38 Asthma

Etiology and Pathogenesis

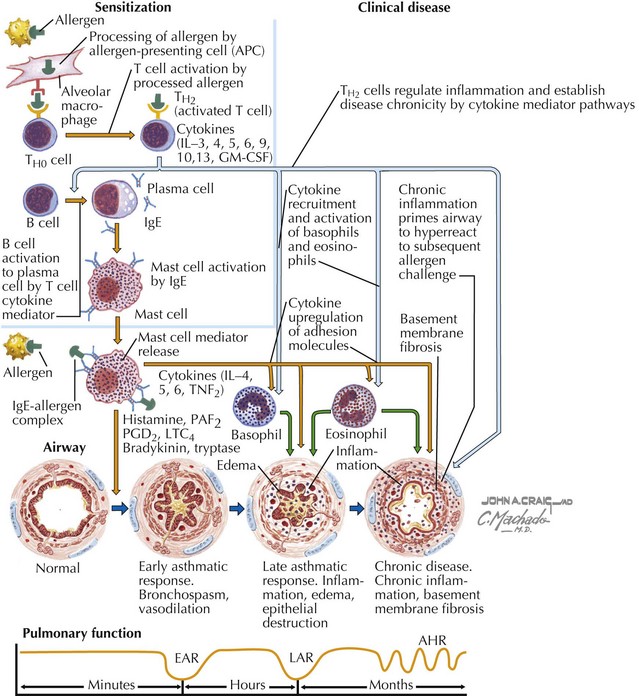

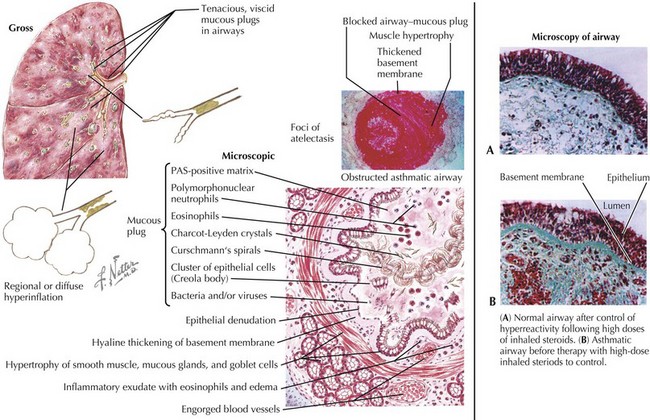

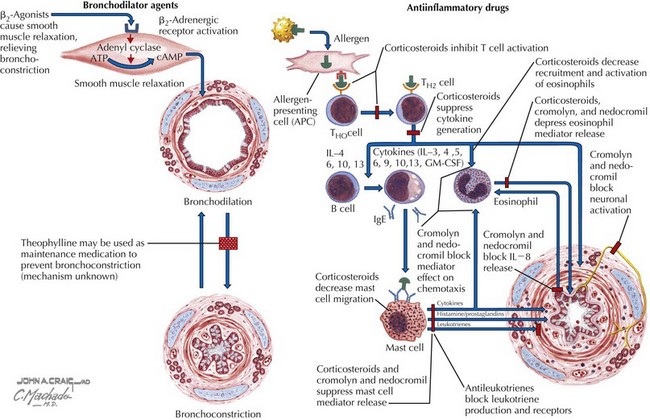

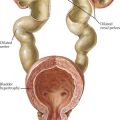

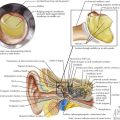

Asthma is characterized by the presence of three airway components: inflammation, obstruction, and hyperresponsiveness. Chronic airway inflammation establishes baseline airway edema and obstruction, which sets the stage for acute exacerbations. During acute exacerbations, inciting triggers (Box 38-1) cause inflammation and bronchoconstriction of already hyperresponsive airways. Key cellular components involved in the pathogenesis of asthma include mast cells; eosinophils; and, to some degree, neutrophils, T cells, macrophages, and epithelial cells (Figures 38-1 and 38-2).

