Chapter 37 Bioterrorism

2 What are some possible agents that might be used in an attack?

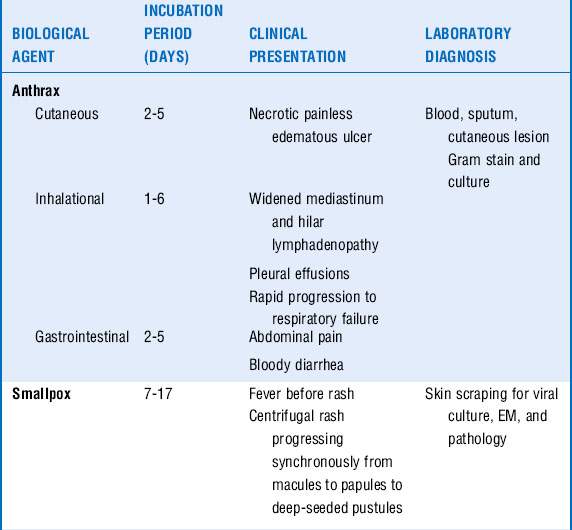

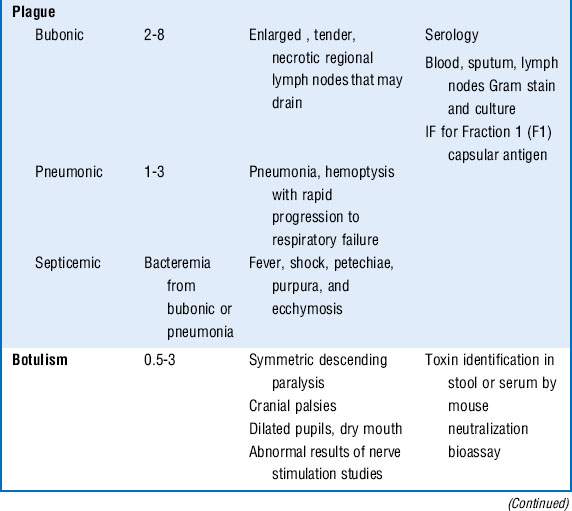

The CDC classifies six pathogens as class A bioterrorism agents: smallpox, plague, botulism, tularemia, viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF), and anthrax. These agents are considered to have the greatest potential for mass casualties, large-scale dissemination, and public panic and social disruption. All of them except VHF have been developed as biological weapons. They are stable in aerosol form and would be most likely delivered in this manner. Most of the civilian population remains susceptible to them, and most cause illnesses not typically seen by providers, causing delayed or missed diagnoses. The major clinical syndromes are summarized in Table 37-1.

3 What are clues to a biological attack?

Recognition of a biological attack may be delayed until patients begin accessing medical care, which may be days to weeks after the event depending on the incubation period of the pathogen (Table 37-1). Features that might suggest a biological attack include the following:

Any unusual increase or clustering of patients being seen with clinical symptoms that suggest an infectious disease outbreak

Any unusual increase or clustering of patients being seen with clinical symptoms that suggest an infectious disease outbreak

A suspected or confirmed communicable disease in a nonendemic area, for example, plague in New England

A suspected or confirmed communicable disease in a nonendemic area, for example, plague in New England

An unusual age distribution of a common disease

An unusual age distribution of a common disease

An unusual temporal and/or geographic clustering of illness, for example, persons who attended the same ball game or parade

An unusual temporal and/or geographic clustering of illness, for example, persons who attended the same ball game or parade

Simultaneous outbreaks in humans and animals (all class A agents with the exception of smallpox infect animals)

Simultaneous outbreaks in humans and animals (all class A agents with the exception of smallpox infect animals)

An unusual seasonal distribution of illness, for example, influenza-like symptoms in summer

An unusual seasonal distribution of illness, for example, influenza-like symptoms in summer

4 What pathogens would present with respiratory failure?

Anthrax: Pneumonic anthrax is caused by the inhalation of the spore form of Bacillus anthracis. It begins as a nonspecific influenza-like illness with fever, cough, malaise, headache, and vomiting. Rapid progression occurs to hemorrhagic mediastinitis, hilar lymph node enlargement, respiratory failure, hemodynamic collapse, and death. Although chest radiographs classically show only a widened mediastinum without pulmonary infiltrates, several of the victims from the anthrax letter attacks in the fall of 2001 did have pulmonary infiltrates and pleural effusions. Bacteremia and meningitis can occur.

Anthrax: Pneumonic anthrax is caused by the inhalation of the spore form of Bacillus anthracis. It begins as a nonspecific influenza-like illness with fever, cough, malaise, headache, and vomiting. Rapid progression occurs to hemorrhagic mediastinitis, hilar lymph node enlargement, respiratory failure, hemodynamic collapse, and death. Although chest radiographs classically show only a widened mediastinum without pulmonary infiltrates, several of the victims from the anthrax letter attacks in the fall of 2001 did have pulmonary infiltrates and pleural effusions. Bacteremia and meningitis can occur.

