Chapter 354 Autoimmune Hepatitis

Chronic hepatitis can also be caused by persistent viral infection (Chapter 350), drugs (Chapter 355), metabolic diseases (Chapter 353), or unknown and autoimmune disorders (Table 354-1). Approximately 15-20% of chronic cases are associated with hepatitis B infection; unusually severe disease may be caused by superimposed infection with hepatitis D (a defective RNA virus that is dependent on replicating hepatitis B virus [HBV]). More than 90% of hepatitis B infections in the 1st yr of life become chronic, compared with 5-10% among older children and adults. Chronic hepatitis develops in >50% of acute hepatitis C virus infections. Patients receiving blood products or who have had massive transfusions are at increased risk. Hepatitis A or E viruses do not cause chronic hepatitis. Drugs that are commonly used in children and can cause chronic liver injury include isoniazid, methyldopa, pemoline, nitrofurantoin, dantrolene, minocycline, pemoline, and the sulfonamides. Metabolic diseases can lead to chronic hepatitis including α1-antitrypsin deficiency, inborn errors of bile acid biosynthesis, and Wilson disease. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, usually associated with obesity and insulin resistance, is another common cause of chronic hepatitis; it is relatively benign and responds to weight reduction and/or vitamin E therapy. Progression to cirrhosis has been described in adults and some children. In most cases, the cause of chronic hepatitis is unknown; in many, an autoimmune mechanism is suggested by the finding of serum antinuclear and anti–smooth muscle antibodies and by multisystem involvement (arthropathy, thyroiditis, rashes, Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia).

Autoimmune hepatitis is a clinical constellation that suggests an immune-mediated process; it is responsive to immunosuppressive therapy (Table 354-2). Autoimmune hepatitis typically refers to a primarily hepatocyte-specific process, whereas autoimmune cholangiopathy and sclerosing cholangitis are predominated by intra- and extrahepatic bile duct injury. Overlap of the process involving both hepatocyte and bile duct directed injury may be common in children. De novo hepatitis is seen in a subset of liver transplant recipients whose initial disease was not autoimmune.

Table 354-2 CLASSIFICATION OF AUTOIMMUNE HEPATITIS

| VARIABLE | TYPE 1 AUTOIMMUNE HEPATITIS | TYPE 2 AUTOIMMUNE HEPATITIS |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic autoantibodies | Antinuclear antibody* | Antibody against liver-kidney microsome 1* |

| Smooth-muscle antibody* | ||

| Antiactin antibody† | Antibody against liver cytosol 1* | |

| Autoantibodies against soluble liver antigen and liver-pancreas antigen‡ | ||

| Atypical perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody | ||

| Geographic variation | Worldwide | Worldwide; rare in North America |

| Age at presentation | Any age | Predominantly childhood and young adulthood |

| Sex of patients | Female in ~75% of cases | Female in ~95% of cases |

| Association with other autoimmune diseases | Common | Common§ |

| Clinical severity | Broad range | Generally severe |

| Histopathologic features at presentation | Broad range | Generally advanced |

| Treatment failure | Infrequent | Frequent |

| Relapse after drug withdrawal | Variable | Common |

| Need for long-term maintenance | Variable | ~100% |

* The conventional method of detection is immunofluorescence.

† Tests for this antibody are rarely available in commercial laboratories.

‡ This antibody is detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

§ Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy is seen only in patients with type 2 disease.

From Krawitt EL: Autoimmune hepatitis, N Engl J Med 354:54–66, 2006.

Laboratory Findings

Most patients with autoimmune hepatitis have hypergammaglobulinemia. Serum immunoglobulin (Ig) G levels usually exceed 16 g/L. Characteristic patterns of serum autoantibodies define several subgroups of autoimmune hepatitis (see Table 354-2). The most common pattern is the formation of non–organ-specific antibodies, such as antiactin (smooth muscle) and antinuclear antibodies. Approximately 50% of these patients are 10-20 yr of age. High titers of a liver-kidney microsomal (LKM) antibody are detected in another form that usually affects children 2-14 yr of age. A subgroup of primarily young women might demonstrate autoantibodies against a soluble liver antigen but not against nuclear or microsomal proteins. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies may be seen more commonly in autoimmune cholangiopathy. Autoantibodies are rare in healthy children so that titers as low as 1 : 40 may be significant, although nonspecific elevation in autoantibodies can be observed in a variety of liver diseases. Up to 20% of patients with apparent autoimmune hepatitis might not have autoantibodies at presentation. Antibodies to a cytochrome P450 component of LKM are commonly found in adult patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Homologies in antigenic peptide epitopes between the hepatitis C virus and cytochrome P450 might explain this. Other, less-common autoantibodies include rheumatoid factor, anti-parietal cell antibodies, and antithyroid antibodies. A Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia may be present.

