CHAPTER 35 Autologous contouring the lower face

Physical evaluation

1. Midface evaluation

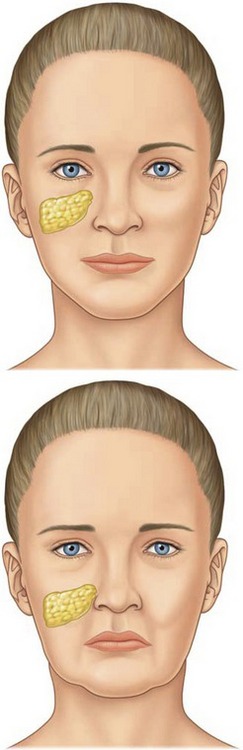

Malar fat pad

In a youthful midface, the superior border of the triangular shaped malar fat pad lies along the orbital rim and extends laterally to the zygomas (Fig. 35.1). The lateral border can be identified by drawing a line from the lateral canthus to the lateral commissure. The malar fat pad is located beneath the skin and subcutaneous fat, but it is superficial to the superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS). It is fibrous and fatty, and it is readily distinguishable from the overlying subcutaneous fat. With advancing age, the malar fat pad descends inferiorly and medially. Ptosis of the malar fat pad empties the midface and accentuates tear-trough and nasolabial folds. To a lesser extent, this displacement also results in the formation of labiomandibular folds (marionette lines) and jowls.

Nasolabial fold

The cutaneous insertion of the zygomaticus major/minor and levator labii superioris muscles determines the nasolabial fold. In a sense, the nasolabial fold may be considered a fasciocutaneous ligament necessary for lip elevating muscles to initiate a smile. Laxity of this fasciocutaneous ligament causes the malar fat pad to travel inferomedially over the crease to deepen the nasolabial fold.

2. Lip evaluation

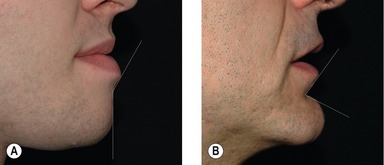

Labiomental fold

The position of the labiomental fold contributes to the appearance of the vertical height of the chin. A high labiomental fold will make the chin appear larger, and a low labiomental fold will make the chin appear smaller and more defined. A shallow or indistinct labiomental fold makes the chin appear larger because the demarcation between the lower lip and the chin pad is less well defined. The surgeon can also imagine the labiomental fold in profile as an angle (Fig. 35.2). A shallow fold has an obtuse angle and a deep fold has a more acute angle. Viewing the labiomental fold as an angle can be helpful when planning chin surgery. For example, performing an augmentation genioplasty on a patient with a low, deep labiomental fold will make the fold angle more acute and the fold will appear too deep.

3. Occlusion

Dental occlusion also affects the appearance of the lower-third of the face. For example, a deep bite may contribute to lower lip eversion with an oblique inclination as well as an acute angle at the labiomental fold. It is important to assess dental occlusion and inquire about prior orthodontic or orthognathic treatment. The treatment of patients with Angle Class II or Class III malocclusion is beyond the scope of this chapter.

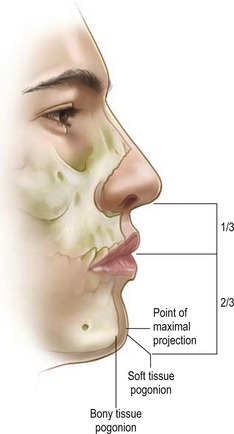

4. Chin evaluation

Chin pad thickness

The chin pad is assessed by palpation. Chin pad soft tissue projection should be maximally at the level of the pogonion (Fig. 35.3). Static chin pad position should be noted. A chin pad cleft represents a cleft in the mentalis muscle as well as a deficiency of the chin pad soft tissue.

