Chapter 704 Biologic and Chemical Terrorism

Epidemiology and Pediatric-Specific Concerns

Large-scale attacks on civilian targets will likely involve pediatric victims, and children may be more susceptible than adults to the effects of certain biologic and chemical agents (Chapters 699 and 700). Thinner skin makes dermally active chemical agents, such as mustard, a greater risk to children than adults. A larger surface area per unit volume further increases the problem. A small relative blood volume makes children more susceptible to the volume losses associated with enteric infections such as cholera and to gastrointestinal intoxications such as might be seen with exposure to the staphylococcal enterotoxins. Children’s relatively higher minute ventilation than that of adults increases the threat of agents delivered via the inhalational route. The fact that children live “closer to the ground” compounds this effect when heavier-than-air chemicals are involved. An immature blood-brain barrier may heighten the risk of central nervous system toxicity from nerve agents. Finally, developmental considerations make it less likely that a child would readily flee an area of danger, thereby increasing exposure to these various adverse effects.

Children also may experience unique disease manifestations not seen in adults; suppurative parotitis is a common characteristic occur among children with melioidosis but is not generally seen in adults with Burkholderia pseudomallei infection (Chapter 197.2).

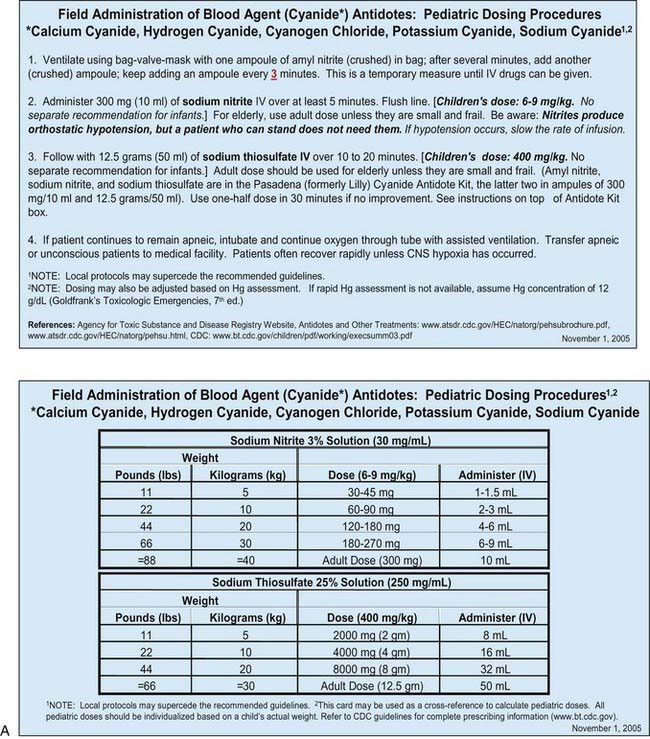

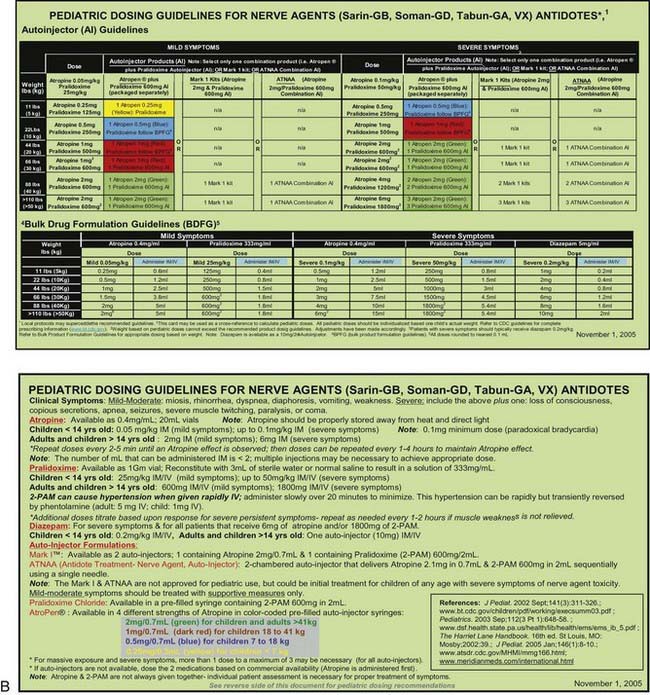

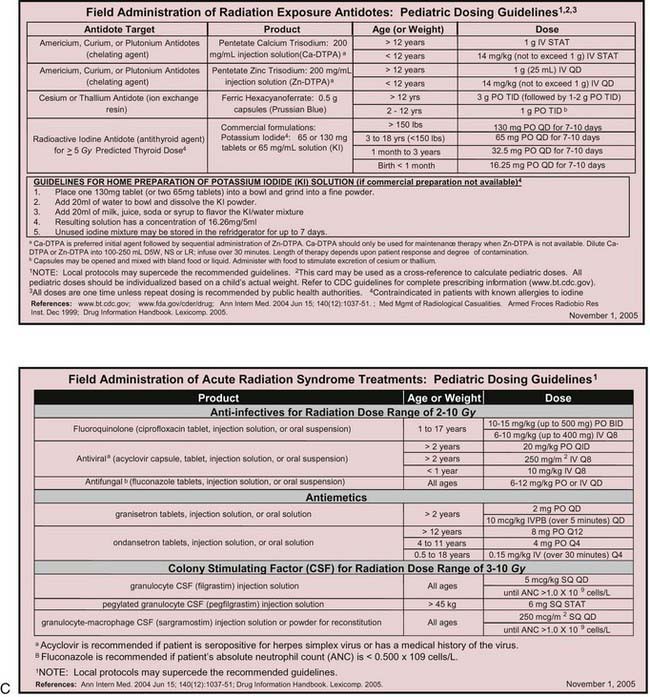

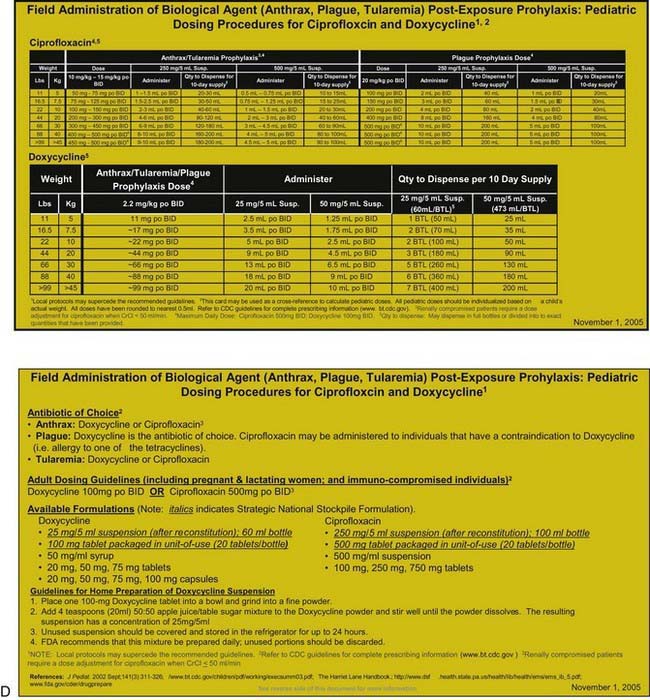

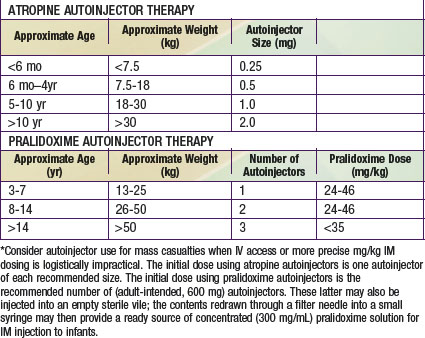

Many otherwise useful pharmaceutical agents are not available in pediatric dosing regimens. The military distributes nerve agent antidote kits consisting of prefilled autoinjectors designed for the rapid administration of atropine and pralidoxime. Many emergency departments and some ambulances stock these kits. The doses of agents contained in the nerve agent antidote kit are calculated for soldiers and thus are far in excess of those appropriate for young children, and pediatric pralidoxime autoinjectors are not yet available. Atropine autoinjectors specifically formulated for children have been approved by the FDA and are now widely available. To facilitate accurate field post-exposure dose administration for children based on age, weight, and level of exposure, the U.S. Public Health Service has prepared four pocket-sized “Weapons of Mass Destruction Pediatric Dosing Cards” for biologic agents, nerve agents, cyanide, and radiation (Fig. 704-1).

