CHAPTER 244 Benign Tumors of the Peripheral Nerve

History

From the time of Hippocrates through the 18th century, the common belief was that an injured nerve could not be repaired and that manipulation of an injured nerve could lead to pain, convulsions, or even death. Most reports of nerve tumors in the 17th century concerned the swellings found at the ends of transected nerves. Odier of Geneva coined the term neuroma for enlargement of peripheral nerves.1 The first recognizable description of what was probably a peripheral nerve sheath tumor was reported by Cheselden in 1741. In the text of The Anatomy of the Human Body, Cheselden described a tumor that occupied the center of the “cubital” nerve, displacing the nerve fibers to the periphery.2 Wood, in his extensive 1829 review of nerve tumors, noted that “a number of nervous fasciculi, sometimes a good deal flattened, can be traced in a perfect state of continuity running over the surface to be connected below to the trunk of the nerve.”3 Although it appears obvious today that the tumor can be removed sparing the nerve’s fascicles, the dogma of the day was that it was dangerous to manipulate a peripheral nerve. In 1800, Hunter performed an en bloc resection of a length of a patient’s musculocutaneous nerve containing a tumor. His assistant, Home, took the specimen to the laboratory and was able to dissect the nerve fascicles from the tumor. Home went on to enucleate a tumor from the axillary nerve preserving the underlying fascicles.4 Unfortunately, the patient died on the seventh postoperative day, and an autopsy failed to reveal a cause of death. Subsequently, both Swan and Wood discouraged dissecting tumors from nerves, speculating that the inflammation of the nerve led to Home’s patient’s death.3,5

In the Lancet, Mr. James Syme reported treating a 43-year-old farm laborer who had “a swelling of the forearm on the palmer side, a little above the wrist about as large as a hen’s egg.”6 Mr. Syme assessed the patient as having a neuroma of the median nerve and wrote, “I think before resorting to removal of the hand, an attempt should be made to dissect out the tumor, but the chances of success in accomplishing this being very small.” At the time of operation, he found the tumor intimately connected to the nerve and amputated the hand. On examining the specimen, he found “the tumor itself was of roundish form, of yellow-white color, and pretty firm consistency. The fibers of the nerve were beautifully expanded over its surface.”

Through the early 1800s, there was confusion in distinguishing between traumatic neuromas and nerve tumors. In 1849, R. W. Smith articulated the difference among traumatic, saltatory, and multiple neuromas.7 Nevertheless, Smith continued to advocate en bloc resection over enucleation for fear of causing inflammation of the nerve and death of the patient. Virchow divided peripheral nerve tumors into true tumors, which contained both nerve fibers and elements of the nerve sheath, and fake tumors, which contained only the elements of the nerve sheath.8 By the mid-1800s, surgeons became interested in reestablishing nerve continuity. As noted by Walker, Michon in 1889 and Nelaton in 1863 described management of the sciatic and median nerves, respectively, with en bloc resection followed by reapproximation of the nerve ends.9 Amputation as a primary treatment for peripheral nerve tumors became increasingly less popular, and in 1887, Krause advocated simple excision for well-encapsulated nerve tumors, reserving amputation for recurrent nerve tumors.10

Introduction

Peripheral neural sheath tumors (PNSTs) originate and grow within the nerve.11,12 PNSTs include the schwannoma and neurofibroma, whose differentiation has been clarified using electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry. These same techniques have resulted in a wide acceptance that the principle cell of origin of these tumors is the Schwann cell.13 Benign peripheral non–neural sheath tumors (PNNSTs) can behave aggressively and include ganglions, lipomas, desmoids, ganglioneuromas, hemangiomas, myoblastomas or granular cell tumors, lymphangiomas, and the rare hemangioblastoma or meningioma.

Benign Tumors of Neural Sheath Origin

Schwannoma

Schwannomas are the most common benign tumor of peripheral nerves, yet they account for fewer than 8% of all soft tissue tumors.14 The incidence of benign schwannomas involving peripheral nerve tends to be higher in females than in males. These tumors can occur in patients with NF1; however, neurofibromas are much more common in this population.15

A benign schwannoma of peripheral nerve characteristically presents as a painless, eccentric, oval mass present for some time in a deep location in the course of a nerve or plexal element.16 On palpation, it can be moved laterally, but not longitudinally in the direction that the tumor runs. Percussion over the mass may produce Tinel’s sign, that is, paresthesias in the distribution of the involved nerve.17

Because the growth of peripheral nerve schwannomas usually occurs over many years, large lesions slowly stretch and elongate the fascicles.18,19 Thus, neurological function tends to be intact in these tumors. Loss of function from smaller benign schwannomas is also rare unless a prior biopsy had injured the involved nerve or an unsuccessful attempt at tumor removal had been performed. Under these circumstances, the residual mass may be quite painful, motor loss in the distribution of the involved nerve can be severe, and sensation is markedly impaired or absent. A six-point grade system, based on the level of contraction or movement that can be attained in the affected limb, is used to evaluate the symptoms of neural peripheral nerve tumors (Table 244-1).

TABLE 244-1 Louisiana State University Medical Center Criteria for Grading Muscle Function After Tumor

| GRADE | EVALUATION | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Absent | No muscle contraction, absent sensation |

| 1 | Poor | Proximal muscles contract but not against gravity; sensory grade 1 or 0 |

| 2 | Fair | Proximal muscles contract against gravity; distal muscles do not contract; sensory grade, if applicable, is usually 2 or lower |

| 3 | Moderate | Proximal muscles contract against gravity and some resistance; some distal muscles contract against at least gravity; sensory grade is usually 3 |

| 4 | Good | All proximal and some distal muscles contract against gravity and some resistance; sensory grade is 3 or better |

| 5 | Excellent | All muscles contract against moderate resistance; sensory grade is 4 or better |

Adapted from Kim DH, Midha R, Murovic J, et al: Kline & Hudsons Nerve Injuries. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008.

