CHAPTER 52 Arthroscopic Release of Wrist Contracture

Rationale and Basic Science Pertinent to the Procedure

In refractory cases, surgical intervention may be warranted given the effectiveness of the technique when used with other joints.1–5 Open and arthroscopic techniques have been described for the wrist, although there is a paucity of literature regarding clinical outcomes. Nonetheless, for cases where conservative management is inadequate, there seems to be a role for surgical management. In cases in which the source of the restriction in motion is the capsule, release or resection of the capsule would provide an increased range of motion, much as it does in other cases of arthrofibrosis.

Anatomy

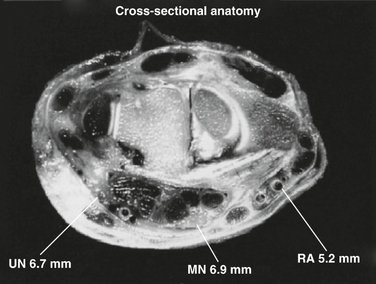

Numerous nerves and blood vessels traverse the wrist joint. Their proximity is important in choosing arthroscopic portals and during release of contractures. The ulnar and median nerves and the radial artery are most at risk during this procedure, and their proximity to the capsule is relevant to the safety of the release (Fig. 52-1).

Ulnar Nerve

The ulnar nerve has two significant superficial branches, which originate approximately 10 cm proximal to the wrist joint—the dorsal cutaneous branch, and the volar cutaneous branches of the ulnar nerve. Placement of the 6R portal should be done using blunt dissection to avoid injury to the dorsal superficial ulnar cutaneous nerve. The portal should be placed in the proximal fifth (19%) of an imaginary line drawn from the ulnar styloid to the fourth web space.6

Median Nerve

The median nerve’s course on the central volar aspect of the wrist within the carpal tunnel places it away from the joint capsule. It is the most superficial structure within the carpal tunnel and sits 13 mm underneath the skin surface.7 It passes an average of 6.9 mm volar to the volar wrist capsule and at closest, 4 mm.8 The median nerve passes radially within the carpal tunnel and is, on average, 18 mm radial to the pisiform and 8 mm ulnar to the scaphoid tubercle. It is protected by the mass of the finger flexors during capsular excision.

Surgical Technique

A standard arthroscopic setup is used.9 The patient is supine, with a tourniquet and finger traps. A 5-kg weight to distract the joint is used to assist in visualization. A 2.7-mm arthroscope is used in most cases, although a 1.9-mm arthroscope can be used in a smaller or more restricted joint. Using the 3,4 and 6R working portals, diagnostic arthroscopy and débridement are performed.

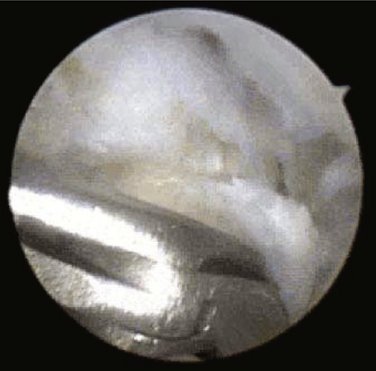

Volar Capsular Release

There is often synovitis on the volar capsule that should be débrided to improve visualization and make subsequent capsular release easier. To perform the capsular release, a hooked electrocautery probe is introduced through the 6R portal and advanced in a radial direction as far as possible. Cautery is used to divide the volar capsule and volar carpal ligaments as shown in Figure 52-2. The long and short radiolunate ligaments, the radiocapitate ligament, and part of the radioscapholunate ligament are divided. Figure 52-2 also shows the division of the volar capsule down to periarticular fat. Based on the work of Viegas and colleagues,10 the authors believe that leaving part of the radioscaphocapitate ligament intact is important to prevent the potential complication of ulnar translocation of the carpus. We have not seen this complication, but predict that it could occur, and that it would be extremely difficult to treat.

The triangular fibrocartilaginous complex is left intact, including the ulnotriquetral and ulnolunate ligaments. Division of the radial side of the volar capsule should continue until the flexor carpi radialis tendon is seen, and extracapsular fat is exposed. The surgeon must not delve into this volar periarticular fat because this may lead to significant neurovascular injury. Distances to important anatomical structures are shown in Table 52-1. Although the median and ulnar nerves are at least 4 mm away from the capsule, the radial artery can lie as close as 3 mm to the radial volar capsule.