Plague: Pneumonic plague, caused by Yersinia pestis, can develop secondarily from bubonic plague via hematogenous dissemination from involved lymph nodes or primarily from inhalation of the plague bacillus. Patients are seen with the sudden onset of headache, fever, shortness of breath, cough, and hemoptysis. Chest radiographs most often reveal bilateral bronchopneumonia. There may be leukocytosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and elevated liver function test results. Rapid progression to respiratory failure and shock ensues.

Plague: Pneumonic plague, caused by Yersinia pestis, can develop secondarily from bubonic plague via hematogenous dissemination from involved lymph nodes or primarily from inhalation of the plague bacillus. Patients are seen with the sudden onset of headache, fever, shortness of breath, cough, and hemoptysis. Chest radiographs most often reveal bilateral bronchopneumonia. There may be leukocytosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and elevated liver function test results. Rapid progression to respiratory failure and shock ensues.

Tularemia: If Francisella tularensis is inhaled, a syndrome similar to community-acquired pneumonia develops with fever, myalgias, headache, pleuritic chest pain, and a dry cough. Concomitant pharyngitis may be present. Some patients demonstrate a pulse-temperature deficit, where an increase in temperature is not accompanied by a relative increase in heart rate. Chest radiographs may have a variety of findings including unilateral or bilateral pneumonia, hilar lymphadenopathy, pleural effusions, and, less often, parenchymal cavitation.

Tularemia: If Francisella tularensis is inhaled, a syndrome similar to community-acquired pneumonia develops with fever, myalgias, headache, pleuritic chest pain, and a dry cough. Concomitant pharyngitis may be present. Some patients demonstrate a pulse-temperature deficit, where an increase in temperature is not accompanied by a relative increase in heart rate. Chest radiographs may have a variety of findings including unilateral or bilateral pneumonia, hilar lymphadenopathy, pleural effusions, and, less often, parenchymal cavitation.

5 What pathogens would present with shock?

Anthrax and plague may present with shock coupled with pneumonia and respiratory failure.

Anthrax and plague may present with shock coupled with pneumonia and respiratory failure.

VHF can be caused by a diverse group of RNA viruses including Ebola, Marburg, Lassa fever, and Rift Valley fever from sub-Sahara Africa, in addition to Junin virus, Machupo virus, Guanarito virus, and Sabia virus from South America. These are all capable of causing a wide spectrum of illness ranging from asymptomatic to life threatening. As the name implies, these viruses cause fever and a bleeding diathesis. Patients typically are seen with an acute febrile illness associated with headache, fatigue, myalgias, abdominal pain, diarrhea, rash, pharyngitis, and hypotension. Bleeding can range from mild conjunctival hemorrhage to severe mucocutaneous bleeding. Progression to shock occurs in severe cases, and patients typically die of septic shock rather than blood loss.

VHF can be caused by a diverse group of RNA viruses including Ebola, Marburg, Lassa fever, and Rift Valley fever from sub-Sahara Africa, in addition to Junin virus, Machupo virus, Guanarito virus, and Sabia virus from South America. These are all capable of causing a wide spectrum of illness ranging from asymptomatic to life threatening. As the name implies, these viruses cause fever and a bleeding diathesis. Patients typically are seen with an acute febrile illness associated with headache, fatigue, myalgias, abdominal pain, diarrhea, rash, pharyngitis, and hypotension. Bleeding can range from mild conjunctival hemorrhage to severe mucocutaneous bleeding. Progression to shock occurs in severe cases, and patients typically die of septic shock rather than blood loss.

7 What pathogens may present with predominantly cutaneous manifestations?

Smallpox, caused by the DNA virus variola major, is acquired via inhalation of infectious droplets aerosolized by affected patients. Typically a prodrome of fever, chills, myalgias, and headache occurs over 2 to 4 days, followed by the eruption of intraoral macules. A maculopapular rash develops on the face, which then progresses in a centrifugal manner to involve the extremities and finally the trunk. The rash progresses to deep-seated vesicles and pustules over 8 to 10 days. Complications include bacterial superinfections, fluid and electrolyte abnormalities, desquamation, panophthalmitis, residual scarring, and death. Secondary bacterial infections involving the skin or lungs may occur and are often complicated by bacteremia and sepsis.

