Assessment of the Amputee

An amputation is defined as the removal of part or all of a limb or some other outgrowth of the body. If fingers and partial non-mutilating hand injuries are excluded, lower-limb amputations are much more frequent than upper-limb amputations.1 However, upper-limb amputations cause greater functional loss because the upper limbs are used more functionally and in many more diverse ways. There is also a greater functional sensory loss when an upper limb is involved. In addition, the upper-limb amputation causes a more obvious disfigurement and alteration of body image, which affects the actions and reactions of both the amputee and those with whom he or she interacts.1,2 Amputations are considered to be a treatment of last resort when other methods, such as revascularization or reattachment, have failed or are not considered suitable treatment options.2–5 Assessment of the amputee patient may involve assessing a patient before the amputation or after the amputation has taken place. In the first instance, the assessment is primarily carried out by one or more physicians deciding whether there is a need for such a procedure and then deciding the level at which the amputation should occur. In some cases, indexes or scores6–19 may be used although some20 have questioned their usefulness in the final outcome, especially in the case of trauma.

There are several indications for amputations.21 The most common are trauma caused by compound fractures, blood vessel rupture, stab or gunshot injuries, compression injuries, severe burns, or cold injuries;22 and vascular disease as the result of systemic problems, such as diabetes, arteriosclerosis, embolism, venous insufficiency, or peripheral vascular disease often aggravated by cigarette smoking.23 About 75% of amputations in older patients fall within this second category.24 The presence of suspected vascular disease may include more than the physical examination when considering whether to amputate. These other tests include blood tests, chest x-rays, electrocardiography, Doppler studies, arteriography, venograms, thermography, and transcutaneous PO2 readings.22 When trauma is the cause, the aim of the amputation is to restore maximum length with good soft-tissue covering.22 In addition, amputations may be performed because of infections, tumors (both benign and more commonly, malignant types), neurological disorders (e.g., an anaesthetic limb from, for example, a complete plexus avulsion25), congenital deformity (e.g., partial or total absence of a limb), and amputations for cosmetic reasons (e.g., extra digit).25–28 Younger people tend to experience more congenital, malignancy, and trauma-related amputations, whereas older people experience multiple pathophysiological mechanisms, as previously mentioned.

The examiner who has the opportunity to do a preoperative physical assessment of the patient who has been scheduled for an amputation should take the time to determine the patient’s available muscle strength, range of motion (ROM), and functional mobility bilaterally to provide a baseline for future comparison if necessary. The size and position of any abnormal tissue degeneration or potential pressure areas should be recorded accurately, and functional levels should be assessed and recorded. If at all possible in this preoperative period, the patient should be given some instruction in bed mobility, as well as climbing in and out of bed with or without support. In addition, the examiner should ensure that the patient knows how to provide suitable care for pressure areas and preserve joint mobility to prevent any contractures from forming. If a lower-limb amputation is anticipated, the patient should be taught to use ambulatory aids such as crutches or wheelchair so that he or she can maintain as much mobility as possible after the amputation.

