Bacterial, spirochete, and protozoan infections

An infectious disease atlas can be found in the on-line content for this book.

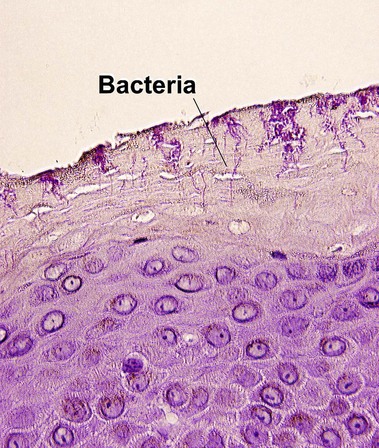

Bacterial diseases

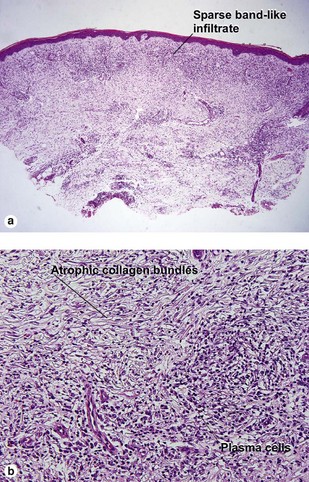

Leprosy

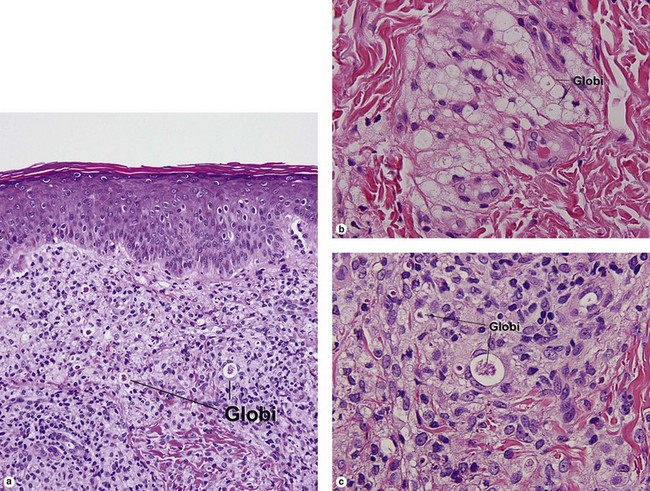

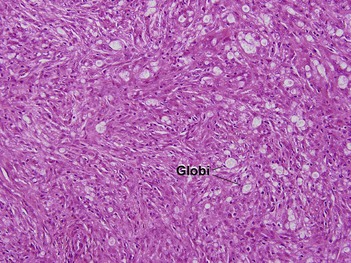

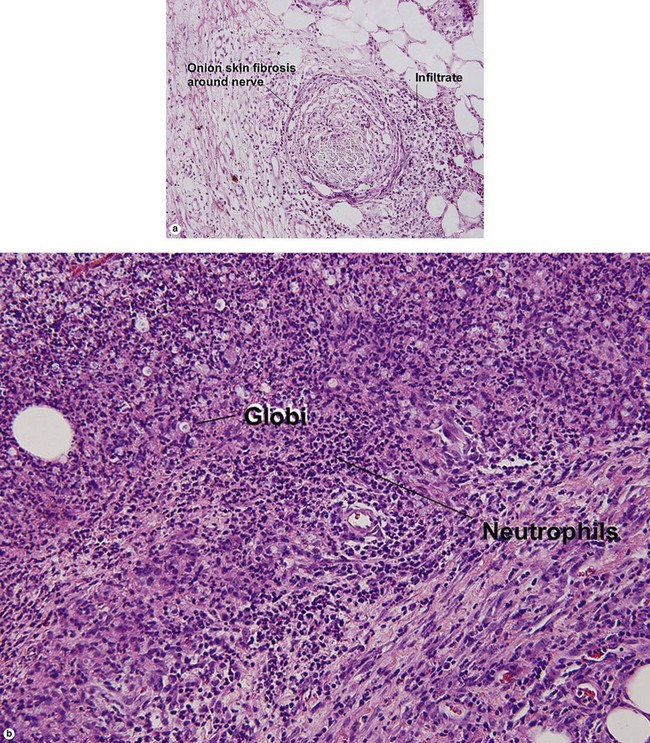

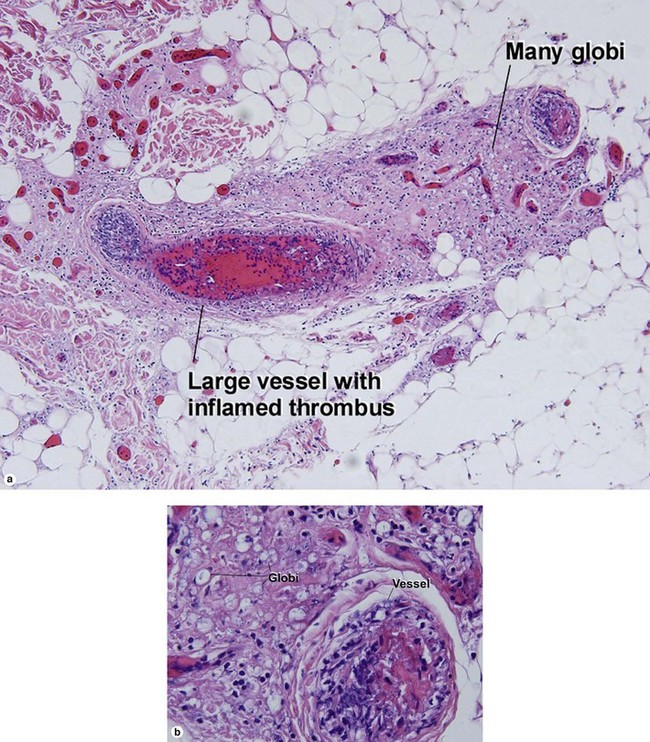

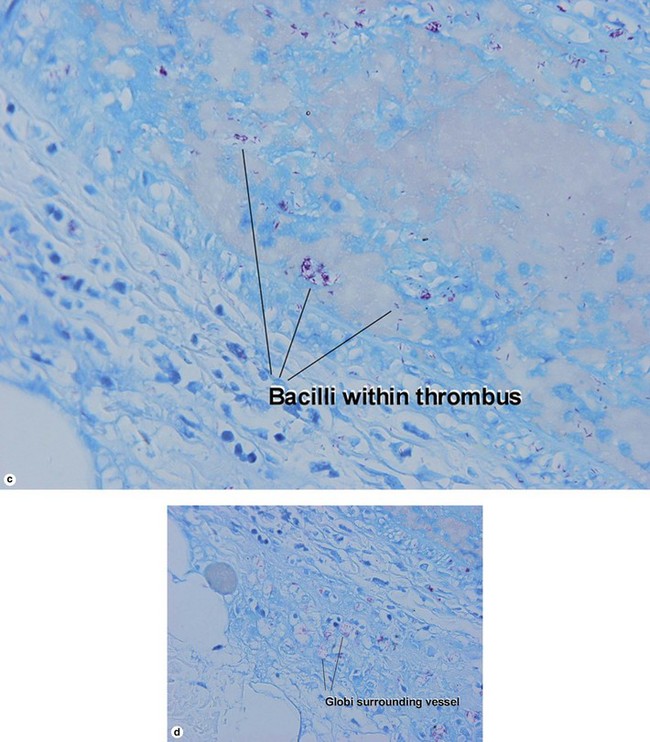

Lepromatous leprosy

