CHAPTER 21 Arthroscopic Synovectomy and Treatment of Synovial Disorders

Imaging and diagnostic studies

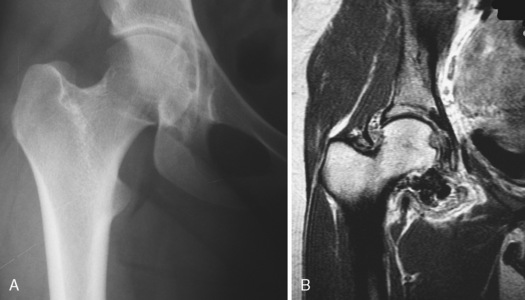

When evaluating a patient with symptoms that are consistent with hip joint pathology, plain radiographs should be obtained first. We typically obtain an anteroposterior radiograph of both hips with 2 cm to 4 cm between the pubic symphysis and the sacrococcygeal junction. A frog-leg lateral radiograph and a cross-table lateral radiograph with 15 degrees of internal rotation complete the initial series. Radiographic abnormalities may include arthritis, arthrosis, dysplasia, femoroacetabular impingement, and loose bodies. It has been reported that radiographs fail to diagnose loose bodies up to 50% of the time; this may be a result of the inconsistent calcification of these loose bodies and because they may be obscured by overlying structures. Large and multiple lucencies on plain radiographs are consistent with PVNS (Figure 21-1, A). Magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) is the gold standard imaging technique for evaluating the hip joint proper. MRA has been shown to be very sensitive for labral tears and less accurate for chondral pathology. Filling defects can indicate loose bodies, as has been seen with synovial chondromatosis. As a result of hemosiderin deposition, pigmented villonodular synovitis is seen as a spotty or extensive low-signal area within proliferative synovial masses on T1 and T2 images; this condition is best seen on fast-field echo-sequence MRA images (see Figure 21-1, B). MRA imaging will typically reveal an effusion and variable degrees of synovitis in the setting of an acute septic hip; an aspiration can also be performed as part of this imaging. Chronic infection with associated osteomyelitis and adjacent abscesses should be ruled out in this setting before arthroscopic hip irrigation and synovial debridement are performed. MRA has important applications for imaging the rheumatoid joint. Bony erosions are visualized with MRA during the early stages of rheumatoid arthritis, and they are frequently detected before they appear on plain radiographs. MRA also detects bone marrow edema, which is another important feature that is associated with inflammatory joint disease and that may be a forerunner of erosion. Synovial membrane inflammation and hypertrophy are detected after contrast enhancement and also with the use of dynamic MRA techniques, which provide a noninvasive method for accurately measuring the inflammatory process.

Indications

Surgical technique

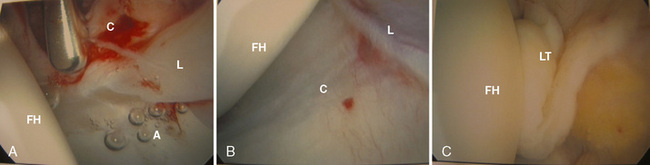

A spinal needle is placed at the level of the anterior paratrochanteric portal (i.e., just anterior to the proximal aspect of the greater trochanter), roughly parallel to the sourcil or the acetabular roof. Care is taken to not damage the femoral head articular cartilage and to place the needle between the labrum and the femoral head. The inner stylet is then removed, which releases the intra-articular negative pressure and allows for easier distractibility, if needed. A cannulated system is then used to introduce a blunt obturator into the joint over a guidewire, and this is followed by a 70-degree arthroscope. At this point, the anterior femoral head, the acetabulum, the acetabular labrum, and the anterior capsule are identified (Figure 21-4, A). An anterior portal 2 cm distal to the junction of the anterosuperior iliac spine and the proximal greater trochanter is made with the use of direct visualization. We make this portal farther distal than what is typically described, which allows for the better placement of anchors and for chondral work on the acetabulum without accessory portals when labral repair and/or chondroplasty procedures are indicated. A limited capsulotomy is then performed with a beaver blade to allow for improved maneuverability. At this point, the arthroscope is placed into the anterior portal looking back at the initial anterior paratrochanteric portal. If this portal has penetrated a portion of the labrum, then it is repositioned outside of the labrum and followed by a limited capsulotomy. The arthroscope is then placed back into the anterior paratrochanteric portal, and the superior and posterior portions of the femoral head, the labrum, and the acetabulum are visualized (see Figure 21-4, B). A spinal needle is placed in the posterior paratrochanteric portal initially for outflow; this portal can later be established as a working or arthroscopic portal if one is required for the procedure that is to be performed.