Anatomy

The lower lip rolls outward creating an infralabial line of inclination (seen on profile) connecting the white roll to the labiomental fold. The labiomental fold is the point of greatest concavity and defines the superior extent of the chin pad. The mandibular symphyseal spine originates in the midline of the mandible beneath the labiomental fold. The symphyseal spine divides to enclose the mental protuberance. On either side of the symphysis, just below the mandibular incisors, are the incisive fossae. The incisive fossae provide origin for the mentalis muscle (Fig. 35.4). The mentalis muscles – so-named because of its association with the expressions of pondering and doubt – insert superiorly into the dermis to elevate and protrude the lower lip. The mentalis muscle can be divided into horizontal and oblique fibers. The division between these fibers defines the labiomental fold (Fig. 35.4). The labiomandibular crease is determined by the depressor anguli oris superiorly and the mandibular ligaments inferiorly, which then converts into a fold as a result of senile laxity of the masseteric ligaments. The mandibular retaining ligaments arise from the parasymphysial mandibular body and insert into the skin inferior to the insertion of the depressor anguli oris. The mandibular ligaments define the anterior extent of the jowls.

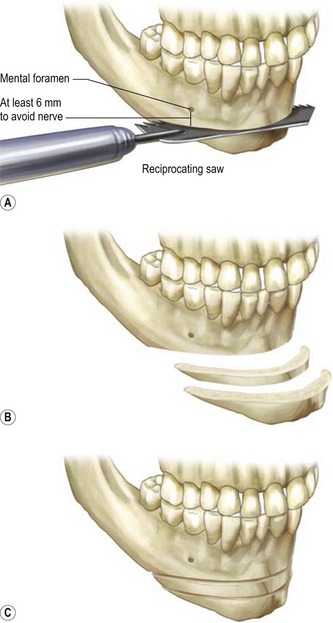

Technical steps

A 3 cm long intraoral incision is made 1 cm cephalad to the labiobuccal sulcus and electrocautery dissection is carried down through the subcutaneous tissues. The mentalis is divided and the periosteum is scored. Subperiosteal dissection is performed to expose the chin from mental nerve to mental nerve. The midline of the mandible is marked with a sagittal saw and the inclination of the osteotomy is decided. If the surgeon plans to perform a sliding genioplasty, the angle of the osteotomy will affect the vertical height of the chin as the genial segment is advanced sagittally. For example, an acute osteotomy slope angle (<70° relative to perpendicular line dropped from occlusal plane) will lead to a more vertical reduction for any given sagittal advancement. In contrast, an obtuse slope angle (>90°) will lead to a vertical elongation of the chin (Fig. 35.5). While a surgeon may choose a sliding genioplasty to advance and vertically reduce the chin, the change in sagittal advancement and vertical reduction is a fixed ratio based on the slope of the osteotomy. After the osteotomy angle is determined, the osteotomy is performed at least 6 mm below the mental foramina in order to avoid the intraosseous course of the inferior alveolar nerves.

