Chapter 30 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common neurobehavioral disorder of childhood, among the most prevalent chronic health conditions affecting school-aged children, and the most extensively studied mental disorder of childhood. ADHD is characterized by inattention, including increased distractibility and difficulty sustaining attention; poor impulse control and decreased self-inhibitory capacity; and motor overactivity and motor restlessness (Table 30-1). Definitions vary in different countries (Table 30-2). Affected children commonly experience academic underachievement, problems with interpersonal relationships with family members and peers, and low self-esteem. ADHD often co-occurs with other emotional, behavioral, language, and learning disorders (Table 30-3).

Table 30-1 DSM-IV DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR ATTENTION-DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER

CODE BASED ON TYPE

Reprinted with permission from American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association. Copyright 2000 American Psychiatric Association.

Table 30-2 DIFFERENCES BETWEEN U.S. AND EUROPEAN CRITERIA FOR ADHD OR HKD

| DSM-IV ADHD | ICD-10 HKD |

|---|---|

| SYMPTOMS | |

| Either or both of following: | All of following: |

| PERVASIVENESS | |

| Some impairment from symptoms is present in >1 setting | Criteria are met for >1 setting |

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition; HKD, hyperkinetic disorder; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition.

From Biederman J, Faraone S: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, Lancet 366:237–248, 2005.

Table 30-3 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF ATTENTION-DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER

PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS

DIAGNOSES ASSOCIATED WITH ADHD BEHAVIORS

MEDICAL AND NEUROLOGIC CONDITIONS

Note: Coexisting conditions with possible ADHD presentation include oppositional defiant disorder, anxiety disorders, conduct disorder, depressive disorders, learning disorders, and language disorders. Presence of one or more of the symptoms of these disorders can fall within the spectrum of normal behavior, whereas a range of these symptoms may be problematic but fall short of meeting the full criteria for the disorder.

From Reiff MI, Stein MT: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder evaluation and diagnosis: a practical approach in office practice, Pediatr Clin North Am 50:1019–1048, 2003. Adapted from Reiff MI: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders. In Bergman AB, editor: 20 Common problems in pediatrics, New York, 2001, McGraw-Hill, p 273.

Epidemiology

Studies of the prevalence of ADHD across the globe have generally reported that 5-10% of school-aged children are affected, although rates vary considerably by country, perhaps in part due to differing sampling and testing techniques. Rates may be higher if symptoms (inattention, impulsivity, hyperactivity) are considered in the absence of functional impairment. The prevalence rate in adolescent samples is 2-6%. Approximately 2% of adults have ADHD. ADHD is often underdiagnosed in children and adolescents. Youth with ADHD are often undertreated with respect to what is known about the needed and appropriate doses of medications. Many children with ADHD also present with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, including opposition defiant disorder, conduct disorder, learning disabilities, and anxiety disorders (see Table 30-3).

Clinical Manifestations

Development of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) criteria leading to the diagnosis of ADHD has occurred mainly in field trials with children 5-12 yr of age (see Table 30-1). The current DSM-IV criteria state that the behavior must be developmentally inappropriate (substantially different from that of other children of the same age and developmental level), must begin before age 7 yr, must be present for at least 6 mo, must be present in 2 or more settings, and must not be secondary to another disorder. DSM-IV identifies 3 subtypes of ADHD. The 1st subtype, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, predominantly inattentive type, often includes cognitive impairment and is more common in females. The other 2 subtypes, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type, and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, combined type, are more commonly diagnosed in males. Clinical manifestations of ADHD may change with age. The symptoms may vary from motor restlessness and aggressive and disruptive behavior, which are common in preschool children, to disorganized, distractible, and inattentive symptoms, which are more typical in older adolescents and adults. ADHD is often difficult to diagnose in preschoolers because distractibility and inattention are often considered developmental norms during this period.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Chronic illnesses, such as migraine headaches, absence seizures, asthma and allergies, hematologic disorders, diabetes, childhood cancer, affect up to 20% of children in the U.S. and can impair children’s attention and school performance, either because of the disease itself or because of the medications used to treat or control the underlying illness (medications for asthma, steroids, anticonvulsants, antihistamines) (see Table 30-3). In older children and adolescents, substance abuse (Chapter 108) can result in declining school performance and inattentive behavior.

Sleep disorders, including those secondary to chronic upper airway obstruction from enlarged tonsils and adenoids, often result in behavioral and emotional symptoms, although such problems are not likely to be principal contributing causes of ADHD (Chapter 17). Behavioral and emotional disorders can cause disrupted sleep patterns.

