Chapter 5 Back and related limb neurological problems

5.1 Introduction

History

The aim of history taking and examination relating to any body system is to determine:

Stiffness is a rather vague term that may be related to pain, muscle spasm or deformity. It is the pattern of the stiffness may be more enlightening — early morning stiffness may be more in keeping with an inflammatory arthritis, post-activity stiffness to a degenerative process and continuous stiffness to a bony deformity that impedes motion. Acute deformity may lead one to suspect joint instability or fracture that may be related to an acute process, such as trauma, or a chronic process that destabilises the integrity of the skeletal elements, such as infection or tumour. However, acute painful deformity is also seen in degenative cases.

Examination

Movements of the spine are next observed, beginning with flexion (touching the toes). Most flexion takes place at the lumbar spine. Isolating the precise range of motion in the spine in the various segments of the spine is difficult. Forward flexion is often a combination of movement at the spine and pelvis/hips. Assessment often entails the pelvis being stabilised during the examination process. With the pelvis stabilised, the range of forward lumbar flexion may be assessed. You may measure the change in distance between a fixed point on the sacrum such as the spinous process adjacent to the S2 dimple and the first lumbar vertebra. The patient may show deviation to the painful side on forward flexion. While hip flexion may simulate spinal flexion, the lumbar lordosis will be observed not to unwind, the spine remaining stiff — in this situation the excursion between lumbar spinous processes remains unchanged as flexion proceeds. Whole spine rigidity may be evident in ankylosing spondylitis; this may be associated with a decreased chest expansion during inspiration of less than 2.5 cm.

Examination with the patient supine. A careful neurological examination of the lower limbs is performed, starting with inspection for wasting or other signs, followed by an assessment of tone, then a systematic examination of muscle strength, comparing each side to the other, as well as with your expectation of normal. It is best to start distally, as pain can compound the assessment of proximal strength. Dorsiflexion of the toes is important as this may be reduced in L5 lesions. Inversion and eversion of the ankles should be tested, as well as dorsi and plantar flexion, then flexion and extension at knee and hip. In interpreting these observations, it is essential to be familiar with the myotomes and dermatomes, as outlined in standard anatomy texts.

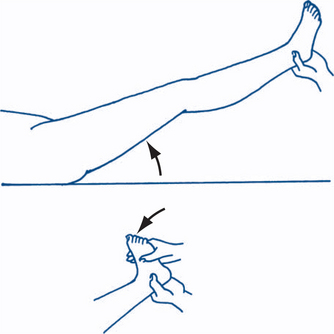

Subsequently, the straight leg raising (SLR) and flexed leg raising tests are performed. It is best to elevate the flexed leg first to observe the patient’s response, then perform rotation and adduction/abduction of the hip to assess for pathology at the hip/pelvic level. Subsequently, the extended leg is lifted actively by the patient and then by the clinician until pain in the buttock, leg and/or back is felt and the angle at which this occurs is observed. The leg should be raised slowly and the knee kept at full extension during this manoeuvre. At this level, if the knee is flexed the pain of nerve root irritation should abate and, if the ankle is dorsiflexed, the pain is exacerbated. Sudden firm pressure on the tibial nerve in the popliteal fossa may elicit further pain — sometimes known as the bowstring sign — and confirm an underlying organic aetiology. Straight leg raising of the opposite leg giving rise to pain in the affected leg is known as crossover pain, suggesting that the disc lesion is in the axilla of the nerve root or medial to the nerve root (Fig 5.1). Sciatica due to nerve root compression in the lumbar spine will typically cause pain down the back of the leg on the straight leg raise but not with the flexed leg raise. Cadaver studies have shown that the L5 and S1 nerve roots move by 2 cm or more in the spinal canal during the SLR.

Non-organic pathology may also require exclusion with the assistance of a series of signs described by Waddell. Tenderness in such cases is superficial and non-anatomical. Simulated axial loading such as pushing down on the patient’s skull or shoulders is reported as painful in the lumbar spine as is simulated rotation of the lumbar spine by rotating the shoulder and pelvis together. The pain, if present, should not be increased by this manoeuvre. Distraction tests such a extending the knee joint while the patient sits on the edge of the examination couch should produce the same pain as a straight leg raise. If it does not then the pathology may be non-organic. Regional weakness and giving way that cannot be explained on a neurological basis — myotomal/dermatomal or peripheral nerve in their pattern of involvement — should also raise suspicion. Overreaction during the examination process, such as facial expressions, tremor and collapsing, may also be suggestive of non-organic pathology. However, you must also be sensitive to cultural differences that may result in these overreactions. Inconsistency between different phases of the assessment may also be a clue. It is very common for there to be some non-organic overlay to a fundamentally organic situation.