Clinical Presentation

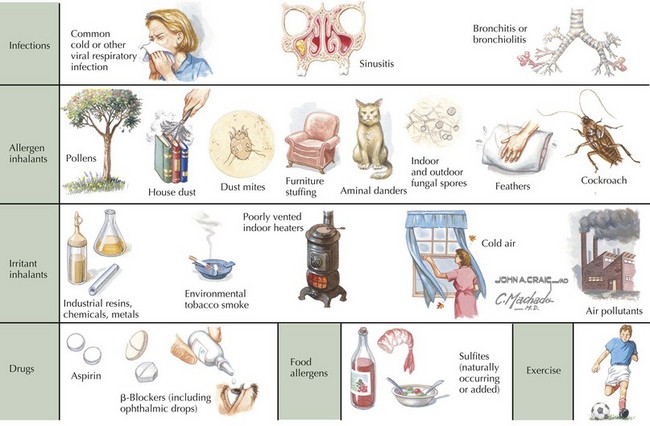

A patient or family history of allergy and atopic skin disease may be present. It is important to inquire about the setting(s) in which symptoms occur because a variety of inciting triggers exist (Box 38-1 and Figure 38-3). A patient should also be assessed for comorbid medical conditions, including GER, allergic rhinitis, sinusitis, and obesity, all of which can exacerbate asthma symptoms. For a patient with a previous asthma diagnosis, it is useful to inquire about the frequency of ED visits and hospital admissions, oral steroid use, and any history of severe complications (e.g., endotracheal intubation or admission to the intensive care unit [ICU]).

Differential Diagnosis

If considering a diagnosis of asthma, the time-worn axiom must be remembered that “all that wheezes is not asthma.” Before a diagnosis of asthma can be confirmed, alternative diagnoses must be considered (Table 38-1). Furthermore, not all wheezes are equal. For example, monophonic wheezing associated with foreign body aspiration is distinct from polyphonic wheezing associated with asthma.

| Differential Diagnosis | Suggested Confirmatory Tests | |

|---|---|---|

| Upper airway diseases | Allergic rhinitis or sinusitis | Physical examination, sinus CT scan |

| Obstruction of large airways | Foreign body in trachea or bronchus Vocal cord dysfunction Vascular rings or laryngeal webs Tracheomalacia Tracheal- or bronchostenosis Enlarged lymph nodes or tumor |

Chest radiography Laryngoscopy Barium swallow, chest MRI Laryngoscopy, flexible bronchoscopy Chest radiography, chest CT scan, bronchoscopy Chest radiography, chest CT scan |

| Obstruction of small airways | Viral bronchiolitis Bronchiolitis obliterans Cystic fibrosis Bronchopulmonary dysplasia Heart disease |

History, chest radiography, viral antigen or PCR testing Chest CT scan, lung biopsy Chest radiograph, sweat chloride test, genetic test Prenatal history, chest radiography, chest CT scan Chest radiograph, ECG, echocardiography |

| Other causes | Gastroesophageal reflux Oromotor dysfunction leading to chronic aspiration Pulmonary edema Tracheoesophageal fistula |

pH probe, barium swallow, nuclear milk scan Modified barium swallow, speech pathology evaluation Chest radiography Chest radiography, fluoroscopy, chest CT |

CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Adapted from the Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Washington, DC, U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources, 2007, p 12. Available at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm.

Evaluation

Chronic Disease

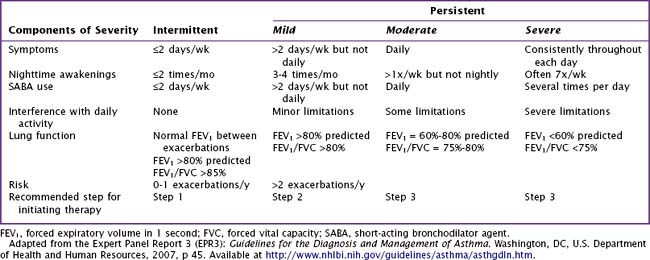

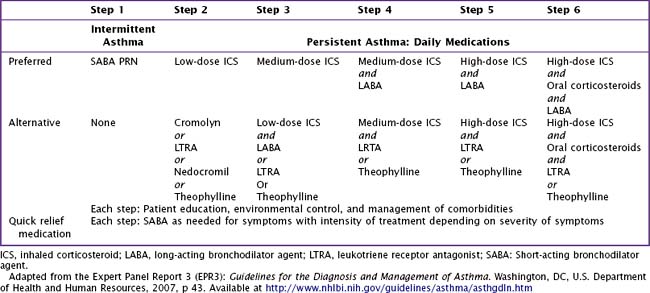

It is useful to classify a patient’s different symptoms into categories of severity (Table 38-2), which can guide stepwise treatment. Historical data provide the most useful information in establishing a diagnosis of asthma. When a tentative diagnosis of asthma is suspected based on a patient’s history and physical findings, further evaluation with spirometry is warranted.

Acute Exacerbation

A patient experiencing an acute asthma exacerbation should be promptly evaluated and triaged based on the severity of his or her symptoms (Table 38-3). Standardized criteria should be used within an institution, although many different schemes exist. Criteria are primarily based on symptom assessment, and concerning symptoms and signs include tachypnea, breathlessness, increased work of breathing, accessory muscle use, and decreased pulse oximetry values. For a child old enough to perform the maneuver, obtaining peak flow measurements can aid in determining the severity of an exacerbation, with peak expiratory flows of less than 40% predicted signaling a severe exacerbation requiring further assessment in an ED. However, peak flows are not a reliable measure because they measure large airway obstruction, and one can experience a 25% decrease in small airway flow before there is any decrease in peak flow. Spirometry is a much more sensitive measure of both small and large airway function and can also be used in the acute setting to assess both severity of the exacerbation and acute response to therapy.

Table 38-3 Classifying Asthma Exacerbation Severity in Children Younger Than 12 Years Old

| Symptoms and Signs | Clinical Course | |

|---|---|---|

| Mild |

ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; IV, intravenous; SABA, short-acting bronchodilator agent.

Adapted from the Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Washington, DC, U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources, 2007, p 54. Available at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm.

Management

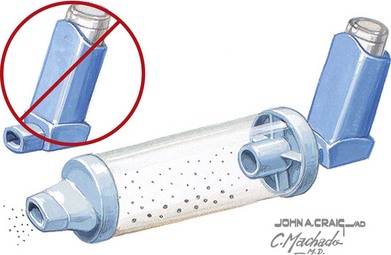

For patients requiring therapy, the mainstays of treatment include administration of bronchodilators and inhaled or systemic corticosteroids (Figures 38-4 and 38-5).

Chronic Disease

For long-term control, an inhaled corticosteroid is the preferred treatment. In general, patients with asthma should receive the minimal therapy indicated to control their symptoms (Table 38-4). If comorbid medical conditions are present, they should also be treated (i.e., a patient with allergic rhinitis should receive intranasal corticosteroids or oral antihistamine therapy). Depending on the severity of a patient’s asthma symptoms, he or she should be reassessed at regular intervals after initiation of treatment to evaluate response to therapy and the need for adjustment of therapy.

Bhogal S, Zemek R, Ducharme FM: Written action plans for asthma in children, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD005306, 2006.

Bleecker ER, Postma DS, Lawrance RM, et al. Effect of ADRB2 polymorphisms on response to longacting beta2-agonist therapy: a pharmacogenetic analysis of two randomised studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9605):2118-2125.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/index.htm, 2007. Available at

Robinson PD, Van Asperen P. Asthma in childhood. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56(1):191-226.