7 Axillary Block

Traditional Block Technique

Placement

Anatomy

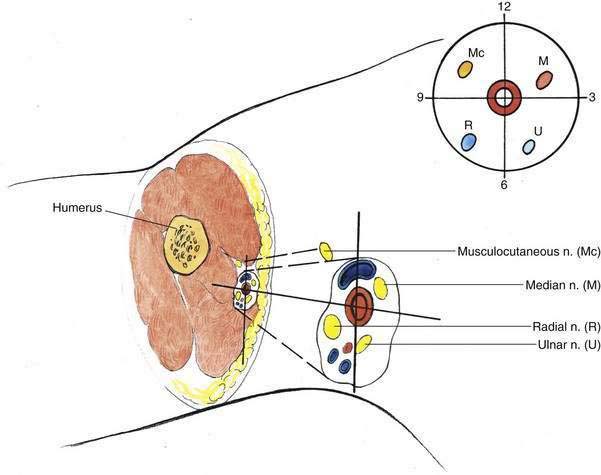

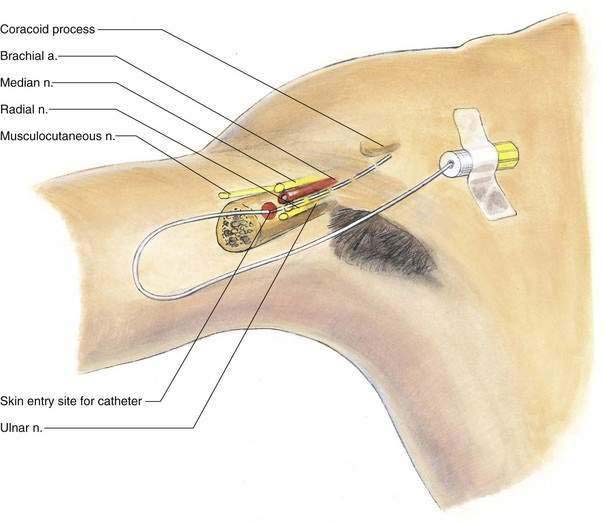

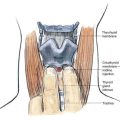

At the level of the distal axilla, where the axillary block is undertaken (Fig. 7-1), the axillary artery can be visualized as the center of a four-quadrant neurovascular bundle. I conceptualize these nerves in quadrants like a clock face because multiple injections during axillary block result in more acceptable clinical anesthesia than does injection at a single site. The musculocutaneous nerve is found in the 9- to 12-o’clock quadrant in the substance of the coracobrachialis muscle. The median nerve is most often found in the 12- to 3-o’clock quadrant; the ulnar nerve is “inferior” to the median nerve in the 3- to 6-o’clock quadrant; and the radial nerve is located in the 6- to 9-o’clock quadrant. The block does not need to be performed in the axilla; in fact, needle insertion in the middle to lower portion of the axillary hair patch or even more distal to this is effective. It is clear from radiographic and anatomic study of the brachial plexus and the axilla that separate and distinct sheaths are associated with the plexus at this point. Keeping this concept in mind will help to decrease the number of unacceptable blocks performed. Also, this more distal approach to axillary block is similar to the mid-humeral brachial plexus block.

Position

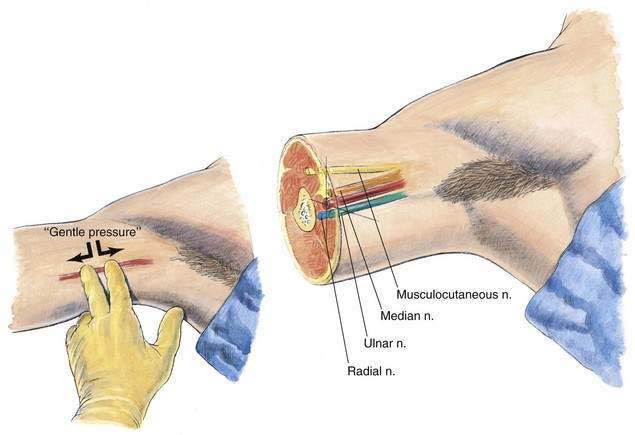

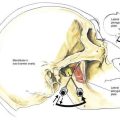

The patient is placed supine, with the arm forming a 90-degree angle with the trunk, and the forearm forming a 90-degree angle with the upper arm (Fig. 7-2). This position allows the anesthesiologist to stand at the level of the patient’s upper arm and palpate the axillary artery, as illustrated in Figure 7-2. A line should be drawn tracing the course of the artery from the mid-axilla to the lower axilla; overlying this line, the index and third fingers of the anesthesiologist’s left hand are used to identify the artery and minimize the amount of subcutaneous tissue overlying the neurovascular bundle. In this manner, the anesthesiologist can develop a sense of the longitudinal course of the artery, which is essential for performing an axillary block.

Needle Puncture

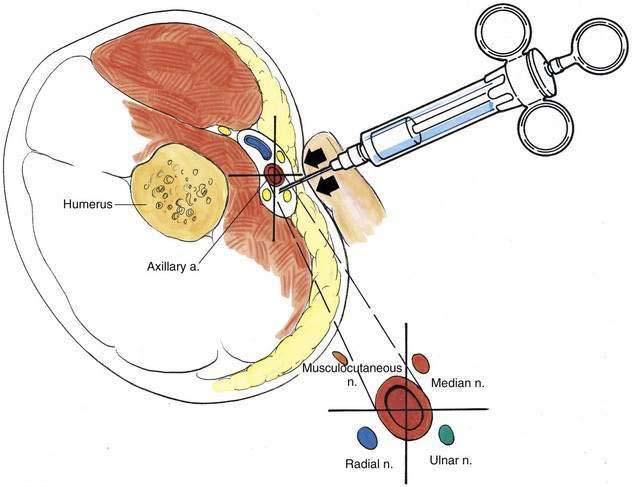

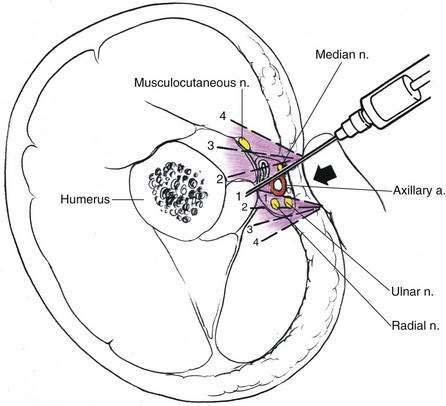

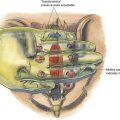

While the axillary artery is identified with two fingers, the needle and syringe are inserted as shown in Figure 7-3. Some local anesthetic should be deposited in each of the quadrants surrounding the axillary artery. If paresthesia is obtained it is beneficial, although undue time should not be expended or patient discomfort incurred from an attempt to elicit a paresthesia. As illustrated in Figure 7-4, effective axillary block is produced by using the axillary artery as an anatomic landmark and infiltrating in a fanlike manner around the artery. Anesthesia of the musculocutaneous nerve is best achieved by infiltrating into the mass of the coracobrachialis muscle. This maneuver can be carried out by identifying the coracobrachialis and injecting anesthetic into its substance, or by inserting a longer needle until it contacts the humerus and injecting in a fanlike manner near the humerus (see Fig. 7-4).

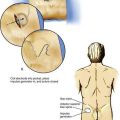

When using a continuous catheter technique for an axillary block, stimulating or nonstimulating catheter kits may be used; I prefer the stimulating catheter (Fig. 7-5). With the nonstimulating catheter, the epidural needle is positioned either with the assistance of a nerve stimulator or with elicitation of paresthesia as an end point. After the needle is positioned, 20 mL of preservative-free normal saline solution is injected through the needle, and then the appropriate-size catheter is inserted approximately 10 cm past the needle tip. Once the catheter has been secured with a plastic occlusive dressing, the initial bolus of drug is injected and the infusion is started.

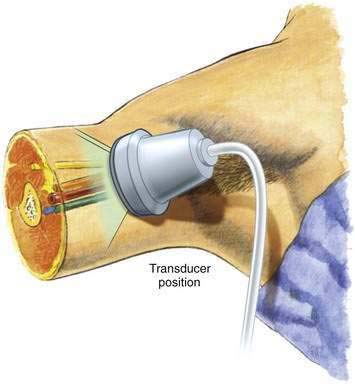

Ultrasonography-Guided Technique

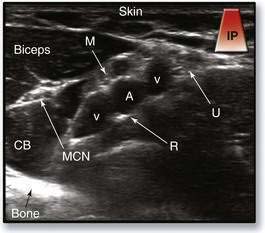

The operator should place the ultrasound transducer in the axilla perpendicular to the long axis of the neurovascular bundle (Fig. 7-6). The goal is to obtain an image with the axillary artery in the center as a pulsatile hypoechoic circle. Before needle insertion, the operator should attempt to identify the four major nerves of the brachial plexus at this level (Fig. 7-7). The musculocutaneous nerve may not be visualized in the same image with the other three nerves because it is often several centimeters anterior and lateral to the axillary artery; there is a high degree of variability in the axillary neurovascular structures.

To visually locate the musculocutaneous nerve, the operator should slide the transducer anterolaterally and locate the coracobrachialis muscle. The musculocutaneous nerve appears as a hyperechoic oval or circle lying between the coracobrachialis and biceps muscles (see Fig. 7-7). A separate needle insertion site is needed to block this nerve. The needle is advanced through the biceps muscle using the in-plane technique. We also use 5 to 8 mL of local anesthetic to block the musculocutaneous nerve identified by ultrasonography.