21 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Clinical Presentation

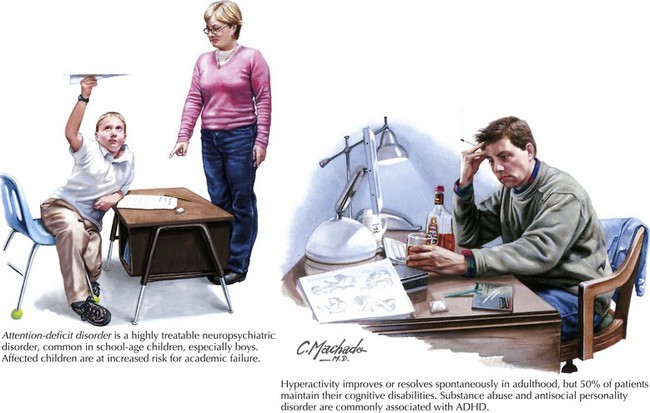

This occurs in 3–9% of school-age children; it has a definite genetic predisposition. Although some researchers find a higher prevalence of ADHD in boys than girls, other investigators dispute this, claiming that the sex disparity is an artifact of the more manifest behavioral disturbance and hyperactivity in boys (Fig. 21-1).

Barkley R. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford; 2005.

Bush G, Valera EM, Seidman LJ. Functional neuroimaging of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a review and suggested future directions. Biol Psychiatry. 2005 Jun 1;57(11):1273-1284.

Ellison-Wright I, Ellison-Wright Z, Bullmore E. Structural brain change in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder identified by meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2008 Jun 30;8:51.

Faraone SV, Wilens TE. Effect of stimulant medications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on later substance use and the potential for stimulant misuse, abuse, and diversion. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl. 11):15-22.

Garrett A, Penniman L, Epstein JN, et al. Neuroanatomical abnormalities in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008 Nov;47(11):1321-1328.

Hallowell EM, Ratey JJ. Driven to Distraction: Recognizing and Coping With Attention Deficit Disorder from Childhood through Adulthood. New York, NY: Touchstone; 1995.