CHAPTER 24 Arthroscopic Management of the Trauma Patient

Introduction

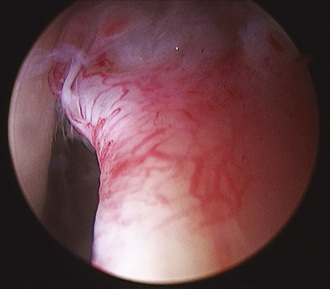

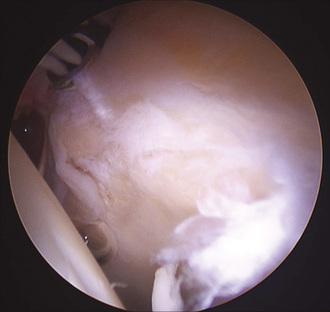

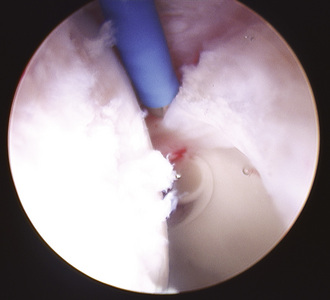

Hip arthroscopy has been described as part of treatment regimens for hip trauma and related sequelae for decades, but the role of hip arthroscopy for this application has expanded rapidly during recent years. As early as 1931, Burman noted a role for a form of hip arthroscopy for loose body or fragment removal. The role for surgical debridement of the hip expanded substantially with the observation that loose bodies were ubiquitous with hip fracture dislocations. Epstein advised that all hip fracture–dislocations should be treated with debridement in an attempt to delay the appearance of traumatic arthritis and to minimize its severity. He advocated open debridement rather than arthroscopic debridement. The prevalence of loose bodies after injury to the hip and their impact on the development of hip joint arthrosis certainly contributed to the imperfect long-term results of dislocations and fractures around the hip joint (Figures 24-1 and 24-2). Until recently, loose bone and cartilage fragments were almost always retrieved with open arthrotomy. Advances in arthroscopic tools and techniques have made arthroscopic loose-body removal highly efficient. Arthroscopy advantages include diminished blood loss, smaller incisions, decreased recovery time, reduced potential for neurovascular damage, and decreased disruption of capsuloligamentous structures. Indications for arthroscopic debridement after trauma have been extended to include the extraction of bullets, the removal of broken hardware from the joint, and joint lavage for the treatment of infection or contamination in association with bullet fragments passing through the bowel and communicating with the hip joint.

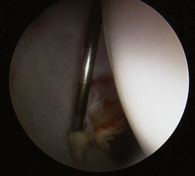

Figure 24–2 Another view of the same patient shown in Figure 24-1. Femoral head chondrolysis is evident. Intervention was limited to labral debridement, chondroplasty of the femoral head, and lavage.

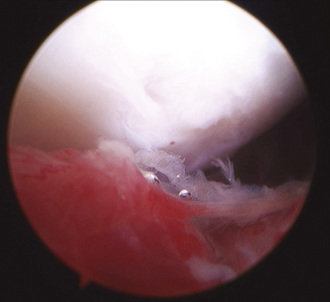

The arthroscopic treatment of acetabular labral pathology most typically involves atraumatic tears or labral disease associated with impingement or hip dysplasia. Isolated cases of traumatic labral pathology have been reported since 1959, when Dameron described a bucket-handle tear of the acetabular labrum that prohibited the reduction of a posterior dislocation of the hip that subsequently required open repair. Labral injury has more recently been described as a relatively common but previously poorly recognized phenomenon in association with acetabular fractures. Ganz described reproducible labral pathology in 14 patients with displaced transverse acetabular fractures who had been treated with open reduction and internal fixation. The labrum was partially or completely detached from the superior acetabular rim in all cases. In this series, an avulsed portion of the labrum was left if it was stable and undamaged, resected if it was unstable and damaged, and repaired if it was unstable but intact or attached to a bony fragment. Ganz proposed arthrotomy at the time of acetabular fracture fixation to search for associated intracapsular injuries in displaced transverse acetabular fractures and to treat injuries accordingly. In the case of acetabular fractures, multiple authors have identified reduction as the most important factor for avoiding the development of arthrosis and for obtaining a good clinical outcome, but they have noted that even anatomic fracture reduction fails to guarantee excellent outcomes. It is likely that additional factors such as chondral damage at the time of injury, loose fragments, and labral injuries all contribute to the patient’s final long-term outcome (Figures 24-3 and 24-4).

Surgical technique

Technical Pearls

Results and outcomes

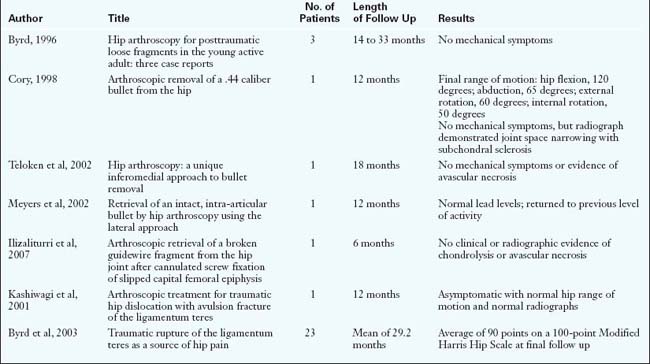

The majority of results for hip arthroscopy performed for traumatic injuries are extracted from case reports, which typically have minimal follow up (Table 24-1). Keene and Villar described two cases of posterior hip dislocation with the successful removal of retained loose bodies with hip arthroscopy. Byrd described three cases of hip arthroscopy for the management of posttraumatic loose fragments. At 14 to 33 months of follow up, each case had a reportedly successful outcome with no mechanical symptoms. Svoboda discussed a case of loose-body removal from a posterior hip dislocation in a 23-year-old military recruit that was confirmed with a postoperative CT scan. Mullis reported about 36 patients with either a simple dislocation, a fracture dislocation, or a wall fracture. When arthroscopy was performed, 92% of these patients were found to have loose bodies. Interestingly, loose bodies were found even in 7 of the 9 patients in which standard radiographic studies (anteroposterior pelvic imaging and CT scanning) failed to demonstrate them.

Violent trauma to the hip, including dislocations, is frequently associated with injury or rupture of the ligamentum teres (Figure 24-5). Isolated injuries may present a diagnostic challenge. In 2001, Kashiwagi published a case report of a 10-year-old girl who fell awkwardly from a swing onto her leg, which resulted in an avulsion of the ligamentum teres from its acetabular attachment. The patient presented with pain and the inability to bear weight on the affected leg. On physical examination, her hip lay in an abducted position, with limited range of motion. Radiographs demonstrated a slightly widened joint space, and a CT scan confirmed a bone fragment that was associated with the avulsed ligamentum teres. The patient was treated with hip arthroscopy, and the osteochondral fragment was removed from the anterior portal using forceps. The girl was asymptomatic with a full range of hip motion and no abnormal radiographic findings at 1 year postoperatively. Byrd treated 23 patients with traumatic injuries to the ligamentum teres (15 violent injuries, including 6 dislocations and 8 twisting injuries). The duration of symptoms averaged 28.5 months and included deep anterior groin pain in all patients; 19 patients had mechanical symptoms, and 4 patients had pain during activity. On examination, 15 patients had pain during logrolling of the hip, whereas 23 had pain with maximal flexion and internal rotation. Upon intervention, it was found that 12 patients had complete ruptures and that 11 had partial tears. Most commonly, there was associated pathology (9 labral tears, 5 loose bodies, 5 chondral injuries). The average preoperative Modified Harris Hip Score of 47 improved to 90 postoperatively.

Annotated references and suggested readings

Bartlett C.S., DiFelice G.S., Buly R.L., Quinn T.J., Green D.S., Helfet D.L. Cardiac arrest as a result of intraabdominal extravasation of fluid during arthroscopic removal of a loose body from the hip joint of a patient with an acetabular fracture. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12(4):294-299.