5.2 Back pain

Special tests in the assessment of spinal pain

1 Chronic lumbar ligamentous strain

A history of pain after lifting at work is common with chronic and recurring back pain. The WorkCover context complicates the situation considerably. Most patients still get better with rest, gentle activity and time. In those cases that pass into chronic pain, the significance of neurosis or malingering in the pathogenesis of this litigation-linked condition can rarely be determined with absolute assurance. True malingering in the sense of complete fabrication of a set of symptoms and signs is uncommon; exaggeration of symptoms and signs in the absence of demonstrable organic disease and persistence of symptoms and signs while litigation is pending is common.

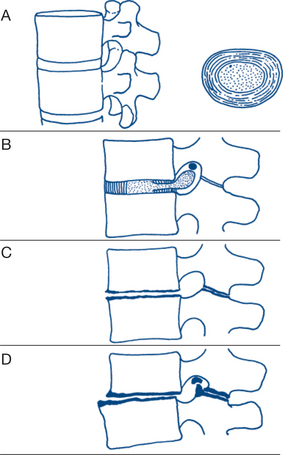

2 Degenerative disc disease, spondylosis and osteoarthritis

With disc degeneration, especially following recurrent disc prolapse, gradual flattening of the disc and displacement of the posterior facet joints occur, eventually gives rise to osteoarthritis in those joints (Fig 5.2). A past history of lumbar pain is common, with subsequent recurrent attacks of pain over a period of several years. The onset of such attacks is often related to exertional trauma, such as repetitive bending or lifting a weight, or strain from sitting in an uncomfortable position during a long journey. Sciatic radiation of the pain to the buttock and sometimes down the backs of the legs, on one or both sides, is common. With the development of osteoarthritis of the facet joints, pain becomes constant and nocturnal. On examination, tender areas may be felt over the spine. There is limitation of all lumbar spine movements and residual neurological signs of disc prolapse, such as an absent ankle jerk, may be present. Most instances of chronic recurring back pain fall into this category; however, it is surprising how many patients have minimal symtoms despite impressive changes on scans.

4 Osteoporosis

This condition is most common in elderly women; gonadal involution is the most important causal factor. Longstanding steroid therapy is an important cause, while nutritional problems may also contribute. Fractures, especially crush fractures of the vertebrae, can occur with minimal trauma. Trabecular bone stiffness varies with the cube of its density — there is almost 50% loss in strength with 30% decrease in the density. Vertebral compression fractures lead to backache, kyphosis and shortening in height. Plain X-ray reveals loss of bone density, wedging or biconcave indentation of vertebrae. Bone densitometry is a more sensitive and effective method of quantifying change in bone mineral density.

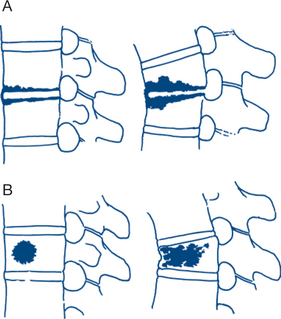

5 Secondary carcinoma of the vertebral body

The most common tumours of the vertebral bodies are metastatic lesions arising from tumours of the lung, breast, prostate, thyroid or kidney. The predominant symptom of localised destruction of the vertebral body is constant pain that steadily increases in severity. There may be associated neurological disorders because of involvement of the spinal cord or nerve roots. Plain X-ray may reveal osteolytic or osteosclerotic vertebral destruction by tumour, with preservation of an adjacent normal intervertebral disc (Fig 5.3). Metastases from carcinoma of the prostate are more commonly osteosclerotic. Considerable destruction of bone substance is necessary before radiological signs occur; X-rays are thus commonly negative in the presence of metastases. CT is more sensitive and MRI better again. Bone scans can be diagnostic. Furthermore, focal metastatic deposits can be difficult to differentiate from localised Paget’s disease.

