Chapter 18 Assessment and Interviewing

General Principles of the Psychosocial Interview

A useful guide for this area of inquiry is provided by the “11 Action Signs” (Table 18-1), which was designed to give frontline clinicians the tools needed to recognize early symptoms of mental disorders. Functional impairment can be assessed by inquiring about symptoms and function in the major life domains, including home and family, school, peers, and community. These domains are included in the HEADSS (home, education, activities, drugs, sexuality, suicide/depression) interview guide, often used in the screening of adolescents (Table 18-2).

Table 18-1 MENTAL HEALTH ACTION SIGNS

From The Action Signs Project, Center for the Advancement of Children’s Mental Health at Columbia University.

Table 18-2 HEADSS SCREENING INTERVIEW FOR TAKING A RAPID PSYCHOSOCIAL HISTORY

PARENT INTERVIEW

ADOLESCENT INTERVIEW

From Cohen E, MacKenzie RG, Yates GL: HEADSS, a psychosocial risk assessment instrument: implications for designing effective intervention programs for runaway youth, J Adolesc Health 12:539–544, 1991.

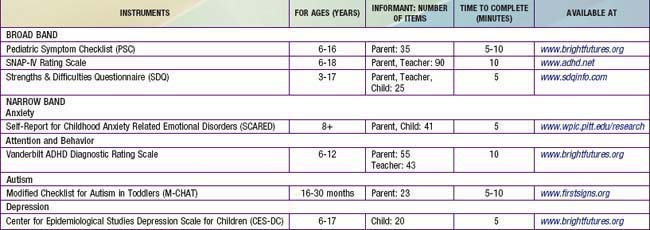

The nature and severity of the presenting problem(s) can be further characterized through the use of a standardized self-, parent-, or teacher-informant rating scale (Table 18-3 gives a sample of scales in the public domain). A rating scale is a type of measure that provides a relatively rapid assessment of a specific construct with an easily derived numerical score that is readily interpreted. The use of rating scales can ensure systematic coverage of relevant symptoms, quantify symptom severity, and document a baseline against which treatment effects can be measured.

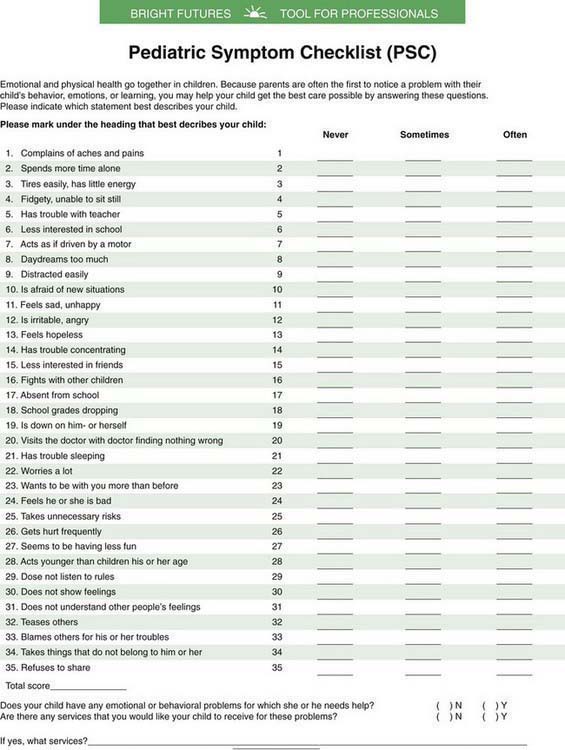

Clinicians are encouraged to become familiar with the psychometric characteristics and appropriate use of at least one broad-based measure of psychosocial problems, such as the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC) (Fig. 18-1), or the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham–IV (SNAP-IV). If the interview or broad-based rating scale suggests difficulties in one or more specific symptom areas, the clinician can follow with a psychometrically sound, appropriate narrow-based instrument such as the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT), the Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Rating Scale for attention and behavior problems, the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC) for depression, or the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) for anxiety.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the psychiatric assessment of infants and toddlers. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:21S-36S.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the psychiatric assessment of children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:4S-20S.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition, primary care. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1995.

Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, et al. The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:545-553.

Boris NW, Zeanah CH. Research diagnostic criteria for infants and preschool children: the process and empirical support. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:1504-1512.

Bourdon KH, Goodman R, Rae DS, et al. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: U.S. normative data and psychometric properties. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:557-564.

Cohen E, MacKenzie RG, Yates GL. HEADSS, a psychosocial risk assessment instrument: implications for designing effective intervention programs for runaway youth. J Adolesc Health. 1991;12:539-544.

Faulstich ME, Carey MP, Ruggiero L, et al. Assessment of depression in childhood and adolescence: an evaluation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC). Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:1024-1027.

Jellinek MS, Murphy JM, Little M, et al. Use of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist to screen for psychosocial problems in pediatric primary care: a national feasibility study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:254-260.

Robins DL. Screening for autism spectrum disorders in primary care settings. Autism. 2008;12:537-556.

Swanson J, Schuck S, Mann M. Categorical and dimensional definitions and evaluations of symptoms of ADHD: the SNAP and SWAN ratings scales (website). http://www.adhd.net, 2010. Accessed February 8

Wolraich ML, Feurer ID, Hannah JN, et al. Obtaining systematic teacher reports of disruptive behavior disorders utilizing DSM-IV. J Abn Child Psychol. 1998;26:141-152.

Zero to Three. Diagnostic classification of mental health and development disorders of infancy and early childhood: DC:0-3R. Washington, DC: Zero to Three; 1994.