Levels of Amputation

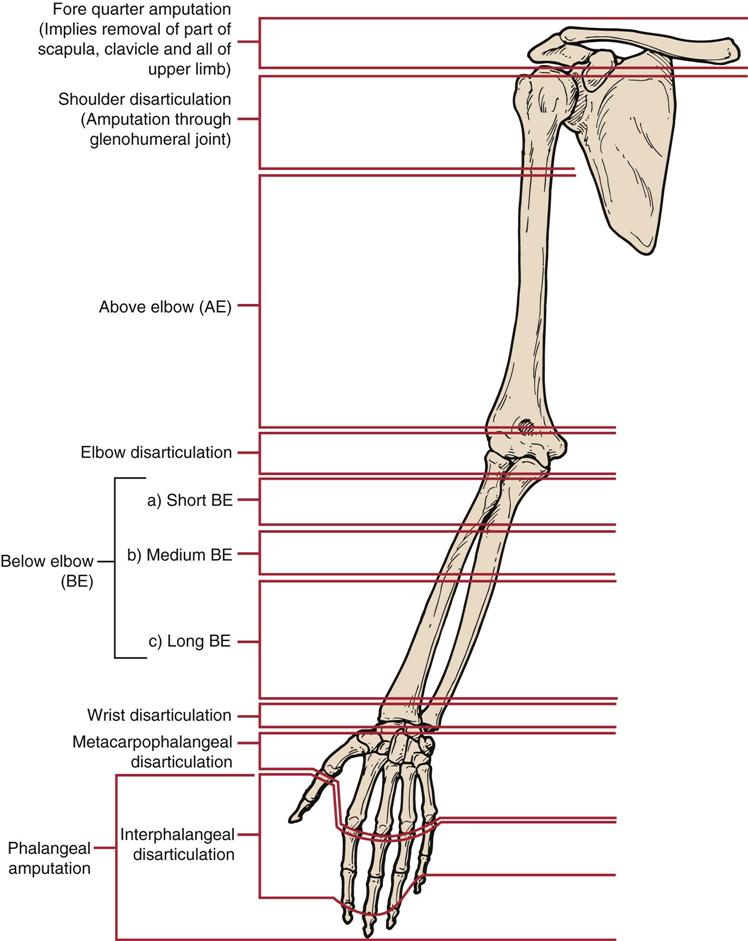

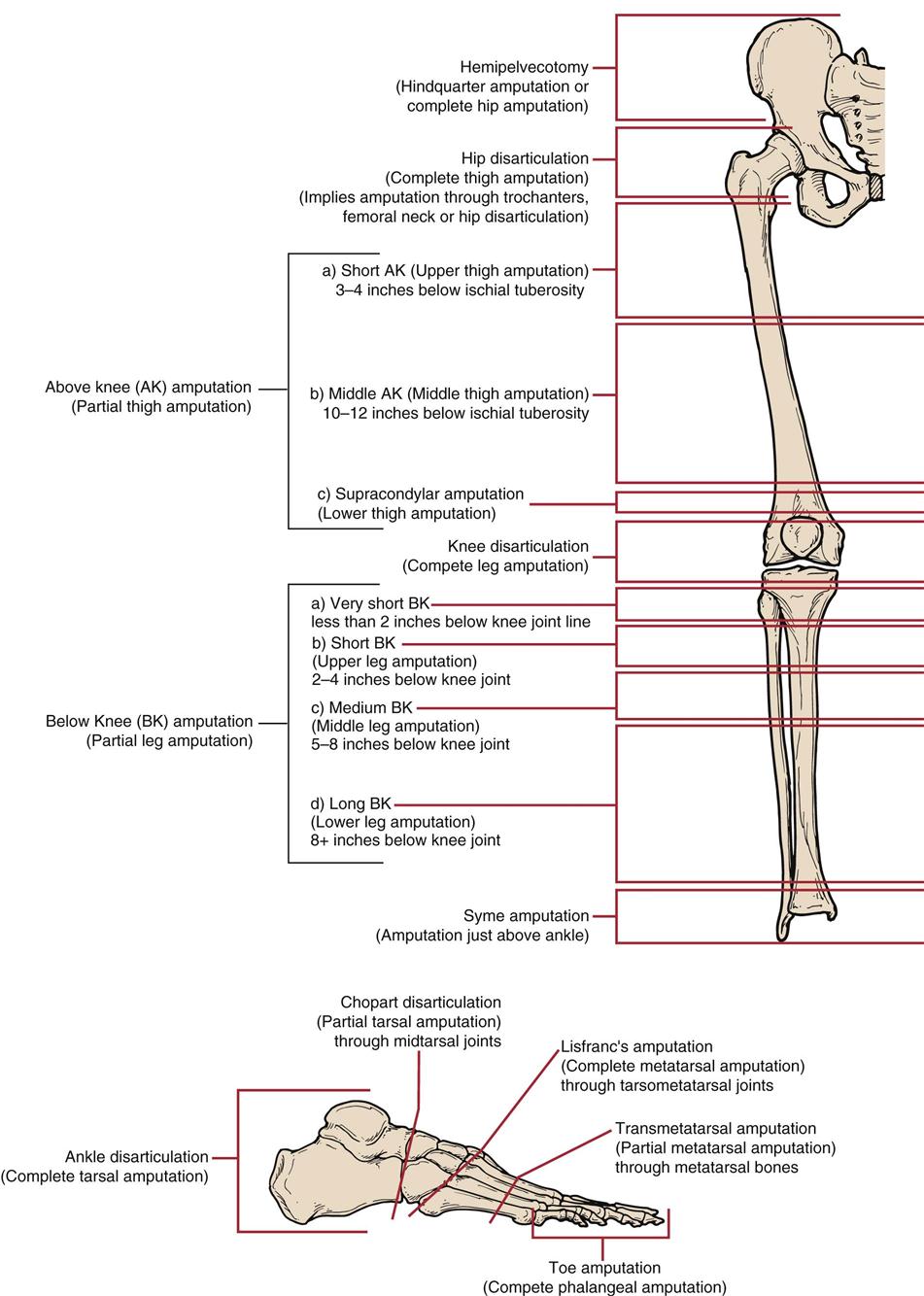

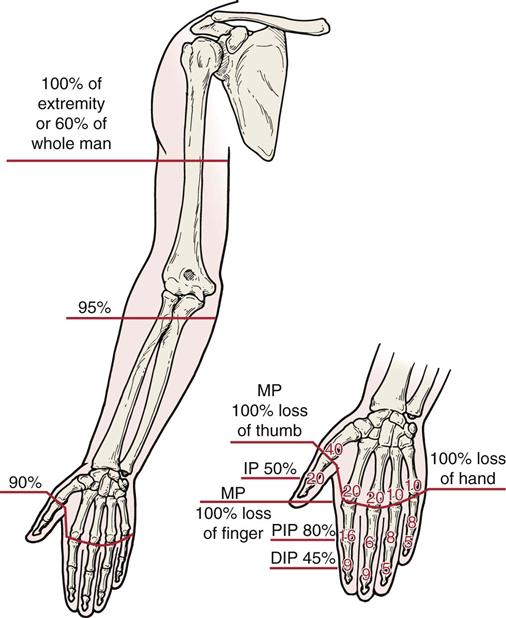

Amputation surgery, whether performed to the upper limb or the lower limb, can occur at various levels (Figures 16-1 and 16-2).29 For the most part, this chapter deals with assessment of the lower-limb amputee primarily, because these amputations are more common. However, functional loss is usually greater for upper-limb amputees. Thus upper-limb amputee assessment deals much more with different functional demands than lower-limb assessment. Figure 16-3 shows the percentage impairment caused by an upper-limb amputation.30

Percentage of impairments related to whole body, extremity, hand, or digit. DIP, Distal interphalangeal; IP, interphalangeal; MP, metacarpophalangeal; PIP, proximal interphalangeal. (Redrawn from Swanson AB, de Groot Swanson G, Goran-Hagert C: Evaluation of hand function. In Hunter JM, Schneider LH, Mackin EJ, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand, St Louis, 1990, Mosby, p. 119.)

Amputation surgery may be one of two types—open or closed. Open, or primary, amputation is used in cases of infection in which the wound is left open after the amputated part is removed to allow clearance of infection. It requires a second procedure to close the wound. More commonly, a closed amputation is performed. This procedure is used when tissue viability is as normal as possible. At the time of the amputation, the skin flaps are closed, as is the wound. Commonly, the skin flaps are closed on the posterior and distal aspect of the stump because adhesions are less likely and an incision line is further from the bone, but other methods are also sometimes used.31 The goal of amputation surgery is to create a dynamically-balanced residual limb with good motor control and sensation.32 The patient will need a well-healed, well-shaped residual stump with the greatest functional length possible in the limb.32 The higher the level of the amputation, the greater the handicap.25 In the lower limb, immediate prosthetic fitting helps facilitate early mobilization with more normal gait patterns.26 Amputation should be considered to be a reconstructive procedure leaving the patient with the best of possible alternatives.33

The second opportunity where the amputee patient may be assessed is following the surgery. This is more likely to be done by the physician or other health care professionals. In this case, the aim of the assessment is primarily to determine what functional deficits the patient has, to assess the fitting of the prosthesis, and to watch for complications. A good assessment enables the clinician to assist the patient in understanding and dealing with the specific physical and social limitations that the amputation has brought to his or her pattern of life.34 This second scenario is described in the remainder of this chapter.

Patient History34

As with any assessment, the initial part of the examination will include the patient’s history as it relates to the amputation, its cause, and any related factors. When doing the assessment of the amputee, it is important to determine the patient’s past medical, surgical, preoperative ambulatory, and functional status for both upper and lower limbs, and preoperative symptoms. As part of this “past history,” the examiner must develop some understanding of the patient’s recreational activities, past psychiatric history (which may include information on alcohol or drug abuse), current stressors (including recent losses), pain tolerance, previous association with patients who have disabilities, and compliance with medical treatments.24 In addition, information on family structure and possible support groups, including family and friends, must be discussed. Issues such as marital status, sexual history, family roles including familial support, strengths, and problems should be ascertained, because they can impact greatly the outcome and how the patient ultimately functions as an amputee.35,36

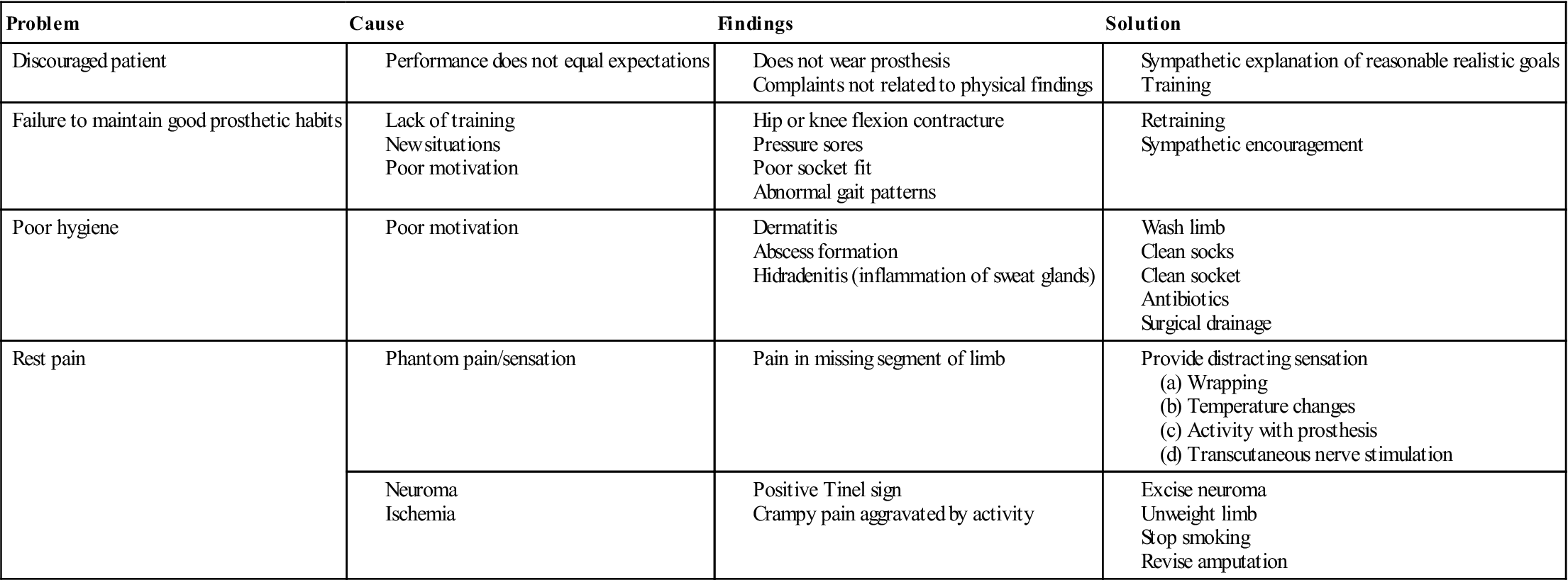

The examiner must determine and develop an understanding for any patient anxieties, why they are present, whether these anxieties can be dealt with by the examiner or if other health care specialists need to be involved, what the patient imagines his or her future to be, and how the disability will change his or her lifestyle, social relations, vocational future, and self-concept (Table 16-1). All these factors must be considered if the examiner hopes to have a successful outcome to treatment.