Diagnostic plan

Collapse or destruction of the vertebral body, narrowing of the disc space and soft tissue changes may be assessed on plain X-ray, but this test is relatively insensitive. The most common X-ray features found in the spine are those of chronic disc degeneration, spondylosis, osteoarthritis and sometimes spondylolisthesis. In the case of spondylolisthesis, the early signs of narrowing of the anterior disc space and displacement of the more proximal vertebrae against the one below are seen best on the lateral view. The disc spaces most often involved are those between L4 and L5 and L5 and S1. Later, marginal osteophytes appear at the edge of the disc and there is increased radiolucency of the vertebral body. Lateral and oblique views may show facet joint malalignment and osteoarthritis.

Neurological system

History

Symptoms of neurological disease in the limbs include paralysis, clumsiness, movement disorder, anaesthesia (to pain, light touch and temperature) and paraesthesia. The full characterisation of these disorders lies outside the range of this book, and readers are referred to neurological texts.

Examination

1 Motor nerve function

Muscle power is tested by active movement against resistance. Power is graded from 0 to 5 according the criteria described by the Medical Research Council. In this system no active movement equates to a 0, a flicker of movement to a 1, movement possible but not against gravity to a 2, movement possible against gravity but not against resistance to a 3, movement against resistance but weakened to a 4 and normal power to a 5. Tables 5.1 and 5.2 indicate the spinal roots that may be tested in the upper and lower limbs. There are no half grades in this system.

Table 5.1 The nerve and spinal roots that innervate the major muscle groups of the upper limb

| Muscle action | Spinal roots | Peripheral nerves |

|---|---|---|

| Shoulder | ||

| Flexion | C5, 6 | Nerve to pectoralis major |

| Axillary nerve | ||

| Extension | C5, 6 | Subscapular nerve |

| Abduction | C5, 6 | Axillary nerve |

| Elbow | ||

| Flexion | C5, 6 | Musculocutaneous nerve |

| Extension | C7, 8 | Radial nerve |

| Wrist | ||

| Flexion | C6, 7 | Median nerve and ulnar nerve |

| Extension Finger flexion Finger extension |

C6, 7 C7, 8 C7, 8 |

Radial nerve Median and ulnar Radial |

| Intrinsic hand muscles | ||

| T1 | Median nerve and ulnar nerve | |

Table 5.2 The nerve and spinal roots that innervate the major muscle groups of the lower limb

| Muscle action | Spinal roots | Peripheral nerves |

|---|---|---|

| Hip | ||

| Flexion | L2, 3 | Lumbar and femoral nerves |

| Extension | L5, S1, 2 | Inferior gluteal nerve |

| Abduction | L4, 5, S1 | Superior gluteal nerve |

| Adduction | L2, 3, 4 | Obturator nerve |

| Knee | ||

| Flexion | L5, S1 | Sciatic nerve |

| Extension | L3, 4 | Femoral nerve |

| Ankle | ||

| Plantar flexion | S1, 2 | Tibial nerve |

| Dorsiflexion | L4, 5 | Deep peroneal nerve |

| Foot | ||

| Inversion | L4 | Tibial nerves |

| Eversion | L5, S1 | Deep peroneal nerve Toe dorsiflexion L5, deep peroneal nerve |

2 Sensory nerve function

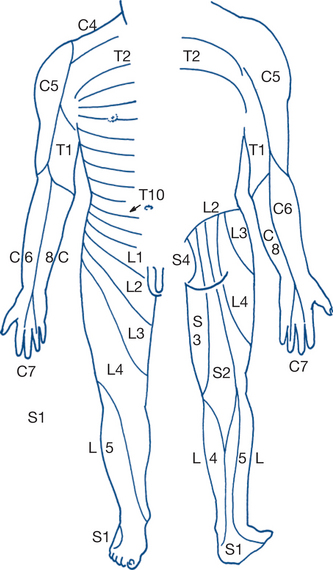

Testing of superficial touch, pain and temperature sensation is followed by assessment of position and vibration sense and by discriminatory sensation (Fig 5.4). Light touch is tested using a wisp of cotton wool, pain is tested by the response to pin prick and cortical sensory discrimination by the ability to differentiate between pressure from the pointed end and the blunt head of a pin. Temperature is tested by asking the patient to differentiate between tubes of warm and cold water. Areas of diminished sensation are mapped out and compared with the normal sensory dermatomes. The reproducibility of clinical findings should be checked. Variable results can occur due to ‘hysterical’ or factitious sensory loss or to loss of concentration — the patient’s tolerance and cooperation are particularly labile at extremes of pain, age and intellect. Glove-and-stocking loss of pain sensation in the lower limbs with normal motor function is typical of the peripheral neuropathy associated with diabetes. Deep sensation is tested by vibration and position sense; the former using a tuning fork applied to the medial malleolus and the latter by identifying the position of the moved great toe with the eyes closed.

3 Reflex function

The deep tendon reflex is dependent upon the integrity of the spinal reflex arc that consists of both afferent and efferent pathways. The induced reflex is an involuntary muscular response to a sensory stretch stimulus of the tendon. The upper motor neurone exerts an inhibiting effect on the reflex arc so that damage to this pathway leads to an increase in deep tendon reflexes. Chronic diminution or abolition of the reflex is nearly always associated with more distal disease and damage of the afferent (sensory) arc or of the efferent (lower motor) neurone. Reflexes are tested in the relaxed patient, alternately comparing sides as each tendon is put on the stretch and lightly struck with a rubber hammer. The spinal segments involved in the common stretch reflexes are the knee jerk (L 3 and 4), the ankle jerk (S1 and 2), the brachioradialis reflex and biceps jerk (C5 and 6), the triceps jerk (C6 and 7) and finger jerk (C 8) (Table 5.3). A reflex should not be considered to be absent until it is tested during reinforcement by contracting muscles other than those being tested (Jendrassik’s manoeuvre — the patient hooks the fingers of both hands together while pulling the fingers apart as the tendon reflex is elicited). Repeated muscle contractions (clonus) may be triggered by sudden and continued tendon stretching. Clonus is often found in patients with increased tendon reflexes resulting from a pyramidal lesion. The superficial plantar reflex is tested by stroking the lateral aspect of the sole of the foot. If the great toe extends rather than flexes, an upper motor neurone lesion of the pyramidal tract is present and the Babinski (extensor) response is present. Fanning of the other toes may also occur.

Table 5.3 The spinal segments involved in the common stretch reflexes

| Brachioradialis reflex and biceps jerk | C5, 6 |

| Triceps jerk | C6, 7 |

| Finger jerk | C8 |

| Knee jerk | L2, 3, 4 |

| Ankle jerk | S1, 2 |

5.3 Limb weakness and numbness — peripheral neuropathies

Weakness or paralysis of a limb, in whole or part, associated with wasting and with numbness or paraesthesia, suggests spinal neuronal disease, nerve root or plexus pathology, peripheral nerve lesion or neuropathy. Diagnosis of peripheral nerve disorders requires an accurate knowledge of the anatomic course of the major peripheral nerve trunks and their motor and sensory distributions.

Longstanding changes cause characteristic deformities and trophic changes that take weeks and months to develop. These are in marked contrast to the findings of acute nerve injury (Ch 13.10). Patients with chronic lesions learn to compensate for paralysed muscles by using alternative muscle groups (‘trick movements’). Testing the functions performed by individual muscles with a defined nerve of supply (‘bend the end joint of your index finger’), rather than testing complex purposeful movements involving many nerves and muscle groups (‘squeeze my hand’), is therefore vital in identifying specific nerve lesions.

Clinical assessment of specific nerve palsies

Nerve injuries have three degrees of severity.

Median nerve

Common causes

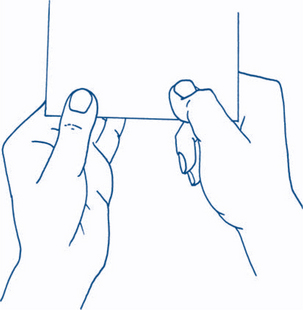

The ability of the patient to flex the end joint of the thumb and index finger against resistance (Fig 5.5) helps to determine that the level of median nerve involvement must be above the wrist — these muscles always being supplied by the median nerve — motor supply by the anterior interosseous nerve branch. A lesion in the forearm above the origin of the anterior interosseous nerve branch causes paralysis of these long flexors in addition to the two radial lumbricals. It also gives the sensory changes associated with a median nerve lesion. The deformity of the ‘pointing’ index and middle fingers, which are extended relative to the other fingers (signe de cardinal), and an inability to make the an ‘OK’ sign demonstrate the absence of tip–tip pinch with this nerve lesion.

Ulnar nerve

Common causes

Confirmation that the motor disability is due to an ulnar nerve lesion is given by the sensory loss over the ulnar aspect of the palmar and dorsal surfaces of hand and of the ulnar one and a half digits. The area of sensory loss always present in ulnar nerve injury is to the pulp of the little finger. With lesions at or below the level of the wrist joint, the sensation to the dorsal aspect of the ulnar one and a half digits is spared because the dorsal cutaneous branch of the ulnar nerve arises proximal to the wrist joint.

