Chapter 59 Black Disc

Diagnosis and Treatment of Discogenic Back Pain

The fact that intractable axial back pain may be associated with degenerative changes in the lumbar discs has been recognized for over half a century. Discography was introduced by Lindblom in 19481 to evaluate the disc anatomy for disc herniations. Four years later, Hirsh and Schazowicz2 described the provocation and localization of axial back pain with discography despite a normal myelographic study. Since that time, in spite of a general understanding of the condition, a consensus definition of discogenic back pain has not been achieved.

The lack of consistent terminology to describe symptomatic disc degeneration has added to the controversy. In 1970, Crock3 used the term internal disc disruption as an alternative to describe this process. More recently, the term symptomatic anular tear has been used because of subtle findings on high-resolution MRI and lumbar discography. For consistency in this chapter, we will use the terms discogenic back pain, anular tear, and anular degeneration in reference to symptomatic disc degeneration. Less specific terms such as black disc disease, dark disc disease, postlaminectomy syndrome, and failed back syndrome should be avoided in favor of more specific terminology.

Because of inconsistent terminology and nonstandardized definitions for low back pain, the various causes of back pain have been difficult to differentiate in clinical studies.4 Furthermore, although axial back pain occurs independently of radicular pain in many cases, clinical studies have not routinely distinguished between the causes and treatments of axial back pain as compared with radicular leg pain. Consequently, accurate or reasonable epidemiologic estimates for the incidence, prevalence, or natural history of discogenic back pain as compared with radiculopathy with or without axial back pain are not available.

Causes of Discogenic Pain

Although the most common source of midline axial back pain remains muscular or ligamentous strain, chronic pain associated with specific postural changes can be attributed to either facet joints or intervertebral discs. More specifically, discogenic pain is classically associated with sitting intolerance and flexion of the spine, as compared with pain with spinal extension in cases of facet syndrome. As the body’s largest avascular structure, the intervertebral disc is prone to decreased nutritional uptake and subsequent degeneration. Repetitive motions in the spine from activities of daily life can create shear forces, resulting in microtrauma to the disc. Breakdown of proteoglycans and hydrophilic proteins in the nucleus pulposus leads to disc desiccation, which in turn initiates a cascade of disc height loss, progressive disc collapse, and immobility of the functional spinal unit. This decreased motion may actually lead to mechanical stability through the formation of osteophytes across the affected disc space and gradual resolution of pain, despite continued or progressive degeneration. The natural history and time course of symptoms can vary widely, and a small number of patients remain chronically symptomatic. The dilemma in diagnosis and treatment lies in our lack of understanding of why intervertebral discs with nearly identical morphology can behave differently, some causing patients chronic pain while others remain asymptomatic.5

Progress has been made, however, in understanding the pathophysiology of the lumbar disc as a cause of discogenic pain. The lumbar disc is supplied by a network of pain fibers from the sympathetic chain arising from the sinuvertebral nerve,6 which innervates the outer six layers of the anulus fibrosus.7 With progressive disc collapse, the anulus bulges and tears. Activation of anular nociceptive C-fibers then occurs from direct mechanical stimulation from disc material extending into the outer region of the disc. In addition to causing direct pain, anular tears decrease disc integrity and can cause pathologic loading of the facet joints and end plates, with resultant inflammation. Sprouting of pain fibers into the site of anular injury has also been observed and may be a factor in causing symptoms.8

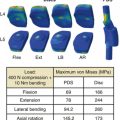

Pressure changes within the disc provide yet another mechanical mechanism that causes discogenic pain. Intradiscal pressures have been shown to be greatest in the sitting position9,10 and correlate with the symptomatic pattern of discogenic pain, which worsens with sitting and resolves with recumbency. Clinically, a lumbar disc herniation can present with an initial history of acute back pain prior to the development of radicular leg pain. Some patients report the resolution of this initial back pain with simultaneous acute new onset of radicular leg pain. Although cause and effect are difficult to prove, it has been postulated that the initial pain from a symptomatic anular tear resolves as internal pressure on the anular pain fibers decreases with herniation of nuclear material into the spinal canal.