TABLE 16-1

Patient Motivational and General Problems

| Problem | Cause | Findings | Solution |

| Discouraged patient | |||

| Failure to maintain good prosthetic habits | |||

| Poor hygiene | |||

| Rest pain | |||

Modified from Smith AG: Common problems of lower extremity amputees. Orthop Clin North Am 13:576, 1982.

For the present medical history, the following questions should be asked:

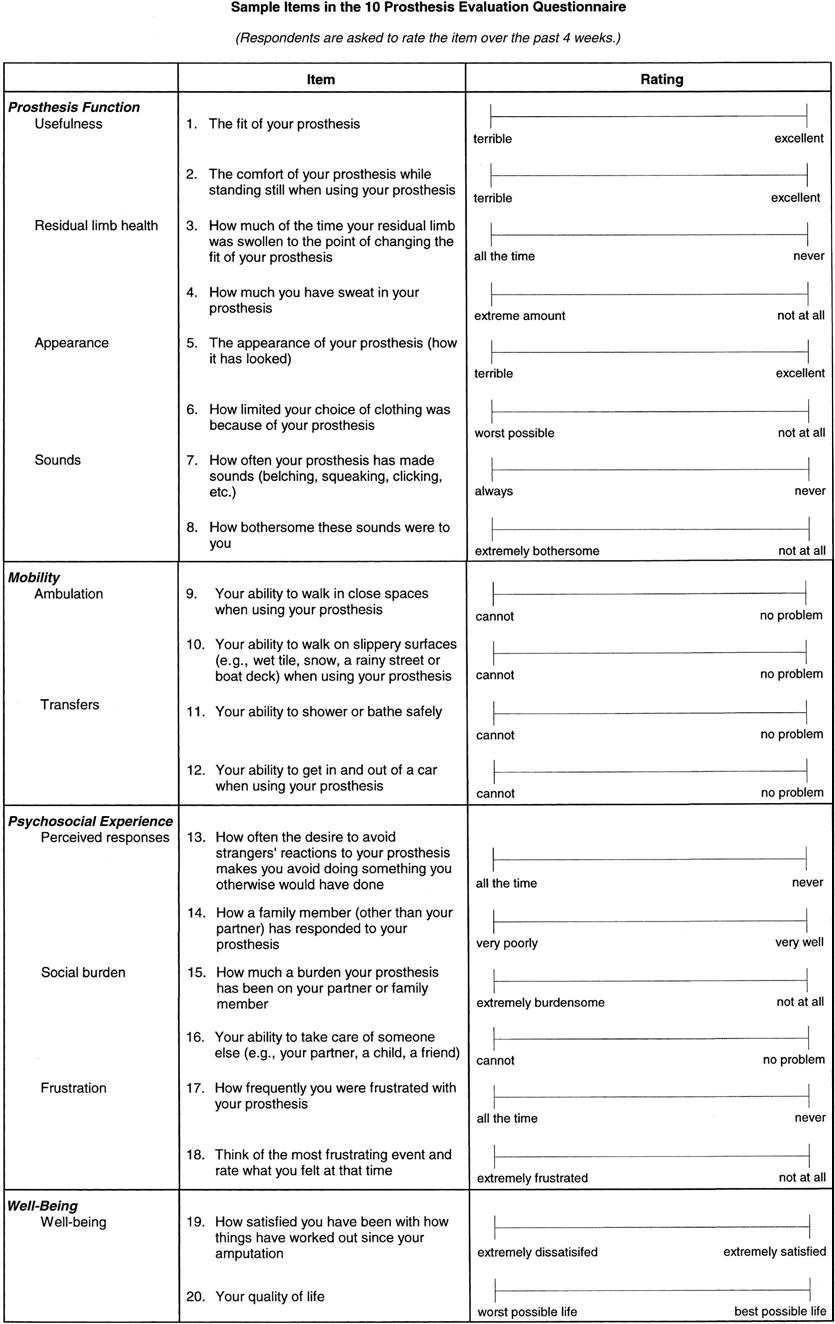

5. If the patient has a prosthesis, what does the patient think about the prosthesis, its fit, and its function? How long has the prosthesis been worn? (Years? Months?) How long is the prosthesis worn each day? Is it worn every day? Is the suspension adequate? Are there any skin abrasions? Inadequacies in these areas will lead to patient frustration, to disappointment, and, ultimately, to the patient becoming discouraged about using the prosthesis and, in fact, may come to the state where the patient does not want to wear the prosthesis. If the prosthesis is uncomfortable or excessively noisy, it is unlikely the patient will use it, or if it is used, it is unlikely the patient will use it properly. In the case of a lower-limb prosthesis, the patient may refuse to bear weight on the prosthesis. Cosmesis is another problem that is often of concern for amputees, especially for women, and when the amputation is in the upper limb the extremity is sometimes not covered with clothing. The examiner must differentiate between the discomfort of using something new and the discomfort caused by a specific prosthetic fault. In some cases, a prosthesis evaluation questionnaire (PEQ)37 may be useful (Figure 16-4).

6. Has the patient been looking after the stump properly, ensuring proper limb and sock hygiene? Failure to do so easily leads to complications, such as skin breakdown, infection, and ulcers (see Table 16-1).32 The remaining stump should be washed with care using mild soap. The stump sock should be changed and cleaned regularly, and the prosthesis socket should also be cleaned regularly with mild soap and water.32

7. Does the patient have any pain or abnormal sensation? Where is the pain or abnormal sensation? Is the pain intermittent or constant? What is the intensity of the pain (a visual analogue scale may be used—see Figure 1-4)? Where is the pain? What type of pain or abnormal sensation is it? Phantom sensation is an abnormal feeling the patient has for the limb, but the patient feels the sensation as being in the amputated part of the limb even though that part of the limb is not there.22,38–40 This sensation is an almost universal consequence of limb amputation.41,42 It may take numerous forms, including the feeling that someone is touching the amputated limb, pressure being applied to the missing body part, cold, wetness, itching, tickle, pain, or fatigue. The intensity of these sensations may vary and may change over time. The sensations commonly have different meaning to different people. Phantom sensations are more commonly felt in the distal part of the excised extremity, because the distal part of an extremity tends to be more richly innervated.38