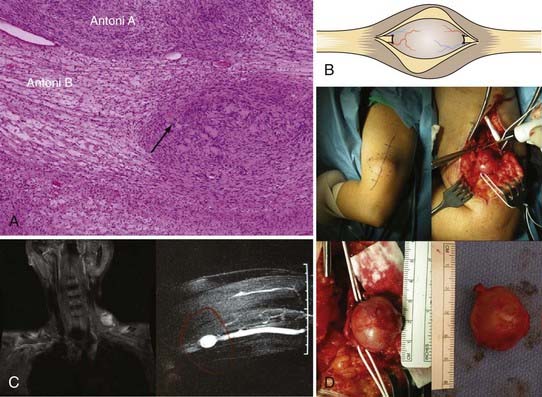

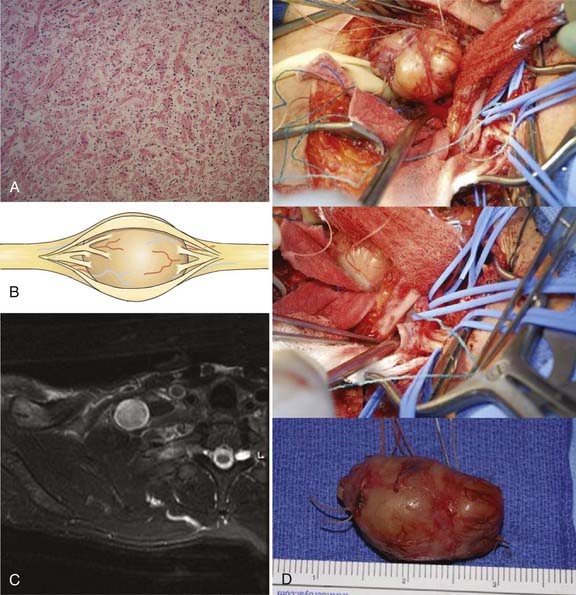

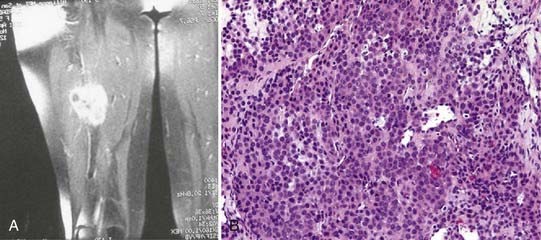

The cell of origin of the schwannoma is the Schwann cell, which has a basement lamella and is more differentiated than, for example, the perineurial fibroblast. The cells of the tumor are arranged in varying proportions of arrays of cells called Antoni type A and Antoni type B tissues. The Antoni type A tissue of the schwannoma is very cellular with a compact array of spindle-shaped cells. Some of these cells may palisade to form Verocay bodies. The Antoni type B pattern seen in some schwannomas, on the other hand, is less compact and has a loose-textured matrix (Fig. 244-1A). When schwannoma tissue is stained with Alcian blue, a mucopolysaccharide stain, or with reticular stains, the results are less positive than those seen with a neurofibroma. In neurofibromas, connective tissue fibers, especially collagen, are conspicuous elements. In addition, nerve fibers within a neurofibroma are more numerous and more obvious under the microscope than in a schwannoma.

Surgical Approach

The removal of a schwannoma is straightforward; however, serious complications can occur if care is not taken with the dissection and preservation of involved plexal elements or nerves.20–22 Exposure of the nerve of origin well proximal and distal to the lesion is necessary. Other nerves or plexal elements and vessels are dissected away and spared. An area in the circumference of the capsule with few or no fascicles is then opened in a longitudinal fashion. The encapsulated tumor spreads or “baskets” the nerve fascicles apart, displacing them to its periphery.23 These fascicles may be adherent to the outer capsular surface of the tumor, although they are seldom incorporated into the capsule.24

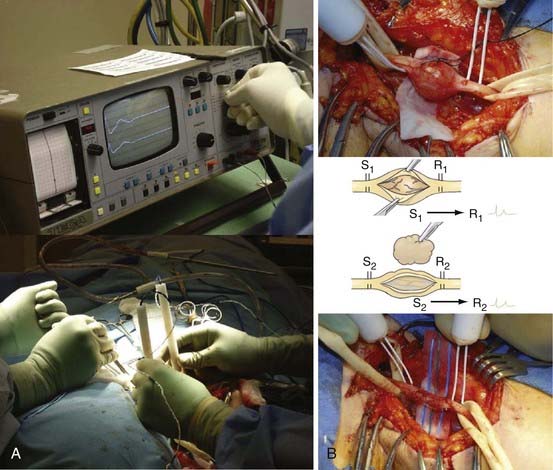

One or sometimes two small fascicles are seen entering and leaving the tumor, and these are exposed and encircled with vasoloops (Fig. 244-1B to D). Stimulation and recording across the fascicles entering and the fascicles leaving each pole of the encapsulated tumor are then performed (Fig. 244-2A and B). Stimulation of the entering fascicles usually does not produce distal muscle function, nor do these fascicles conduct a nerve action potential (NAP) through the tumor to distal elements or nerves. These mostly nonfunctional proximal or distal fascicles are sectioned, and the tumor is removed as a single mass. One way to do this is to section one nonfunctional entering or leaving fascicle, lift the tumor at that pole, and dissect it away from underlying and laterally reflected but retained fascicles. The opposite pole’s nonfunctional fascicle is then sectioned to complete the removal.

An alternative approach sometimes used on large tumors is to open the capsule longitudinally and enucleate the homogenous or sometimes cystic tumoral contents using suction, forceps and scissors, or a Cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator (CUSA).25,26 The spared fascicles are teased away from the tumor capsule, which is then resected. The capsule is totally removed to reduce the chance of recurrence, although some surgeons disagree with this concept and leave the capsule.