Globi are amphophilic collections of mycobacteria. The organisms stain strongly with a Fite stain.

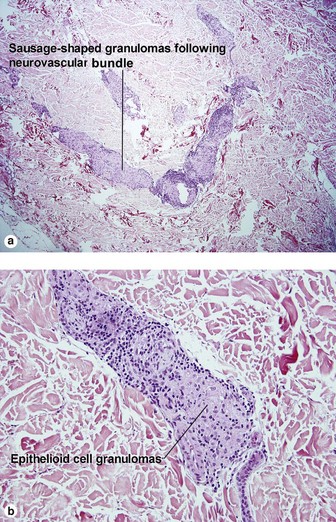

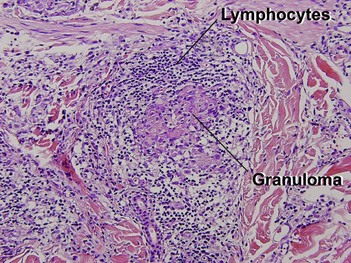

Leprosy reactions

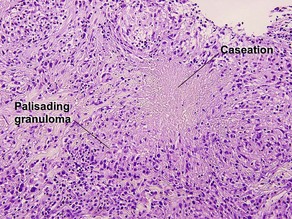

Type 1: reversal or downgrading reaction

Reversal reactions commonly occur after antibiotic therapy is initiated. In response to antibiotic treatment, the patient regains a greater degree of cellular immunity. The increased type IV immune response inflicts damage on the neurovascular bundle.