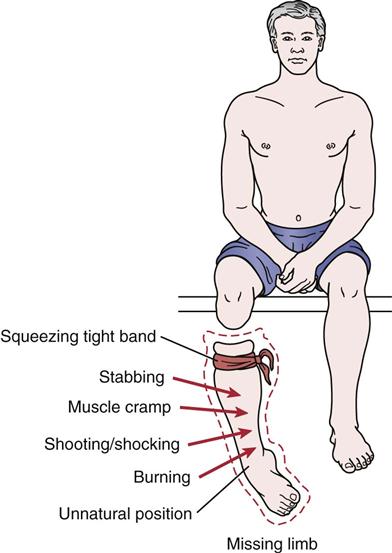

Phantom pain is described as a painful sensation perceived in the missing body part in the case of an amputation, in the paralyzed part of a spinal cord injury patient, or following a nerve root avulsion in the case of a neurological injury.22,38–41 Eighty percent of amputees experience some phantom pain sometime during the injury healing process. Phantom pain is relatively common, but it is unpredictable in terms of predisposing factors, severity, frequency, duration or character, aggravation by internal or external stimuli, or type of pain experienced.38 Phantom pain is more likely to be seen in the upper-limb amputee than in the lower-limb amputee, and it tends to be more prolonged in the upper limb. Some patients report that the pain is of very high intensity, which may be evoked by some external or internal stimuli, whereas others report a dull, continuous aching or burning that does not seem to be episodic. Many amputees describe the pain as being knifelike, burning, sticking, shooting, prickling, throbbing, cramplike, squeezing, “like something trying to pull my leg off,” or some type of electrical phenomenon (Figure 16-5).39,41 Phantom pain generally begins within the first postsurgical week, commonly stabilizes after a few months, but may occur several months or years after the amputation. It seems to decrease in frequency, duration, and severity during the first 6 months. Most commonly, phantom pain persisting beyond 6 months is very difficult to treat and usually does not change in character after that time. Some people, however, report that the intensity of pain changes with time. Prolonged healing or other complications, such as fractures, may cause phantom pain to persist for longer periods.

Some of the typical painful feelings that seem to stem from the missing limb. (Redrawn from Sherman RA: Stump and phantom limb pain. Neurol Clin 7:250, 1989.)

Stump pain is pain arising from the residual part of the body as opposed to phantom pain, which is felt in the missing part of the body.22,38,39,41,42 It is commonly a sharp, sticking, or pressure feeling that, although diffuse, is localized to the end of the stump.39 Stump pain is usually the result of six primary etiologies—prosthogenic, neurogenic, arthrogenic, sympathogenic, referred, and abnormal stump tissues.38 The most common cause of stump pain is prosthogenic, which implies improper fitting of the prosthesis. The second type of stump pain is neurogenic, most commonly from the formation of a neuroma where the nerve was cut during surgery. Neuroma pain is usually characterized by sharp, shooting pain that can be evoked by light tapping over the neuroma (Tinel sign). Third, stump pain may be arthrogenic or coming from an adjacent joint or surrounding tissues, usually as a result of changing stresses to the tissues or because sufficient time has not been allowed for the tissues to adapt to the new stresses being applied to them. For example, back pain is initially a common finding in above-knee (AK) amputees.42 Fourth, stump pain may be sympathogenic or associated with the sympathetic nerve system. This pain is sometimes called causalgia, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, or, as some people now call it, sympathetically maintained pain. Fifth, the pain may be referred. Non-radicular referred pain can come from the joints, muscles, or myofascial conditions. Last, abnormal tissue, such as bony exostosis, heterotrophic ossification, adherent scar, or sepsis (infection), can lead to pain in the remaining stump. Virtually every amputee experiences stump pain after amputation. Stump pain is a normal result of major surgery. However, it is frequently a shock to those patients who are not warned to expect it.41 Stump pain is usually severe immediately after amputation and subsides quickly with healing. It tends to be more evident in patients who have nondecreasing phantom pain.39 About 80% of amputees have functionally significant episodes of phantom or stump pain every year and may have almost constant, very low level, stump and phantom pain that they define as being over the threshold of nonpainful sensation.41

There is no evidence that phantom pain or stump pain is caused by psychological disorders although stress and psychological disturbances can exacerbate the pain.41 They are both considered to be physiological phenomena.

Observation34

Following surgery, the examiner will observe the stump for any swelling and whether healing is occurring properly. The condition of the skin as well as the presence of joint contractures, especially if the amputation is close to a joint (e.g., below-knee [BK] amputation), should be noted. The amputee should be observed both without the prosthesis and while wearing the prosthesis. Generally, the lower-limb amputee is observed in three positions while wearing the prosthesis: standing, sitting, and walking.

To begin the observation of the amputee, the examiner first looks at the remaining good limb, noting sensation, pulses, temperature, and skin condition. The examiner takes time to observe the remaining limb that will have to take a greater functional role and often greater stresses because of the amputation to the other limb. If it is a lower-limb amputation, the remaining limb will have to take a greater load during gait. Are the skin and nails normal, or are trophic changes evident? Are there any sores or open areas? These changes may indicate circulatory impairment. What are the color and temperature of the remaining limb? Do they fall within normal limits? Are the pulses (e.g., femoral, tibial, dorsalis pedis) normal? Does the limb exhibit any deformity or swelling? Will the remaining limb be able to take the additional stress?

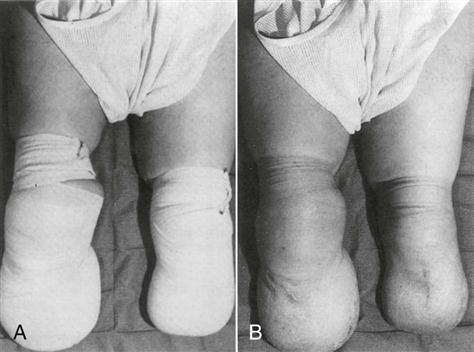

The examiner notes whether the patient is wearing the prosthesis or not. If the patient has the prosthesis on, then observation of the patient functioning with the prosthesis is first done with the patient standing, walking, and sitting. If the patient is not wearing the prosthesis, the examiner spends the initial period checking the stump and its condition, noting whether the wound is healing properly or whether there are any signs of drainage or weeping from the wound or evidence of tissue breakdown.32 If the stump is covered with an elastic wrap or shrinker to assist in decreasing swelling, the examiner should note how it is applied, whether it fits smoothly or contains wrinkles, and whether the application is effective in reducing swelling. The examiner can then ask the patient to remove the wrap. At this stage, the examiner can ask the patient to demonstrate how he or she applies the wrap (if the patient does it himself or herself), or this may be left until later.

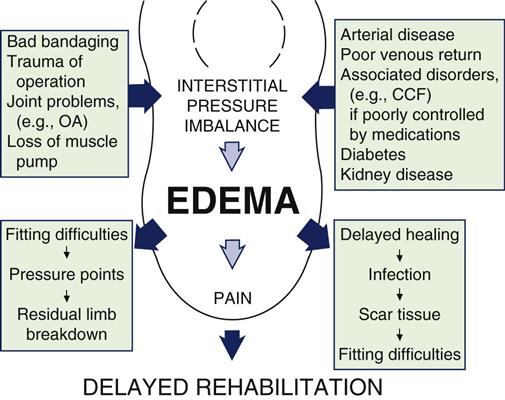

With the wrap off, the examiner then inspects the stump, noting its shape. The stump may be classed as cylindrical, conical, bony, bulbous, or edematous. The examiner looks for signs of unusual patterns of swelling (an indication the wrap has been applied incorrectly) (Figure 16-6); causes of residual limb edema (Figure 16-7); presence of skin abrasions, skin breakdown, or blisters (all of which may indicate poor prosthesis fit); or presence of infection (Table 16-2).32 The examiner should note whether the scar is healing normally and whether the sutures have been removed or some remain. The scar may be classed as non-tender, sensitive, invaginated, well-healed, open, or adherent. The location of the scar and whether it will affect the fitting of the prosthesis should be noted. Any “dog ears” to the suture, which may interfere with the prosthesis, should also be noted. The mobility of the scar and tension of the skin and its mobility, especially over the distal end of the stump, should be observed. In addition, the color and temperature of the stump should be noted. Any potential weight-bearing areas (e.g., ischial tuberosity–AK amputation; patellar tendon–BK amputation) should also be inspected because these tissues will receive greater stress with the use of a prosthesis. The condition of the remaining joints and their supporting musculature (e.g., atrophied, fleshy, strong) should be noted.

A, An incorrectly applied bandage. B, The uneven residual limb contour produced by the incorrectly applied bandage. (From Engstrom B, Van de Ven C: Therapy for amputees, Edinburgh, 1999, Churchill Livingstone, p. 53.)

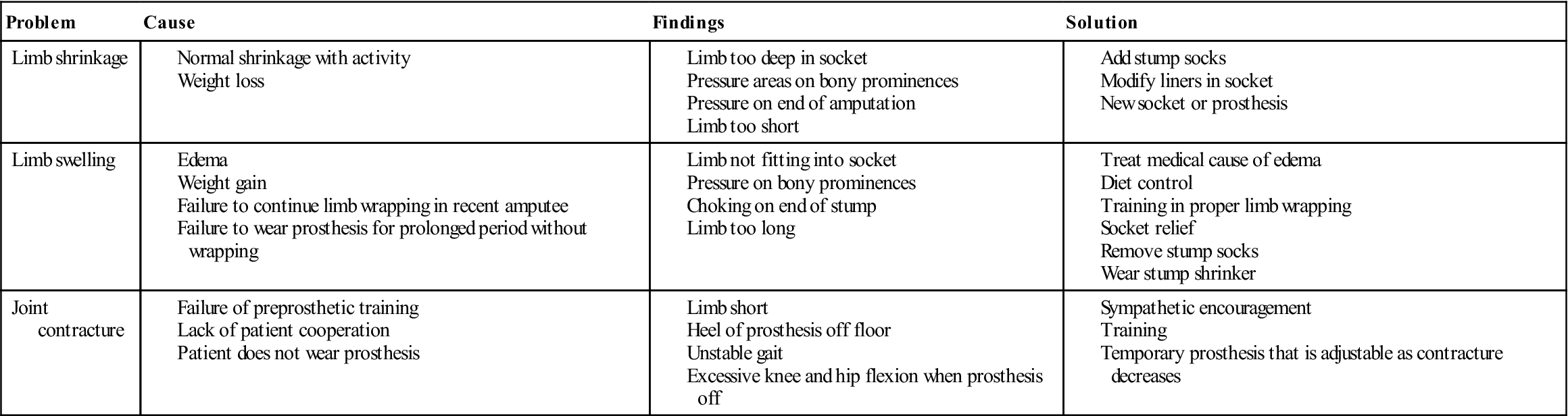

TABLE 16-2

Modified from Smith AG: Common problems of lower extremity amputees. Orthop Clin North Am 13:570, 1982.

If the patient has a prosthesis, the prosthesis is then inspected (Table 16-3). The examiner should note the socket type, the material used to construct it, and the type of suspension. The general workmanship of the prosthesis and whether it is satisfactory should be noted. The examiner should inspect the trim lines, the rivets, and other fastenings to see if they are neat and secure. Joint covers should shield mechanical joint heads to prevent damage to clothing. There should be no scratches or rough areas on the prosthesis. Plastic lamination should be uniform without appreciable missed areas.

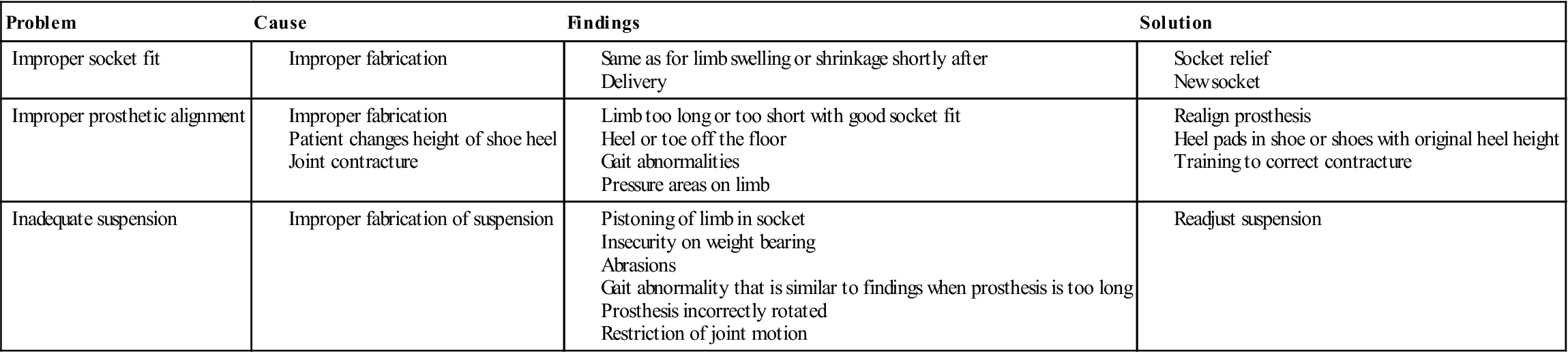

TABLE 16-3

Problems Related to the Prosthesis

| Problem | Cause | Findings | Solution |

| Improper socket fit | |||

| Improper prosthetic alignment | |||

| Inadequate suspension |

Modified from Smith AG: Common problems of lower extremity amputees. Orthop Clin North Am 13:574, 1982.

Next, provided the patient is at the stage where the prosthesis has been fitted (in some cases, especially in the lower limb, the prosthesis may be fitted right after surgery; in other cases, the prosthesis is fitted after tissue healing is ensured), the patient is asked to put the prosthesis on while the examiner determines whether the patient can correctly and easily do this independently or only with help.

For the lower-limb amputee, once the prosthesis is fitted, the patient is first observed in standing position. As with the patient who is not an amputee, posture of the patient is assessed (see Chapter 15) and the examiner must determine if any deviations are structural or due to the prosthesis. In addition, the examiner notes the following:

5. Is the suspension, if present, adequate and fully supporting the prosthesis during weight-bearing? Is the suspension adjustable if necessary?43

Next, the patient is observed seated while wearing the prosthesis. The examiner notes the following:

The third phase of lower-limb amputee observation is to view the patient walking while wearing the prosthesis. During walking, the examiner should watch for hip or knee instability or abnormal gait. During this phase, the examiner observes the following:

1. Is the patient’s performance and walking on a level surface satisfactory? Any gait deviation that requires attention should be noted. Gait deviations include an abducted or adducted gait, lateral trunk bending, circumduction, medial or lateral whip of the prosthesis, foot rotation on heel strike, uneven heel rise, foot slap, uneven step length, and vaulting. Also, the stump may be oversensitive and/or painful. A very short stump may fail to provide a sufficient lever arm for the pelvis. Finally, an abnormal gait pattern may develop because of a habitual pattern of movement.22,44 A prosthesis aligned in abduction may cause a wide base gait resulting in this abnormal gait pattern. Amputee balance may be difficult if an adduction contracture is present. An abducted gait is characterized by a very wide base with the prosthesis held away from the midline at all times. If the prosthesis is the cause of the abducted gait, it may be that the prosthesis is too large or that too much abduction may have been built into the prosthesis. A high medial wall may cause the amputee to hold the prosthesis away to avoid pressure on the pubic ramus. The pelvic band may be positioned too far away from the patient’s body. This defective gait may also be caused by an abduction contracture or a poor habitual pattern of gait.22,44

Lateral bending of the trunk is characterized by excessive bending laterally, generally toward the prosthetic side, from the midline. If the prosthesis is the cause, it may be that it is too short or has an improperly shaped lateral wall that fails to provide adequate support for the femur. A high medial wall may cause the amputee to lean away to minimize the discomfort.