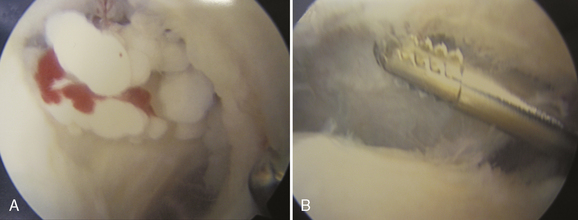

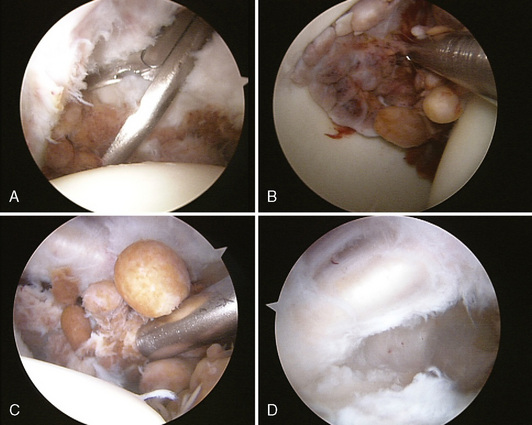

Next, a systematic evaluation of the central compartment is performed with the arthroscope initially in the anterior paratrochanteric portal. The anterior labrum, the medial femoral head, and the acetabular fossa with the associated ligamentum teres and pulvinar are evaluated (see Figure 21-4, C). External rotation of the hip should reveal a tightening of the ligamentum teres, if it is intact. Loose bodies, synovitis, and PVNS will frequently be found in the acetabular fossa when managing these synovial disorders. Occasionally a 30-degree arthroscope will allow for the better evaluation of the acetabular fossa. Loose bodies are then removed with various available graspers, and the pulvinar can be debrided with a shaver if it is pathologic. PVNS can be resistant to standard shaving, and a more aggressive grasper can be used to remove this tissue and to send the tissue for confirmatory biopsy. Switching the working and arthroscopic portals allows for complete access to this region for the removal of loose bodies and pathologic pulvinar or synovium.