Depression and anxiety disorders (Chapters 23 and 24) can cause many of the same symptoms as ADHD (inattention, restlessness, inability to focus and concentrate on work, poor organization, forgetfulness), but can also be comorbid conditions. Obsessive-compulsive disorder can mimic ADHD, particularly when recurrent and persistent thoughts, impulses, or images are intrusive and interfere with normal daily activities. Adjustment disorders secondary to major life stresses (death of a close family member, parents’ divorce, family violence, parents’ substance abuse, a move) or parent-child relationship disorders involving conflicts over discipline, overt child abuse and/or neglect, or overprotection can result in symptoms similar to those of ADHD.

Although ADHD is believed to result from primary impairment of attention, impulse control, and motor activity, there is a high prevalence of comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders (see Table 30-3). Of children with ADHD, 15-25% have learning disabilities, 30-35% have language disorders, 15-20% have diagnosed mood disorders, and 20-25% have coexisting anxiety disorders. Children with ADHD can also have co-occurring diagnoses of sleep disorders, memory impairment, and decreased motor skills.

Treatment

Medications

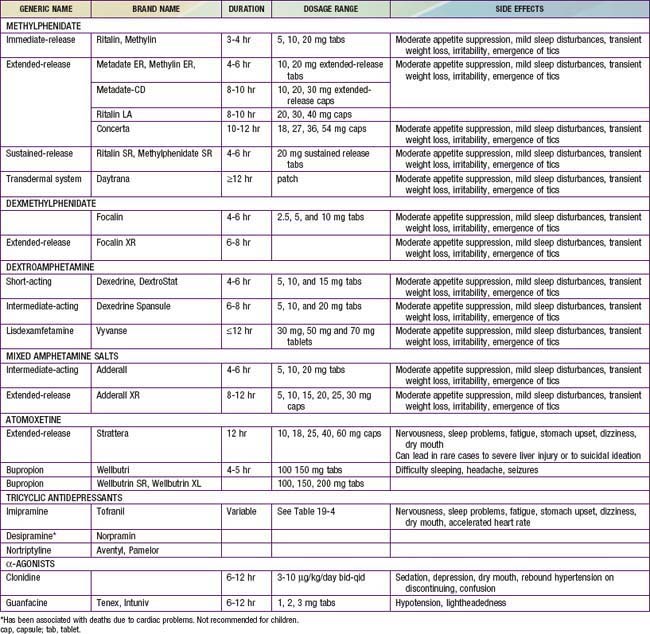

The most widely used medications for the treatment of ADHD are the psychostimulant medications, including methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta, Metadate, Focalin, Daytrana), amphetamine, and/or various amphetamine and dextroamphetamine preparations (Dexedrine, Adderall, Vyvanse) (Table 30-4). Longer-acting, once-daily forms of each of the major types of stimulant medications are available and facilitate compliance with treatment. The clinician should prescribe a stimulant treatment, either methylphenidate or an amphetamine compound. If a full range of methylphenidate dosages is used, approximately 25% of patients have an optimal response on a low (<20 mg/day), medium (20-50 mg/day), or high (>50 mg/day) daily dosage; another 25% will be unresponsive or will have side effects, making that drug particularly unpalatable for the family.

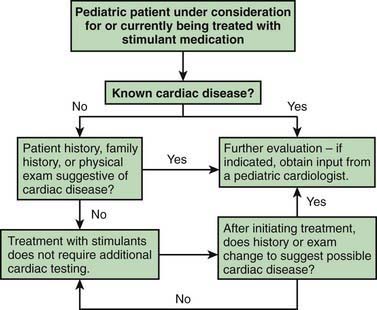

Stimulant drugs used to treat ADHD may be associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events, including sudden cardiac death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in young adults and rarely in children. In some of the reported cases, the patient had an underlying disorder, such as hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, which is made worse by sympathomimetic agents. These events are rare, but they nonetheless warrant consideration before initiating treatment and during monitoring of treatment with stimulant medications. Children with a positive or personal family history of cardiomyopathy, or arrhythmias, or syncope will require an electrocardiogram and possible cardiology consultation before a stimulant is prescribed (Fig. 30-1).

American Academy of Pediatrics/American Heart Association. American Academy of Pediatrics/American Heart Association clarification of statement on cardiovascular evaluation and monitoring of children and adolescents with heart disease receiving medications for ADHD: May 16, 2008. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29(4):335.

Atkinson M, Hollis C. NICE guideline: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2010;95:24-27.

Babcock T, Ornstein CS. Comorbidity and its impact in adult patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a primary care perspective. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:73-82.

Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, et al. Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: Adaptive functioning in major life activities. J Am Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:192-202.

Bouchard MF, Bellinger DC, Wright RO, et al. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and urinary metabolites of organophosphate pesticides. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1270-e1277.

Brookes KJ, Mill J, Guindalini C, et al. A common haplotype of the dopamine transporter gene associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and interacting with maternal use of alcohol during pregnancy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:74-81.

Caspi A, Langley K, Milne B, et al. A replicated molecular genetic basis for subtyping antisocial behavior in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:203-210.

Eigenmann PA, Haenggeli CA. Food colourings, preservatives, and hyperactivity. Lancet. 2007;370:1524-1525.

Gould MS, Walsh BT, Munfakh JL, et al. Sudden death and use of stimulant medications in youths. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:992-1101.

Greenhill L, Kollins S, Abikoff H, et al. Efficacy and safety of immediate-release methylphenidate treatment for preschoolers with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:1284-1293.

Hammerness P, Wilens T, Mick E, et al. Cardiovascular effects of longer-term, high-dose OROS methylphenidate in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Pediatr. 2009;155:84-89.

Harpin VA. Medication options when treating children and adolescents with ADHA: interpreting the NICE guidance 2006. Arch Dis Child Pract Ed. 2008;93:58-66.

Jones K, Daley D, Hutchings J, et al. Efficacy of the Incredible Years Programme as an early intervention for children with conduct problems and ADHD: long-term follow-up. Child Care Health Dev. 2008;34:380-390.

Kendall T, Taylor E, Perez A, et al. Diagnosis and management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children, young people, and adults: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:751-754.

Knight M. Stimulant-drug therapy for attention-deficit disorder (with or without hyperactivity) and sudden cardiac death. Pediatrics. 2007;119:154-155.

Kollins S, Greenhill L, Swanson J, et al. Rationale, design, and methods of the preschool ADHA treatment study (PATS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:1275-1283.

Langberg JM, Brinkman WB, Lichtenstein PK, et al. Interventions to promote the evidence-based care of children with ADHD in primary-care settings. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:477-487.

McCann D, Barrett A, Cooper A, et al. Food additives and hyperactive behaviour in 3-year-old and 8/9-year-old children in the community: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1560-1567.

2010 The Medical Letter: Guanfacine extended-release (Intuniv) for ADHD. Med Lett. 2010;52:82.

Mosholder AD, Gelperin K, Hammad TA, et al. Hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms associated with the use of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder drugs in children. Pediatrics. 2009;123:611-616.

Newcorn JH. Managing ADHD and comorbidities in adults. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(2):e40.

Newcorn JH, Kratochvil CJ, Allen AJ, et al. Atomoxetine and osmotically released methylphenidate for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: acute comparison and differential response. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:721-730.

Newcorn JH, Sutton VK, Weiss MD, et al. Clinical responses to atomoxetine in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the integrated data exploratory analysis (IDEA) study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:511-518.

Nutt DJ, Fone K, Asherson P, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adolescents in transition to adult services and in adults: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21:10-41.

Okie S. ADHD in adults. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2637-2641.

Pelsser LM, Frankena K, Toorman J, et al. Effects of restricted elimination diet on the behaviour of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (INCA study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:494-503.

Perrin JM, Friedman RA, Knilans TK. Cardiovascular monitoring and stimulant drugs for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2008;122:451-453.

Safren SA, Sprich S, Mimiaga MJ, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs relaxation with educational support for medication—adults with ADHD and persistent symptoms. JAMA. 2010;304:875-880.

Shum SBM, Pang MYC. Children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder have impaired balance function: involvement of somatosensory, visual, and vestibular systems. J Pediatr. 2009;155:245-249.

Silk TJ, Vance A, Rinehart N, et al. Dysfunction in the fronto-parietal network in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): an fMRI study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2008;2:1931.

Smith AK, Mick E, Faraone SV. Advances in genetic studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11:143-148.

Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Welcome SE, et al. Cortical abnormalities in children and adolescents with attention-deficit disorder. Lancet. 2008;362:1699-1707.

Spencer TJ. ADHD and comorbidity in childhood. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(supp 8):27-31.

Thomas PE, Carlo WE, Decker JA, et al. Impact of the American Heart Association scientific statement on screening electrocardiograms and stimulant medications. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(2):166-170.

Wilens TE, Prince JB, Spencer TJ, et al. Stimulants and sudden death: what is a physician to do? Pediatrics. 2006;118:1215-1219.

Zwi M, Clamp P. Injury and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. BMJ. 2008;337:1179-1180.