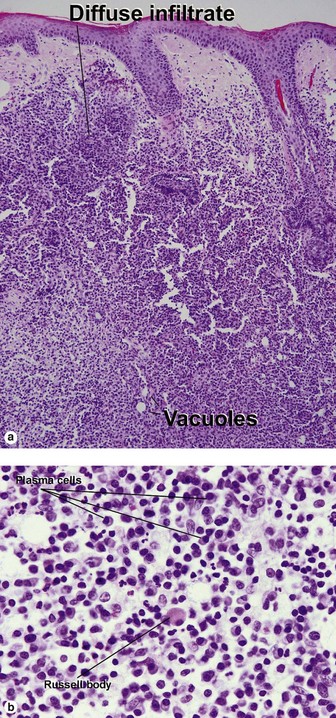

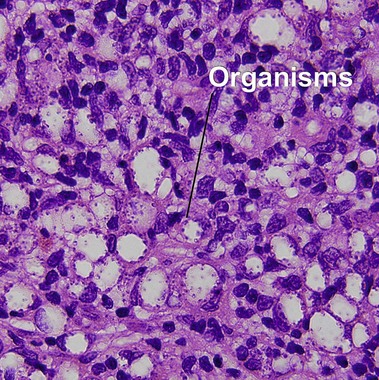

Spirochete-mediated diseases

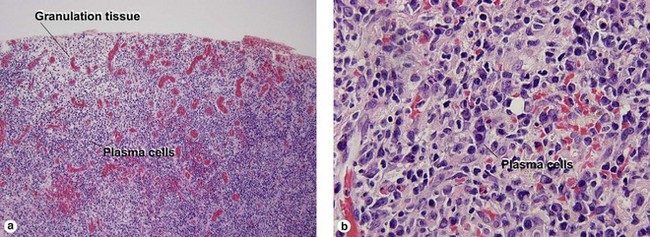

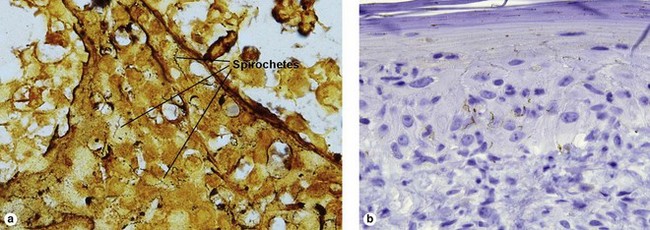

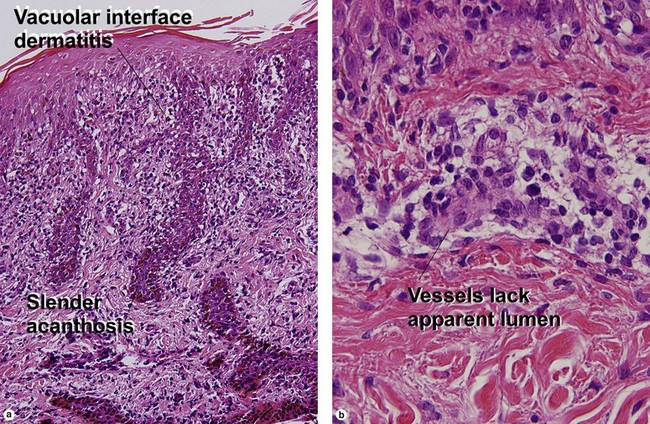

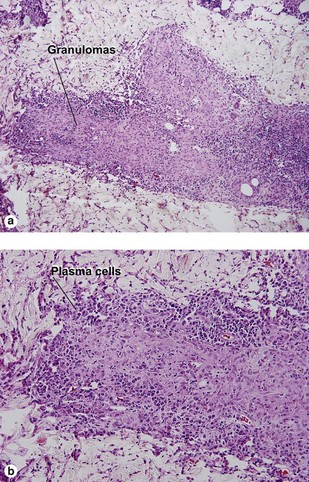

Secondary syphilis

Secondary syphilis is highly variable in its clinical presentation, and almost as variable in its histologic appearance. Any suspicious feature should prompt an immunostain or silver stain, clinical evaluation, and serologic studies. False-negative prozone reactions are the result of massive antibody excess. Antigen–antibody complexes form most efficiently with mild antigen excess and can be inhibited by massive antibody excess. The serum may need to be diluted many-fold in order to test positive.

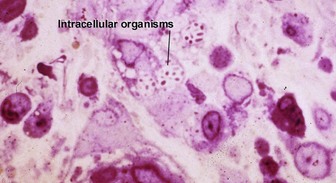

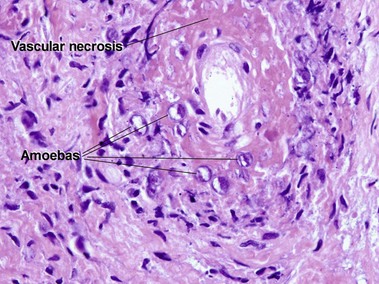

Protozoan diseases

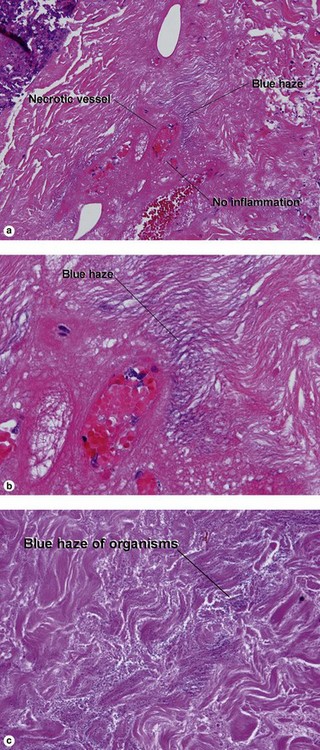

Acanthamoeba

At first glance, amoeba trophozoites may look like large histiocytes with somewhat refractile nuclei. Glance again. They have a characteristic appearance, as noted in Figure 17.23. Vascular invasion and necrosis are typical. Lobular fat necrosis has been reported. Disseminated disease is frequently associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or immunosuppressive drugs. Cultures on an agar plate seeded with a lawn of Escherichia coli will demonstrate characteristic tracks.

Baughn, RE, Musher, DM. Secondary syphilitic lesions. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005; 18(1):205–216.

Blonski, KM, Blödorn-Schlicht, N, Falk, TM, et al. Increased detection of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Norway by use of polymerase chain reaction. APMIS. 2012; 120(7):591–596.

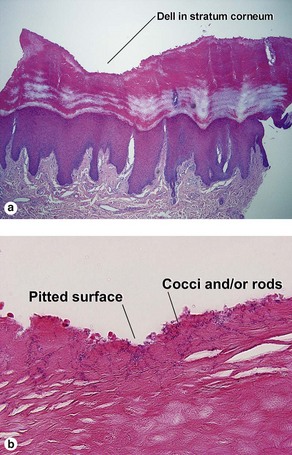

de Almeida, HL, Jr., de Castro, LA, Rocha, NE, et al. Ultrastructure of pitted keratolysis. Int J Dermatol. 2000; 39(9):698–701.

Engelkens, HJ, ten Kate, FJ, Vuzevski, VD, et al. Primary and secondary syphilis: a histopathological study. Int J STD AIDS. 1991; 2(4):280–284.

Kaur, C, Thami, GP, Mohan, H. Lucio phenomenon and Lucio leprosy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005; 30(5):525–527.

Lockwood, DN, Nicholls, P, Smith, WC, et al. Comparing the clinical and histological diagnosis of leprosy and leprosy reactions in the INFIR cohort of Indian patients with multibacillary leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012; 6(6):e1702.

Mathur, MC, Ghimire, RB, Shrestha, P, et al. Clinicohistopathological correlation in leprosy. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2011; 9(36):248–251.

McBroom, RL, Styles, AR, Chiu, MJ, et al. Secondary syphilis in persons infected with and not infected with HIV-1: a comparative immunohistologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999; 21(5):432–441.

Moreno, C, Kutzner, H, Palmedo, G, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with histiocytic pseudorosettes: a new histopathologic pattern in cutaneous borreliosis. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi DNA sequences by a highly sensitive PCR-ELISA. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003; 48(3):376–384.

Pandhi, RK, Singh, N, Ramam, M. Secondary syphilis: a clinicopathologic study. Int J Dermatol. 1995; 34(4):240–243.

Raval, RC. Various faces of Hansen’s disease. Indian J Lepr. 2012; 84(2):155–160.

Vargas-Ocampo, F. Analysis of 6000 skin biopsies of the national leprosy control program in Mexico. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 2004; 72(4):427–436.

Wilson, TC, Legler, A, Madison, KC, et al. Erythema migrans: a spectrum of histopathologic changes. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012; 34(8):834–837.

Wohlrab, J, Rohrbach, D, Marsch, WC. Keratolysis sulcata (pitted keratolysis): clinical symptoms with different histological correlates. Br J Dermatol. 2000; 143(6):1348–1349.