CHAPTER 40 Arthroscopic Management of the Stiff Elbow

THE NONARTHRITIC STIFF ELBOW

PATHOLOGY OF ELBOW STIFFNESS (ARTHROFIBROSIS)

Arthrofibrosis of the elbow is defined as a loss of both extension and flexion of the elbow due to intrinsic and extrinsic abnormalities produced by fractures, dislocations, arthritic conditions, burns, head injury, or cerebral palsy.5,13,24,49,52,55 Intrinsic factors include intra-articular damage, fractures, loose bodies, synovitis, and foreign bodies whereas extrinsic factors include contractures due to scarring of the capsule or collateral ligaments, flexor or extensor musculature, instability, heterotopic bone, and skin contractures. Peripheral problems including head injuries, cerebral palsy, and neurologic dysfunction may also result in muscular contracture and spasticity with resultant loss of motion.

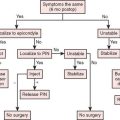

In managing a patient with contracture of the elbow, all etiologies must be considered before treatment. Patients with skin contracture or muscle spasticity must obviously be managed in a different fashion from those with intra-articular fracture or arthritic conditions. Commonly, more than one problem is involved in producing a stiff elbow. Each should be evaluated and managed appropriately. Arthroscopic treatment of flexion contracture of the elbow allows the surgeon to address the intrinsic intra-articular causes of elbow contracture, as well as those extrinsic causes that may be safely reached by this technique, including capsular and collateral ligament damage as well as problems with the extensor musculature. The risk of nerve injury, including post-erior interosseous nerve and ulnar nerve injury, is real in these stiff elbows and should be considered by the operative surgeon before undertaking arthroscopic management of this condition. Additionally, in the most contracted elbows, the restoration of motion may also produce late problems with the surrounding nerves, specifically the ulnar nerve. This complication of tardy ulnar nerve palsy may be prevented by arthroscopic or open ulnar nerve release at the time of the index surgery to restore motion (Box 40-1).

HISTORY OF ARTHROSCOPIC MANAGEMENT OF THE STIFF ELBOW

In 1931 and 1932, Burman6,7 described the use of the arthroscope in cadaveric elbow specimens. The use of arthroscopic techniques for the elbow lagged behind the knee and shoulder until the 1980s, during which time Andrews and Carson2 and Poehling et al48 reported on techniques for supine and prone arthroscopy. The 1990s brought about more work in elbow arthroscopy, with pioneering articles presented by O’Driscoll and Morrey, Baker, and McGinty.3,45 The first reports on the arthroscopic treatment of stiff elbows were by Nowicki and Shall,44 Jones and Savoie,27 and Byrd9 in the early 1990s. As techniques evolved, more reports by Kelly et al, Timmerman and Andrews, Ball et al and numer-ous others were presented.4,29,61 The works of O’Driscoll and Savoie spearheaded the advance of improved safety and surgical techniques that led to both improved results and expanded indications. Sporadic reports of neurologic injuries have occurred, emphasizing the need for caution and experience when dealing with these difficult problems.19,27,39

INDICATIONS FOR TREATMENT

Loss of motion of the elbow may cause significant morbidity.16,65 The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons defines normal flexion of the elbow as 0 to 146 degrees of flexion.65 In 1981 Morrey et al42 defined a functional arc of motion of the elbow as 30 to 130 degrees of flexion. This 100-degree arc of motion is the arc in which most activities of daily living (ADLs) are performed, and motion less than this results in an inability to perform even minimal ADLs. Certain activities may require more motion, including tying shoes, eating, personal hygiene, and sporting activities. Treatment is indicated for those contractures with a loss of extension of 30 degrees of motion, a loss of flexion of similar nature, and in those patients in whom a greater range of motion is required. As in all areas of the body, pain and functional impairment refractory to nonoperative management represent the primary indication for surgical treatment.