A circumduction gait is a swinging of the prosthesis laterally in a wide arc during the swing phase of gait. This defect may be due to the prosthesis being too long or the prosthesis having too much alignment stability or friction in the knee, making it difficult to bend the knee during the swing-through phase of gait. The amputee may have an abduction contracture of the stump or may lack confidence in flexing the prosthetic knee because of muscle weakness, or the amputee may fear stubbing the toe. Finally, this abnormal gait pattern may be the result of a habitually incorrect gait pattern.22,44

Medial or lateral whips are observed best when the patient walks away from the observer. A medial whip is present when the heel travels medially on initial flexion at the beginning of the swing phase, whereas a lateral whip exists with the heel moving laterally. If whipping occurs, then it is the fault of the prosthesis. Lateral whips are commonly seen from excessive medial rotation of the prosthetic knee. A medial whip may result from excessive lateral rotation of the knee. The socket may fit too tightly, thus reflecting stump rotation. Excessive valgus in the prosthetic knee may contribute to this defect. Also, a badly aligned toe break in the conventional foot may cause twisting at toe-off. Faulty walking habits by the amputee may also result in whips.22,44

Rotation of the prosthetic foot on heel strike is due to too much resistance to plantar flexion caused by the plantar flexor bumper or heel wedge.22,44 If too much toe-out has been built into the prosthesis or if the socket fits too loosely, it may also cause a similar gait fault. If the amputee has poor stump muscle control or extends the stump too vigorously at heel strike, the same gait fault can occur.

If the amputee exhibits uneven arm swing, the altered gait may be due to poor balance, fear or insecurity, or a poor habitual pattern.

A long prosthetic step is seen when the amputee takes a longer step with the prosthesis than with the normal leg. If the prosthesis is at fault, it is usually due to insufficient initial flexion in the socket where a stump flexion contracture is present.22,44

Foot slap is a too rapid descent of the anterior portion of the prosthetic foot. It is commonly the result of plantar flexion resistance in the prosthesis being too soft, or the amputee may be driving the prosthesis into the walking surface too forcefully to ensure extension of the knee.22,44

Uneven heel rise is characterized by the prosthetic heel rising too much or too rapidly when the knee is flexed at the beginning of the swing phase. If the prosthesis is at fault, the knee joint may have insufficient friction, and there may be an inadequate extension aid. The amputee may also be using more power than necessary to force the knee into flexion.22,44

Uneven timing is characterized by steps of unequal duration or length, usually by a very short stance phase on the prosthetic side. An improperly fitting socket may cause pain and a desire to shorten the stance phase on the prosthetic side. A weak extension aid or insufficient friction in the prosthetic knee can cause excessive heel rise and thus result in uneven timing because of a prolonged swing-through. Alignment stability may also be a factor if the knee buckles too easily. In addition, the amputee may have weak muscles in the stump and may not have developed good balance. Fear and insecurity may also contribute to this defect.22,44

Terminal swing impact is characterized by rapid forward movement of the shin piece allowing the knee to reach maximum extension with too much force before heel strike. If the prosthesis has insufficient knee friction or the knee extension aid is too strong, this gait fault may be seen. In addition, the amputee may be trying to assure himself or herself that the knee is in full extension by deliberately and forcefully extending the stump.22,44

The amputee who feels unstable at the prosthetic knee may develop a feeling of instability that could lead to the danger of falling. In this case, the prosthetic knee joint may be too far ahead of the thigh, knee, ankle (TKA) line and insufficient initial flexion may have been built into the socket. Plantar flexion resistance may also be too great, causing the knee to buckle at heel strike. Failure to limit dorsiflexion can lead to incomplete knee control. Also, the amputee may have weak hip extensor muscles or a severe hip flexion contracture leading to instability.22,44

Drop-off at the end of stance phase is characterized by a downward movement of the trunk as the body moves forward over the prosthesis. The prosthesis is at fault if there is inadequate limitation of dorsiflexion of the prosthetic foot. The keel of a solid ankle cushion heel (SACH)-type foot may be too short, or the toe break of the conventional foot may be too far posterior. The socket may have been placed too far anterior in relation to the foot.22,44

Excessive trunk extension during the stance phase in which the amputee creates an active lumbar lordosis may also be seen in some amputees. If the prosthesis is at fault, it may be due to an improperly shaped posterior wall causing forward rotation of the pelvis to avoid full weight bearing on the ischium. It may also be due to insufficient initial flexion being built into the socket. In addition, the amputee may demonstrate hip flexor tightness or weakness of the hip extensors and may be attempting to substitute with the lumbar erector spinae muscles. Weak abdominal muscles contribute to this defect. The deviation may be due to a habitual pattern with the patient moving his or her shoulders backward in an effort to obtain better balance.22,44

Vaulting is characterized by rising on the toe of the normal foot to permit the amputee to swing the prosthesis through with little or no knee flexion. If the prosthesis is the cause, it may be too long or there may be inadequate socket suspension. Excessive alignment stability or some limitation of knee flexion, such as a knee lock or strong extension aid, may lead to altered gait. Vaulting is a fairly frequent habitual pattern that amputees develop. The amputee may also have fear of stubbing the toe, which could lead to this abnormal gait, or there may be some stump discomfort.22,44

The reader is referred to Lusardi, et al.44 and Engerstrom and Van de Ven22 for further information on prosthetic gait. Normally, gait deviations observed in BK amputees are fewer and less noticeable than in AK amputees.

3. Are the socket and suspension systems comfortable?

4. Does the prosthesis function quietly? Any noises coming from the prosthesis should be noted and the source of the noise determined. Occasionally, hissing may be heard as air enters and escapes from the socket as the amputee walks. This is associated with the piston action caused by inadequate suspension and poor socket fit or poor congruence between the socket and liner.32,43

After checking the gait while wearing the prosthesis, the prosthesis should be removed to check the patient’s stump for tissue stress from the gait activity. At this stage, the examiner observes the following:

Examination

Before the examination, the examiner should read the operative report to determine which muscles have been cut or how they have been stabilized along with the amputation since this gives the examiner some idea of the muscles available to move the limb and prosthesis and to provide stability during functional movement.