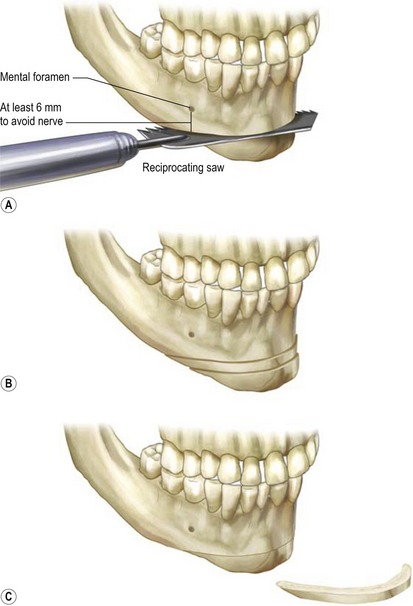

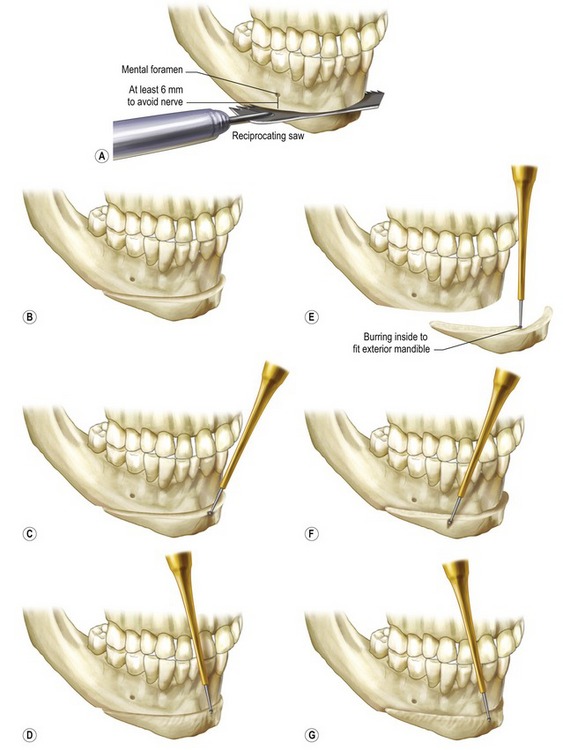

Fig. 35.5 Drawing of sliding genioplasty (left side) and jumping genioplasty (right side). A, The osteotomy angle is selected and the osteotomy is performed at least 6 mm below the mental formina in order to avoid the inferior alveolar nerves. B, The genial segment is advanced and fixed with a lag screw technique. C, The advanced genial segment is contoured with a burr as necessary to adjust sagittal projection and labiomental fold depth and angle. D, The advanced genial segment is contoured with a burr as necessary to adjust sagittal projection and labiomental fold depth and angle. E, Final contour adjustments are made on the sliding genioplasty. F, The genial segment is jumped on to the anterior surface of the mandible and fixed with a lag screw technique. The segment is then contoured with a burr as necessary to adjust sagittal projection and labiomental fold depth and angle. G, Final contour adjustments are made on the jumping genioplasty.

Once liberated, the bony segment is advanced anteriorly until the desired increase in sagittal projection is achieved. The attachments of the genioglossus, geniohyoid, anterior digastrics, and mylohyoid muscles to the posterior (labial) surface of the genial fragment are maintained to preserve the blood supply. An advancement of 5–7 mm is typical, but advancements of 10 mm are possible. If the surgeon is advancing the chin more than 10 mm, he should reconsider the maxillomandibular relationship as an orthognathic movement may be indicated.

Vertical elongation of the chin is usually achieved by interposition grafting (typically hydroxyapatite or bone graft) within the intercalary gap rather than choosing an obtuse osteotomy angle (Fig. 35.6). Conversely, if a reduction in the vertical height of the chin is necessary, a wafer of bone can be removed (Fig. 35.7). Chin asymmetry can be corrected shifting the osteotomized fragment laterally.

The genial segment can also be transposed or jumped to the anterior surface of the mandible. When performing a jumping genioplasty, a side cutting burr can be used to contour the posterior surface of the osteotomized segment in order to allow it to fit appropriately to the anterior surface of the mandible (Fig. 35.5). Contouring the posterior surface of the genial segment also enables the surgeon to control the amount of sagittal advancement.

Once in proper position, the osteotomized fragment is rigidly secured to the mandible using a lag technique with two or more countersunk screws (Fig. 35.5). It is important to note that the blood supply to the genial segment is provided through the genioglossus, geniohyoid, digastric, and mylohyoid muscles which originate along the mental spine, mental spine, digastric fossa, and mylohyoid line, respectively. The surgeon must preserve the muscular blood supply in order to avoid avascular necrosis of the genial segment.

Finally, the anterior surface of the secured genial segment is contoured using the side cutting burr to fine tune the desired pogonial sagittal projection and labiomental angle. When estimating the amount of desired sagittal advancement at the pogonion, we assume a 1 : 1 relationship between bony advancement and soft tissue change. A small drain can be passed transcutaneously through the submental skin. The gingivobuccal incision is closed with interrupted chromic sutures. Typical results are shown in Figs 35.8–35.10.

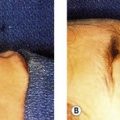

Fig. 35.8 21 year-old female presents with long non-projecting chin. The patient underwent an oblique osteotomy (~51° angle) of the chin (4 mm vertical reduction and 5 mm sagittal advancement) and a LeFort I (4 mm vertical reduction and 5 mm sagittal advancement) A. Preoperative frontal view. B. Postoperative frontal view at 6 months. C. Preoperative lateral view. D. Postoperative lateral view at 6 months.

