Chapter 201 Bartonella

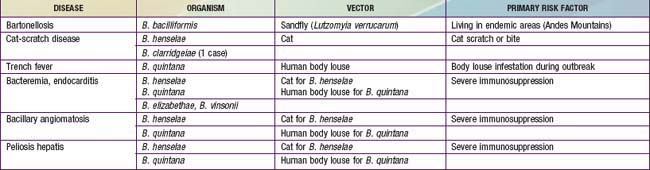

The spectrum of disease resulting from human infection with Bartonella species includes the association of bacillary angiomatosis and cat-scratch disease (CSD) with Bartonella henselae. Six major Bartonella species are pathogenic for humans: B. henselae, Bartonella quintana, Bartonella bacilliformis, Bartonella elizabethae, Bartonella vinsonii, and Bartonella clarridgeiae (Table 201-1). Several other Bartonella species have been found in animals, particularly rodents and moles.

201.1 Bartonellosis (Bartonella bacilliformis)

Clinical Manifestations

In the pre-eruptive stage of verruca peruana (Fig. 201-1), patients may complain of arthralgias, myalgias, and paresthesias. Inflammatory reactions such as phlebitis, pleuritis, erythema nodosum, and encephalitis may develop. The appearance of verrucae is pathognomonic of the eruptive phase. Lesions vary greatly in size and number.

201.2 Cat-Scratch Disease (Bartonella henselae)

Clinical Manifestations

After an incubation period of 7-12 days (range 3-30 days), 1 or more 3- to 5-mm red papules develop at the site of cutaneous inoculation, often reflecting a linear cat scratch. These lesions are often overlooked because of their small size but are found in at least 65% of patients when careful examination is performed (Fig. 201-2). Lymphadenopathy is generally evident within a period of 1-4 wk (Fig. 201-3). Chronic regional lymphadenitis is the hallmark, affecting the 1st or 2nd set of nodes draining the entry site. Affected lymph nodes in order of frequency include the axillary, cervical, submandibular, preauricular, epitrochlear, femoral, and inguinal nodes. Involvement of more than 1 group of nodes occurs in 10-20% of patients, although at a given site, half the cases involve several nodes.

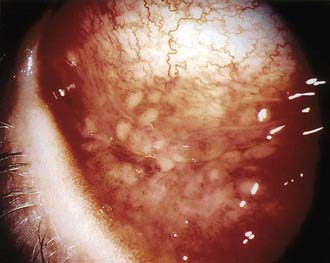

CSD is usually a self-limited infection that spontaneous resolves within a few weeks to months. The most common atypical presentation is Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome, which is unilateral conjunctivitis followed by preauricular lymphadenopathy and occurs in 2-17% of patients with CSD (Fig. 201-4). Direct eye inoculation as a result of rubbing with the hands after cat contact is the presumed mode of spread. A conjunctival granuloma may be found at the inoculation site. The involved eye is usually not painful and has little or no discharge but may be quite red and swollen. Submandibular or cervical lymphadenopathy may also occur.

More severe, disseminated illness occurs in a small percentage of patients and is characterized by presentation with high fever, often persisting for several weeks. Other prominent symptoms include significant abdominal pain and weight loss. Hepatosplenomegaly may occur, although hepatic dysfunction is rare (Fig. 201-5). Granulomatous changes may be seen in the liver and spleen. Another common site of dissemination is bone, with the development of granulomatous osteolytic lesions, associated with localized pain but without erythema, tenderness, or swelling. Other uncommon manifestations are neuroretinitis with papilledema and stellate macular exudates, encephalitis, fever of unknown origin, and atypical pneumonia.

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of CSD includes virtually all causes of lymphadenopathy (Chapter 490). The more common entities include pyogenic lymphadenitis, primarily from staphylococcal or streptococcal infections, atypical mycobacterial infections, and malignancy. Less common entities are tularemia, brucellosis, and sporotrichosis. Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and Toxoplasma gondii infections usually cause more generalized lymphadenopathy.

Arisoy ES, Correa AG, Wagner ML, et al. Hepatosplenic cat-scratch disease in children: selected clinical features and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:778-784.

Bass JW, Freitas BC, Freitas AD, et al. Prospective randomized double blind placebo-controlled evaluation of azithromycin for treatment of cat-scratch disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:447-452.

Batts S, Demers DM. Spectrum and treatment of cat-scratch disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:1161-1162.

Carithers HA, Margileth AM. Cat scratch disease: acute encephalopathy and other neurologic manifestations. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145:98-101.

Fournier PE, Lelievre H, Ekyn SJ, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of Bartonella quintana and Bartonella henselae endocarditis: a study of 48 patients. Medicine. 2001;80:245-251.

Jacobs R, Schutze G. Bartonella henselae as a cause of prolonged fever and fever of unknown origin in children. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:80-84.

Metzkor-Cotter E, Kletter Y, Avidor B, et al. Long-term serological analysis and clinical follow-up of patients with cat scratch disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1149-1154.

Ormerod LD, Dailey JP. Ocular manifestations of cat-scratch disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1999;10:209-216.

201.4 Bacillary Angiomatosis and Bacillary Peliosis Hepatis (Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana)

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of BA is made initially by biopsy. The characteristic small vessel proliferation with mixed inflammatory response and the staining of bacilli by Warthin-Starry silver staining distinguish BA from pyogenic granuloma or Kaposi sarcoma (Chapter 254). Travel history can usually preclude verruca peruana.

Florin TA, Zaoutis TE, Zaoutis LB. Beyond cat scratch disease: widening spectrum of Bartonella henselae infection. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1413-e1425.

Inoue K, Maruyama S, Kabeta H, et al. Exotic small mammals as potential reservoirs of zoonotic Bartonella spp. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:526-532.

Rolain JM, Brouqui P, Koehler JE, et al. Recommendations for the treatment of human infections caused by Bartonella species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1921-1933.