Measurements Related to Amputation

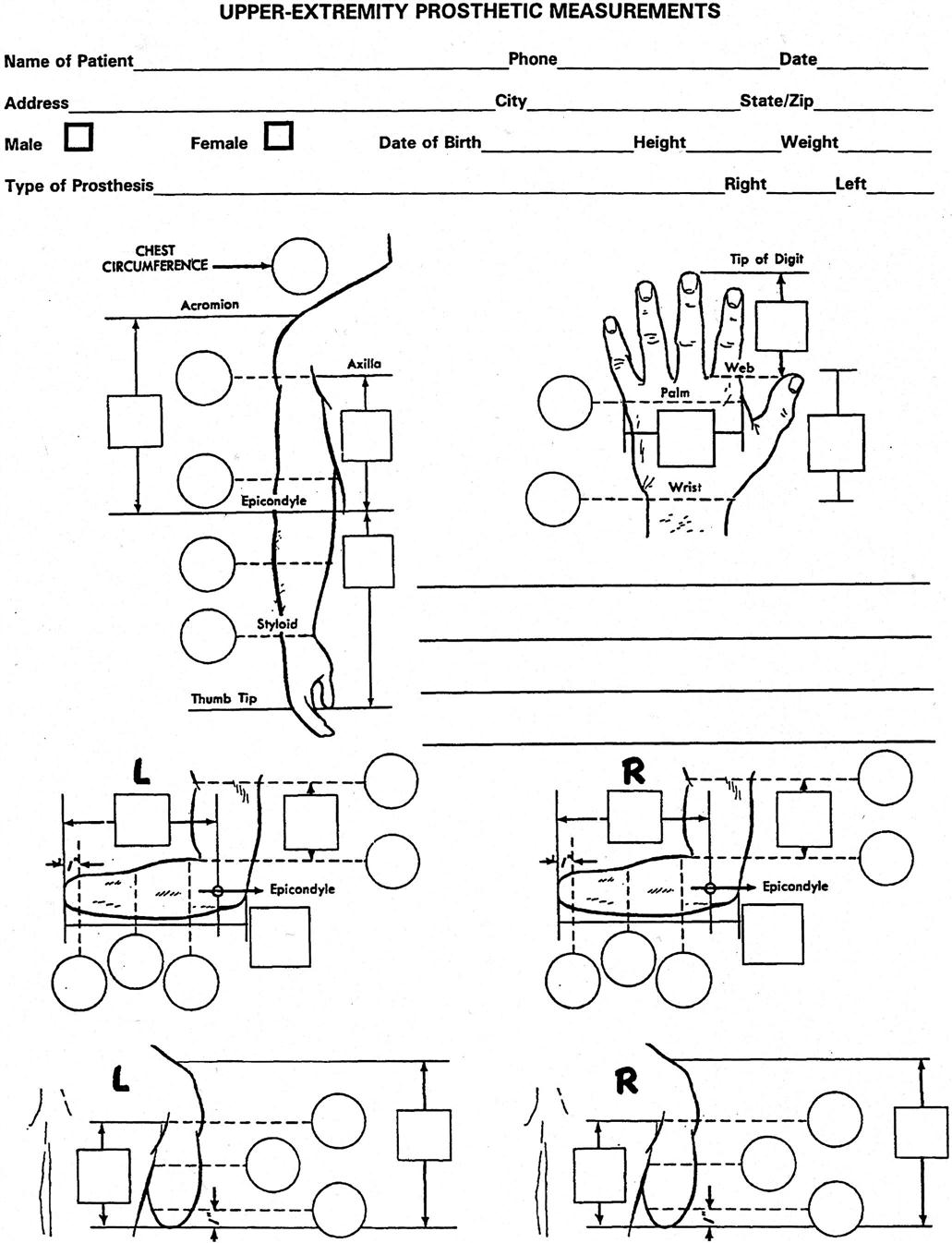

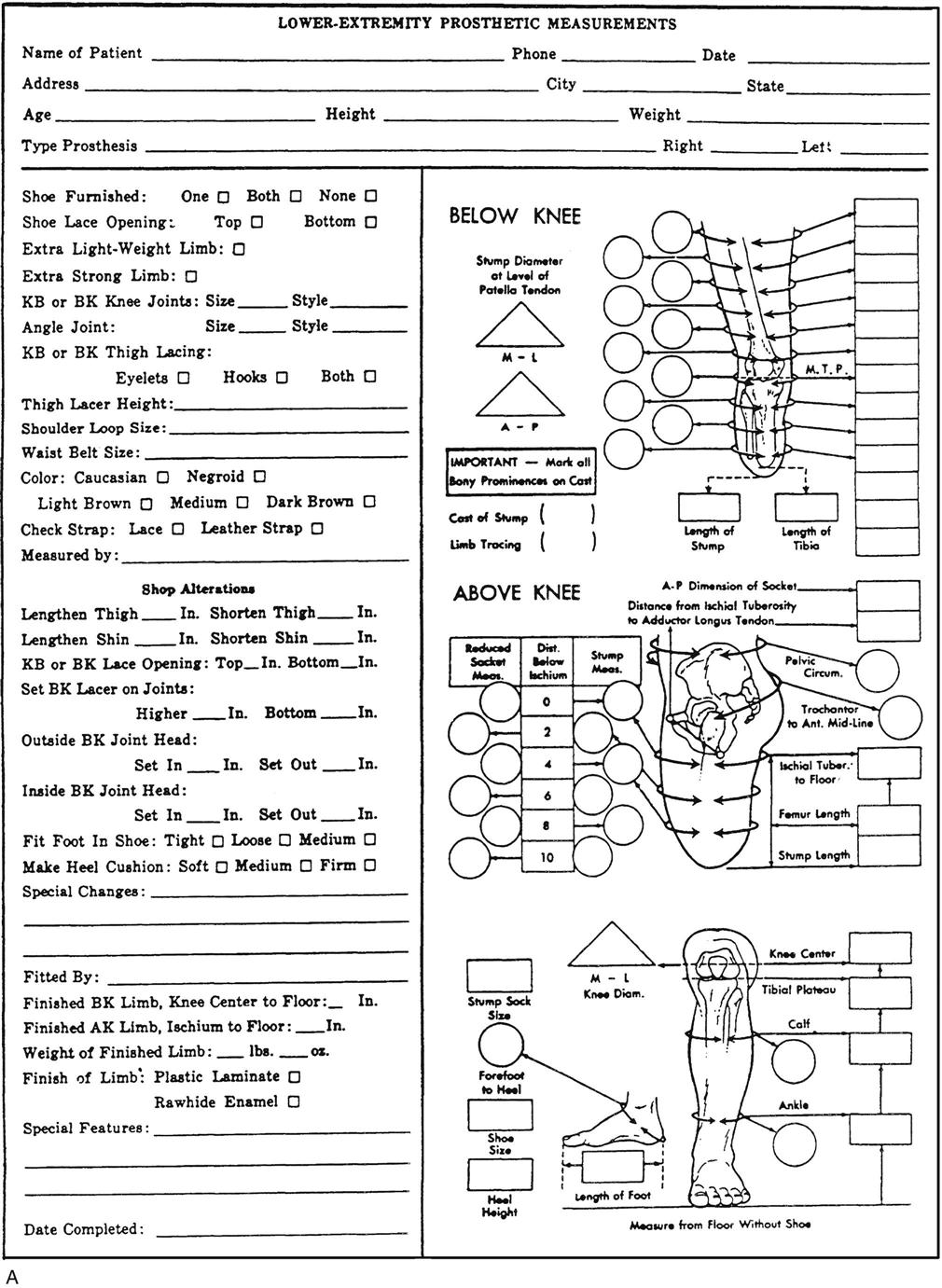

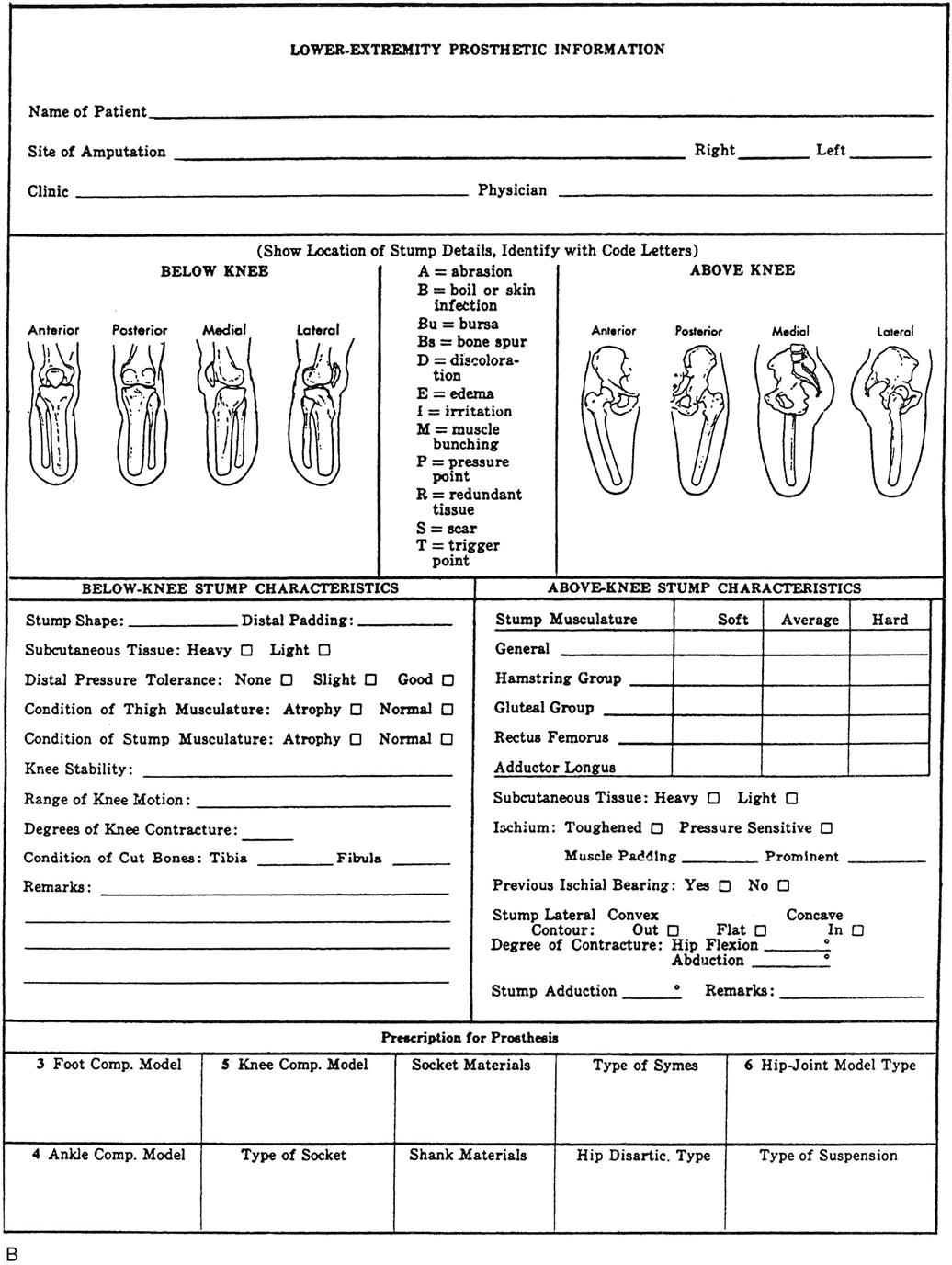

The examiner should note the length and circumference of the stump as well as scar length. Methods of measuring for prosthesis fitting are shown in the accompanying forms (Figures 16-8 and 16-9). Other measurements include the following:

Active Movements

When assessing the amputee, the examiner must determine the ability (strength and endurance) of the muscles to move the remaining joints in the remaining stump and the range of active motion available in those joints. Ideally, ROM at the remaining joints should be close to normal but may be affected by contractures or scarring. This is especially true for the hip and knee in lower-limb amputees. The ROM available helps determine the patient’s ability to move and control the prosthesis as well as whether the muscles are able to control the available ROM and provide stability when the patient is in the prosthesis. In addition, the strength, endurance, and ROM of the opposite good limb must be assessed, because greater stress will be placed on this limb, especially in the lower-limb amputee. In the case of an upper-limb amputee, if it has been the dominant limb that has experienced the amputation, the other limb will become the dominant limb of necessity, and new skills will have to be learned by that limb. In either case, a thorough assessment of the functional status of the remaining whole limb will be necessary, in addition to the examination of the amputated limb. The active movements performed would be the same as those listed for the individual joints in other chapters in this book.

Passive Movements

Passive movements of the amputated limb and remaining normal limb are necessary to ensure the necessary ROM is available and to prevent contractures or to restore ROM after contractures occur. For example, BK amputees are prone to hip flexion and knee flexion contractures, especially if the amputee spends long periods sitting in bed or in a wheelchair. The passive movements performed would be the same as those listed for the individual joints in other chapters in this book. Passive movements give the examiner an understanding of the end feel present so that if contractures occur, proper stretching treatment can be instituted. If laxity or instability is present, the patient can be instructed in proper stabilization exercises.

Resisted Isometric Movements

Resisted isometric movements should be performed on the muscles of the amputated limb as well as the remaining normal limb to ensure the patient has the strength and endurance (or exercise tolerance) that will enable the patient to use a prosthesis.45 Resisted movements of all muscles of the remaining joints on both the amputated limb and the remaining limb must be tested. These resisted movements would be the same as those listed for the individual joints in other chapters in this book. In lower-limb amputations, the muscles of the hip and knee are especially important to check. In the upper limb, the muscles of the shoulder, which play a significant role in positioning the prosthesis, must be assessed. Such testing enables the examiner to develop an exercise program to ensure maximum functionality of the patient.

Functional Assessment