ETIOLOGY

The loss of motion in arthrofibrosis centers around soft tissue trauma,62 an injury, or a disease process that produces a synovitic reaction, hemorrhage, and inflammation of the capsule. In arthrofibrosis, the capsular tissues respond to this by thickening and becoming rigid. Attempts to aggressively stretch the capsule produces tearing, creating more hemorrhage and increased stiffness. The elbow is held in a flexed position to accommodate the hemarthrosis and the painful swelling in the capsular tissues. Physical therapy and splinting in this inflammatory phase may actually result in worsening conditions rather than improvement because of the repeated damage inflicted upon the capsule. Collateral ligament injury can further contribute to elbow contracture by allowing abnormal movement, producing further pressure on the damaged capsule.8,18,40,62 Additional problems occur with the scarring between the triceps tendon and the humerus, restricting flexion and extension by its tethering effect. This effect is more noticeable in the post-traumatic contractures and seems to be especially prevalent after open reduction internal fixation of periarticular fractures of the elbow.

Post-traumatic arthrofibrosis of the elbow may also be secondary to other intra-articular causes. Fractures and osteochondral lesions, articular incongruities, loose bodies, and foreign material may stimulate an inflammatory response in the capsule and result in a mechanical limitation to elbow motion. On the lateral side of the joint, this is often caused by residual deformity in the capitellum, radial fossa, or radial head following osteochondritis or trauma.26 On the medial side of the joint, a more congruous relationship of articular surface exists. Less severe injures to the coronoid or olecranon may produce bony incongruity, resulting in a painful arc of motion and subsequent loss of motion.

The specific components of arthrofibrosis may vary according to the mechanism of injury and postinjury treatment.50,60 Each factor must be considered in managing the arthrofibrotic elbow.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Management options for the contracted elbow include both conservative and surgical management. All patients with this disorder should undergo an extended trial of nonoperative therapy before surgery is considered. Selective Celestone injections, protected range of motion using a double-hinged elbow brace, and physical therapy including gentle stretching, icing, and joint mobilization, may prove to be beneficial.11,17 Static splinting is often helpful in obtaining a function arc of motion in the elbow. Caution should always be exercised during therapy to prevent additional capsular damage and worsening of the arthrofibrotic condition.

INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY

In the past, several authors have described open surgical release techniques for correction of elbow flexion contractures. These techniques include osteotomy of the medial epicondyle with complete anterior capsulectomy and lengthening of the biceps, limited lateral approach with capsulotomy, limited medial approach, and extensive posterior approach.16,65 Urbaniek and associates64 found a decrease in preoperative flexion contracture from 48 to 19 degrees with a lateral approach. Husband and Hastings25 found extension improved from a mean of 45 degrees preoperatively to 12 degrees postoperatively and flexion increased from 116 degrees to 129 degrees.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE: AUTHORS’ PREFERRED METHOD

The arthroscopic setup for surgical release of the elbow flexion contracture is that of a standard elbow arthroscopy (Box 40-2). A 4.5-mm arthroscope and shaver are used along with standard camera and video recording equipment. We prefer the prone position because it allows better access to both the anterior and posterior capsular structures, but certainly either the lateral decubitus or supine position can be used at the surgeon’s preference. In patients in whom there is quite a bit of scarring around the ulnar nerve or the posterior interosseous nerve, each of these may be approached through a small incision and a Penrose drain used to surround the nerve before attempting arthroscopy to protect the nerve from possible intraoperative damage. Indications for doing this include anteriorly displaced radial head fractures and anterior heterotopic bone for the posterior interosseous nerve, and large osteophytes and extra-articular fragments over the ulnar nerve. If this is deemed necessary by the preoperative evaluation, the posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) is approached through the transbrachioradialis approach of Lister with minimal damage to the surrounding musculature. The ulnar nerve is approached through a small incision posterior to the medial epicondyle. In each case, the arthroscopy can still be accomplished but with an increased margin of safety. The author usually prefers to attempt to expose the nerve arthroscopically in most cases but will use one of the above-mentioned approaches immediately if there is any distortion of normal anatomy near the normal course of the nerve.

