CHAPTER 68 Belt lipectomy: Lower body lift

Physical evaluation

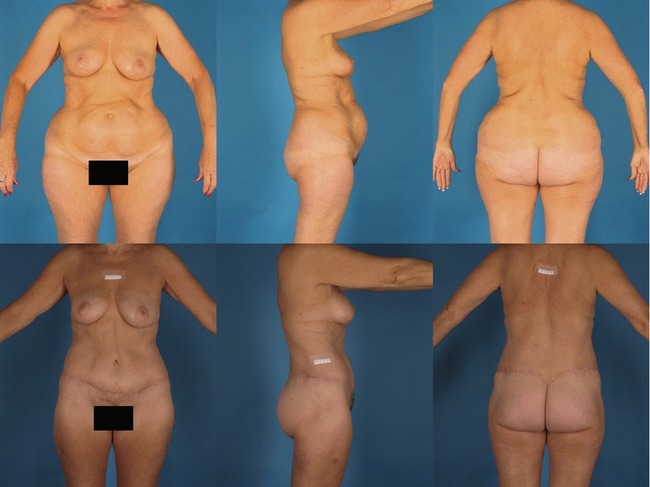

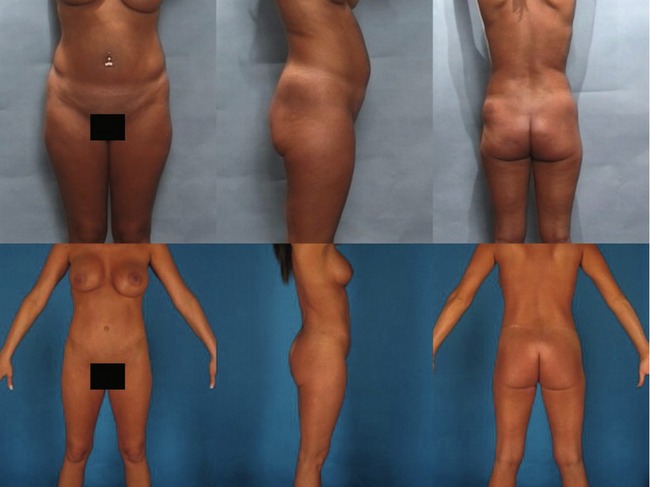

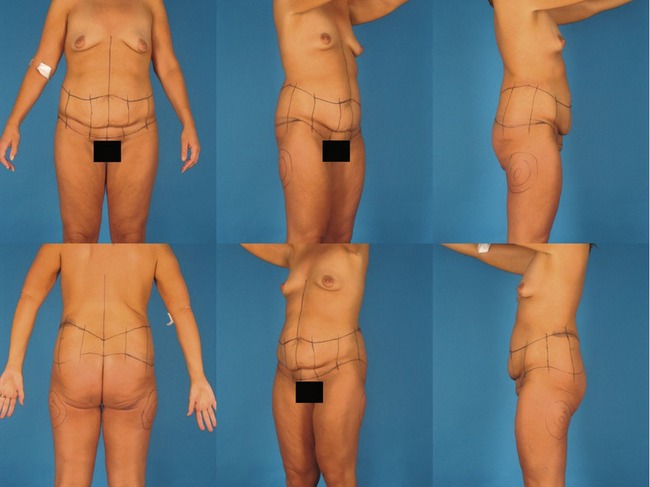

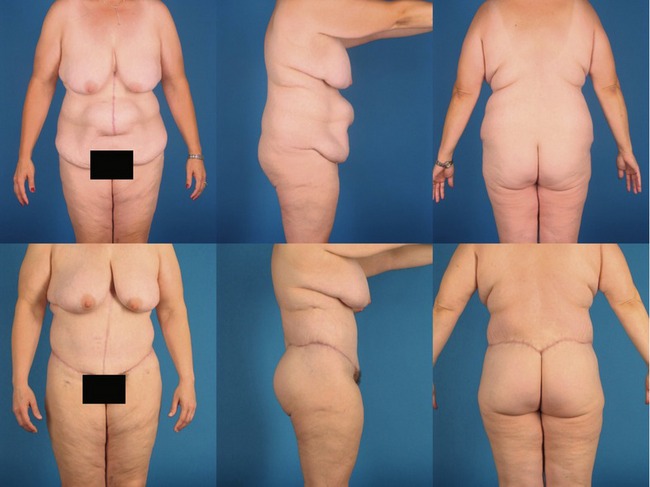

Patients who present for circumferential body lifts are most commonly massive weight loss patients. However two other groups can benefit and they include women who are 20 to 30 pounds overweight and are unable to lose that weight (Fig. 68.1), and a group of normal weight women who desire a remarkable improvement in their overall lower truncal contour (Fig. 68.2). Most of our comments here address the massive weight loss patient, who makes up 90% of patients who undergo belt lipectomy in our practice.

A complete history is taken and physical exam carried out, emphasizing:

• Weight loss history including which bariatric procedure if applicable.

• Length of time weight has been stable; at least 3 to 6 months prior to considering body contouring.

• Recording the highest and presenting body mass index (BMI) calculated by dividing the patient’s weight in kilograms by their height in meters squared.

• Rule out active medical and psychological problems and obtain a psychological clearance for surgery.

• Check that intra-abdominal content has decreased enough to allow abdominal wall plication to flatten out the abdomen.

• Evaluate the extent of tissue movement by pinching the truncal tissues and determining how far away from the proposed area of resection the effect will translate, a process we call “the translation of pull” (Fig. 68.3).

• Extensive set of laboratory examinations that target post-bariatric nutritional deficiencies such as iron, total protein, albumin, calcium, etc.

• Discuss extensively the risks and complications of the surgery.

Anatomy