For the amputee, functional assessment, for example, the Rivermead Mobility Index (RMI),46 takes primary importance, so the examiner must determine the amputee’s level of function and independence both with and without a prosthesis. This assessment may involve the care of the remaining stump, ability to put on and take off the prosthetic device, and determining the patient’s anticipated level of activity and whether this activity level can be realistically met given the patient’s handicap.

For the lower-limb amputee, the examiner should determine the following:

1. The patient’s gait and endurance when walking and whether external support (crutches, cane) is necessary. Tests such as the 6- and 10-minute walk test, timed “up and go” test (TUG test), L-test for functional mobility, the modified Emory Functional Ambulation Profile, and the Amputee Mobility Predictor are outcomes that have been found to be both reliable and valid for amputees.47

3. The patient’s ability to transfer from sitting to standing and from bed to wheelchair.

4. The patient’s ability to balance in sitting and standing (e.g., the Activities Specific Balance Confidence Scale47).

5. The patient’s ability to get up from and down to different types of chairs.

6. The patient’s ability to use aids (e.g., crutches, walker) for gait training. Can the patient manage a wheelchair?

7. The patient’s ability to go up and down stairs and ramps and ability to move in confined spaces.

8. The patient’s ability to get up from and down to the floor, as well as his or her ability to kneel, pick objects up from the floor, and do similar activities.

For the upper-limb amputee, the examiner should determine the following:

Sensation Testing

The sensitivity of the stump must be tested to ensure normal sensation. Commonly, hypersensitive areas may be present that have to be desensitized. At the opposite extreme, some areas may have no sensation and require protection. In any case, sensation testing of the stump should involve, at a minimum, hot and cold sensation and light touch.

Psychological Testing

If necessary, psychological testing may be performed.1,48 Some people have little difficulty adapting to the idea of losing a limb, whereas others have great difficulty accepting the fact that they have lost a limb. This acceptance may be related to how the patient lost the limb (trauma [suddenly] or from long-term problems, such as peripheral vascular disease), how active and independent the patient was before the amputation, or the patient’s age (generally, children adapt much better to amputation and a prosthesis than adults). Sometimes, a psychological screening test, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), may be used to determine the presence of depression, situational anxiety, and possible hysterical reaction to limb loss.41

Palpation

The examiner must take time during the examination to palpate the remaining stump of the limb. When palpating, the examiner is looking for normal mobility of the remaining tissues or any tissues that are adherent that may be amenable to treatment, any tissue tenderness, state of the overlying skin, tissue tension and texture, and any differences in tissue thickness, especially in “wear areas” where pressure is applied by the prosthesis. The uninvolved side should also be palpated for comparison.

Diagnostic Imaging

Although diagnostic imaging is not commonly a prerequisite for amputation surgery, especially in trauma cases, it may be used to evaluate the amputated stump. In this case, the examiner would be looking for the following: