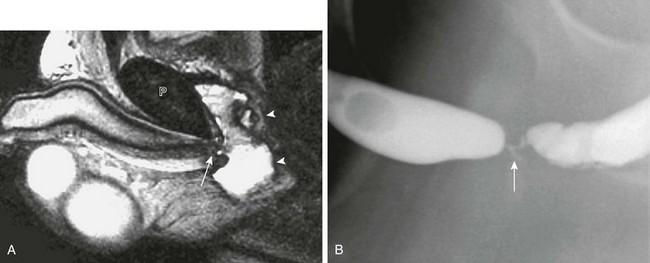

Figure 121-34 Urethroperineal fistula.

Schematic diagram showing the perineal fistula (arrow) originating from the normal dorsal urethra. This is the exception to the rule that the ventral urethra is the normal urethra in duplications. (From Bates DG, Lebowitz RL. Congenital urethroperineal fistula. Radiology. 1995;194:501-504.) See e-Figure 121-35.

e-Figure 121-35 Urethroperineal fistula.

A, An oblique image from a voiding cystourethrogram shows a congenital perineal fistula (arrowheads) originating from the prostatic urethra as is represented in the schematic diagram. B, A photograph of another patient, showing a probe within the perineal urethra. (From Bates DG, Lebowitz RL. Congenital urethroperineal fistula. Radiology. 1995;194:501-504.)

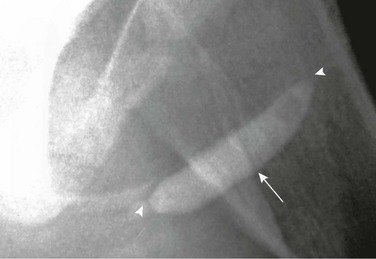

Imaging: Appropriate evaluation or urethral duplication includes anatomic evaluation of all channels, recognition of the functional urethra and identification of associated anomalies.95,96,98 VCUG is adequate if both urethral channels can be clearly identified (Fig. 121-36 and e-Fig. 121-37). RUG may be necessary for hypoplastic channels not visualized on VCUG. Cystoscopy may be performed to confirm the radiographic findings and to precisely identify which urethra contains the sphincteric mechanism and normal verumontanum.97,102

Figure 121-36 Urethral duplications.

An oblique image during voiding cystourethrography shows triplication of the urethra (arrowheads) originating from the prostatic urethra. See e-Figure 121-37.

Urethral Strictures

Overview: Iatrogenic strictures, which account for about two thirds of the cases, are located predominantly near the penoscrotal junction, an area that is particularly vulnerable to internal trauma. Pelvic fractures, penetrating injuries, direct blows to the perineum, and straddle injuries are the most common forms of external trauma. Urethral infections are uncommon causes of urethral strictures in children as opposed to young adults, in whom urethral strictures are often due to Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection.111–115 Urethral strictures of unknown cause in symptomatic boys are not rare. They may be the result of unrecognized external trauma or urethritis, Cowper’s duct infection, or rupture of a Cowper’s duct cyst, or they may be secondary to incomplete dissolution of the urogenital membrane at the junction of the cloaca and genital groove (Cobb’s collar).116,117 The clinical manifestations of urethral strictures include poor urinary stream, straining to void, urinary retention, painful urination, hematuria, urinary infections, and recurrent epididymitis.

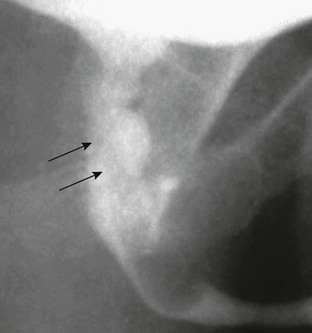

Imaging: The diagnosis is readily established by VCUG when the bladder can be catheterized. Compression of the distal penis during voiding (choke urethrogram) or RUG results in distention of the normal urethra and a better delineation of the true extent of the stricture. The membranous urethra is the area most often injured, owing to its fixation by the urogenital diaphragm. Strictures from straddle injuries are usually located in the bulbar urethra (Fig. 121-38 and e-Fig. 121-39). Congenital strictures are located most often in the bulbar urethra and are usually very short and diaphragm-like (Fig. 121-40). An alternative to fluoroscopic evaluation is ultrasound of the urethra, which provides information about the urethra as well as periurethral tissues. In the interpretation of the urethrogram, it is important to keep in mind those normal areas of narrowing at the level of the urogenital diaphragm or narrowing caused by spasm of the bulbocavernosus or external sphincter muscles that may simulate a stricture.111,115,118–121