Some schwannomas become quite large and extend beyond the immediate region of the nerve. These lesions are more difficult to remove, which increases the possibility of recurrence from the remaining tumor or capsule.27

Surgical Outcome

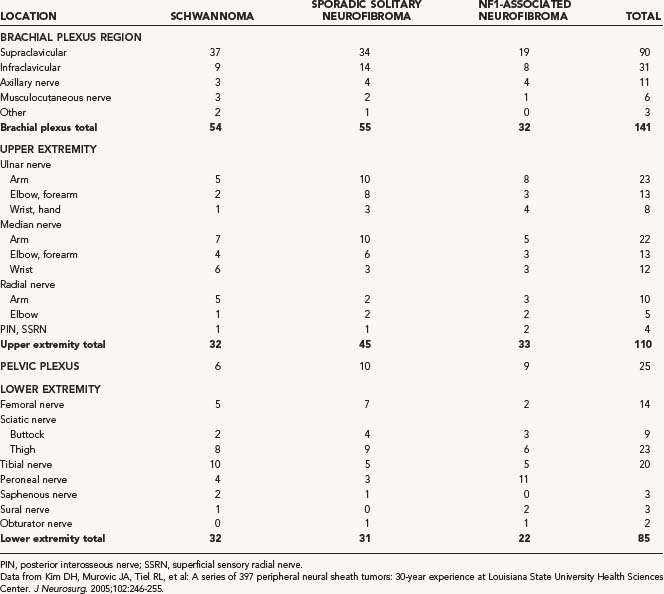

In the recent review of our 30 years of experience treating neural sheath tumors, we found that schwannomas were less common than neurofibromas in both the brachial plexus and the pelvic plexus and that most schwannomas of the brachial plexus region were located supraclavicularly. See Table 244-2 for a summary of this case review.28

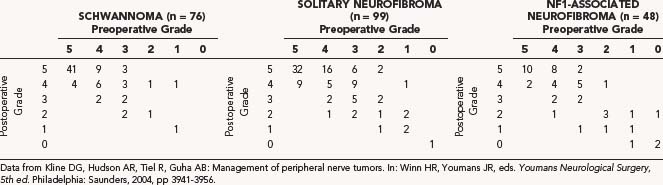

We also found that in a representative sample of 76 patients with schwannomas, baseline function was preserved or improved 89% of the time.28 The preoperative and postoperative grades (0 to 6) were compared to determine the effectiveness of surgical treatment (Table 244-3).29

Neurofibroma

There are two groups of neurofibromas. The first group includes the solitary tumor or non-NF1 neurofibroma, which is unassociated with other such tumors.30 This tumor is most likely to be fusiform in appearance.31 The second group of neurofibromas, the plexiform neurofibromas, are seen almost exclusively in conjunction with NF1. Plexiform neurofibromas exhibit multiple nodular growths along a long segment of a major nerve trunk, and these growths extend into the nerve branches. They result in the “bag of worms” appearance on gross inspection and cross-sectional imaging. Fusiform lesions are, however, more likely to be seen in patients with NF1 than are plexiform neurofibromas.

Neurofibromas are intraneural masses, which are more likely to be more painful than schwannomas. Percussion over a neurofibroma usually produces a dramatic Tinel sign.32 Like schwannomas, these tumors, along with their nerve of origin, can be displaced from side to side, but not longitudinally. Pain can become a very severe problem if there has been prior biopsy or attempted removal.33

NF1-associated neurofibromas are found in patients with other stigmata of that disease including café au lait spots, multiple small spots of skin discoloration, skin tags or smaller subcutaneous tumors, Lisch nodules of the iris, and central nervous system tumors such as acoustic neurilemoma or tumors arising from the nerve roots of the spine.34

The neurofibroma has a myxomatous matrix and exhibits a prominent mucopolysaccharide staining (Fig. 244-3A). The intense reticulum staining of the neurofibroma is due to the numerous collagen fibrils in its myxocollagenous background, whereas the schwannoma has a paucity of these collagen fibrils and, hence, stains poorly.

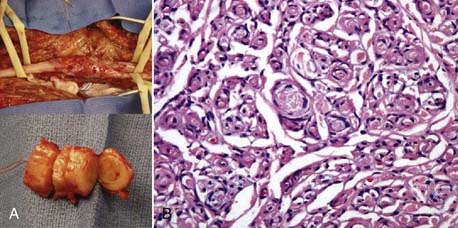

Surgical Approach

The neurofibroma usually has two or more entering and exiting fascicles, which are larger than those seen in a schwannoma, and a capsule that is more adherent to the central mass of the tumor than that of a schwannoma (Fig. 244-3B). A large neurofibroma can sometimes be approached from above the inferiorly located fascicles or below fascicles located superiorly at the tumor’s proximal or distal ends. The entering or exiting fascicles are then dissected free, sectioned, and used to elevate the tumor. This maneuver allows the dissection of fascicular structures away from the tumor, beginning at one end until the opposite pole is reached.

Fascicles entering and exiting the tumor are tested by stimulating the proximal fascicles and recording NAPs from the distal ones. As with the schwannoma, if traces are flat, the entering and exiting fascicles can be sacrificed, and the tumor can be removed as a solitary mass (Fig. 244-3C and D). If NAPs are positive across these fascicles, the fascicles need to be traced into and out of the tumor and spared. At times, even these fascicles need to be sacrificed to achieve resection of the tumor. In these cases, fascicular defects can be replaced by grafts or, on occasion, partial fascicular graft repairs. Even a large fusiform lesion can be associated with multiple smaller neurofibromas or neurofibromatous change in nerve both above and below the lesion, necessitating similar graft repair.

Surgical Outcome

Most of the benign tumors of the brachial plexus treated by us in a 30-year period at LSUHSC were neurofibromas (62%); 63% of these were sporadic solitary neurofibromas, and 37% were neurofibromas removed from patients with NF1. The tumors associated with NF1 were completely removed in 56% of cases and partially resected in 44%. See Table 244-2 for a complete listing of the results of this series.

In the LSUHSC review, the NF1-associated neurofibromas were excised in most cases without producing a serious deficit even when they involved a major nerve. Owing to the more difficult dissection of neurofibromas in patients with NF1, resolution of symptoms was often not as good as that in patients without NF1. Nonetheless, in patients with NF1 in whom neurofibromas were resected, 83% had stable or improved motor function. Because neurofibromas in patients with NF1 are more likely to be plexiform, the incidence of total resection was 76%, compared with all tumors in patients harboring solitary neurofibromas.28

A series of 99 solitary neurofibromas and 48 NF1-associated neurofibromas was studied by comparing the symptomatic grade before and after surgical treatment. See Table 244-3 for a summary of the results of this case series.29

Surgical treatment of plexiform neurofibromas (Fig. 244-4A) tends to be difficult, but it is possible when there are good indications such as symptomatic tumors involving sensory nerves or branches. In our experience, complete removal generally was not possible without a loss of neurological function. In some cases, even subtotal removal of a plexiform tumor led to some loss of function. Nerve sections proximal and distal to the lesion, followed by repair of the often lengthy gap, did not usually restore function. For large tumors or in cases in which severe pain was a dominant symptom, decompression with removal of a portion of the tumor bulk provided benefit (Fig. 244-4B). In selected cases, it was possible to reduce pain by decompressing the nerve involved by the tumor by neurolysis, especially if the nerve was in a closely confined area such as behind the elbow or knee or in the carpal tunnel or Guyon’s canal. Tumors involving less important sensory nerves or branches, such as the antebrachial cutaneous, superficial sensory radial, sural, or saphenous nerves, could be totally removed along with the nerve of origin.

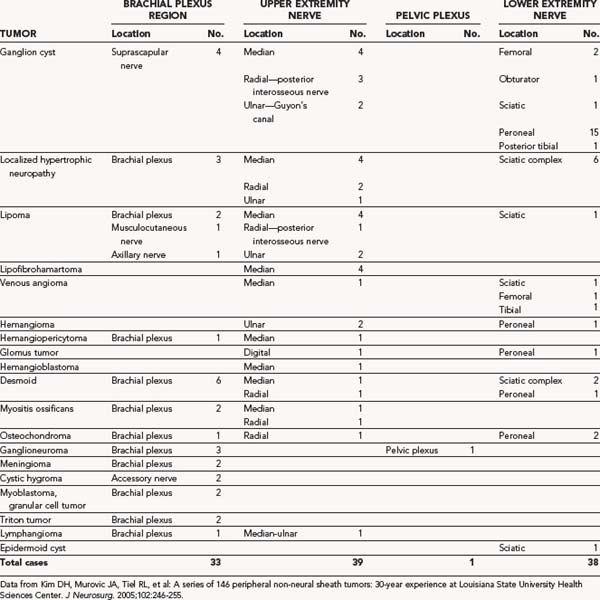

Benign Tumors of Non–Neural Sheath Origin

Benign PNNSTs secondarily involve nerve and tend to produce symptoms because of nerve compression rather than actual origination in nerve.35–37 There are exceptions, however, and these include the desmoids, myoblastomas, lymphangiomas, and the rare extraspinal meningioma, all of which can be quite adherent to epineurium and difficult to remove, with a high incidence of recurrence.38 Some ganglions are extraneural and can compress nerve, whereas others either dissect down to or originate at an intraneural level. As a result, removal of these lesions can be either incomplete or accompanied by a deficit. Hemangiomas or hemangiopericytomas can envelop nerve or elements of the brachial plexus, but the extremely rare hemangioblastoma can arise in nerve, as can rare tumors of congenital origin such as a triton tumor of the plexus. The benign PNNSTs are summarized in Table 244-4.

Desmoid Tumors

Desmoid tumors involving nerve or plexus can occur but are infrequent. Although desmoids are benign, they tend to be invasive of soft tissues, and if close to nerve, they can envelop and adhere to the nerve and other structures connected to muscle (Fig. 244-5).39 Although the most frequent site of origin is the abdominal musculature, desmoids can originate in the neck, shoulder, and upper and lower extremities.

Desmoid tumors have poorly delineated surgical margins.40 Despite what would appear to be gross total excision, recurrence is common, especially if wide resection is difficult because of contiguous important neural or vascular structures. In our experience, tumors in the region of the plexus have been difficult to completely eliminate and have tended to recur. Despite this, most cases of recurrence have been successfully resected.

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice for these tumors. Gross total excision with microscopically negative margins has been reported to produce recurrence rates of 5% to 50%, whereas those procedures demonstrating positive microscopic margins produce recurrence rates as high as 90%.40–45 Radiation therapy may control low-grade growth, and external-beam radiation (55 Gy) improves local control in patients with positive margins.40,45–47 Unfortunately, some series have shown a significant injury to the brachial plexus in patients receiving as little as 40 Gy to tumors in this region.40,48 Tamoxifen has been used as a chemotherapeutic adjunct to surgery mainly in locations other than the peripheral nerve for desmoids with variable results40,49–52 and has also resulted in late recurrences.40,53,54 Cytotoxic therapy with vincristine, actinomycin D, and cyclophosphamide is known to have an effect and corticosteroids have been rarely shown to cause tumor regression.40

This lesion has its origin in the mesenchyma and usually arises in muscle or fascial structures connected to the muscle. Most of the desmoid tumors removed at LSUHSC (55%) involved the brachial plexus. This number represents 18% of brachial plexus region tumors. See Table 244-4 for a description of desmoid tumors studied in this series.

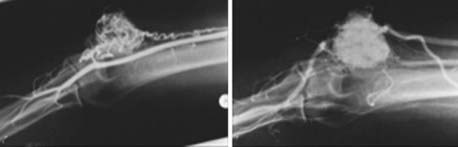

Osteochondroma

In the LSUHSC review, four osteochondromas were reported.28 In the lower extremity, two of these tumors (5% of the 38 lower extremity lesions) were removed from the peroneal nerve. One patient had a large osteochondroma arising in the paraspinal region and extending to the brachial plexus. This lesion had arisen spontaneously and was associated with a thoracic outlet syndrome. A posterior subscapular approach was used for resection of both the tumor and the posterior portion of the rib, followed by neurolysis of the brachial plexus. In the upper extremity, one tumor involved the humerus, resulting in a severe radial distribution deficit preoperatively. After removal of the tumor and neurolysis of the radial nerve, the patient slowly regained function over a 2-year period.