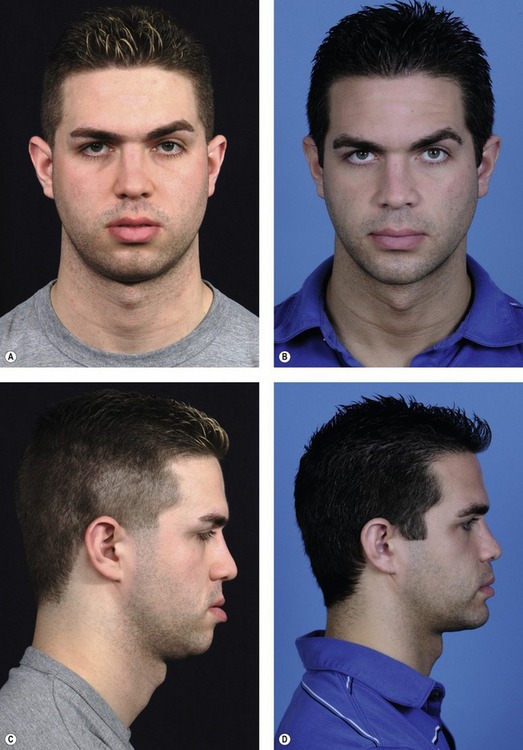

Fig. 35.9 25 year-old male presents with sagittally deficient chin, class III malocclusion, and lip incompetence. The patient underwent a horizontal osteotomy (~ 80° angle) of the chin (0 mm vertical change and 6 mm sagittal advancement) and LeFort I osteotomy (0 mm vertical change and 7 mm sagittal advancement). A. Preoperative frontal view. B. Postoperative frontal view at 1 year. C. Preoperative lateral view. D. Postoperative lateral view at 1 year.

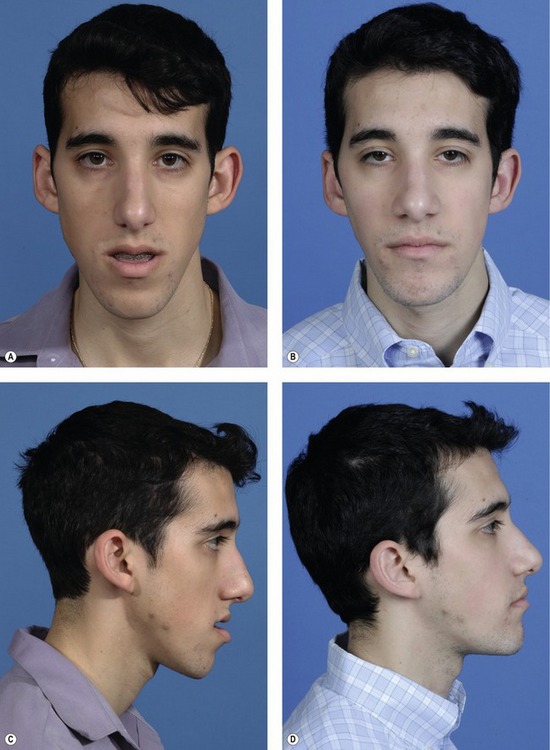

Fig. 35.10 24 year-old male presents with sagittally deficient and vertically long chin, class III malocclusion, and lip incompetence. The patient underwent an oblique osteotomy (~ 70° angle) of the chin (2 mm vertical change and 5 mm sagittal advancement), LeFort I osteotomy (3.5 mm vertical reduction and 8 mm sagittal advancement), and a bilateral sagittal split osteotomy of the mandible with counter-clockwise rotation. A. Preoperative frontal view. B. Postoperative frontal view at 18 months. C. Preoperative lateral view. D. Postoperative lateral view at 18 months.

Treatment of a large chin can also be performed through a similar approach. Reduction macrogenia can be performed with a side-cutting burr; however, we must caution the reader that burring can produce an unnatural, flattened appearance to the chin and soft tissue ptosis giving a double chin. Instead, we prefer to reduce a large chin using the osseous genioplasty approach described above except we make an effort to limit the subperiosteal dissection as much as possible so that as the osteotomized segment is set back, the overlying soft tissues are drawn with the segment. Since bony set-back or reduction moves the soft-tissue pogonion posteriorly, care must be taken not to overcorrect patients with a preoperative obtuse labiomental fold. Conversely, there is more leeway for bony reduction if the labiomental fold was deep preoperatively. After fixation of the genial fragment with wires, the segments lateral wings are smoothed by burring.

Complications

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• While correction of chin deformities is deceptively simple, inadequate planning will lead to an unsatisfactory result. A systematic evaluation of the lower third of the face is essential for diagnosing the chin problem and designing the correct operation to treat it.