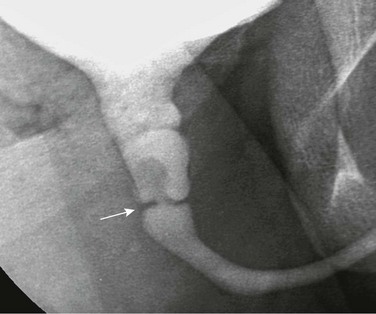

Figure 121-38 Straddle injury.

A retrograde urethrogram shows bulbar urethral disruption (arrow) and contrast extravasation. See e-Figure 121-39.

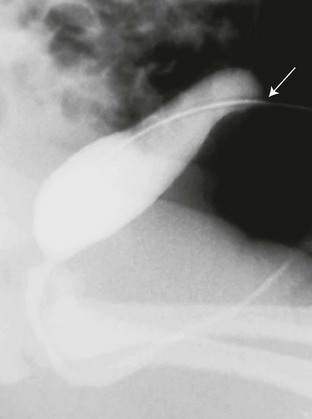

Figure 121-40 Congenital urethral diaphragm.

An oblique image during voiding cystourethrography shows a linear filling defect in the posterior urethra at the base of the verumontanum (arrow). Mild posterior urethra dilation is present.

e-Figure 121-39 Straddle injury.

A, A sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging scan in the same patient as in Figure 121-38 shows urethral disruption (arrow) directly beneath the pubis (P). The urethral fragments are separated by an intervening hematoma (arrowheads). B, A follow-up retrograde urethrogram after repair shows high-grade urethral stricture (arrow).

Treatment: Three major forms of treatment exist for urethral stricture: (1) urethral dilation, which is the oldest and simplest treatment; (2) open reconstruction with urethroplasty, which is regarded as the gold standard; and (3) internal urethrotomy by incising or ablating the stricture transurethrally.122,123

Agrons, GA, Wagner, BJ, Lonergan, GJ, et al. From the archives of the AFIP. Genitourinary rhabdomyosarcoma in children: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1997;17(4):919–937.

Berrocal, T, Lopez-Pereira, P, Arjonilla, A, et al. Anomalies of the distal ureter, bladder, and urethra in children: embryologic, radiologic, and pathologic features. Radiographics. 2002;22:1139–1164.

Evangelidis, A, Castle, EP, Ostlie, DJ, et al. Surgical management of primary bladder diverticula in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:701–703.

Jones, EA, Freedman, AL, Ehrlich, RM. Megalourethra and urethral diverticula. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29:341–348.

Kawashima, A, Sandler, CM, Wasserman, NF, et al. Imaging of urethral disease: a pictorial review. Radiographics. 2004;24(suppl 1):S195–S216.

Koff, SA, Mutabagani, KH, Jayanthi, VR. The valve bladder syndrome: pathophysiology and treatment with nocturnal bladder emptying. J Urol. 2002;167(1):291–297.

Krishnan, A, deSouza, A, Konijeti, R, et al. The anatomy and embryology of posterior urethral valves. J Urol. 2006;175:1214–1220.

Levin, TL, Han, B, Little, BP. Congenital anomalies of the male urethra. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37(9):851–862. quiz 945

Little, DC, Shah, SR, St Peter, SD, et al. Urachal anomalies in children: the vanishing relevance of the preoperative voiding cystourethrogram. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1874–1876.

Pavlica, P, Barozzi, L, Menchi, I. Imaging of the male urethra. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:1583–1596.

Poggiani, C, Teani, M, Auriemma, A, et al. Sonographic detection of rhabdomyosarcoma of the urinary bladder. Eur J Ultrasound. 2001;13:35.

Schneider, G, Ahlhelm, F, Altmeyer, K, et al. Rare pseudotumors of the urinary bladder in childhood. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:1024–1029.

Troiano, RN, McCarthy, SM. Müllerian duct anomalies: imaging and clinical issues. Radiology. 2004;233:19–34.

Wu, HY, Snyder, HM, 3rd., Womer, RB. Genitourinary rhabdomyosarcoma: which treatment, how much, and when? J Pediatr Urol. 2009;5(6):501–506.