TABLE 52-1 Distance from the Radiocarpal Joint Capsule: Results from Magnetic Resonance Imaging Scans and Cadaver Sections

| Structure | Average (mm) | Range (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Median nerve | 6.9 | 4-9 |

| Ulnar nerve | 6.7 | 4-9 |

| Radial artery | 5.2 | 3-7 |

Dorsal Capsular Release

Our preferred technique for dorsal capsular release is to use a volar radial portal as a viewing portal as described by Slutsky, Ashwood, and Abe and their colleagues,11–13 and the 3,4 dorsal portal as a working portal. Blunt dissection using a hemostat is used to pass a nylon tape through the 3,4 portal, down to the level of the tendon-capsule interface and across to the 6R portal. By applying tension to the nylon tape, it can be used as a retractor to protect the tendons from injury during release of the dorsal capsule. The nylon tape is positioned between the capsule and extensor tendons.

The capsule is excised using basket forceps with one jaw visualized intra-articularly and the other jaw placed between the capsule and the nylon tape retracting the tendons as shown in Figure 52-3. The capsulectomy proceeds from the 3,4 portal, ulnarly to the point of the 6R portal. The use of the basket forceps to release the dorsal capsule down to the level of the tendon-capsule interface, at which the retracting nylon tape is seen.

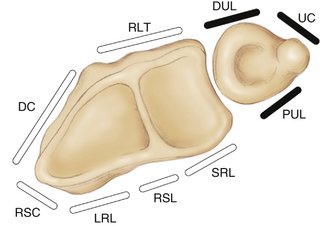

Figure 52-4 shows a summary of the ligaments to be divided during either a volar or a dorsal procedure. Following either procedure, a gentle closed manipulation is performed.

Results

Wrist contracture is an uncommon problem, and cases that are refractory to conservative management make up an even smaller cohort. There are only two case series in the literature that describe any form of arthroscopic release of the wrist. The first is an article that describes the technique as presented here. Patients with a range of motion less than the functional range described by Palmer and colleagues14 were treated with the capsular release as described previously. The range of motion increased from 20% to 70% of the contralateral side, and the grip strength increased from one third to more than two thirds of the contralateral side.8 This improvement in grip strength is due to better wrist extension, which facilitates grip function.

A second article describes arthroscopic release of a scapholunate sagittally oriented curtain of tissue found between the scapholunate interval and the midradial ridge.15 Although we did not see this feature in our series, if such a structure is found, it should be débrided. Hattori and associates15 found that after débridement of this band of tissue, improvements in range of motion were seen.

1. Richmond JC, Gladstone J, MacGillivray J. Continuous passive motion after arthroscopically assisted anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: comparison of short- versus long-term use. Arthroscopy. 1991;7:39-44.

2. Jones GS, Savoie FH3rd. Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:277-283.

3. Vaquero J, Vidal C, Medina E, et al. Arthroscopic lysis in knee arthrofibrosis. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:691-694.

4. Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Biggs DJ, Fitsialos DP, et al. The resistant frozen shoulder: manipulation versus arthroscopic release. Clin Orthop.. 1995;319:238-248.

5. Utsugi K, Sakai H, Hiraoka H, et al. Intra-articular fibrous tissue formation following ankle fracture: the significance of arthroscopic debridement of fibrous tissue. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:89-93.

6. Tindall A, Patel M, Frost A, et al. The anatomy of the dorsal cutaneous branch of the ulnar nerve—a safe zone for positioning of the 6R portal in wrist arthroscopy. J Hand Surg [Br]. 2006;31:203-205.

7. Sora MC, Genser-Strobl B. The sectional anatomy of the carpal tunnel and its related neurovascular structures studied by using plastination. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12:380-384.

8. Verhellen R, Bain GI. Arthroscopic capsular release for contracture of the wrist: a new technique. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:106-110.

9. Bain GI, Richards RS, Roth JH. Wrist arthroscopy. In Lichtman DM, Alexander AH, editors: The Wrist and Its Disorders, 2nd ed, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1997.

10. Viegas SF, Patterson RM, Ward K. Extrinsic wrist ligaments in the pathomechanics of ulnar translation instability. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1995;20:312-318.

11. Slutsky DJ. Wrist arthroscopy through a volar radial portal. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:624-630.

12. Ashwood N, Bain GI. Arthroscopically assisted treatment of intraosseous ganglions of the lunate: a new technique. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2003;28:62-68.

13. Abe Y, Doi K, Hattori Y, et al. Arthroscopic assessment of the volar region of the scapholunate interosseous ligament through a volar portal. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2003;28:69-73.

14. Palmer AK, Werner FW, Murphy D, et al. Functional wrist motion: A biochemical study. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1985;10:39-46.

15. Hattori T, Tsunoda K, Watanabe K, et al. Arthroscopic mobilization for contracture of the wrist. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:850-854.