• Gender is important. As a rule, women prefer a slightly less projecting, rounder chin while men tolerate a slightly more projecting, angular chin. Remember that the height of the chin pad as well as the location and depth of the labiomental fold will affect the appearance of the chin.

• Malocclusion (or a history of extensive orthodontics with compensated occlusion) is a clue that the patient may have more than a simple micro- or macrogenia. Careful assessment is necessary to document maxillary and/or mandibular micrognathia or prognathism, which may be better served by orthognathic surgery.

• Osseous genioplasty is an extremely versatile operation with many advantages. It can be performed on an outpatient basis through an intraoral or submental incision.

• A sliding genioplasty brings the osteotomies segment anteriorly and superiorly at a fixed ratio based on the osteotomy angle. Additional degrees of freedom can be obtained by using a jumping genioplasty.

• Reduction genioplasty is every bit as difficult as augmentation genioplasty. It is preferable to limit the subperiosteal dissection, perform an osteotomy and retroposition both the bony chin and soft tissues.

Pitfalls

• When assessing the lower-third of the face, avoid the tendency to look only at the chin. The appearance of the lower-third of the face is dependent on the gender as well as facial structure. Components of the lower third of the face include the nose, nasolabial folds, lips, labiomental sulcus, labiomandibular crease, chin pad, and bony chin.

• Avoid the mental nerves as they pass inferior and mesial to the mental foramina. Remember that the canine roots may extend as much as 28 mm below the incisal edge.

• Whether performing a sliding or jumping genioplasty, preserve the blood supply to the genial segment in order to avoid avascular necrosis. Remember that the genioglossus, geniohyoid, anterior digastric, and mylohyoid muscles provide the blood supply to the osteotomized segment.

• Burring of the chin is often an inappropriate technical choice for chin reduction. In most cases, it results in a flattened appearance and soft tissue ptosis. Instead, osteotomize the chin and retroposition the bony segment. Limit the subperiosteal dissection in order to preserve soft tissues contact with the bony segment. Perform submental skin and soft tissue excision where appropriate to eliminate submental fullness.

Summary of steps

1. Perform a systematic preoperative assessment of the lower third of the face. Consider the perialar projection, the nasolabial fold, the labial relationship, the dental relationship, the position and depth of the labiomental fold, the vertical chin height, the thickness of the soft-tissue chin pad, and the size, shape, symmetry of the bony chin in the context of the patient’s gender and facial structure.

2. Use general anesthesia, the soft tissues should be injected with 1% lidocaine with epinephrine. Make an intraoral incision and perform subperiosteal dissection from bicuspid to bicuspid and along the lower border of the mandible.

3. Score a vertical line in the mandibular symphysis. If a sliding genioplasty is to be performed, the inclination of the osteotomy is decided upon in order to provide the correct sagittal and superior advancement.

4. Perform the osteotomy at least 6 mm below the mental foramina in order to protect the mental nerves.

5. Slide or jump the osteotomized genial segment anteriorly.

6. If the chin is to be reduced, move the osteotomized genial segment superiorly and/or posteriorly rather than burring the pogonion.

7. Fix the genial segment using a lag screw technique. Perform in situ contouring to adjust the sagittal projection.

8. Close the mucosal incision with interrupted sutures and apply a light compressive dressing. If necessary, bring out a drain beneath the menton.

9. The drain is removed in 24 hours and the dressing is removed in 4 days.

McCarthy JG, Ruff GL, Zide BM. A surgical system for the correction of bony chin deformity. Clin Plast Surg. 1991;18(1):139–152.

McCarthy JG, Ruff GL. The chin. Clin Plast Surg. 1988;15(1):125–137.

McCarthy JG. Plastic surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1990.

McCarthy JG. Microgenia: a logical surgical approach. Clin Plast Surg. 1981;8(2):269–278.

Ward JL, Garri JI, Wolfe SA. The osseous genioplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2007;34(3):485–500.

Zide B, Grayson B, McCarthy JG. Cephalometric analysis for mandibular surgery: Part III. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69(1):155–164.

Zide B, Grayson B, McCarthy JG. Cephalometric analysis for upper and lower midface surgery: Part II. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981;68(6):961–968.

Zide B, Grayson B, McCarthy JG. Cephalometric analysis: Part I. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981;68(5):816–822.