To understand how tissues act under the burden of massive weight loss it is important to understand the “zones of adherence”. These zones act as hooks upon which tissues hang. They vary in strength with strong adherence located at the sternum, midline of the back, the femoral/inguinal region and a zone located between the hip and lateral thigh fat deposits. A variable amount of adherence is located in the suprapubic region.

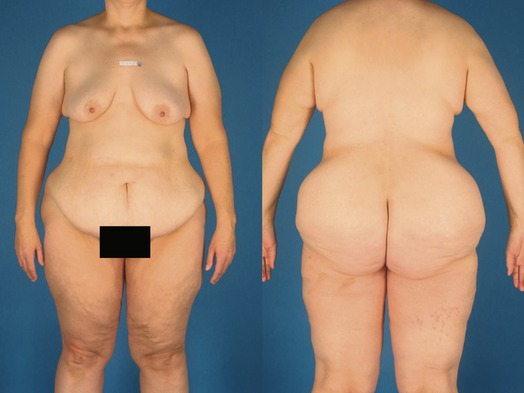

The presentation of the massive weight loss patients is quite variable and it depends on the BMI, the fat deposition pattern, and quality of the skin–fat envelope. The abdomen or back may have multiple rolls, one roll, or no rolls and a redundant ptotic mons pubis, usually with both vertical and horizontal excess. The entire lower trunk has an inverted cone appearance in almost all massive weight loss patients (Fig. 68.4). Usually the buttocks are both ill-defined and ptotic; sometimes deflated and sometimes overprojected.

Technical steps

Markings

The anterior midline is marked first. With the mons pubis superiorly elevated to a pleasing appearance a horizontal pubic mark is made 1 to 2 cm above the level of the pubic bone and it ranges from one edge of the hair-bearing surface to the other. From this edge, another marking is made toward the anterior superior iliac spine with the abdominal tissues medially and superiorly elevated, to simulate the tension at closure, and thus help to accurately predict final scar position. Both sides are measured and then matched for symmetry. The pinch technique will determine the superior marking of the proposed excision. It is important to avoid acute angulation in the antero-lateral superior marking because the abdominal flap may be vascularly compromised. Overall the position of scar anteriorly is controlled by the position of the inferior marks.

Posteriorly the vertical midline is marked and the midline inferior limit of the resection is decided upon generally at the level of the top intergluteal crease, but this will vary depending on patient anatomy. The tissue is then pinched in the midline with the patient bent at the waist, to simulate the position the patient will be in after the anterior resection is performed, and the superior mark is made. Performing this mark with the patient bent is essential to prevent dehiscence. The inferior postero-lateral markings are made in a lazy “S” shape, at the junction of the smooth lower back skin and the dimpled buttocks skin. The superior postero-lateral marks are made by using the inferior marks to pinch up to a superior level and concomitantly evaluating the buttocks and lateral thigh contour. The superior marks in the midline are brought to a “V”-shaped dip. Overall final scar position in the postero-lateral aspect of a belt lipectomy will be controlled by the superior marks and will on the average be around 2.5 cm inferior to those marks. Figure 68.5 demonstrates a typical patient’s markings.

Surgical steps

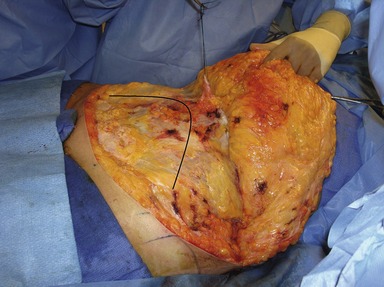

Prior to surgery the patient has an epidural catheter placed to manage postoperative pain and potentially reduce venous thrombosis; a urinary bladder catheter is inserted; and sequential compression boots are placed and turned on prior to induction of general anesthesia. The surgery starts with the patient in the supine position. A circumbilical incision is made and blunt scissor dissection is used to dissect the stalk down to the level of the underlying muscle fascia. The inferior abdominal mark is incised first to Scarpa’s fascia level and abdominal flap is elevated superiorly to just above the level of the umbilicus (Fig. 68.6). The extent of dissection above the umbilicus is dependent on whether the panniculus is thick and will require liposuction, in which case it should be as narrow as possible, just enough to allow the appropriate abdominal wall plication. In patients with thin panniculi that do not require liposuction, the dissection can be more aggressive but it should always be just enough to allow for appropriate flap advancement. Abdominal wall plication is made in two vertical layers; the first is performed with an interrupted permanent 0 size braided suture and the second layer is a permanent monofilament #1 running suture. If the abdominal wall has persistent vertical laxity, horizontal rows of plication may be needed. Anterior thigh liposuction is performed in the supine position if needed. The patient is flexed at the waist and the abdominal flap is advanced inferiorly and tailored. Two drains are placed through separate stab incisions, usually lateral to the pubic region. The position of neo-umbilicus is determined by making a 1.5 to 2.0 cm vertical midline incision overlying the umbilicus and creating a path for the umbilicus to come through without resecting fat. The umbilicus is sutured at 3, 6 and 9 o’clock positions, with 3-point fixation sutures utilizing 3-0 monocryl from the surrounding abdominal fascia, to the umbilical subdermis to the abdominal flap subdermis. The reminder of the umbilicus is re-approximated with simple interrupted 3-0 monocryl inverted subcuticular sutures. Closure of the abdomen is performed in layers. The deep layer incorporates the superficial fascia system (Scarpa fascia anteriorly), up to and including the subdermis, with a long-lasting 0 sized monofilament suture, usually in an interrupted fashion. A second subcuticular layer is sutured with 2-0 or/and 3-0 monocryl in an inverted interrupted fashion. Skin glue is applied to all wounds including the umbilicus.

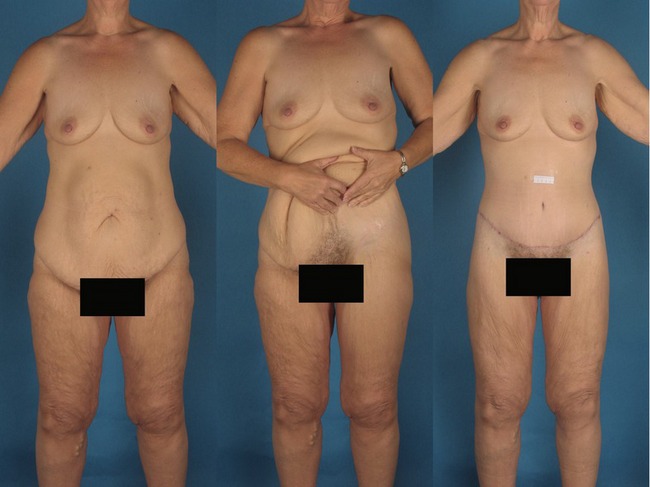

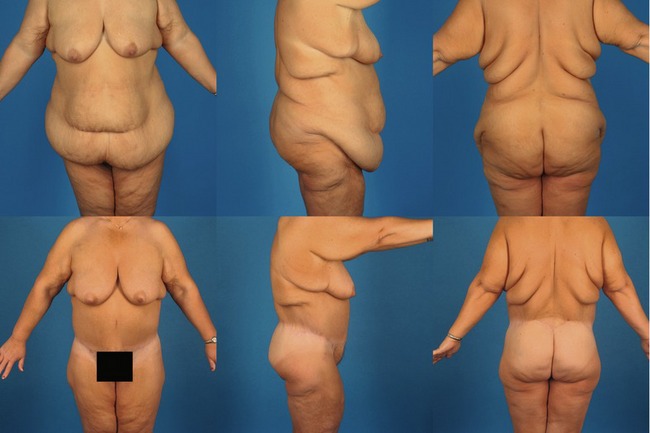

Fig. 68.8 An intermediate BMI patient, 30 to 35, is shown before (above) and after belt lipectomy (below). The patient had a large ventral hernia that involved the umbilicus, which was sacrificed. Patients in this range of weight will attain intermediate results between the high BMI patients (Fig. 68.7) and the low BMI patients (Fig. 68.9).

Complications

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• The patient should be very well prepared physically and psychologically, because the belt lipectomy is a major event in a patient’s life.

• Knowing where and how the zones of adherence occur allows the surgeon to control scar position.

• The final scar position will be determined by the inferior incision in the anterior abdomen and by the superior incision in the lateral and posterior trunk.

• Markings are the essence of the procedure.

• It is important to incorporate the superficial fascial system during the deep closure.

• Results are dependent on BMI level on presentation, fat deposit pattern, and the quality of the skin fat envelope.

• Complications are not uncommon with the seroma being the most common problem.

• An interdisciplinary team is important to follow these patients (physiotherapist, bariatric surgeon, nutritionist, general clinician, psychologist, psychiatrist, plastic surgeon, nurse, plastic surgeon).

Pitfalls

• The posterior resection in a belt lipectomy should not compromise the anterior or lateral contours: “The money is in the belly”.

• Avoid psychiatrically unstable patients and make sure that their psychological care giver is willing to help with potential postoperative problems.

• A clear understanding of the blood supply of the abdominal flap is essential in choosing the correct method of dealing with the anterior resection, especially in patients who have upper abdominal cholycystectomy scars.

• Avoid performing too much surgery and long operating times. Patients often will want to achieve more than is safe in a single operation, and the surgeon should be the one who educates the patient on what is safe to do and what is not.

Summary of steps

1. The anterior midline is marked first.

2. The pinch technique determines the superior marking of the proposed excision.

3. Posteriorly the vertical midline is marked and the midline inferior limit of the resection is decided upon.

4. Performing the superior mark with the patient bent is essential to prevent dehiscence.

5. The postero-lateral marks are then made.

6. A circumbilical incision is made and blunt scissor dissection is used to dissect the stalk down to the level of the underlying muscle fascia.

7. Abdominal wall plication is made in two vertical layers.

9. The patient is turned to the lateral decubitus position keeping the waist flexed.

10. The superior back marking is incised from the lateral dog ear to the midline of the back and the dissection is taken down just above the level of the muscle fascia in patients who have excess buttocks projection.

11. Lateral thigh liposuction is performed and if necessary discontinuous undermining is performed with either a large liposuction cannula or a “Lockwood elevator”.

13. The patient is then turned to the opposite lateral decubitus position and the same exact procedure is performed on the opposite side.

Aly AS, Cram AE. Belt lipectomy. In: Aly AS, ed. Body contouring after massive weight loss. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2006:71–145.

Aly A, Cram AE, Chao BS, et al. Belt lipectomy for circumferential truncal excess: The University of Iowa Experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:398.

Capella JF, Oliak DA, Nemerofsky RB. Body lift: an account of 200 consecutive cases in the massive weight loss patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:414.

Rohrich R, Kenkel J, et al. Body contouring surgery after massive weight loss supplement. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(1):1.