Myositis Ossificans

There were four cases of myositis ossificans reported in the LSUHSC review (see Table 244-4).28 One patient with an ossified mass involving the brachial plexus underwent partial resection of a large area of axillary fibromyositis and a repeated operation for resection of residual tumor. The tumor involving the radial nerve, which appeared after the patient suffered a contusion to the lateral portion of the upper arm, presented as a large calcified mass and was removed. It had originated in the triceps muscle, had compressed the nerve as it came around the humerus in the radial groove, and was adherent to the nerve, although it had not invaded it.

Ganglion Cysts

Most ganglion cysts arise near joints. These are thought to occur at the site of a small tear in the ligament overlying a tendon sheath or joint capsule. Ganglion cysts tend to be present in areas that do not involve nerves, such as the dorsum of the hand or wrist.37

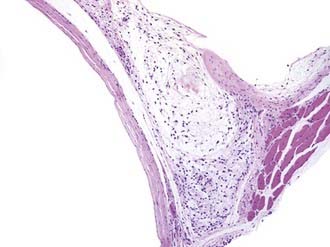

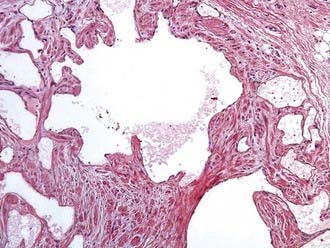

The cysts contain a mucoid material. The cyst wall of ganglion cysts is composed of compressed collagen fibers and occasional flattened cells. There is an associated mucoid degeneration of the surrounding fibrous tissue (Fig. 244-6). There is an absence of inflammatory cells, a lack of mitotic activity, and no synovial or epithelial lining of the single or multiloculated cysts.

A ganglion cyst involving the peripheral nerve is thought to arise from the adjacent synovial joint and then to track back along a small articular nerve branch to reach its final position within a major nerve trunk.55 More difficult to explain in terms of origin are ganglion cysts at the suprascapular notch, which compress the suprascapular nerve. In our experience, the ganglion cysts in this region did not appear to arise from the shoulder joint.

In our experience, most ganglion cysts (61%) arose from the lower extremity, whereas 12% occurred in the brachial plexus region.28 For a summary of ganglion cysts, see Table 244-4.

Myoblastoma or Granular Cell Tumor

These tumors consist of a mixture of plump, angular cells with cytoplasm containing eosinophilic granules, which represent a large number of lysosomes.56 The cells have small, regular, hyperchromatic nuclei, and mitotic figures are few in number. Cells tend to be rather compactly arranged. This tumor tends to spread as a sheet of tumorous tissue. Groups of lymphoid cells occur at the periphery of most lesions.

Lymphangiomas

When lymphangiomas involve nerve, they have many of the same characteristics as myoblastomas.58 The cells tend to spread as a sheet of tumorous tissue that envelops other structures, rather than forming a true mass lesion.

Lymphangiomas are focal proliferations of well-differentiated lymphatic tissue that present as multicystic accumulations (Fig. 244-7). They are subdivided into three categories. Capillary lymphangiomas are thin-walled lymphatic channels that occur as small, well-circumscribed cutaneous lesions. Cavernous lymphangiomas are also thin-walled lymphatic channels, but these tumors have an associated stroma. Cystic lymphangioma, the third category, has large, well-circumscribed, multiloculated cystic spaces lined by endothelium that contain a significant connective tissue component. Cavernous and cystic lymphangiomas can coexist within the same lesion. The surgical excision for these tumors is the same as that described for the myoblastoma.

FIGURE 244-7 Pathology slide of a lymphangioma. This lesion has multicystic accumulations of well-differentiated lymphoid tissue.

Of the two lymphangiomas shown in Table 244-4, one in an upper extremity involved the medial portion of the upper arm, enveloped the proximal median and ulnar nerves, and these nerves required neurolysis. The other tumor was continuous with brachial plexus elements. This lesion was approached by a posterior subscapular approach. The first rib was resected, and the tumor was successfully removed from the C7, C8, and T1 spinal nerves as well as from the middle and lower trunks of the brachial plexus.

Lipomas

There are four lipomatous conditions that can affect nerve: a solitary lipoma; a “macrodystrophia lipomatosa,” which produces an overgrowth of the hand or fingers and can cause neural compression; an encapsulated lipoma; and a lipofibromatous hamartoma. The latter two lipomas can both have growth that begins within the nerve.37 Lipomas have a fine capsule and are composed entirely of adipose tissue. Lipohamartomas present as a significant fatty, fibrous mass within nerve.

In our series, 12 lipomas found to compress a nerve were removed from various locations (see Table 244-4).

Tumors of Vascular Origin

Arteriovenous Fistulas or Malformations

There were 12 tumors of vascular origin in our recent series. Subgroups of these 12 vascular tumors included 4 venous angiomas, 3 hemangiomas, 2 hemangiopericytomas, 2 glomus tumors, and 1 hemangioblastoma. For a complete description of the locations of these tumors, see Table 244-4.

Hemangioblastomas

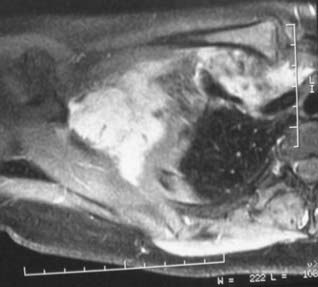

Hemangioblastomas are much more common in the central than in the peripheral nervous system. The recent literature has reports of only two peripheral nerve hemangioblastomas, one of the sciatic nerve at midthigh level59 and one of the radial nerve (Fig. 244-9).60

Glomus Tumors

These unusual tumors are thought to arise from glomeruli in which a small arteriole connects to an adjacent vein by way of a tiny canalicular system.61 These microscopic structures may relate to local changes in blood flow, perfusion pressure, and regulation of heat exchange.

Glomus tumor histology shows endothelium-lined vascular spaces surrounded by clusters of so-called glomus cells in a canaliculus-like arrangement (Fig. 244-10A and B). Glomus cells are monomorphous round or polygonal cells with plump nuclei and scant eosinophilic cytoplasm.

In our experience, glomus tumors generally require wide local excision to minimize recurrence.

Localized Hypertrophic Neuropathy (Onion Whorl Disease)

This uncommon disorder results in thickening of a peripheral nerve. Localized hypertrophic neuropathy (LHN) of a peripheral nerve results from hyperplasia of Schwann cells or, more likely, perineurial cells, leading to fascicular enlargement. There is a moderate length of localized cylindrical or fusiform swelling in the course of one and sometimes two major peripheral nerves in a limb (Fig. 244-11A). The lesion does not spread to other nerves or to other sites in the body. Unfortunately, loss in the distribution of a nerve involved by this disease is usually progressive. LHN can affect children or adults.

Johnson and Kline62 observed the perifascicular perineurium of LHN, as now defined, to be defective, attenuated, fibrotic, or hyalinized owing to a postulated damage to perineurium with breakdown of the perfusion barrier as the primary event in the lesion’s pathogenesis. Gruen and associates,63 in a relatively large series of cases, however, found no history of significant trauma for most LHN cases or, for that matter, in those previously reported in the literature. They proposed that the pathophysiologic proliferative response in LHN may be a reaction to an unknown chemical, toxic, or compressive mechanical injury or a neoplastic process.

Histologically, there is a striking proliferation of perineurial cells in a whorl formation (leading to the term onion whorl disease) surrounding each individual axon with marked endoneurial fibrosis and also fibrotic replacement of the perineurium (Fig. 244-11B). Myelin is either lost or greatly diminished in thickness. Compartmentation, in which the axon is surrounded by fibrous tissue and also appears to be encircled by its own perineurium, is also characteristic. This produces hypertrophic fascicles.

Intraneural tumors and other nontumorous and nontraumatic causes of nerve enlargement should be in the differential diagnosis.64–66 They include amyloidosis, Hansen’s disease, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, and Dejerine-Sottas disease.67,68

In the recent case review, 16 LHN lesions were removed, 6 from the sciatic complex, 7 from the upper extremity, and 3 from the brachial plexus (see Table 244-4).

Radiation-Induced Brachial Plexus Lesions (Actinic Plexitis)

Determining the nature of these lesions is a common dilemma in patients with new functional loss in the muscles innervated by the involved plexus elements or peripheral nerve. For example, in a patient who has undergone prior mastectomy for removal of primary breast carcinoma, a lesion in the brachial plexus causing functional loss may be due to radiation fibrosis, recurrent carcinoma with invasion of the plexus, or both.69 The following features can be used to distinguish between recurrent carcinoma and irradiation plexitis.

Several criteria suggest carcinomatous compression or invasion, including (1) rapid progression of motor or sensory loss in the distribution of specific plexus elements, especially lower trunk, medial cord, or its outflows, accompanied by severe pain in the distribution of specific plexus elements; (2) onset in the months to early years after the original diagnosis of breast cancer, with some exceptions; (3) a localized mass seen on computed tomography (CT) or MRI; (4) evidence of metastasis elsewhere in the body; (5) neoplastic tissue obtained by needle biopsy; and (6) no fasciculations or myokymia on electromyography. Unfortunately, in a few cases, we have seen intraneural breast carcinoma occur in the plexus many years after the patient was thought to be cured. Less definite but also suggestive of carcinoma are severe pain, especially in the distribution of specific plexus elements, and absence of lymphedema.70

Features favoring irradiation plexitis include (1) the slow progression of motor or sensory loss accompanied by pain with paresthesias, often the dominant symptom; (2) onset tending to occur years after the diagnosis of breast cancer; (3) neuroimaging showing plexal thickening, without a discrete mass; (4) no evidence of metastasis elsewhere in the body; (5) no neoplastic tissue and a marked degree of scarring seen on the histology obtained from needle biopsy; and (6) electromyography showing fasciculations or myokymia.71 Unfortunately, we have also seen the onset of irradiation plexitis symptoms within only a few months of completion of radiation therapy in a few cases. Thus, the time of onset of radiation plexitis is quite variable and can begin as early as 6 months or as long as 18 to 20 years after the course of radiation therapy.

Other criteria favoring carcinoma involving the brachial plexus, rather than radiation fibrosis includes (1) a history of a radiation dose less than 6000 cGy, and (2) the presence of Horner’s syndrome.71 Cases of irradiation plexitis without carcinoma may present, however, with one or more of these latter features.39

The posterior approach is used to operate on the brachial plexus,72 specifically for tumor involvement of (1) spinal nerves at an intraforaminal level; (2) C7, C8, and T1 roots; (3) the lower brachial plexus trunk; or (4) if the patient has undergone tumor resection or radiation therapy with consequent substantial scarring anterior to the plexus. The posterior subscapular approach is also useful in exposing both the intraforminal and extraforaminal parts of the dumbbell-shaped neural sheath tumors, most of which are neurofibromas.

Campbell R. Tumors of peripheral and sympathetic nerves. In Youmans J, editor: Neurologic Surgery, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Saunders, 1990.

Cutler EC, Gross R. Neurofibroma and neurofibrosarcoma of peripheral nerves. Arch Surg. 1936;33:733-779.

Das Gupta TK, Brasfield RD, Strong EW, et al. Benign solitary schwannomas (neurilemomas). Cancer. 1969;24:355-366.

de los Reyes RA, Chason JL, Rogers JS, et al. Hypertrophic neurofibrosis with onion bulb formation in an isolated element of the brachial plexus. Neurosurgery. 1981;8:397-399.

deSouza FM, Smith PE, Molony TJ. Management of brachial plexus tumors. J Otolaryngol. 1979;8:537-540.

Donner TR, Voorhies RM, Kline DG. Neural sheath tumors of major nerves. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:362-373.

Dubuisson AS, Kline DG, Weinshel SS. Posterior subscapular approach to the brachial plexus: Report of 102 patients. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:319-330.