Burman M.S. Arthroscopy or the direct visualization of joints: an experimental cadaver study. J Bone Joint Surg. 1931;13:669-695.

Byrd J.W. Hip arthroscopy for post-traumatic loose fragments in the young adult: three case reports. Clin J Sport Med. 1996;6:129-134.

Byrd J.W., Jones K.S. Traumatic rupture of the ligamentum teres as a source of hip pain. Arthroscopy. 2003;20(4):385-391.

Clarke M.T., Arora A., Villar R.N. Hip arthroscopy: complications in 1054 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res (406); 2003:84-88.

Cory J.W., Ruch D.S. Arthroscopic removal of a .44 caliber bullet from the hip. Arthroscopy. 1998;14(6):624-626.

Dameron T.B.Jr. Bucket-handle tear of acetabular labrum accompanying posterior dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg. 1959;41-A:131-134.

Epstein H.C. Posterior fracture-dislocations of the hip; long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56:1103-1127.

Funke E.L., Munzinger U. Complications in hip arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1996;12(2):156-159.

Griffin D.R., Villar R.N. Complications of arthroscopy of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(4):604-606.

Goldman A., Minkoff J., Price A., Krinick R. A posterior arthroscopic approach to bullet extraction from the hip. J Trauma. 1987;27(11):1294-1300.

Ilizaliturri V.M.Jr, Zarate-Kalfopulos B., Martinez-Escalante F.A., Cuevas-Olivo R., Camacho-Galindo J. Arthroscopic retrieval of a broken guidewire fragment from the hip joint after cannulated screw fixation of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(2):227.e1-227.e4. Epub 2006 Sep 11

Judet R., Judet J., Letournel E. Fractures of the acetabulum: classification and surgical approaches for open reduction—preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1964;46:1615-1646.

Kashiwagi N., Suzuki S., Seto Y. Arthroscopic treatment for traumatic hip dislocation with avulsion fracture of the ligamentum teres. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(1):67-69.

Keene G.S., Villar R.N. Arthroscopic loose body retrieval following traumatic hip dislocation. Injury. 1994;25:507-510.

Lee G.H., Virkus W.W., Kapotas J.S. Arthroscopically assisted minimally invasive intraarticular bullet extraction: technique, indications, and results. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;56:513-516.

Leunig M., Sledge J.B., Gill T.J., Ganz R. Traumatic labral avulsion from the stable rim: a constant pathology in displaced transverse acetabular fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2003;123(8):392-395.

Lu K.H. Arthroscopically assisted replacement of dynamic hip screw for unrecognized joint penetration of lag screw through a new portal. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(2):201-205.

Meyer N.J., Thiel B., Ninomiya J.T. Retrieval of an intact, intraarticular bullet by hip arthroscopy using the lateral approach. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16(1):51-53.

Mullis B.H., Dahners L.E. Hip arthroscopy to remove loose bodies after traumatic dislocation. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(1):22-26.

Philippon M.J., Schenker M.L., Briggs K.K., Maxwell R.B. Can microfracture produce repair tissue in acetabular chondral defects? Arthroscopy. 2008;24:46-50.

Sampson T.G. Complications of hip arthroscopy. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20(4):831-835.

Singleton S.B., Joshi A., Schwartz M.A., Collinge C.A. Arthroscopic bullet removal from the acetabulum. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(3):360-364.

Svoboda S.J., Williams D.M., Murphy K.P. Hip arthroscopy for osteochondral loose body removal after a posterior hip dislocation. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:777-781.

Teloken M.A., Schmietd I., Tomlinson D.P. Hip arthroscopy: a unique inferomedial approach to bullet removal. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(4):E21.

Upadhyay S.S., Moulton A. The long-term results of traumatic posterior dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63B:548-1541.

Watson D., Walcott-Sapp S., Westrich G. Symptomatic labral tear post femoral shaft fracture: case report. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21:731-733.

Yamamoto Y., Ide T., Ono T., Hamada Y. Usefulness of arthroscopic surgery in hip trauma cases. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:269-273.