Smallpox, caused by the DNA virus variola major, is acquired via inhalation of infectious droplets aerosolized by affected patients. Typically a prodrome of fever, chills, myalgias, and headache occurs over 2 to 4 days, followed by the eruption of intraoral macules. A maculopapular rash develops on the face, which then progresses in a centrifugal manner to involve the extremities and finally the trunk. The rash progresses to deep-seated vesicles and pustules over 8 to 10 days. Complications include bacterial superinfections, fluid and electrolyte abnormalities, desquamation, panophthalmitis, residual scarring, and death. Secondary bacterial infections involving the skin or lungs may occur and are often complicated by bacteremia and sepsis.

Bubonic plague presents as an acute bacterial lymphadenitis with fever and chills. Enlarged lymph nodes, called buboes, can enlarge to up to 10 cm and may suppurate and drain. A secondary bacteremic phase may follow with sepsis, DIC, purpura, and gangrene of the distal extremities.

Bubonic plague presents as an acute bacterial lymphadenitis with fever and chills. Enlarged lymph nodes, called buboes, can enlarge to up to 10 cm and may suppurate and drain. A secondary bacteremic phase may follow with sepsis, DIC, purpura, and gangrene of the distal extremities.

8 What initial steps should be taken if a patient is suspected to be a victim of a bioterrorist attack?

If the biological agent is known, appropriate isolation and infection control measures should be implemented as outlined in Table 37-2.

Table 37-2 Infection Control for Category a Biological Weapons

| Disease | Mode of transmission | Precautions |

|---|---|---|

| Anthrax | ||

| Pulmonary | Inhalation of spores |

9 What infection control measures need to be taken in the ICU?

The biological agents that pose a transmission threat to health care workers in the ICU include smallpox, plague, and VHFs. Anthrax, botulism, and tularemia are not transmissible to health care workers in the ICU setting. See Table 37-2. Infection control precautions include the following:

Standard: Gown and/or gloves if contact with body secretions is expected and mask or face shield if facial splash may occur. Hand hygiene before and after patient contact is required.

Standard: Gown and/or gloves if contact with body secretions is expected and mask or face shield if facial splash may occur. Hand hygiene before and after patient contact is required.

Contact: Standard precautions plus the wearing of gowns and gloves when entering the room and mask or face shield if facial splash expected.

Contact: Standard precautions plus the wearing of gowns and gloves when entering the room and mask or face shield if facial splash expected.

Droplet: Standard precautions plus wearing a surgical mask if within 3 to 6 feet of the patient in a private room.

Droplet: Standard precautions plus wearing a surgical mask if within 3 to 6 feet of the patient in a private room.

Airborne: Place patient in negative pressure room, and use fit-tested N95 respirator or PAPR.

Airborne: Place patient in negative pressure room, and use fit-tested N95 respirator or PAPR.

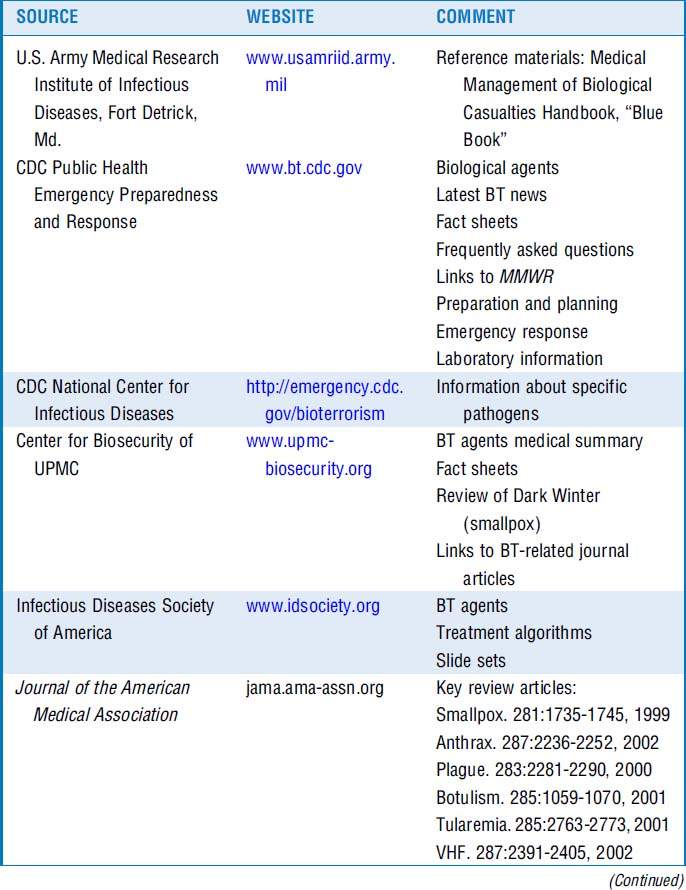

10 How should the patient be treated (Table 37-3)?

Anthrax: Cutaneous anthrax can usually be treated with prolonged oral antibiotics for 60 days. Pneumonic anthrax and severe cutaneous disease should initially be treated with intravenous ciprofloxacin or doxycycline coupled with one or two additional agents such as vancomycin, rifampin, or imipenem-cilastatin. Transition to oral ciprofloxacin or doxycycline can be made when the patient is clinically stable. Total treatment should last for 60 days.

Anthrax: Cutaneous anthrax can usually be treated with prolonged oral antibiotics for 60 days. Pneumonic anthrax and severe cutaneous disease should initially be treated with intravenous ciprofloxacin or doxycycline coupled with one or two additional agents such as vancomycin, rifampin, or imipenem-cilastatin. Transition to oral ciprofloxacin or doxycycline can be made when the patient is clinically stable. Total treatment should last for 60 days.

Smallpox: Supportive care is the mainstay. Both cidofovir and imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) may have activity.

Smallpox: Supportive care is the mainstay. Both cidofovir and imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) may have activity.

Plague: Intravenous antibiotics should be administered for 7 days.

Plague: Intravenous antibiotics should be administered for 7 days.

Tularemia: Intravenous antibiotics should be given for 10 to 14 days.

Tularemia: Intravenous antibiotics should be given for 10 to 14 days.

Botulism: Although passive immunization with equine antitoxin is helpful in naturally occurring botulism, it may be of limited usefulness in a terrorist attack because it may not be effective if used more than a few hours after exposure.

Botulism: Although passive immunization with equine antitoxin is helpful in naturally occurring botulism, it may be of limited usefulness in a terrorist attack because it may not be effective if used more than a few hours after exposure.

VHF: Therapy is limited. Ribavirin intravenously may have some efficacy against Lassa fever, New World arenaviruses, and Rift Valley fever.

VHF: Therapy is limited. Ribavirin intravenously may have some efficacy against Lassa fever, New World arenaviruses, and Rift Valley fever.

11 What postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) should be used?

PEP against the category A agents is summarized in Table 37-3.

| Pathogen | Treatment | Postexposure prophylaxis (all administered orally) |

|---|---|---|

| Anthrax | ||

bid, Twice daily; IV, intravenously; PO, orally; tid, three times daily.

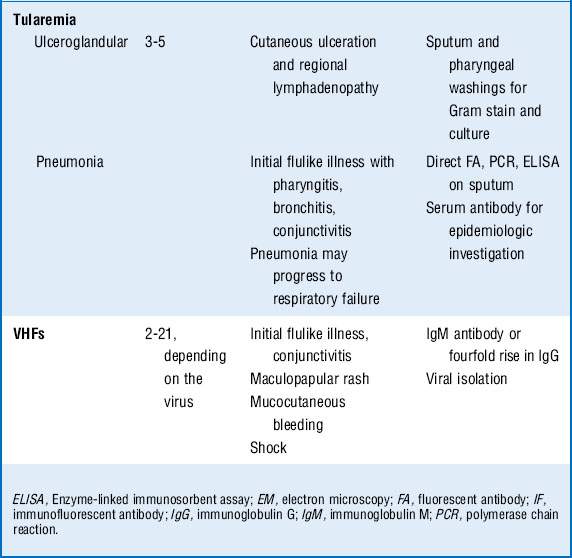

12 What web-based resources can I access?

Resources are listed in Table 37-4.

Key Points Clues to Recognition of a Biological Attack

Clues to Recognition of a Biological Attack

1 Arnon S.S., Schechter R., Ingelsby T.V., et al. Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon. JAMA. 2001;285:1059–1070.

2 Dennis D.T., et al. Tularemia as a biological weapon. In: Henderson D.A., Inglesby T.V., O’Toole T. Bioterrorism: Guidelines for Medical and Public Health Management. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2002:611–626.

3 Franz D.R., Jahrling P.B., Friedlander A.M., et al. Clinical recognition and management of patients exposed to biological warfare agents. JAMA. 1997;278:399–411.

4 Henderson D.A., Inglesby T.V., Bartlett J.G., et al. Smallpox as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA. 1999;281:2127–2137.

5 Inglesby T.V., Dennis D.T., Henderson D.A., et al. Plague as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA. 2000;283:2281–2290.

6 Inglesby T.V., O’Toole T., Henderson D.A., et al. Anthrax as a biological weapon, 2002: updated recommendations for management. JAMA. 2002;287:2236–2252.

7 Jernigan D.B., Ragunathan P.L., Bell B.P., et al. Investigation of bioterrorism-related anthrax, United States, 2001: epidemiologic findings. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:1019–1028.

8 Management of patients with suspected viral hemorrhagic fever—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44:475–479.

9 Miller J.M. Agents of bioterrorism. Preparing for bioterrorism at the community level. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001;15:1127–1156.

10 Waterer G.W., Robertson H. Bioterrorism for the respiratory physician. Respirology. 2009;14:5–11.