Diagnosis

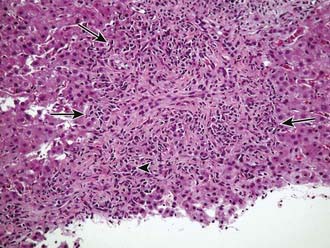

Autoimmune hepatitis is a clinical diagnosis based on certain diagnostic criteria; no single test will make this diagnosis. Diagnostic criteria with scoring systems have been developed for adults and modified slightly for children, although these scoring systems were developed as research and not diagnostic tools. Important positive features include female gender, primary elevation in transaminases and not ALP, elevated gamma-globulin levels, the presence of autoantibodies (most commonly antinuclear, smooth muscle, or liver-kidney microsome), and characteristic histologic findings (Fig. 354-1). Important negative features include the absence of viral markers (hepatitis B, C, D) of infection, absence of a history of drug or blood product exposure, and negligible alcohol consumption.

All other conditions that might lead to chronic hepatitis should be excluded (see Table 354-1). The differential diagnosis includes α1-antitrypsin deficiency (Chapter 349) and Wilson disease (Chapter 349.2). The former disorder must be excluded by performing α1-antitrypsin phenotyping and the latter by measuring serum ceruloplasmin and 24 hr urinary copper excretion and/or hepatic copper levels. Chronic hepatitis may occur in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, but liver dysfunction in such patients is more commonly due to pericholangitis or sclerosing cholangitis. Celiac disease (Chapter 330.2) is associated with liver disease that is akin to autoimmune hepatitis, and appropriate serologic testing should be performed, including assays for tissue transglutaminase. An ultrasonogram should be done to identify a choledochal cyst or other structural disorders of the biliary system. MR cholangiography may be very useful for screening for evidence of sclerosing cholangitis. Dilated or obliterated veins on ultrasonography suggest the possibility of the Budd-Chiari syndrome.

Prognosis

Orthotopic liver transplantation has been successful in patients with end-stage liver disease associated with autoimmune hepatitis (Chapter 360). Disease can recur after transplantation. Indication for transplantation should include evidence of hepatic decompensation.

Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929-938.

Corte CD, Ranucci G, Tufano M, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis type 2 arising in PFAPA syndrome: coincidences or possible correlations? Pediatrics. 2010;125:e683-e686.

Czaja AJ, Bianchi FB, Carpenter HA, et al. Treatment challenges and investigational opportunities in autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2005;41:207-215.

Czaja AJ. Autoimmune hepatitis. Part A: pathogenesis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;1:113-128.

Decock S, McGee P, Hirschfield GM. Autoimmune liver disease for the non-specialist. BMJ. 2009;339:686-691.

Ferreira AR, Roquete ML, Toppa NH, et al. Effect of treatment of hepatic histopathology in children and adolescents with autoimmune hepatitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:65-70.

Gregorio GV, Portmann B, Reid F, et al. Autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome in childhood: A 16 year prospective study. Hepatology. 2001;33:544-553.

Krawitt EL. Autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:54-66.

Lankisch TO, Mourier O, Sokal EM, et al. AIRE gene analysis in children with autoimmune hepatitis type I or II. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:498-500.

Oettinger R, Brunnberg A, Gerner P, et al. Clinical features and biochemical data of Caucasian children at diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Autoimmun. 2005;24:79-84.

Rumbo C, Emerick KM, Emre S, et al. Azathioprine metabolite measurements in the treatment of autoimmune hepatitis in pediatric patients: A preliminary report. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35:391-398.

Vergani D, Mieli-Vergani G. Aetiopathogenesis of autoimmune hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3306-3312.