Gaposchkin CG, Bilsky MH, Ginsberg R, et al. Function-sparing surgery for desmoid tumors and other low-grade fibrosarcomas involving the brachial plexus. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:1297-1301.

Giannini C, Scheithauer BW, Hellbusch LC, et al. Peripheral nerve hemangioblastoma. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:999-1004.

Godwin JT. Encapsulated neurilemoma (schwannoma) of the brachial plexus: report of eleven cases. Cancer. 1952;5:708-720.

Gruen JP, Mitchell W, Kline DG. Resection and graft repair for localized hypertrophic neuropathy. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:78-83.

Gunderson LL, Nagorney DM, McIlrath DC, et al. External beam and intraoperative electron irradiation for locally advanced soft tissue sarcomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;25:647-656.

Johnson PC, Kline DG. Localized hypertrophic neuropathy: possible focal perineurial barrier defect. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 1989;77:514-518.

Karakousis CP, Mayordomo J, Zografos GC, et al. Desmoid tumors of the trunk and extremity. Cancer. 1993;72:1637-1641.

Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, et al. A series of 146 peripheral non-neural sheath tumors:30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:246-255.

Kline DG, Hudson AR, Tiel R, Guha AB. Management of peripheral nerve tumors. In: Winn HR, Youmans JR, editors. Youmans Neurological Surgery. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:3941-3956.

Lederman RJ, Wilbourn AJ. Brachial plexopathy: recurrent cancer or radiation? Neurology. 1984;34:1331-1335.

Smith R, Lipke R. Surgical treatment of peripheral nerve tumors of the upper limb. In: Omer G, Spinner M, editors. Management of Peripheral Nerve Lesions. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1980.

Thomas JE, Colby MYJr. Radiation-induced or metastatic brachial plexopathy? A diagnostic dilemma. JAMA. 1972;222:1392-1395.

1 Odier L. Manuel de Medecine Pratique, 2nd ed. Paris: J. Paschoud; 1811.

2 Cheselden W. The Anatomy of the Human Body, 6th ed. London: William Bowyer; 1741.

3 Wood W. Observation on Neuroma. Trans Med-Chir Soc Edin. 1829;3:367-433.

4 Home E. An account of an uncommon tumor formed in one of the axillary nerves. Tr Soc Impr M Chir Knowl. 1800;2:152-163.

5 Swan J. A Dissertation on the Treatment of Morbid Local Affections of Nerves. London: J Drury; 1820.

6 Syme J. Lectures on clinical surgery. Lecture XXII. Neuromata. Lancet. 1855;1:551-553.

7 Smith RW. A Treatise on the Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment of Neuroma. Dublin: Hodges and Smith; 1849.

8 Virchow R. Die Krankhaften Geschwulste. Berlin: A Hirschwald; 1864.

9 Walker AE. A History of Neurological Surgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1951.

10 Krause F. Uber maligne Neurome und das Vorkommen von Nervenfasern in denselben. Leopzig: Breitkopf & Hartel; 1887.

11 Das Gupta TK. Tumors of the peripheral nerves. Clin Neurosurg. 1978;25:574-590.

12 Thomas JE, Piepgras DG, Scheithauer B, et al. Neurogenic tumors of the sciatic nerve. A clinicopathologic study of 35 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1983;58:640-647.

13 Russell DS, Rubenstein LJ. Pathology of Tumours of the Nervous System, 6th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

14 Rockwell GM, Thoma A, Salama S. Schwannoma of the hand and wrist. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:1227-1232.

15 Das Gupta TK, Brasfield RD, Strong EW, et al. Benign solitary schwannomas (neurilemomas). Cancer. 1969;24:355-366.

16 Byrne JJ, Cahill JM. Tumors of major peripheral nerves. Am J Surg. 1961;102:724-727.

17 Cravioto H. Neoplasms of peripheral nerves. In: Wilkins R, Rengachary E, editors. Neurosurgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1988.

18 Dodge HWJr, Craig WM. Benign tumors of peripheral nerves and their masquerade. Minn Med. 1957;40:294-301.

19 Fisher RG, Tate HB. Isolated neurilemomas of the brachial plexus. J Neurosurg. 1970;32:463-467.

20 Donner TR, Voorhies RM, Kline DG. Neural sheath tumors of major nerves. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:362-373.

21 Rizzoli H, Horowitz N. Peripheral nerve tumors. In: Horowitz N, Rizzoli H, editors. Postoperative Complications of Extracranial Neurological Surgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1987.

22 Rosenberg AE, Dick HM, Botte MJ. Benign and malignant tumors of peripheral nerve. In: Gelberman R, editor. Operative Nerve Repair and Reconstruction. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1991.

23 Whitaker WG, Droulias C. Benign encapsulated neurilemoma: a report of 76 cases. Am Surg. 1976;42:675-678.

24 Godwin JT. Encapsulated neurilemoma (schwannoma) of the brachial plexus; report of eleven cases. Cancer. 1952;5:708-720.

25 Campbell R. Tumors of peripheral and sympathetic nerves. In Youmans J, editor: Neurologic Surgery, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Saunders, 1990.

26 Ott W. The surgical treatment of solitary tumors of the peripheral nerves. Texas State J Med. 1924;20:171-175.

27 Gyhra A, Israel J, Santander C, et al. Schwannoma of the brachial plexus with intrathoracic extension. Thorax. 1980;35:703-704.

28 Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, et al. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:246-255.

29 Kline DG, Hudson AR, Tiel R, Guha AB. Management of peripheral nerve tumors. In: Winn HR, Youmans JR, editors. Youmans Neurological Surgery. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:3941-3956.

30 Cutler EC, Gross R. Neurofibroma and neurofibrosarcoma of peripheral nerves. Arch Surg. 1936;33:733-779.

31 DaSilva AL, deSouza RP. Neurofibroma solitario do plexobraquial. Hospital (Rio). 1964;65:853-859.

32 Dart LHJr, MacCarty CS, Love JG, et al. Neoplasms of the brachial plexus. Minn Med. 1970;53:959-964.

33 deSouza FM, Smith PE, Molony TJ. Management of brachial plexus tumors. J Otolaryngol. 1979;8:537-540.

34 Seinfeld J, Kleinschmidt-Demasters BK, Tayal S, Lillehei KO. Desmoid-type fibromatoses involving the brachial plexus: treatment options and assessment of c-KIT mutational status. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:749-756.

35 Byrne JJ. Nerve tumors. In: Gelberman R, editor. Operative Nerve Repair and Reconstruction. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1991.

36 Posch J. Soft tissue tumors of the hand. In: Jupiter J, editor. Flynn’s Hand Surgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1991.

37 Smith R, Lipke R. Surgical treatment of peripheral nerve tumors of the upper limb. In: Omer G, Spinner M, editors. Management of Peripheral Nerve Lesions. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1980.

38 Woodruff JM. The pathology and treatment of peripheral nerve tumors and tumor-like conditions. CA Cancer J Clin. 1993;43:290-308.

39 Lusk MD, Kline DG, Garcia CA. Tumors of the brachial plexus. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:439-453.

40 Gaposchkin CG, Bilsky MH, Ginsberg R, et al. Function-sparing surgery for desmoid tumors and other low-grade fibrosarcomas involving the brachial plexus. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:1297-1301.

41 Acker JC, Bossen EH, Halperin EC. The management of desmoid tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;26:851-858.

42 Brodsky JT, Gordon MS, Hajdu SI, et al. Desmoid tumors of the chest wall. A locally recurrent problem. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;104:900-903.

43 Faulkner LB, Hajdu SI, Kher U, et al. Pediatric desmoid tumor: retrospective analysis of 63 cases. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2813-2818.

44 Karakousis CP, Mayordomo J, Zografos GC, et al. Desmoid tumors of the trunk and extremity. Cancer. 1993;72:1637-1641.

45 Plukker JT, van Oort I, Vermey A, et al. Aggressive fibromatosis (non-familial desmoid tumour): therapeutic problems and the role of adjuvant radiotherapy. Br J Surg. 1995;82:510-514.

46 Gunderson LL, Nagorney DM, McIlrath DC, et al. External beam and intraoperative electron irradiation for locally advanced soft tissue sarcomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;25:647-656.

47 Leibel SA, Wara WM, Hill DR, et al. Desmoid tumors: local control and patterns of relapse following radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1983;9:1167-1171.

48 Mondrup K, Olsen NK, Pfeiffer P, et al. Clinical and electrodiagnostic findings in breast cancer patients with radiation-induced brachial plexus neuropathy. Acta Neurol Scand. 1990;81:153-158.

49 Berk T, Cohen Z, McLeod RS, et al. Management of mesenteric desmoid tumours in familial adenomatous polyposis. Can J Surg. 1992;35:393-395.

50 Itoh H, Ikeda S, Oohata Y, et al. Treatment of desmoid tumors in Gardner’s syndrome. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:459-461.

51 Tsukada K, Church JM, Jagelman DG, et al. Noncytotoxic drug therapy for intra-abdominal desmoid tumor in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:29-33.

52 Wilcken N, Tattersall MH. Endocrine therapy for desmoid tumors. Cancer. 1991;68:1384-1388.

53 Fong Y, Rosen PP, Brennan MF. Multifocal desmoids. Surgery. 1993;114:902-906.

54 Posner MC, Shiu MH, Newsome JL, et al. The desmoid tumor. Not a benign disease. Arch Surg. 1989;124:191-196.

55 Spinner RJ, Atkinson JL, Scheithauer BW, et al. Peroneal intraneural ganglia: the importance of the articular branch. Clinical series. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:319-329.

56 Bataskis JG. Tumors of the Head and Neck: Clinical and Pathological Considerations. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1974. 231-240

57 Burger PC, Vogel FS. Surgical Pathology of the Nervous System and Its Coverings. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1982.

58 Curtis RM, Clark G. Tumors of the blood and lymphatic vessels. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1991.

59 Giannini C, Scheithauer BW, Hellbusch LC, et al. Peripheral nerve hemangioblastoma. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:999-1004.

60 Brodkey JA, Buchignani JA, O’Brien TF. Hemangioblastoma of the radial nerve: case report. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:198-200.

61 Stout AP. Tumors featuring pericytes; glomus tumor and hemangiopericytoma. Lab Invest. 1956;5:217-223.

62 Johnson PC, Kline DG. Localized hypertrophic neuropathy: possible focal perineurial barrier defect. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 1989;77:514-518.

63 Gruen JP, Mitchell W, Kline DG. Resection and graft repair for localized hypertrophic neuropathy. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:78-83.

64 Peckham NH, O’Boynick PL, Meneses A, et al. Hypertrophic mononeuropathy. A report of two cases and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1982;106:534-537.

65 de los Reyes RA, Chason JL, Rogers JS, et al. Hypertrophic neurofibrosis with onion bulb formation in an isolated element of the brachial plexus. Neurosurgery. 1981;8:397-399.

66 Lallemand RC, Weller RO. Intraneural neurofibromas involving the posterior interosseous nerve. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1973;36:991-996.

67 Appenzeller O, Kornfeld M. Macrodactyly and localized hypertrophic neuropathy. Neurology. 1974;24:767-771.

68 Neary D, Ochoa J. Localized hypertrophic neuropathy, intraneural tumour, or chronic nerve entrapment? Lancet. 1975;1:632-633.

69 Kori SH, Foley KM, Posner JB. Brachial plexus lesions in patients with cancer: 100 cases. Neurology. 1981;31:45-50.

70 Thomas JE, Colby MYJr. Radiation-induced or metastatic brachial plexopathy? A diagnostic dilemma. JAMA. 1972;222:1392-1395.

71 Lederman RJ, Wilbourn AJ. Brachial plexopathy: recurrent cancer or radiation? Neurology. 1984;34:1331-1335.

72 Dubuisson AS, Kline DG, Weinshel SS. Posterior subscapular approach to the brachial plexus. Report of 102 patients. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:319-330.