Clinical Manifestations

In the event of a terrorist attack, clinicians may be called on to make prompt diagnoses and render rapid life-saving treatments before the results of confirmatory diagnostic tests are available. Although each potential agent of terrorism produces its own unique clinical manifestations, it is useful to consider their effects in terms of a limited number of distinct clinical syndromes. This approach helps clinicians make prompt, rational decisions regarding empirical therapy. In general, casualties from a terrorist attack experience symptoms immediately upon exposure to an agent (or within the first several hours after exposure) or, alternatively, symptoms develop slowly over a period of days to weeks. In the former case, the sinister nature of the event is often obvious, and the etiology more likely to be conventional or chemical in nature. Biologic agents differ from conventional, chemical, and nuclear weapons (Chapters 699 and 700) in that they have inherent incubation periods. Patients are therefore likely to present removed in time and place from the point of an unannounced and unnoticed exposure to a biologic agent. Whereas traditional first responders such as firemen and paramedics may be at the forefront of a conventional or chemical terrorism response, the primary care physician is likely to constitute the first line of defense against the effects of a biologic agent.

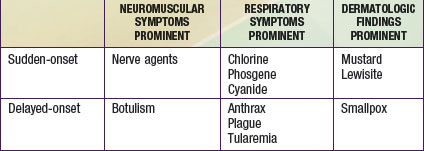

Casualties can thus be categorized as either immediate or delayed in presentation. Within each of these categories, patients can be further classified as having primarily respiratory, neuromuscular, or dermatologic manifestations (Table 704-1). A limited number of agents may cause each particular syndrome, permitting institution of empiric therapy targeted at a short list of potential etiologies. The viral hemorrhagic fevers might manifest as fever and a bleeding diathesis; these agents are considered separately in Chapter 263. In most cases, supportive care is the mainstay of hemorrhagic fever treatment.

Sudden-Onset Neuromuscular Syndrome: Nerve Agents

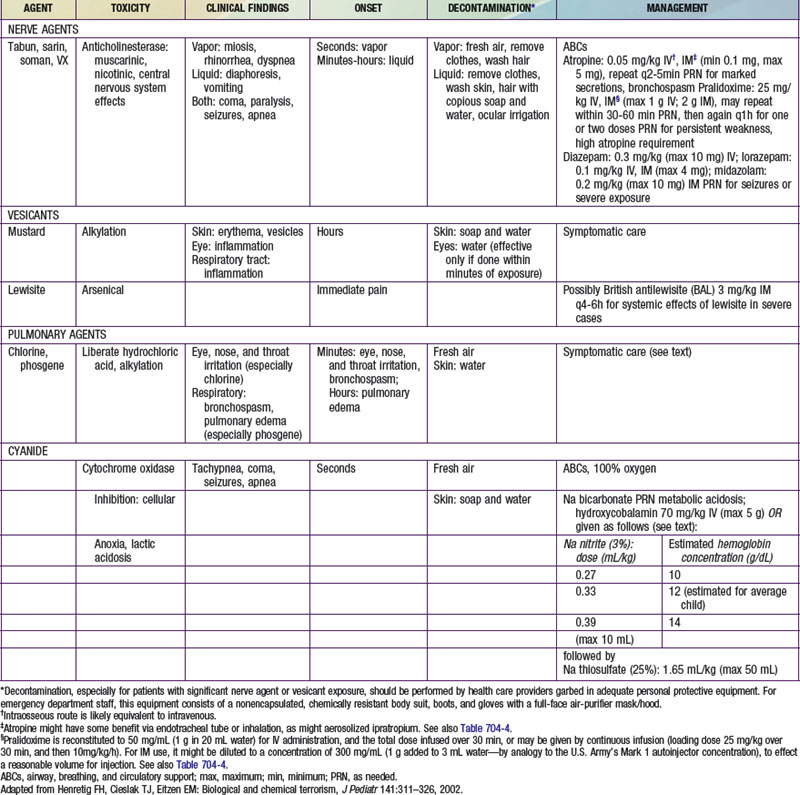

The very rapid onset of neuromuscular symptoms after an exposure should lead the clinician to consider nerve agent intoxication. The nerve agents (tabun, sarin, soman, and VX) are organophosphate analogues of common pesticides that act as potent inhibitors of the enzyme acetylcholinesterase. They are hazardous via ingestion, inhalation, or cutaneous absorption (Chapter 58).

Delayed-Onset Neuromuscular Syndrome: Botulism

The delayed onset (hours to days after exposure) of neuromuscular symptoms is characteristic of botulism. Botulism occurs after exposure to one of seven related neurotoxins produced by certain strains of Clostridium botulinum, a strictly anaerobic, spore-forming, gram-positive bacillus commonly found in soil. Naturally occurring botulism (Chapter 202) usually follows ingestion of preformed toxin (food poisoning) or results from intestinal toxin production (infantile botulism). An aerosol exposure would likely result in a case of clinical botulism indistinguishable from that caused by natural exposures.

Sudden-Onset Respiratory Syndrome: Chlorine, Phosgene, and Cyanide

Cyanide is a cellular poison, with protean clinical manifestations. Initially, cyanide toxicity is most likely to manifest as tachypnea and hyperpnea, progressing rapidly to apnea in cases with significant exposure (Chapter 58). The efficacy of cyanide as a chemical terrorism agent is limited by its volatility in open air and relatively low lethality in comparison with nerve agents. Released in a closed room, however, cyanide could have devastating effects, as evidenced by its use in the Nazi gas chambers during World War II. Cyanide inhibits cytochrome a3, interfering with normal mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and leading to cellular anoxia and lactic acidosis. In addition to respiratory distress, early findings among cyanide victims include tachycardia, flushing, dizziness, headache, diaphoresis, nausea, and vomiting. With greater exposure, seizures, coma, apnea, and cardiac arrest may follow within minutes. An elevated anion gap metabolic acidosis is typically present, and decreased peripheral oxygen utilization leads to an elevated mixed venous oxygen saturation value.

Delayed-Onset Respiratory Syndrome: Anthrax, Plague, and Tularemia

Whereas inhalational anthrax is a disease primarily of mediastinal lymphatic tissue, exposure to aerosolized plague bacilli typically leads to a primary pneumonia. Endemic plague is usually transmitted via the bites of fleas and is discussed in Chapter 195.3. The causative organism of all forms of human plague, Yersinia pestis, is a bipolar-staining, gram-negative facultative intracellular bacillus. An ability to survive within the macrophage aids its dissemination to distant sites following inoculation or inhalation. “Buboes,” markedly swollen, tender regional lymph nodes in the distribution of a bite, are the hallmark feature of bubonic plague. Fever and malaise are typically present, and septicemia often develops as bacteria gain access to the circulation. Petechiae, purpura, and overwhelming disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) commonly occur, and 80% of bubonic plague victims ultimately have positive blood culture results. Plague is extremely infective and lethal, as illustrated by the fact that the “Black Death” eliminated one third of the population of Europe during the Middle Ages. Even then, the potential of bubonic plague as a weapon was appreciated, as evidenced by its intentional use in 1346 by invading Tatars against the garrison at Kaffa in the Ukraine.

Tularemia is a highly infectious disease caused by the gram-negative coccobacillus Francisella tularensis. Naturally occurring tularemia is discussed in Chapter 198. The high degree of infectivity of F. tularensis (<10 organisms are thought to be necessary to produce infection via inhalation), as well as its survivability in the environment, contributes to its inclusion on the list of agents of concern. Several clinical forms of endemic tularemia are known, but inhalational exposure resulting from a terrorist attack would likely lead to a plaguelike primary pneumonia or to typhoidal tularemia, manifesting as a variety of nonspecific symptoms including fever, malaise, and abdominal pain.

Prevention

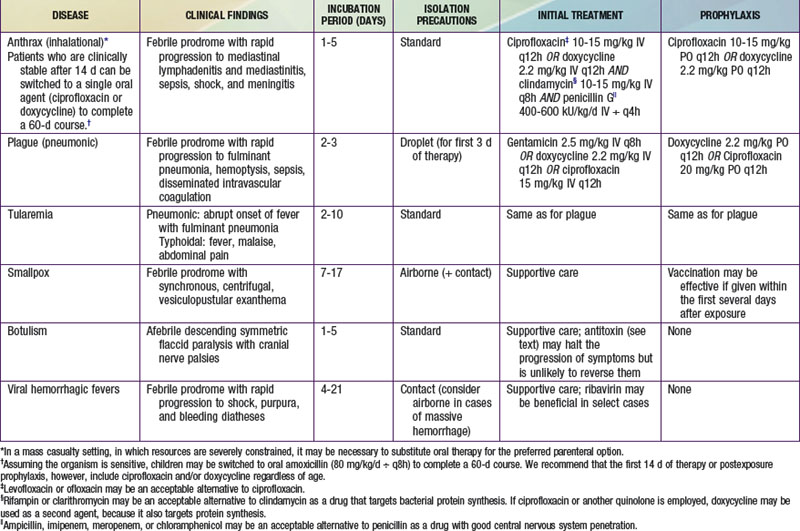

Anthrax vaccine might similarly be employed in a postexposure setting. Some authorities recommend three doses of this vaccine as an adjunct to postexposure chemoprophylaxis after documented exposure to aerosolized anthrax spores. Nonetheless, postexposure administration of oral antibiotics constitutes the mainstay of management for asymptomatic victims believed to have been exposed to anthrax as well as to other bacterial agents such as plague and tularemia. Appropriate prophylactic regimens for various biologic exposures are provided in Table 704-2.