BOX 40-2 Steps in Arthroscopic Management of the Arthrofibrotic Elbow

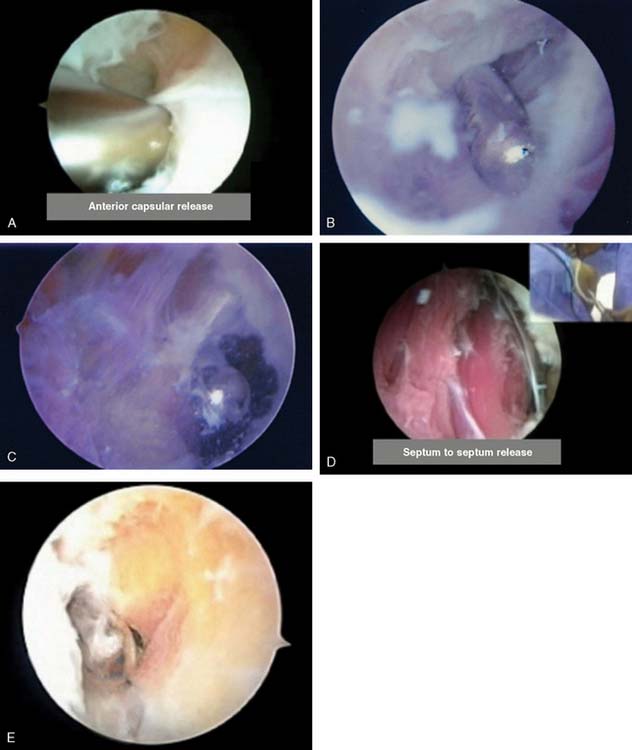

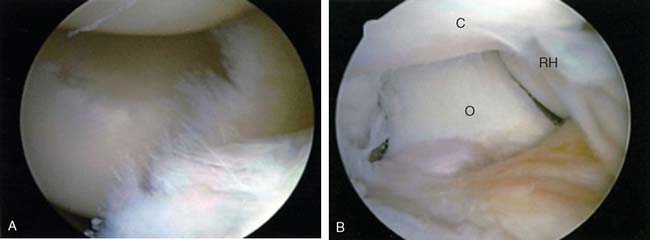

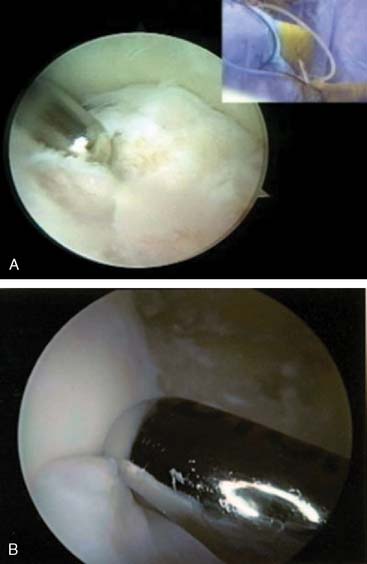

The initial attempt to insufflate the elbow is made through a standard soft spot portal, entering the joint between the radial head, capitellum, and ulna. A proximal anterior medial portal is then established using a blunt trocar only. The arthroscope is introduced through this canula, and the anterior compartment of the elbow is evaluated (Fig. 40-1). A proximal anterolateral portal is then established via an outside-in technique. The use of proximal portals to begin the procedure adds an anatomic protective factor to assist in the prevention of inadvertent neurologic damage. The more distal anterior lateral and anterior medial portals may be established once the joint and anatomy are better defined. These are useful for both retraction and for protection. Débridement of the anterior structures is then accomplished and an anterior capsular excision is performed (Fig. 40-2A to D). Excision of the capsule usually begins with the shaver in the medial portal. The capsule is excised beginning with the humeral attachment and continuing distally while remaining on the medial side of the joint until brachialis muscle fibers can be visualized (see Fig. 40-2A and B). The dissection progresses back toward the medial septum until the flexor pronator origin can be seen. The excision then continues laterally to the radial side of the joint. The scope is then placed in the medial portal and similarly from proximal to distal the capsule is excised to the lateral extensor muscle origin (see Fig. 40-2A to D). On completion of the anterior capsulectomy, the brachialis muscle should be visualized from the lateral to the medial intermuscular septum. Extension of the elbow is attempted, and range of motion is evaluated. The bone architecture is then reassessed for the need to restore the radial fossa, excise the radial head or excise part of the coronoid (see section on arthritis for the specifics of these techniques).

