chapter 7 Behaviour change strategies

AUTONOMY

Helping people change high-risk behavior will be the key to prevention. To develop more effective prevention programs, we will have to train a new generation of experts who can not only provide people with risk information but also work with them as partners in achieving mutually agreed upon goals.1

To illustrate this point, a study on the association between work stress (job strain and effort–reward imbalance) and the risk of death from cardiovascular disease found a strong association. Over 800 employees were followed up for 25 years. It was found that high job strain (high demands, low job control) led to more than a doubling of the risk of dying from heart disease compared with those with low job strain.2 An effort–reward imbalance (low salary, lack of social approval and few career opportunities relative to efforts required at work) produced a similar effect. Noting the association is interesting. Intervening to mitigate its effects, though, is far more useful.

ENABLING STRATEGIES

Much of the time a healthcare practitioner can think it is enough to provide health information and let the case for behaviour change rest on that. Saying, for example, that smoking is bad for one’s health and providing some medical reasons for that will increase the smoking cessation rate over the next year from about 1% to 2%. When enabling strategies are included with the information it is far more effective and, in the case of smoking cessation rates, quit rates can be improved to around 30% or higher. Examples of enabling strategies that will help to facilitate healthy change include: behaviour change skills, motivation, empowerment, health coaching principles, the behaviour change cycle and goal setting. The ESSENCE model (see Ch 6) may also help to give structure to a total lifestyle plan.

MOTIVATION

One way of clarifying and galvanising motivation is to use the cycle of behaviour change model, which is described in more detail later in this chapter. Another way is for the patient to write down on a piece of paper all the costs and benefits of making or not making a particular change. An example is given in Table 7.1.

TABLE 7.1 Costs and benefits of changing or not changing behaviour to include regular exercise

| Changing | Not changing | |

|---|---|---|

| Benefits |

Having done this, the next step is to look at the things standing in the way of healthy change and then to consider how valid or fixed they are. Take cost as an example. The preferred form of exercise might be skiing, but this is not very accessible and has a high financial cost. But exercise can also be relatively inexpensive—walking is an example. Furthermore, exercise can reduce a significant financial and time burden by reducing the likelihood of becoming ill and needing time off work. Rather than costing money, it is likely to save money. In truth, being sedentary may be the far more expensive option. A similar process can be followed for each factor, such as tiredness—exercise increases energy and vitality. If there is a concern about injury then it will be important to choose a form of exercise suitable for the person’s current age and level of fitness—what is appropriate for a 20-year-old may not be appropriate at age 50.

PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS

A number of psychological factors are important enabling strategies. These factors include stress management, attention regulation and emotional regulation. These will be dealt with in the mind–body chapter (Ch 8).

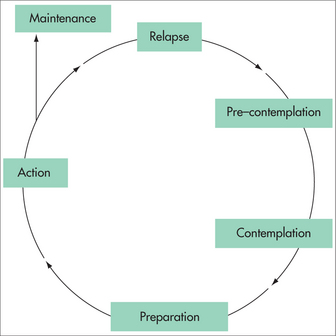

PROCHASKA DICLEMENTE CYCLE OF BEHAVIOUR CHANGE

The Prochaska DiClemente cycle of behaviour change is a model initially developed to explain the steps we go through in changing a behaviour. It has been used widely in health and psychology settings for various behaviours, although it was initially applied to smoking cessation. It is applicable to almost any behaviour and can be adapted as such. The steps in the process are outlined in Figure 7.1 and below.

The stages are self-explanatory but there are some important points to remember when implementing the process. Early in the process it is important to determine which stage a person is in. Knowing the stage helps one to tailor questions, direct information, enhance motivation and provide skills relevant to that stage. Trying to encourage action, for example, before a person has clarified their motivation will be inappropriate and is almost certain to fail. The art is to move through the stages from where the person is currently and in a way that is suitable for their needs and motivation.

SMART GOAL-SETTING

Time dependent

It is useful for a goal to have a specific time frame rather than being too open-ended. This can increase focus and maintain motivation. For example, a person may aim to be fit enough to compete in a fun run in 6 months’ time. As such it can help a person to stay focused and not become complacent. This helps us to make our goals specific, map our progress, provide incentive and keep goals realistic.

BASK

Interventions can be directed at any or all of the above dimensions. The Ornish program (which will be described in detail in the chapters on heart disease (Ch 25) and cancer (Ch 24)) is a good example of a program that contains all these aspects contained in BASK. That is largely why the program is so successful.

HEALTH PROMOTION3

A population approach to health promotion is far more cost-effective than treating individuals. This is well illustrated in the reduced rates of many infectious diseases through immunisation. Illnesses such as measles are uncommon now. Polio is rare. Smallpox has been eradicated. Other examples of major health promotion successes include:

Now fewer than 17% of adults smoke, whereas the figure was around 72% among males in the middle of the twentieth century.4,5 The effects of this change will be increasingly felt in coming generations as the rates of smoking-related illnesses decline. In developed countries, road tolls have more than halved over the past 30 years.6 This is despite a doubling of the population and an even larger increase in the number of cars on the road. The number of new HIV/AIDS cases diagnosed per year has dropped significantly in most developed countries, due largely to public campaigns promoting safe sex and harm minimisation among drug users being strongly reinforced by healthcare practitioners. Skin cancer rates—most importantly the rates of malignant melanoma—have plateaued in recent years in places where sunburn rates have been reduced. In Victoria, Australia, for example, there has been a 60% decline in weekend sunburn rates over the past 20 years.7 Sun-smart campaigns have been implemented not just through medical practices but also in schools and via social marketing.

VicHealth figures suggest that, per life year gained, the cost of smoking prevention is approximately 1/500th that of treating lung cancer. In Australia, the treatment for AIDS in the early 1990s cost over $46 000 per life year gained, whereas it only costs $185 per life year gained when the money is spent on preventing HIV infection.8

Effective health promotion depends on a number of factors, and these are outlined below.9

Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations. http://www.afao.org.au.

Australian Health Promotion Association. http://www.healthpromotion.org.au.

Cancer Council of Victoria. http://www.accv.org.au.

International Union for Health Promotion and Education. http://www.iuhpe.org.

Public Health Association of Australia. http://www.phaa.net.au.

Quit Program. http://www.quit.org.au.

1 Syme SL. Psychosocial interventions to improve successful aging. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(5/2):400-402.

2 Kivimaki M, Leino-Arjas P, Luukkonen R, et al. Work stress and risk of cardiovascular mortality: prospective cohort study of industrial employees. BMJ. 2002;325(7369):857.

3 This section draws upon principles outlined in the Monash University Health Promotion course in 2007 by Dr Rob Moodie, the then CEO of VicHealth.

4 State Government, Victoria. Quit Victoria. Smoking rates in Victoria. Online. Available: http://www.quit.org.au/article.asp?ContentID=7241.

5 State Government, Victoria. Quit Victoria. Smoking rates in Australia. Online. Available: http://www.quit.org.au/article.asp?ContentID=7240.

6 State Government, Victoria. Transport Accident Commission. Online. Available: http://www.tacsafety.com.au/jsp/content/NavigationController.do?areaID=12.

7 Davis KJ, Cokkinides VE, Weinstock MA, et al. Summer sunburn and sun exposure among US youths ages 11 to 18: national prevalence and associated factors. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1):27-35.

8 VicHealth (Victorian Health Promotion Foundation). Online. Available: www.vichealth.vic.gov.au.

9 Moodie R, Hulme A. Hands on health promotion. Melbourne: IP Communications, 2004.