Yapo, BR, Gerges, B, Holland, AJ. Investigation and management of suspected urachal anomalies in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24(5):589–592.

References

1. Yapo, BR, Gerges, B, Holland, AJ. Investigation and management of suspected urachal anomalies in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24(5):589–592.

2. Galati, V, Donovan, B, Ramji, F, et al. Management of urachal remnants in early childhood. J Urol. 2008;180(suppl 4):1824–1826. [discussion 1827].

3. Yu, JS, Kim, KW, Lee, HJ, et al. Urachal remnant diseases: spectrum of CT and US findings. Radiographics. 2001;21(2):451–461.

4. Widni, EE, Hollwarth, ME, Haxhija, EQ. The impact of preoperative ultrasound on correct diagnosis of urachal remnants in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(7):1433–1437.

5. Ozbek, SS, Pourbagher, MA, Pourbagher, A. Urachal remnants in asymptomatic children: gray-scale and color Doppler sonographic findings. J Clin Ultrasound. 2001;29(4):218–222.

6. Kurtz, M, Masiakos, PT. Laparoscopic resection of a urachal remnant. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(9):1753–1754.

7. Boechat, MI, Lebowitz, RL. Diverticula of the bladder in children. Pediatr Radiol. 1978;7(1):22–28.

8. Stein, RJ, Matoka, DJ, Noh, PH, et al. Spontaneous perforation of congenital bladder diverticulum. Urology. 2005;66(4):881.

9. Ryoo, JW, Cho, JM. Multiple bladder diverticula in Menkes disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38(5):595.

10. Zia-Ul-Miraj, M. Congenital bladder diverticulum: a rare cause of bladder outlet obstruction in children. J Urol. 1999;162(6):2112–2113.

11. Hernanz-Schulman, M, Lebowitz, RL. The elusiveness and importance of bladder diverticula in children. Pediatr Radiol. 1985;15(6):399–402.

12. Hutch, JA. Saccule formation at the ureterovesical junction in smooth walled bladders. J Urol. 1961;86:390–399.

13. Badawy, H, Eid, A, Hassouna, M, et al. Pneumovesicoscopic diverticulectomy in children and adolescents: is open surgery still indicated? J Pediatr Urol. 2008;4(2):146–149.

14. Singal, AK, Chandrasekharam, VV. Lower urinary tract obstruction secondary to congenital bladder diverticula in infants. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25(12):1117–1121.

15. Afshar, K, Malek, R, Bakhshi, M, et al. Should the presence of congenital para-ureteral diverticulum affect the management of vesicoureteral reflux? J Urol. 2005;174(4 Pt 2):1590–1593.

16. Shukla, AR, Bellah, RA, Canning, DA, et al. Giant bladder diverticula causing bladder outlet obstruction in children. J Urol. 2004;172(5 Pt 1):1977–1979.

17. Wu, HY, Snyder, HM, 3rd. Pediatric urologic oncology: bladder, prostate, testis. Urol Clin North Am. 2004;31(3):619–627.

18. Wu, HY, Snyder, HM, 3rd., Womer, RB. Genitourinary rhabdomyosarcoma: which treatment, how much, and when? J Pediatr Urol. 2009;5(6):501–506.

19. Agrons, GA, Wagner, BJ, Lonergan, GJ, et al. From the archives of the AFIP. Genitourinary rhabdomyosarcoma in children: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1997;17(4):919–937.

20. Parwani, AV, Rosenthal, DL, Epstein, JI, et al. Pathologic quiz case: a 3-year-old girl with dysuria and urinary incontinence. Primary embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the urinary bladder. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128(3):357–358.

21. Nigro, KG, MacLennan, GT. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the bladder and prostate. J Urol. 2005;173(4):1365.

22. Poggiani, C, Teani, M, Auriemma, A, et al. Sonographic detection of rhabdomyosarcoma of the urinary bladder. Eur J Ultrasound. 2001;13(1):35–39.

23. Leuschner, I, Harms, D, Mattke, A, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the urinary bladder and vagina: a clinicopathologic study with emphasis on recurrent disease: a report from the Kiel Pediatric Tumor Registry and the German CWS Study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(7):856–864.

24. Rodeberg, DA, Anderson, JR, Arndt, CA, et al. Comparison of outcomes based on treatment algorithms for rhabdomyosarcoma of the bladder/prostate: combined results from the Children’s Oncology Group, German Cooperative Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study, Italian Cooperative Group, and International Society of Pediatric Oncology Malignant Mesenchymal Tumors Committee. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(5):1232–1239.