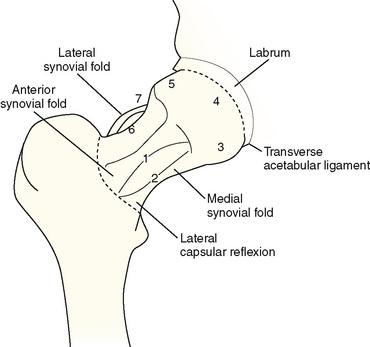

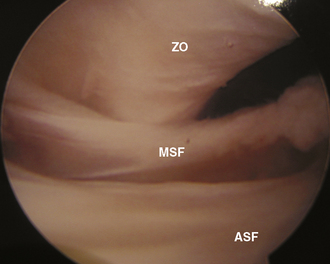

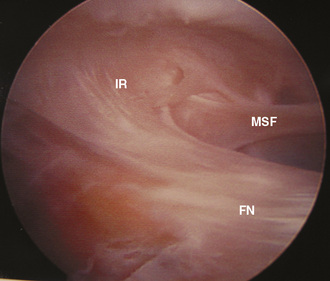

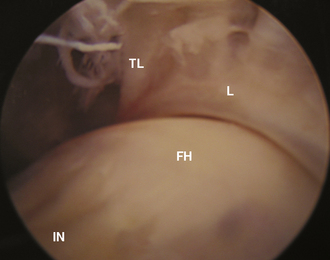

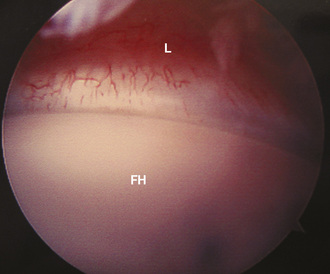

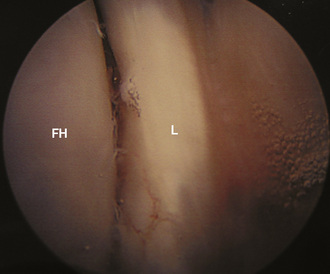

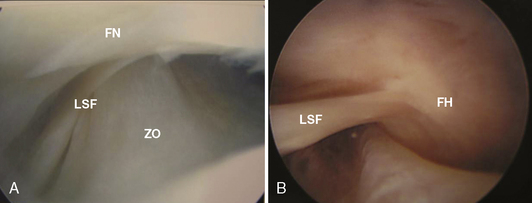

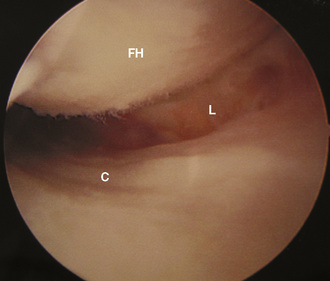

The peripheral compartment can be divided into seven distinct regions (Figure 21-5). We have modified this description on the basis of the evaluation of the anterior, posterior, inferior, superior, medial, and lateral anatomic regions as recently described by Ilizaliturri and colleagues. The anterior neck region is identified first with its associated anterior (adherent to the femoral neck) and medial synovial folds, zona orbicularis, and iliofemoral ligament (Figure 21-6). Looking further inferolaterally (caudally) reveals the inferior reflection of the capsule at the intertrochanteric crest (Figure 21-7). Moving the arthroscope farther inferior over the medial synovial fold reveals the inferior neck, the inferolateral femoral head, the anteroinferior labrum, and the transverse acetabular ligament (Figure 21-8). The arthroscope is then brought back superiorly to reveal the anterolateral femoral head and the anterior labrum (Figure 21-9). Looking farther superior will then bring the superolateral femoral head and superior labrum into view (Figure 21-10). The arthroscope is then brought down over the superior femoral neck, which brings the lateral synovial fold into view (Figure 21-11, A and B). The arthroscope is then brought between the zona orbicularis and the lateral synovial fold to view the posterior femoral neck, the posterolateral femoral head, and the posterior capsule (Figure 21-12). This completes the systematic evaluation of the peripheral compartment. Exchanging the 30- and 70-degree arthroscopes will allow for the visualization of all of these areas in most patients. The shaver and the arthroscope can be exchanged among the anterolateral, anterior, posterolateral, and mid-lateral portals to perform a near-complete peripheral compartment synovectomy. Varying degrees of flexion, abduction, and rotation and the occasional removal of the perineal post will assist with the visualization of the previously named regions.

Blitzer C.M. Arthroscopic management of septic arthritis of the hip. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(4):414-416.

Boyer T. Dorfmann H. Arthroscopy in primary synovial chondromatosis of the hip: description and outcome of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br Mar. 2008;90(3):314-318.

Cheng X.G., You Y.H., Liu W., Zhao T., Qu H. MRI features of pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS). Clin Rheumatol. 2004;23(1):31-34. Epub 2004 Jan 9

Chung W.K., Slater G.L., Bates E.H. Treatment of septic arthritis of the hip by arthroscopic lavage. J Pediatr Orthop. Jul-Aug 1993;13(4):444-446.

Cotton A., Flipo R.M., Chastaner P., et al. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip: review of radiographic features in 59 patients. Skeletal Radiol.. 1995;24(1):1-6.

Dienst M., Godde S., Seil R., Hammer D., Kohn D. Hip arthroscopy without traction: in vivo anatomy of the peripheral hip joint cavity. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(9):924-931.

Doward D.A., Troxell M.L., Fredericson M. Synovial chondromatosis in an elite cyclist; a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. Jun 2006;87(6):860-865.

Godde S., Kusma M., Dienst M. Synovial disorders and loose bodies in the hip joint. Arthroscopic diagnostics and treatment. Orthopade. 2006;35(1):67-76.

Ilizaliturri V., Byrd J.W., Sampson T., Larson C.M., et al. A geographic zone method to describe intra-articular pathology in hip arthroscopy: cadaveric study and preliminary report. Arthroscopy. May 2008;24(5):534-539.

Kelly B.T., Williams R.J.3rd, Philippon M.J. Hip arthroscopy: current indications, treatment options, and management issues. Am J Sports Med.. 2003;31(6):1020-1037.

Kim S.J., Choi N.H., Ko S.H., Linton J.A., Park H.W. Arthroscopic treatment of septic arthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (407); 2003:211-214.

Krebs V.E. The role of hip arthroscopy in the treatment of synovial disorders and loose bodies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (406); 2003:48-59.

McQueen M.F. MRI imaging in early inflammatory arthritis: what is its role. Rheumatology. 2000;39:700-706.

Nusem I., Jabut M.K., Playford E.G. Arthroscopic treatment of septic arthritis of the hip. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(8):902. e1–e3

Shabat S., Kollender Y., Merimsky O., et al. The use of surgery and yttrium 90 in the management of extensive and diffuse pigmented villonodular synovitis of large joints. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002;41(10):1113-1118.

Yamamoto Y., Ide Y., Hachisuka N., Maekawa S., Akamatsu N. Arthroscopic surgery for septic arthritis of the hip joint in 4 adults. Arthroscopy. Mar 2001;17(3):290-297.