Treatment

Recommended therapies for overt diseases caused by various chemical and biologic agents are provided in Tables 704-2 and 704-3. It is likely that the clinician attending to victims will need to make therapeutic decisions before the results of confirmatory diagnostic tests are available and in situations in which the diagnosis is not known with certainty. In such cases, it is useful to note that many diseases and symptoms caused by chemical and biologic agents will resolve spontaneously, with only supportive care required. Most cases of chlorine or phosgene exposure can be successfully managed by providing meticulous attention to oxygenation and fluid balance. Mustard victims may require intensive multisystem support, but no proven antidote or therapy is available. Many viral diseases, such as smallpox, most viral hemorrhagic fevers, and the equine encephalitides, are also managed supportively.

Ideally, both atropine and pralidoxime should be administered intravenously in severe cases, although the intraosseous route may be acceptable. Some experts recommend that atropine be given intramuscularly in the presence of hypoxia to avoid arrhythmias associated with intravenous administration. Many emergency management services stock military autoinjector kits consisting of atropine and 2-PAM for intramuscular injection. Pediatric atropine autoinjectors are now licensed, although military kits (with 2 mg of atropine and 600 mg of pralidoxime) might be used in children older than 2-3 yr (Table 704-4). Animal studies support the routine prophylactic administration of anticonvulsant doses of benzodiazepines, even in the absence of observable convulsive activity.

The management of vesicant-induced injury is similar to that for burn victims and is largely symptomatic (Chapter 68). Mustard victims will benefit from the application of soothing skin lotions such as calamine and the administration of analgesics. Early intubation of severely exposed patients is warranted to guard against edematous airway compromise. Oxygen and mechanical ventilation may be needed, and meticulous attention to hydration is of paramount importance. Ongoing research suggests a role for oral N-acetylcysteine in mitigating chronic pulmonary effects due to mustard injury. Lewisite victims can be managed in much the same manner as mustard victims. In addition, dimercaprol (British antilewisite [BAL]) in oil, given intramuscularly, may help ameliorate the systemic effects of lewisite.

Baker MD. Antidotes for nerve agent poisoning: should we differentiate children from adults? Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19:211-215.

Bravata DM, Wang E, Holty JE, et al. Pediatric anthrax: implications for bioterrorism preparedness. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2006;141:1-48.

Burklow TR, Yu CE, Madsen JM. Industrial chemicals: weapons of opportunity. Pediatr Ann. 2003;32:230-234.

Cieslak TJ, Henretig FM. Bioterrorism. Pediatr Ann. 2003;32:154-165.

Cieslak TJ, Henretig FM. Ring-a-ring-a-roses: bioterrorism and its peculiar relevance to pediatrics. Curr Op Pediatr. 2003;15:107-111.

Franz DR, Jahrling PB, McClain DJ, et al. Clinical recognition and management of patients exposed to biological warfare agents. Clin Lab Med. 2001;21:435-473.

Hall AH, Dart R, Bogdan G. Sodium thiosulfate or hydroxocobalamin for the empiric treatment of cyanide poisoning? Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:806-813.

Henretig FH, Cieslak TJ, Eitzen EM. Biological and chemical terrorism. J Pediatr. 2002;141:311-326.

Henretig FM, Mechem C, Jew R. Potential use of autoinjector-packaged antidotes for treatment of pediatric nerve agent toxicity. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40:405-408.

Kales SN, Christiani DC. Acute chemical emergencies. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:800-808.

Lee EC. Clinical manifestations of sarin nerve gas exposure. JAMA. 2003;290:659-662.

Markenson D, Redlener I. Pediatric terrorism preparedness national guidelines and recommendations: findings of an evidence-based consensus process. Biosecur Bioterror. 2004;2:301-319.

Markenson D, Reynolds S, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency MedicineTask Force on Terrorism. The pediatrician and disaster preparedness. Pediatrics. 2006;117:340-362.

Migone TS, Subramanian M, Zhong J, et al. Raxibacumab for the treatment of inhalational anthrax. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:135-144.

Montello MJ, Tarosky M, Pincock L, et al. Dosing cards for treatment of children exposed to weapons of mass destruction. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63:944-949.

Patt HA, Feigin RD. Diagnosis and management of suspected cases of bioterrorism: a pediatric perspective. Pediatrics. 2002;109:685-692.

Rotenberg JS, Newmark J. Nerve agent attacks on children: diagnosis and management. Pediatrics. 2003;112:648-658.

Russell D, Blaine PG, Rice P. Clinical management of casualties exposed to lung damaging agents: a critical review. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:421-424.

White SR, Henretig F, Dukes RG. Medical management of vulnerable populations and co-morbid conditions of victims of bioterrorism. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2002;20:365-392.