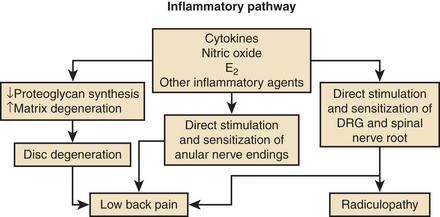

In addition to mechanical sources of pain, a wide variety of putative inflammatory agents, such as phospholipase A2, metallomatrix proteinases, and prostaglandins, have been reported to occur in the nucleus pulposus as part of the degenerative process (Fig. 59-1).11–13 Leakage of these substances into the outer anulus may be another mechanism of pain generation in degenerative disc disease. Exposure of the dorsal root ganglion to these same noxious agents has also been shown to result in histologic damage to the myelin sheaths and ganglion.14,15 This inflammatory process may be the basis of neuropathic pain, which may accompany discogenic pain.

Clinical Presentation

Despite the description of significant pain, the physical examination is usually normal; by definition, the diagnosis of discogenic back pain excludes findings associated with nerve compression. On close observation, the patient may exhibit a tendency for frequent position changes, a relative intolerance to sitting, and pain on forward flexion. The absence of physical findings may prompt the diagnosis of malingering or psychogenic pain. Formal psychometric testing should be used liberally to rule out potential psychosocial issues and to quantify the effect of long-standing pain on coping mechanisms.16,17 Abnormal psychological factors, in addition to the presence of active litigation, tobacco use, and disability, are predictive of a poor outcome with surgical treatment.18 Close observation of the patient at the time of discography can be helpful in further substantiating the presence or absence of psychological risk factors, and some institutions use video recordings for accurate recording of the patient’s response at the time of testing.

In addition to pain of discogenic origin, there are alternative sources of activity-related back pain. Myofascial and ligamentous pain tend to be more superficial, diffuse, and sharp; often have significant local tenderness; and are less associated with sitting intolerance. Facet pain from facet arthropathy typically occurs with extension maneuvers of the spine and improves with flexion. Tumors may present with vague back pain symptoms but are rarely missed with current MRI capabilities. Osteoporotic or pathologic fractures frequently present with isolated back pain but are easily recognized with standard radiographs and CT and with MRI scans in the acute setting. Isthmic spondylolisthesis can result in chronic back pain or be asymptomatic and may present with acute back pain in adolescent patients, while older patients more often present with radiculopathy. An incomplete transitional vertebra syndrome with unilateral or bilateral pseudojoint formation between the enlarged L5 transverse process and sacral ala can also be a potential source of pain and can be easily missed without an angled anteroposterior (Ferguson’s) plain radiograph of the lumbosacral junction.