Additional tests of loss of motor function include:

Figure 5.6 Ulnar nerve lesion

The little finger is abducted away from the other fingers against resistance.

Lesions at the elbow or forearm. The ulnar nerve has no branches in the upper arm. Cubital tunnel syndrome is due to compression of the ulnar nerve in the vicinity of the elbow. Potential sites for compression include between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris, the arcade of Struthers, the fascia of Osborne (between the medial epicondyle and the olecranon), the fibres within the flexor carpi ulnaris and the anconeus muscle. As the ulnar nerve in the forearm supplies the flexor carpi ulnaris and the ulnar two tendons of the flexor digitorum profundus, involvement of these muscles indicates a lesion in or above the forearm.

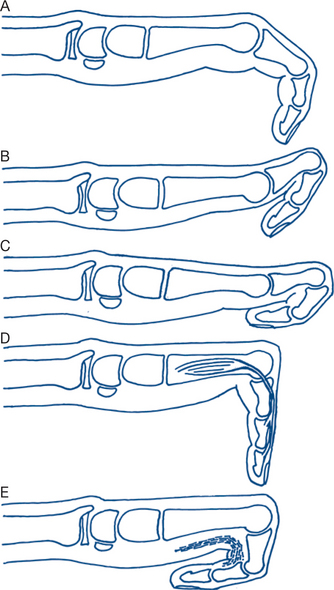

Combined median and ulnar palsies are usually due to an obvious wrist wound and result in a complete claw hand, with sensory loss affecting all five digits. Tendon injuries are commonly associated. It is always important to separate the effects of tendon and other injuries when assessing traumatic nerve palsies. Other causes of finger deformities are illustrated in Figure 5.8.

Axillary (circumflex) nerve

Common causes

Dislocation of the shoulder. The most common cause of axillary nerve palsy is anterior shoulder dislocation. Motor loss causes weakness or failure of arm abduction with atrophy of the cowl of the deltoid muscle, making the bony prominences of the shoulder more prominent. The deltoid is tested by palpating the muscle during isometric contraction or by abduction of the arm above the head, which cannot be performed with complete deltoid paralysis. Sensory loss involves a small patch over the lateral aspect of the shoulder.

Brachial plexus

Lower limb: common peroneal nerve

Common causes

The common peroneal nerve is rather superficial as it courses into the popliteal fossa. Furthermore, it is tethered at the neck of the fibula by deep fascia. Common peroneal nerve injury results in paralysis of the anterior and lateral compartment muscle groups, causing foot and toe drop. Extension of the great toe (EHL) is paralysed, as is eversion of the foot. Sensory loss occurs over the dorsum of the foot and toes with sparing on the medial and lateral sides; the loss extends up the anterolateral aspect of the lower leg half way to the knee.

Lumbo-sacral plexus and roots

5.4 Limb weakness — other causes

Weakness with wasting

Clinical features

5 Myopathy

Causes of myopathies should be sought and include:

CNS Lesions — hemiplegia

Common causes

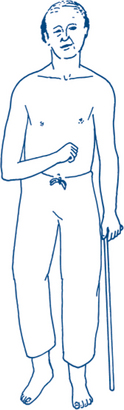

A typical constellation of physical signs usually enables the diagnosis of hemiplegia or hemiparesis to be made or suspected on sight. Features are as described below; refer also to Figure 5.9.

Diagnostic plan

Vascular stroke

Lesions in the territory of the internal carotid artery typically present with a triad of: hemiplegia or hemisensory deficit affecting of the opposite side of face, arm and leg; monocular visual loss (amaurosis fugax); and higher cortical dysfunction, such as dysphasia and visuospatial neglect. Amaurosis fugax is a temporary loss of vision or blurring that lasts a few seconds and usually clears over a few minutes. If vision fails to recover within 24 hours, this is analogous to a stroke. Extracranial carotid artery lesions may have prodromal transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) with ocular symptoms on the affected side, that is, amaurosis fugax and motor or sensory effects on the contralateral side. The symptoms usually resolve in 24 hours. Symptoms lasting over 24 hours are generally regarded as a stroke. A bruit may be present over the carotid bifurcation stenosis, although this is not a constant feature.

Spinal cord lesions — paraplegia or quadriplegia

Hemisection of the spinal cord (Brown-Séquard syndrome)

Other causes of paraplegia with dissociated sensory loss are: