CHAPTER 8 Assessing Outcomes After Hip Surgery

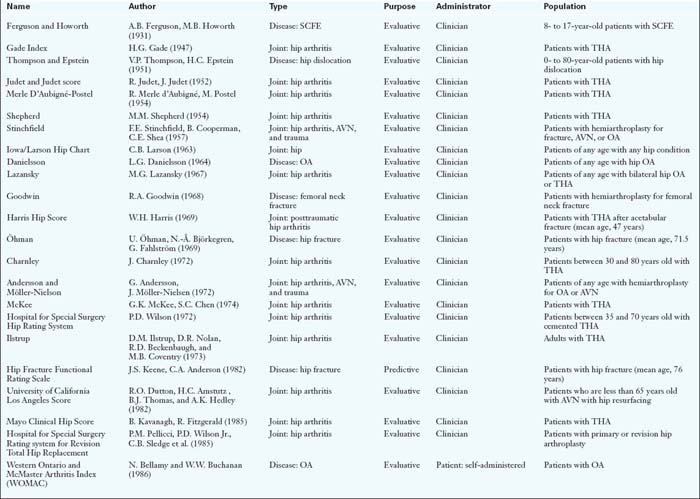

Classification (Table 8-1)

Psychometrics (Table 8-2)

Table 8-2 shows the evaluative tools that have been tested for reliability, validity, and responsiveness. Of the clinician-based tools, only the Harris Hip Score and Lequesne Index have been tested for reliability and shown to have internal consistency. Ten of the patient-based measures have demonstrated internal consistency. Two others—the Total Hip Arthroplasty Outcome Evaluation and the Hip Rating Questionnaire—have also been tested for internal consistency, but the results were poor. The majority of the questionnaires have demonstrated adequate reproducibility or test/retest reliability. All tools in Table 8-2 were presumed to have both face and content validity because patients and clinicians were involved in their creation or because they have been used by other surgeons in clinical practice or research. All have been tested for construct validity against other questionnaires. Only three tools have been tested for criterion validity: the Hip Rating Questionnaire was compared with the 6-minute walk test; the MFA was compared with stair climbing and walking speed; and the Lower-Extremity Measure was compared with the timed up-and-go test.

Recommendations

Annotated references and suggested readings

Amstutz H.C., Thomas B.J., Jinnah R., Kim W., Grogan T., Yale C. Treatment of primary osteoarthritis of the hip. A comparison of total joint and surface replacement arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(2):228-241.

Andersson G. Hip assessment: a comparison of nine different methods. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1972;54B:621-625.

Bach C.M., Feizelmeier H., Kaufmann G., Sununu T., Gobel G., Krismer M. Categorization diminishes the reliability of hip scores. Clin Orthop Relat Res (411); 2003:166-173.

Bellamy N., Buchanan W.W. A preliminary evaluation of the dimensionality and clinical importance of pain and disability in osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Clin Rheumatol. 1986;5(2):231-241.

Bellamy N., Buchanan W.W., Goldsmith C.H., Campbell J., Stitt L.W. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(12):1833-1840.

Boardman D.L., Dorey F., Thomas B.J., Lieberman J.R. The accuracy of assessing total hip arthroplasty outcomes: a retrospective correlation study of walking ability and 2 validated measurement devices. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15(2):200-204.

Bryant M.J., Kernohan W.G., Nixon J.R., Mollan R.AB. A statistical analysis of hip scores. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75–B(5):705-709.

Callaghan J.J., Dysart S.H., Savori C.G., Hopkinson W.J. Assessing the results of hip replacement: a comparison of five different rating systems. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72 B:1008-1009.

The authors compared the results of measuring outcomes in 100 patients who had received an uncemented total hip arthroplasty. They compared the five most frequently used rating systems (Hospital for Special Surgery; Mayo Clinical Hip Score; Iowa/Larson Rating scale for hip disabilities; Harris Hip Score; Merle d’Aubiné-Postel) to the patient’s impression of their hip in categories of excellent, good, fair, and poor. They stated that the Hospital for Special Surgery rating produced the most optimistic and the Merle d’Aubigné-Postel rating the most pessimistic.

They also compared the rating to Charnley’s functional classes to which no meaningful relationship was demonstrated. The authors concluded that functional class should be included in all rating systems and that descriptive words such as limp or pain should be used in precisely the same way, but provided no good evidence for this statement.

Charnley J. The long-term results of low-friction arthroplasty of the hip performed as a primary intervention. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1972;54(1):61-76.

Christensen C.P., Althausen P.L., Mittleman M.A., Lee J.A., McCarthy J.C. The nonarthritic hip score: reliable and validated. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;406:75-83.

Danielsson L.G. Incidence and prognosis of coxarthrosis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1964;66(Suppl):1-114.

D’Aubigné R.M., Postel M. Functional results of hip arthroplasty with acrylic prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1954;36-A(3):451-475.

Dawson J., Fitzpatrick R., Carr A., Murray D. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78(2):185-190.

Dawson J., Fitzpatrick R., Frost S., Gundle R., McLardy-Smith P., Murray D. Evidence for the validity of a patient-based instrument for assessment of outcome after revision hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(8):1125-1129.

Dutton R.O., Amstutz H.C., Thomas B.J., Hedley A.K. Tharies surface replacement for osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(8):1225-1237.

Engelberg R., Martin D.P., Agel J., Swiontkowski M.F. Musculoskeletal function assessment: reference values for patient and non-patient samples. J Orthop Res. 1999;17(1):101-109.

Ethgen O., Bruyere O., Richy F., Dardennes C., Reginster J.Y. Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(5):963-974.

Ferguson A.B., Howorth A.B. Slipping of the upper femoral epiphysis. JAMA. 1931;97(25):1867-1872.

Gade H.G. A contribution to the surgical treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip joint. A clinical study: comments on the follow up examinations and the evaluation of the therapeutic results. Acta Chir Scandinavica. 1947;120:37-45. Supplementum

Goodwin R.A. The Austin Moore prosthesis in fresh femoral neck fractures (A review of 611 post operative cases). Am J Orthop Surg. 1968;10(2):40-43.

Guyatt G.H., Bombardier C., Tugwell P.X. Measuring disease- specific quality of life in clinical trials. Cmaj. 1986;134(8):889-895.

Guyatt G.H., Feeny D.H., Patrick D.L. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med.. 1993;118(8):622-629.

Harris W.H. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51(4):737-755.

Hoeksma H.L., Van Den Ende C.H., Ronday H.K., Heering A., Breedveld F.C. Comparison of the responsiveness of the Harris Hip Score with generic measures for hip function in osteoarthritis of the hip. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(10):935-938.

Hopkins K.D. Educational and psychological measurement and evaluation, 8th ed. Allyn and Bacon: Toronto, 1998.

Hunsaker F.G., Cioffi D.A., Amadio P.C., Wright J.G., Caughlin B. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons outcomes instruments: normative values from the general population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A(2):208-215.

Ilstrup D.M., Nolan D.R., Beckenbaugh R.D., Coventry M.B. Factors influencing the results in 2,012 total hip arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res (95); 1973:250-262.

Jaglal S., Lakhani Z., Schatzker J. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the lower extremity measure for patients with a hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A(7):955-962.

Johanson N.A., Charlson M.E., Szatrowski T.P., Ranawat C.S. A self-administered hip-rating questionnaire for the assessment of outcome after total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(4):587-597.

Johanson N.A., Liang M.H., Daltroy L., Rudicel S., Richmond J. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons lower limb outcomes assessment instruments. Reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(5):902-909.

Judet R., Judet J. Technique and results with the acrylic femoral head prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1952;34-B(2):173-180.

Keene J.S., Anderson C.A. Hip fractures in the elderly. Discharge predictions with a functional rating scale. AMA. 1982;248(5):564-567.

Kirkley A., Griffin S. Development of disease-specific quality of life measurement tools. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(10):1121-1128.

Kirshner B., Guyatt G. A methodological framework for assessing health indices. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38(1):27-36.

Klassbo M., Larsson E., Mannevik E. Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score. An extension of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index. Scand J Rheumatol. 2003;32(1):46-51.

Larson C.B. Rating scale for hip disabilities. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1963;31:85-93.

Lazansky M.G. A method for grading hips. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1967;49(4):644-651.

Letournel E., Judet R. Fractures of the acetabulum. New York, London, Berlin. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 1993.

Lequesne M.G., Samson M. Indices of severity in osteoarthritis for weight bearing joints. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1991;27:16-18.

Liang M.H., Katz J.N., Phillips C., Sledge C., Cats-Baril W. The total hip arthroplasty outcome evaluation form of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Results of a nominal group process. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Task Force on Outcome Studies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(5):639-646.

Martin R.L. Hip Arthroscopy and Outcome Assessment. Operative Techniques in Orthopaedics. 2005;15:290-296.

Martin D.P., Engelberg R., Agel J., Snapp D., Swiontkowski M.F. Development of a musculoskeletal extremity health status instrument: the musculoskeletal function assessment instrument. J Orthop Res. 1996;14(2):173-181.

Martin D.P., Engelberg R., Agel J., Swiontkowski M.F. Comparison of the Musculoskeletal Function Assessment questionnaire with the Short Form-36, the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index, and the Sickness Impact Profile health-status measures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(9):1323-1335.

Martin R.L., Kelly B.T., Philippon M.J. Evidence of validity for the hip outcome score. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(12):1304-1311.

Martin R.L., Philippon MJ. Evidence of reliability and responsiveness for the Hip Outcome Score. Operative Techniques in Orthopaedics. 2005;15:290-296.

Martin R.L., Philippon M.J. Evidence of validity for the hip outcome score in hip arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(8):822-826.

Martin R.L., Philippon M.J. Evidence of reliability and responsive-ness for the hip outcome score. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(6):676-682.

Marx R.G., Jones E.C., Atwan N.C., Closkey R.F., Salvati E.A., Sculco T.P. Measuring improvement following total hip and knee arthroplasty using patient-based measures of outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(9):1999-2005.

Matta J.M., Mehne D.K., Roffi R. Fractures of the acetabulum. Early results of a prospective study. Clin Orthop Relat Res (205); 1986:241-250.

McDowell I., Newell C. Measuring health: a guide to rating scales and questionnaires. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Mohtadi N. Development and validation of the quality of life outcome measure (questionnaire) for chronic anterior cruciate ligament deficiency. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(3):350-359.

Mohtadi N.G., Pedersen M.E., Chan D. The creation of a hip outcome measure for young patients with hip disease. In: World Congress of Sports Trauma.. 2008 Hong Kong

Mohtadi N., Pedersen M.E., Mahorn D., Chan, Fredine J. Validation of the Hip Quality of Life Questionnaire. New York: International Hip Arthroscopy Association, 2009.

Nilsdotter A.K., Lohmander L.S., Klassbo M., Roos E.M. Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS)–validity and responsiveness in total hip replacement. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2003;4:10.

Ohman U., Bjorkegren N.A., Fahlstrom G. Fracture of the femoral neck. A five-year follow up. Acta Chir Scand. 1969;135(1):27-42.

Ovre S., Sandvik L., Madsen J.E., Roise O. Comparison of distribution, agreement and correlation between the original and modified Merle d’Aubigne-Postel Score and the Harris Hip Score after acetabular fracture treatment: moderate agreement, high ceiling effect and excellent correlation in 450 patients. Acta Orthop. 2005;76(6):796-802.

Parker M.J., Palmer C.R. A new mobility score for predicting mortality after hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75(5):797-798.

Pedersen M.E., Chan D., Mohtadi N.G. Hip outcome measures: A systematic review of the literature. In Alberta Orthopaedics Residents Day; 2006;. Red Deer, Alberta; 2006.

Pellicci P.M., Wilson P.D.Jr., Sledge C.B., Salvati E.A., Ranawat C.S., Poss R., et al. Long-term results of revision total hip replacement. A follow up report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(4):513-516.

Rat A.C., Coste J., Pouchot J., Baumann M., Spitz E., Retel-Rude N., et al. OAKHQOL: a new instrument to measure quality of life in knee and hip osteoarthritis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(1):47-55.

Rat A.C., Pouchot J., Coste J., Baumann C., Spitz E., Retel-Rude N., et al. Development and testing of a specific quality-of-life questionnaire for knee and hip osteoarthritis: OAKHQOL (OsteoArthritis of Knee Hip Quality Of Life). Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73(6):697-704.

Schmalzried T.P., Silva M., de la Rosa M.A., Choi E.S., Fowble V.A. Optimizing patient selection and outcomes with total hip resurfacing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;441:200-204.

Shepherd M.M. Assessment of function after arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1954;36B(3):354-363.

Shields R.K., Enloe L.J., Evans R.E., Smith K.B., Steckel S.D. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of functional tests in patients with total joint replacement. Phys Ther. 1995;75(3):169-176. discussion 176–179

Shimmin A.J., Bare J., Back D.L. Complications associated with hip resurfacing arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2005;36(2):187-193. ix

Soderman P., Malchau H. Is the Harris hip score system useful to study the outcome of total hip replacement?. Clin Orthop Relat Res (384); 2001:189-197.

Stucki G., Sangha O., Stucki S., Michel B.A., Tyndall A., Dick W., et al. Comparison of the WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities) osteoarthritis index and a self-report format of the self-administered Lequesne-Algofunctional index in patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1998;6(2):79-86.

Sullivan M., Karlsson J. The Swedish SF-36 Health Survey III. Evaluation of criterion-based validity: results from normative population. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1105-1113.

Tegner Y., Lysholm J. Rating systems in the evaluation of knee ligament injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res (198); 1985:43-49.

Theiler R., Sangha O., Schaeren S., Michel B.A., Tyndall A., Dick W., et al. Superior responsiveness of the pain and function sections of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) as compared to the Lequesne-Algofunctional Index in patients with osteoarthritis of the lower extremities. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1999;7(6):515-519.

Thompson V.P., Epstein H.C. Traumatic dislocation of the hip: a survey of two hundred and four cases covering a period of twenty-one years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1951;33(3):746-778.

Treacy R.B. To resurface or replace the hip in the under 65-year-old: the case of resurfacing. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88(4):349-353. discussion 349–353

Tugwell P., Bombardier C., Buchanan W.W., Goldsmith C.H., Grace E., Hanna B. The MACTAR Patient Preference Disability Questionnaire—an individualized functional priority approach for assessing improvement in physical disability in clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1987;14(3):446-451.

Verhoeven A.C., Boers M., van der Liden S. Validity of the MACTAR questionnaire as a functional index in a rheumatoid arthritis clinical trial. The McMaster Toronto Arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(12):2801-2809.

Ware J.Jr., Kosinski M., Keller S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220-233.

Wilson P.D.Jr., Amstutz H.C., Czerniecki A., Salvati E.A., Mendes DG. Total hip replacement with fixation by acrylic cement. A preliminary study of 100 consecutive McKee-Farrar prosthetic replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(2):207-236.

Wright J.G., Rudicel S., Feinstein A.R. Ask patients what they want. Evaluation of individual complaints before total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(2):229-234.

Wright J.G., Young N.L. A comparison of different indices of responsiveness. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(3):239-246.

Yano H., Sano S., Nagata Y., Tabuchi K., Okinaga S., Seki H., et al. Modified rotational acetabular osteotomy (RAO) for advanced osteoarthritis of the hip joint in the middle-aged person. First report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1990;109(3):121-125.

Zuckerman J.D., Koval K.J., Aharonoff G.B., Hiebert R., Skovron ML. A functional recovery score for elderly hip fracture patients: I. Development. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14(1):20-25.