25. Ashley, RA, Figueroa, TE. Gross hematuria in a 3-year-old girl caused by a large isolated bladder hemangioma. Urology. 2010;76(4):952–954.

26. Jahn, H, Nissen, HM. Haemangioma of the urinary tract: review of the literature. Br J Urol. 1991;68:113–117.

27. Campobasso, P, Fasoli, L, Dante, S. Sodium hyaluronate in treatment of diffuse nephrogenic adenoma of the bladder in a child. J Pediatr Urol. 2007;3(2):156–158.

28. Rossi, E, Pavanello, P, Marzola, A, et al. Eosinophilic cystitis and nephrogenic adenoma of the bladder: a rare association of 2 unusual findings in childhood. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46(4):e31–e34.

29. Kunju, LP. Nephrogenic adenoma: report of a case and review of morphologic mimics. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134(10):1455–1459.

30. Vemulakonda, VM, Kopp, RP, Sorensen, MD, et al. Recurrent nephrogenic adenoma in a 10-year-old boy with prune belly syndrome: a case presentation. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24(5):605–607.

31. Imaji, R, Dewan, PA. Congenital posterior urethral obstruction: re-do fulguration. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002;18(5-6):444–446.

32. Imaji, R, Moon, DA, Dewan, PA. Congenital posterior urethral membrane: variable morphological expression. J Urol. 2001;165(4):1240–1242. [discussion 1242-1243].

33. Dewan, PA, Zappala, SM, Ransley, PG, et al. Endoscopic reappraisal of the morphology of congenital obstruction of the posterior urethra. Br J Urol. 1992;70:439–444.

34. Young, HH, Frontz, WA, Baldwin, JC, Congenital obstruction of the posterior urethra. J Urol 1919;3:289–365. J Urol 167:265-267; discussion 268, 2002

35. Berrocal, T, Lopez-Pereira, P, Arjonilla, A, et al. Anomalies of the distal ureter, bladder, and urethra in children: embryologic, radiologic, and pathologic features. Radiographics. 2002;22:1139–1164.

36. Krishnan, A, deSouza, A, Konijeti, R, et al. The anatomy and embryology of posterior urethral valves. J Urol. 2006;175:1214–1220.

37. Cohen, HL, Kravets, F, Zucconi, W, et al. Congenital abnormalities of the genitourinary system. Semin Roentgenol. 2004;39:282–303.

38. El-Ghoneimi, A, Desgrippes, A, Luton, D, et al. Outcome of posterior urethral valves: to what extent is it improved by prenatal diagnosis? J Urol. 1999;162:849–853.

39. Reinberg, Y, de Castano, I, Gonzalez, R. Prognosis for patients with prenatally diagnosed posterior urethral valves. J Urol. 1992;148:125–126.

40. Ylinen, E, Ala-Houhala, M, Wikstrom, S. Prognostic factors of posterior urethral valves and the role of antenatal detection. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:874–879.

41. Eckoldt, F, Heling, KS, Woderich, R, et al. Posterior urethral valves: prenatal diagnostic signs and outcome. Urol Int. 2004;73:296–301.

42. Schober, JM, Dulabon, LM, Woodhouse, CR. Outcome of valve ablation in late-presenting posterior urethral valves. BJU Int. 2004;94:616–619.

43. Parkhouse, HF, Woodhouse, CR. Long-term status of patients with posterior urethral valves. Urol Clin North Am. 1990;17:373–378.

44. Cohen, HL, Susman, M, Haller, JO, et al. Posterior urethral valve: transperineal US for imaging and diagnosis in male infants. Radiology. 1994;192:261–264.

45. Cohen, HL, Zinn, HL, Patel, A, et al. Prenatal sonographic diagnosis of posterior urethral valves: identification of valves and thickening of the posterior urethral wall. J Clin Ultrasound. 1998;26:366–370.

46. Feinstein, KA, Fernbach, SK. Septated urinomas in the neonate. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:997–1000.

47. Chen, C, Shih, SL, Liu, FF, et al. In utero urinary bladder perforation, urinary ascites, and bilateral contained urinomas secondary to posterior urethral valves: clinical and imaging findings. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27:3–5.

48. Mercado-Deane, MG, Beeson, JE, John, SD. US of renal insufficiency in neonates. Radiographics. 2002;22:1429–1438.

49. Kaefer, M, Keating, MA, Adams, MC, et al. Posterior urethral valves, pressure pop-offs and bladder function. J Urol. 1995;154:708–711.

50. Sahdev, S, Jhaveri, RC, Vohra, K, et al. Congenital bladder perforation and urinary ascites caused by posterior urethral valves: a case report. J Perinatol. 1997;17:164–165.

51. Imaji, R, Dewan, PA. The clinical and radiological findings in boys with endoscopically severe congenital posterior urethral obstruction. BJU Int. 2001;88(3):263–267.

52. Ditchfield, MR, Grattan-Smith, JD, de Campo, JF, et al. Voiding cystourethrography in boys: does the presence of the catheter obscure the diagnosis of posterior urethral valves? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:1233–1235.

53. Holmes, N, Harrison, MR, Baskin, LS. Fetal surgery for posterior urethral valves: long-term postnatal outcomes. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E7.

54. Holmdahl, G, Sillen, U, Hellstrom, AL, et al. Does treatment with clean intermittent catheterization in boys with posterior urethral valves affect bladder and renal function? J Urol. 2003;170:1681–1685. [discussion 1685].

55. Pereira, P, Martinez Urrutia, MJ, Jaureguizar, E. Initial and long-term management of posterior urethral valves. World J Urol. 2004;22:418–424.

56. Chertin, B, Cozzi, D, Puri, P. Long-term results of primary avulsion of posterior urethral valves using a Fogarty balloon catheter. J Urol. 2002;168(4 Pt 2):1841–1843. [discussion 1843].

57. Stuhldreier, G, Schweizer, P, Hacker, HW, et al. Laser resection of posterior urethral valves. Pediatr Surg Int. 2001;17(1):16–20.

58. Mitchell, ME, Close, CE. Early primary valve ablation for posterior urethral valves. Semin Pediatr Surg. 1996;5(1):66–71.

59. Nijman, RJ, Scholtmeijer, RJ. Complications of transurethral electro-incision of posterior urethral valves. Br J Urol. 1991;67(3):324–326.

60. Youssif, M, Dawood, W, Shabaan, S, et al. Early valve ablation can decrease the incidence of bladder dysfunction in boys with posterior urethral valves. J Urol. 2009;182(suppl 4):1765–1768.

61. Gupta, SD, Khatun, AA, Islam, AI, et al. Outcome of endoscopic fulguration of posterior urethral valves in children. Mymensingh Med J. 2009;18(2):239–244.

62. Gupta, RK, Shah, HS, Jadhav, V, et al. Urethral ratio on voiding cystourethrogram: a comparative method to assess success of posterior urethral valve ablation. J Pediatr Urol. 2010;6(1):32–36.

63. Barber, T, Al-Omar, O, McLorie, GA. Cold knife valvulotomy for posterior urethral valves using novel optical urethrotome. Urology. 2009;73(5):1012–1015.

64. Demircan, M, Ceran, C, Karaman, A, et al. Urethral polyps in children: a review of the literature and report of two cases. Int J Urol. 2006;13(6):841–843.

65. Beluffi, G, Berton, F, Gola, G, et al. Urethral polyp in a 1-month-old child. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35(7):691–693.

66. Jain, P, Shah, H, Parelkar, SV, et al. Posterior urethral polyps and review of literature. Indian J Urol. 2007;23(2):206–207.

67. Ben-Meir, D, Yin, M, Chow, CW, et al. Urethral polyps in prepubertal girls. J Urol. 2005;174(4 Pt 1):1443–1444.

68. Williams, TR, Wagner, BJ, Corse, WR, et al. Fibroepithelial polyps of the urinary tract. Abdom Imaging. 2002;27(2):217–221.

69. Natsheh, A, Prat, O, Shenfeld, OZ, et al. Fibroepithelial polyp of the bladder neck in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24(5):613–615.

70. Yeung, CK, Sihoe, JD, Tam, YH, et al. Laparoscopic excision of prostatic utricles in children. BJU Int. 2001;87(6):505–508.

71. Krsti , ZD, Smoljani

, ZD, Smoljani , Z, Mi

, Z, Mi ovi

ovi , Z, et al. Surgical treatment of the Müllerian duct remnants. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36(6):870–876.

, Z, et al. Surgical treatment of the Müllerian duct remnants. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36(6):870–876.

72. Li, CC, Ko, SF, Ng, SH, et al. Symptomatic giant Müllerian duct cyst in an infant: radiographic and CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29(4):525–527.

73. Kojima, Y, Hayashi, Y, Maruyama, T, et al. Comparison between ultrasonography and retrograde urethrography for detection of prostatic utricle associated with hypospadias. Urology. 2001;57(6):1151–1155.

74. Desautel, MG, Stock, J, Hanna, MK. Müllerian duct remnants: surgical management and fertility issues. J Urol. 1999;162(3 Pt 2):1008–1013. [discussion 1014].

75. Colodny, AH, Lebowitz, RL. Lesions of the Cowper’s ducts and glands in infants and children. Urology. 1978;11:321.

76. Chughtai, B, Sawas, A, O’Malley, RL, et al. A neglected gland: a review of Cowper’s gland. Int J Androl. 2005;28(2):74–77.

77. Campobasso, P, Schieven, E, Fernandes, EC. Cowper’s syringocele: an analysis of 15 consecutive cases. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75(1):71–73.

78. Bevers, RF, Abbekerk, EM, Boon, TA. Cowper’s syringocele: symptoms, classification and treatment of an unappreciated problem. J Urol. 2000;163(3):782–784.

79. Kickuth, R, Laufer, U, Pannek, J, et al. Cowper’s syringocele: diagnosis based on MRI findings. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32(1):56–58.

80. Beluffi, G, Fiori, P, Pietrobono, L, et al. Cowper’s glands and ducts: radiological findings in children. Radiol Med. 2006;111(6):855–862.

81. Santin, BJ, Pewitt, EB. Cowper’s duct ligation for treatment of dysuria associated with Cowper’s syringocele treated previously with transurethral unroofing. Urology. 2009;73(3):681.e11–681.e13.

82. Melquist, J, Sharma, V, Sciullo, D, McCaffrey, H, Khan, SA. Current diagnosis and management of syringocele: a review. Int Braz J Urol. 2010;36(1):3–9.

83. Gupta, DK, Srinivas, M. Congenital anterior urethral diverticulum in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2000;16:565–568.

84. Paulhac, P, Fourcade, L, Lesaux, N, et al. Anterior urethral valves and diverticula. BJU Int. 2003;92(5):506–509.

85. Kajbafzadeh, A. Congenital urethral anomalies in boys. Part II. Urol J. 2005;2(3):125–131.

86. McLellan, DL, Gaston, MV, Diamond, DA, et al. Anterior urethral valves and diverticula in children: a result of ruptured Cowper’s duct cyst? BJU Int. 2004;94(3):375–378.

87. Arena, S, Romeo, C, Borruto, FA, et al. Anterior urethral valves in children: an uncommon multipathogenic cause of obstructive uropathy. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25(7):613–616.

88. Confer, SD, Galati, V, Frimberger, D, et al. Megacystis with an anterior urethral valve: case report and review of literature. J Pediatr Urol. 2010;6(5):459–462.

89. Jain, P, Mishra, P, Parelkar, S, et al. Anterior urethral valves and diverticulum. Indian J Pediatr. 2009;76(9):943–944.

90. Bates, DG, Coley, BD. Ultrasound diagnosis of the anterior urethral valve. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:634–636.

91. Zia-ul-Miraj, M. Anterior urethral valves: a rare cause of infravesical obstruction in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35(4):556–558.

92. Ozokutan, BH, Kucukaydin, M, Ceylan, H. Congenital scaphoid megalourethra: a report of two cases. Int J Urol. 2005;12:419–421.

93. Ozokutan, BH, Küçükaydin, M, Ceylan, H, et al. Congenital scaphoid megalourethra: report of two cases. Int J Urol. 2005;12(4):419–421.

94. Sharma, AK, Shekhawat, NS, Agarwal, R, et al. Megalourethra: a report of four cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Surg Int. 1997;12(5-6):458–460.

95. Prasad, N, Vivekandhan, KG, Ilangovan, G, et al. Duplication of the urethra. Pediatr Surg Int. 1999;15:419.

96. Salle, JL, Sibai, H, Rosenstein, D, et al. Urethral duplication in the male: review of 16 cases. J Urol. 2000;163:1936.

97. Mane, SB, Obaidah, A, Dhende, NP, et al. Urethral duplication in children: our experience of eight cases. J Pediatr Urol. 2009;5(5):363–367.

98. Erdil, H, Mavi, A, Erdil, S, et al. Urethral duplication. Acta Med Okayama. 2003;57(2):91–93.

99. Coker, AM, Allshouse, MJ, Koyle, MA. Complete duplication of bladder and urethra in a sagittal plane in a male infant: case report and literature review. J Pediatr Urol. 2008;4(4):255–259.

100. Al-Wattar, KM. Congenital prepubic sinus: an epispadiac variant of urethral duplication: case report and review of literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(4):E10.

101. Usami, M, Hayashi, Y, Kojima, Y, et al. Congenital prepubic sinus: a variant of dorsal urethral duplication (Stephens type 3). Int J Urol. 2005;12(2):231–233.

102. Arena, S, Arena, C, Scuderi, MG, et al. Urethral duplication in males: our experience in ten cases. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007;23(8):789–794.

103. Kumaravel, S, Senthilnathan, R, Sankkarabarathi, C. Y-type urethral duplication: an unusual variant of a rare anomaly. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:866–868.

104. Arda, IS, Hiçsönmez, A. An unusual presentation of Y-type urethral duplication with perianal abscess: case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37(8):1213–1215.

105. Sánchez, MM, Vellibre, RM, Castelo, JL, et al. A new case of male Y-type urethral duplication and review of literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(1):e69–e71.

106. Haleblian, G, Kraklau, D, Wilcox, D, et al. Y-type urethral duplication in the male. BJU Int. 2006;97(3):597–602.

107. Wagner, JR, Carr, MC, Bauer, SB, et al. Congenital posterior urethral perineal fistulae: a unique form of urethral duplication. Urology. 1996;48(2):277–280.

108. Islam, MK. Congenital penile urethrocutaneous fistula. Indian J Pediatr. 2001;68(8):785–786.

109. Sharma, AK, Kothari, SK, Menon, P, et al. Congenital H-type rectourethral fistula. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002;18(2-3):193–194.

110. Podesta, ML, Medel, R, Castera, R, et al. Urethral duplication in children: surgical treatment and results. J Urol. 1998;160:1830.

111. Gallentine, ML, Morey, AF. Imaging of the male urethra for stricture disease. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29:361–372.

112. Lendvay, TS, Smith, EA, Kirsch, AJ, et al. Congenital urethral stricture. J Urol. 2002;168(3):1156–1157.

113. Holland, AJ, Cohen, RC, McKertich, KM, et al. Urethral trauma in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2001;17(1):58–61.

114. D’Cruz, R, Soundappan, SS, Cass, DT, et al. Catheter balloon-related urethral trauma in children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2009;45(10):564–566.

115. Kim, B, Kawashima, A, LeRoy, AJ. Imaging of the male urethra. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2007;28(4):258–273.

116. Currarino, G, Stephens, FD. An uncommon type of bulbar urethral stricture, sometimes familial, of unknown cause: congenital versus acquired. J Urol. 1981;126:658.

117. Sugimoto, M, Kakehi, Y, Yamashita, M, et al. Ten cases of congenital urethral stricture in childhood with enuresis. Int J Urol. 2005;12:558–562.

118. Morey, AF, McAninch, JW. Ultrasound evaluation of the male urethra for assessment of urethral stricture. J Clin Ultrasound. 1996;24:473–479.

119. Osman, Y, El-Ghar, MA, Mansour, O, et al. Magnetic resonance urethrography in comparison to retrograde urethrography in diagnosis of male urethral strictures: is it clinically relevant? Eur Urol. 2006;50(3):587–593. [discussion 594].

120. El-Ghar, MA, Osman, Y, Elbaz, E, et al. MR urethrogram versus combined retrograde urethrogram and sonourethrography in diagnosis of urethral stricture. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74(3):e193–e198.

121. Zhang, XM, Hu, WL, He, HX, et al. Diagnosis of male posterior urethral stricture: comparison of 64-MDCT urethrography vs. standard urethrography. Abdom Imaging. 2011;36(6):771–775.

122. Koraitim, MM. On the art of anastomotic posterior urethroplasty: a 27-year experience. J Urol. 2005;173(1):135–139.

123. Mazdak, H, Izadpanahi, MH, Ghalamkari, A, et al. Internal urethrotomy and intraurethral submucosal injection of triamcinolone in short bulbar urethral strictures. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010;42(3):565–568.