Diagnostic Imaging

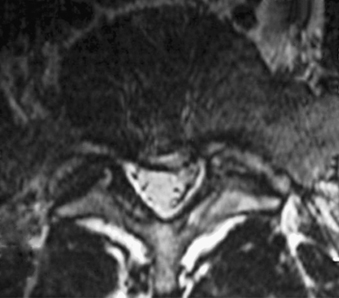

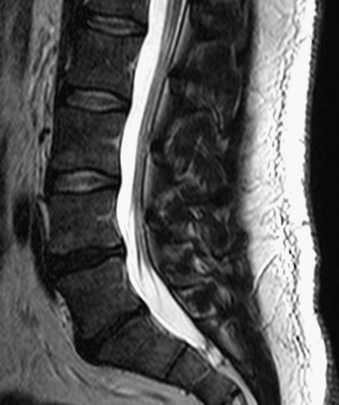

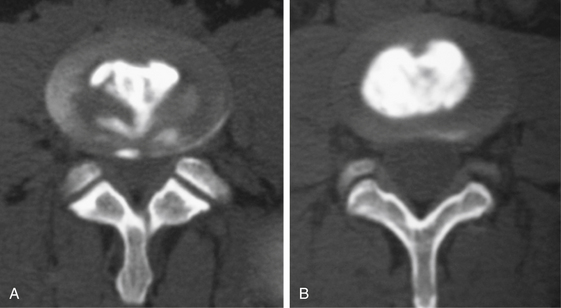

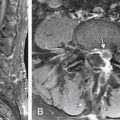

Without specialized testing, discogenic back pain secondary to lumbar degenerative disc disease is not adequately assessed by conventional radiography, CT, and MRI scans. Typical radiographic findings include loss of disc space height, end-plate sclerosis, osteophyte formation, and disc bulge, consistent with spondylosis, which may also be found in asymptomatic patients.19,20 Standard spine radiographs are warranted to rule out spinal instability but are otherwise unhelpful in the diagnosis of symptomatic anular tear. With the advent of MRI, the entire spine can be screened for degenerative processes. While the so-called black disc features nonspecific imaging changes that are consistent with loss of water content (and the disc therefore appears hypointense on T2-weighted imaging), a unique finding referred to as a high-intensity zone (HIZ) in the dorsal anulus has been described on MRI consisting of a discrete hyperintensity within the dorsal anulus.21 The HIZ lesion has been thought to represent either disc material visualized within an anular tear or edema fluid located within the dorsal anulus (Figs. 59-2 and 59-3). While this finding may be suggestive and helpful in localizing the site of pain, it may also be asymptomatic.22–24

Additional MRI findings have been characterized by Modic et al.,25 who described signal changes in the vertebral bodies adjacent to the affected disc space that may have clinical implications correlating with discogenic disease. Modic type I changes are hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2 sequences and signify bone marrow edema. These findings are indicative of acute changes in the vertebral body, have a high specificity for discogenic back pain, and may warrant further workup for the possibility of treatment.26,27 Modic type II changes indicate marrow replacement by fat, are bright on both T1 and T2 sequences, and signify chronic degenerative changes involving the vertebral body and intervertebral disc that are less likely to be associated with discogenic pain.27 Modic type III changes are dark on both T1 and T2 sequences, indicating sclerotic vertebral end plates that are clinically insignificant.

While these MRI findings may be helpful for localization of a potential pain generator, the diagnosis should be confirmed with provocative testing of the disc space via discography.28 With the advent of water-soluble contrast agents and MRI, discography has been used primarily for the evaluation of chronic axial discogenic back pain. Patients with a consistent clinical history who have greater than 50% low back pain compared with lower-extremity pain warrant further investigation with discography.

Discography Technique and Interpretation

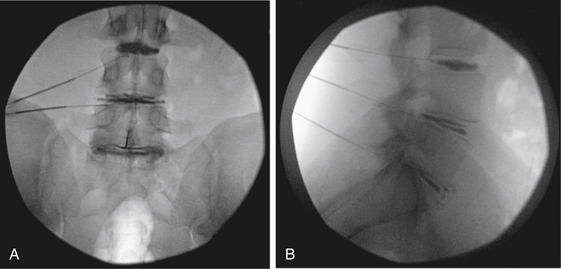

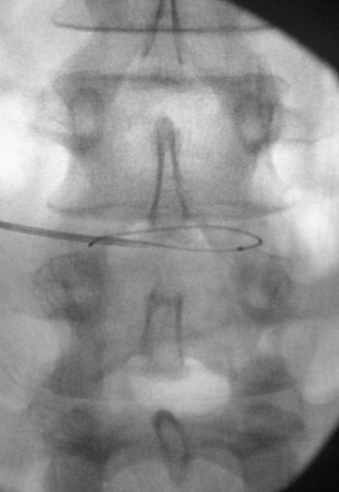

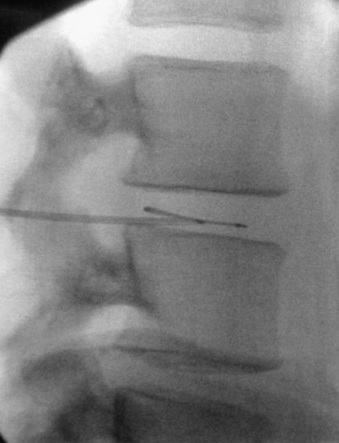

Discography involves the injection of water-soluble iodine contrast into the disc with observation of the contrast pattern, volume of injection, effect of pressure, and, most important, the patient’s pain response (Figs. 59-4 and 59-5). The diagnosis of discogenic pain is made if the patient’s pain is identically and consistently reproduced when the contrast is injected into the disc. While the development of concordant pain is key, equally important is the absence of significant pain from a control level. If lateralizing symptoms are described in the history, reproduction of these lateralizing symptoms at the time of discography may be helpful to determine the level of concordance. The patient’s typical referred pain should not be confused with radiculopathy.

We prefer the two-needle technique, which minimizes the potential for iatrogenic discitis.29 A standard-length 18-gauge spinal needle is first inserted into the interspace of interest. The stylet is then removed, and a 6- to 7-inch 22-gauge spinal needle is placed coaxially through the 18-gauge spinal needle. Placement of the needle tip into the center of the disc space is confirmed with fluoroscopy. Peripheral placement of the needle must be avoided, as an injection into the anular region can result in either a false-positive result or negative pain responses. At L5-S1, entry into the disc space can be difficult because of the limitation of the iliac crests combined with the larger facet joints. Placing a gentle curve in the tip of the 22-gauge needle is usually sufficient for overcoming these anatomic obstacles. Occasionally, a midline transdural approach may be required at L5-S1.

Close observation and recording of the pattern and intensity of the pain response must be done during the discography procedure. The reliability of this information is intimately related to the level and clarity of communication between the patient and physician. Sedation during the test should therefore be minimized and even avoided if possible. A discogram should not be considered positive or concordant without exact reproduction of the patient’s typical pain, and the patient must remain blind to the disc that is tested during the procedure for accurate assessment of results. Injecting local anesthetic into the disc at the end of the procedure may provide pain relief, further increasing the diagnostic sensitivity. With the addition of intradiscal steroids, there can occasionally be a therapeutic advantage. Because of this need for clinical correlation, the operating surgeon may be in the best position to assess the validity of the test, whether through direct performance of the procedure or by review of a video recording of the procedure.16

The various radiographic appearances of the degenerated disc space containing contrast material have been described, and grading systems have been devised.30,31 The observed contrast patterns have not, however, been shown to consistently result in clinical symptoms.31 CT is usually obtained within a few hours after the injection and may help with operative planning by providing information regarding the internal architecture of the disc, localizing anular tears, and offering guidance for minimally invasive surgeries (Fig. 59-6). Postprocedure CT images are especially important in cases with planned percutaneous approaches that involve direct treatment of a demonstrated anular tear.

Surgical Treatment of Discogenic Pain

The surgical treatment of discogenic back pain should be reserved for patients with symptoms that are refractory to conservative management, as most patients will note slow resolution of pain over 3 to 6 months with medical and physical therapy.32,33 Because these patients are neurologically intact, a trial of nonoperative treatment should initially be recommended for all patients.

Various procedural treatment strategies are available for discogenic pain; these have widely differing levels of complexity. Percutaneous treatments are highly desirable from a patient’s standpoint but have a limited application, primarily in the early stages of the degenerative cascade. The lack of advanced disc space collapse during early degenerative disease provides an environment that facilitates the manipulation of catheters, electrodes, and endoscopic instruments within the disc space (Figs. 59-7 and 59-8). These treatments are best suited for younger patients with mild disc collapse who are reluctant to undergo total disc replacement or fusion procedures. Although patients have the advantage of undergoing a less invasive procedure, they must be informed that the efficacy of the treatment varies widely and that the solution might not be long-term. During the effective time frame of treatment, the hope is that the disease will follow the normal natural history and lead to eventual resolution of symptoms. Percutaneous procedures can also be a treatment bridge until such time as more invasive surgical procedures become available or possible.

The potential for direct percutaneous treatment of an internal anular tear has prompted the development of two forms of treatment. Historically, intradiscal electrothermal therapy (IDET) was performed by placing a resistive heating coil catheter into the dorsal anulus.34–36 The coils were heated to 90°C, which increased the temperature of the surrounding anular tissue. With temperatures greater than 45°C, denervation of anular pain fibers occurred, and denaturation of collagen fibers occurred at temperatures above 65°C. The denaturation, through cross-link disruption, results in contraction of collagen fibers and may also promote healing of anular tears. Studies comparing the IDET procedure with sham treatment have had mixed results, showing significant improvements in pain, disability, and depression over placebo in some studies37 and no significant differences between groups in other studies.38 A second similar form of direct treatment involves the intradiscal treatment of anular tears with percutaneous endoscopy and laser anuloplasty, as well as endoscopically guided radiofrequency probes. Reports have indicated the effectiveness of these treatments, but it remains to be seen whether the technique can be standardized and replicated.39,40

For definitive treatment, surgical fusion of the affected disc space can be offered, and multiple studies have substantiated the efficacy of lumbar fusion for the treatment of discogenic pain.41–44 The patients who can expect to achieve the best outcomes from fusion procedures are those who have failed 6 to 12 months of conservative management, have disc degeneration limited to one to two levels, have a clinical history consistent with discogenic pain, and have concordant pain reproduction on discography. Patients who do not sufficiently meet these criteria or who have questionable symptoms from disc degeneration are less likely to have an optimal outcome from operative treatment. Surgery should be approached with caution and avoided in these cases.45

In general, interbody fusion is recommended as the direct treatment for a painful disc, although no significant differences have been reported between fusion techniques.46,47 In theory, interbody fusion has the advantages of directly addressing the pain with removal of the pain generator and providing maximum biomechanical axial support and compression for fusion. This may be achieved with multiple methods, including anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF), posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF), transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF), and extreme lateral interbody fusion (XLIF). Dorsolateral fusion is also an option, especially in cases with advanced disc collapse, but reports of persistent discogenic pain despite development of a solid intertransverse fusion should not be overlooked.47 The relative indications, merits, and techniques of various lumbar fusion procedures are discussed in other chapters of this text. Fusion procedures may be particularly beneficial for patients with advanced spondylosis and disc space collapse with relatively limited spinal mobility. Minimally invasive procedures, such as percutaneous pedicle screw fixation and arthrodesis, may help to increase the success rates by limiting surgical approach morbidity and pain.

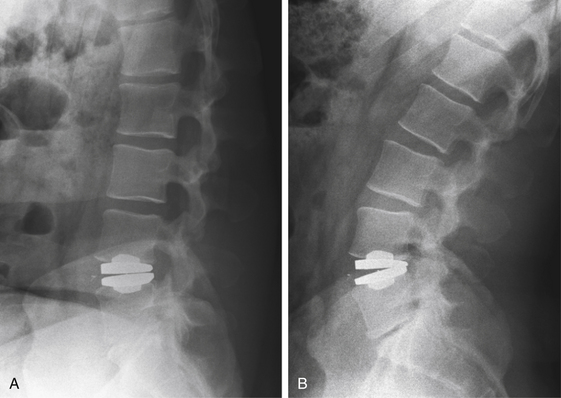

More recently, total disc arthroplasty has emerged as a growing technology and alternative to fusion (Fig. 59-9). For discogenic back pain, total disc replacement has the benefit of removing and replacing the painful intervertebral disc, as with fusion, but with the added advantage of simultaneously preserving spinal mobility. Early results from multiple studies indicate improvements in pain, return to daily activity with the implantation of arthroplasty devices, and low complication rates.48–50 Furthermore, employment and long-term disability rates have shown to be improved with total disc arthroplasty in comparison to interbody fusion.51 This procedure may be considered in most patients with discogenic back pain and may become a primary treatment modality as motion preservation devices continue to improve and advance. Surgeon preference, insurance restrictions, and patient reliability for compliance and follow-up will always be significant factors in decisions about surgical treatment.

Conclusions

Studies reported during the past 25 years have substantiated the existence of discogenic back pain associated with discrete anular tears and diffuse anular degeneration. The literature supports the premise that both mechanical and biochemical factors are involved in the genesis of discogenic pain. Standard diagnostic tests alone are insufficient to make the diagnosis; provocative testing with discography is mandatory. Ultimately, the restoration of biomechanical function, elimination of the painful spinal unit, and avoidance of fusion morbidity should be the goals of future treatment strategies. With the advent of minimally invasive surgical techniques and nonfusion technology, effective treatment for discogenic pain may become a reality.

Crock H.V. The presidential address: ISSLS, internal disc disruption, a challenge to disc prolapse fifty years on. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1986;11:650-653.

Dionne C.E., Dunn K.M., Croft P.R., et al. A consensus approach toward the standardization of back pain definitions for use in prevalence studies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(1):95-103.

Jensen M.C., Brant-Zawadzki M.N., Obuchowski N., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(2):69-73.

Nachemson A., Morris J.M. In vivo measurements of intradiscal pressure: discometry, a method for the determination of pressure in the lower lumbar discs. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1964;46:1077-1092.

Nachemson A., Zdeblick T.A., O’Brien J.P. Lumbar disc disease with discogenic pain: what surgical treatment is most effective? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21(15):1835-1838.

1. Lindblom K. Diagnostic puncture of intervertebral discs in sciatica. Acta Orthop Scand. 1948;17:231-239.

2. Hirsh C., Schazowicz F. Studies on structural changes in the lumbar annulus fibrosus. Acta Orthop Scand. 1952;22:184-223.

3. Crock H.V. The presidential address: ISSLS, internal disc disruption, a challenge to disc prolapse fifty years on. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1986;11:650-653.

4. Dionne C.E., Dunn K.M., Croft P.R., et al. A consensus approach toward the standardization of back pain definitions for use in prevalence studies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(1):95-103.

5. Nachemson A., Zdeblick T.A., O’Brien J.P. Lumbar disc disease with discogenic pain: what surgical treatment is most effective? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21(15):1835-1838.

6. Edgar M.A., Ghadially J.A. Innervation of the lumbar spine. Clin Orthop. 1976;115::35-41.

7. Gronblad M., Weinstein J.N., Santavirta S. Immunohistochemical observations on spinal tissue innervation: a review of hypothetical mechanisms of back pain. Acta Orthop Scand. 1991;62(6):614-622.

8. Coppes M.H., Marani E., Thomeer R.T., et al. Innervation of “painful” lumbar discs. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22(20):2342-2349. discussion 2349–2350

9. Nachemson A., Morris J. Lumbar discometry: lumbar intradiscal pressure measurements in vivo. Lancet. 1963;1(7291):1140-1142.

10. Nachemson A., Morris J.M. In vivo measurements of intradiscal pressure: discometry, a method for the determination of pressure in the lower lumbar discs. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1964;46:1077-1092.

11. Gronblad M., Virri J., Ronkko S., et al. A controlled biochemical and immunohistochemical study of human synovial-type (group II) phospholipase A2 and inflammatory cells in macroscopically normal, degenerated, and herniated human lumbar disc tissues. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21(22):2531-2538.

12. Saal J.S., Franson R.C., Dobrow R., et al. High levels of inflammatory phospholipase A2 activity in lumbar disce herniations. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990;15:674-678.

13. Kang J.D., Stefanovic-Racic M., McIntyre L.A., et al. Toward a biochemical understanding of human intervertebral disc degeneration and herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22(10):1065-1073.

14. Chen C., Cavanaugh J.M., Ozaktay A.C., et al. Effects of phospholipase A2 on lumbar nerve root structure and function. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22(10):1057-1064.

15. Kawakami M., Tamaki T., Hashizume H., et al. The role of phospholipase A2 and nitric oxide in pain-related behavior produced by an allograft of intervertebral disc material to the sciatic nerve of the rat. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1977;22(10):1074-1079.

16. Walker J.3rd, El Abd O., Isaac Z., et al. Discography in practice: a clinical and historical review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1(2):69-83.

17. Block A.R., Vanharanta H., Ohnmeiss D.D., et al. Discographic pain report: influence of psychological factors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21(3):334-338.

18. Carragee E.J. Is lumbar discography a determinate of discogenic low back pain: provocative discography reconsidered. Curr Rev Pain. 2000;4(4):301-308.

19. Witt I., Vestergaard A., Rosenklint A. A comparative analysis of x-ray findings of the lumbar spine in patients with and without lumbar pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1984;9(3):298-300.

20. Jensen M.C., Brant-Zawadzki M.N., Obuchowski N., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(2):69-73.

21. Schellhas K.P., Pollei S.R., Gundry C.R., et al. Lumbar disc high-intensity zone: correlation of magnetic resonance imaging and discography. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21(1):79-86.

22. Lam K.S., Carlin D., Mulholland R.C. Lumbar disc high-intensity zone: the value and significance of provocative discography in the determination of the discogenic pain source. Eur Spine J. 2000;9(1):36-41.

23. Carragee E.J., Paragioudakis S.J., Khurana S. 2000 Volvo Award winner in clinical studies: lumbar high-intensity zone and discography in subjects without low back problems. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(23):2987-2992.

24. Ito M., Incorvaia K.M., Yu S.F., et al. Predictive signs of discogenic lumbar pain on magnetic resonance imaging with discography correlation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998;23(11):1252-1258. discussion 1259–1260

25. Modic M.T., Steinberg P.M., Ross J.S., et al. Degenerative disk disease: assessment of changes in vertebral body marrow with MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;166(1 Pt 1):193-199.

26. Braithwaite I., White J., Saifuddin A., et al. Vertebral end-plate (Modic) changes on lumbar spine MRI: correlation with pain reproduction at lumbar discography. Eur Spine J. 1998;7(5):363-368.

27. Weishaupt D., Zanetti M., Hodler J., et al. Painful lumbar disk derangement: relevance of endplate abnormalities at MR imaging. Radiology. 2001;218(2):420-427.

28. Guyer R.D., Ohnmeiss D.D. Lumbar discography: position statement from the North American Spine Society Diagnostic and Therapeutic Committee [see comments]. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(18):2048-2059.

29. Fraser R.D., Osti O.L., Vernon-Roberts B. Discitis after discography. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1987;69(1):26-35.

30. Sachs B.L., Vanharanta H., Spivey M.A., et al. Dallas discogram description: a new classification of CT/discography in low-back disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1987;12(3):287-294.

31. Osti O.L., Vernon-Roberts B., Moore R., et al. Annular tears and disc degeneration in the lumbar spine: a post-mortem study of 135 discs. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1992;74(5):678-682.

32. Mannion A.F., Muntener M., Taimela S., et al. A randomized clinical trial of three active therapies for chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24(23):2435-2448.

33. van Tulder M.W., Koes B.W., Bouter L.M. Conservative treatment of acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the most common interventions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22(18):2128-2156.

34. Saal J.A., Saal J.S. Intradiscal electrothermal treatment for chronic discogenic low back pain: a prospective outcome study with minimum 1-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(20):2622-2627.

35. Saal J.A., Saal J.S. Intradiscal electrothermal treatment for chronic discogenic low back pain: prospective outcome study with a minimum 2-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(9):966-973. discussion 973–974

36. Saal J.S., Saal J.A. Management of chronic discogenic low back pain with a thermal intradiscal catheter: a preliminary report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(3):382-388.

37. Pauza K.J., Howell S., Dreyfuss P., et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of intradiscal electrothermal therapy for the treatment of discogenic low back pain. Spine J. 2004;4(1):27-35.

38. Freeman B.J., Fraser R.D., Cain C.M., et al. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial: intradiscal electrothermal therapy versus placebo for the treatment of chronic discogenic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(21):2369-2377. discussion 2378

39. Lee S.H., Kang H.S. Percutaneous endoscopic laser annuloplasty for discogenic low back pain. World Neurosurg. 2010;;73:198-206. discussion E33

40. Yeung A.T., Tsou P.M. Posterolateral endoscopic excision for lumbar disc herniation: surgical technique, outcome, and complications in 307 consecutive cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(7):722-731.

41. Herkowitz H.N., Sidhu K.S. Lumbar spine fusion in the treatment of degenerative conditions: current indications and recommendations. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3(3):123-135.

42. Fritzell P., Hagg O., Wessberg P., et al. 2001 Volvo Award Winner in Clinical Studies: lumbar fusion versus nonsurgical treatment for chronic low back pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(23):2521-2532. discussion 2532–2534

43. Lee C.K., Vessa P., Lee J.K. Chronic disabling low back pain syndrome caused by internal disc derangements. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(3):356-361.

44. Rodts G.E.Jr., Mummaneni P. Discogenic back pain: the case for surgery. Clin Neurosurg. 2004;51:277-280.

45. Zdeblick T.A. The treatment of degenerative lumbar disorders. A critical review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(Suppl 24):S126-S137.

46. Fritzell P., Hagg O., Wessberg P., et al. Chronic low back pain and fusion: a comparison of three surgical techniques: a prospective multicenter randomized study from the Swedish lumbar spine study group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(11):1131-1141.

47. O’Brien J.P., Dawson M.H., Heard C.W., et al. Simultaneous combined anterior and posterior fusion. A surgical solution for failed spinal surgery with a brief review of the first 150 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;203::191-195.

48. Bertagnoli R., Kumar S. Indications for full prosthetic disc arthroplasty: a correlation of clinical outcome against a variety of indications. Eur Spine J. 2002;11(Suppl 2):S131-S136.

49. Delamarter R.B., Fribourg D.M., Kanim L.E., et al. ProDisc artificial total lumbar disc replacement: introduction and early results from the United States clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(20):S167-S175.

50. Gamradt S.C., Wang J.C. Lumbar disc arthroplasty. Spine J. 2005;5(1):95-103.

51. Guyer R.D., McAfee P.C., Banco R.J., et al. Prospective, randomized, multicenter Food and Drug Administration investigational device exemption study of lumbar total disc replacement with the CHARITE artificial disc versus lumbar fusion: five-year follow-up. Spine J. 2009;9(5):374-386.