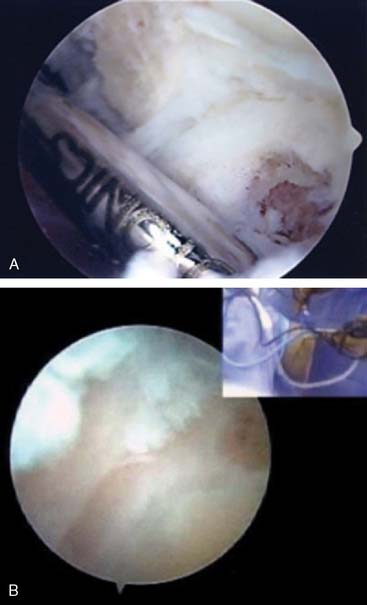

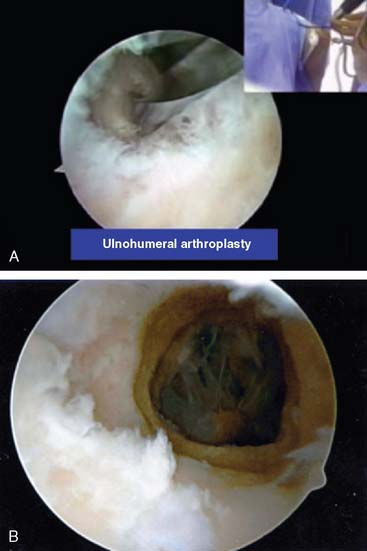

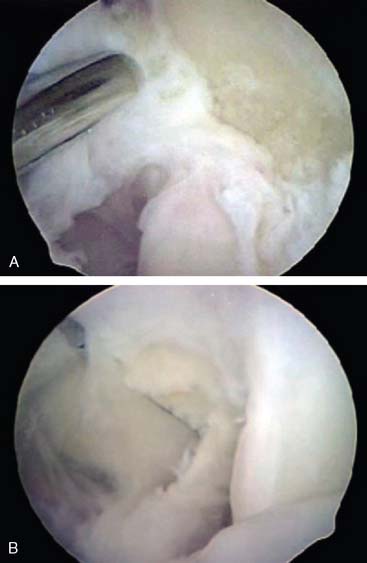

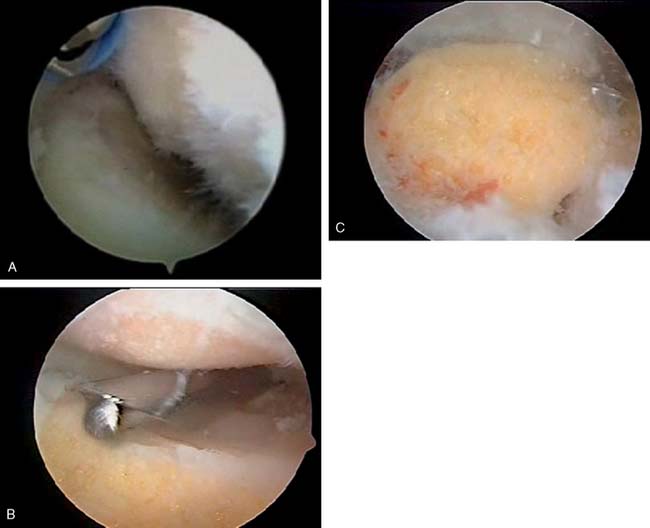

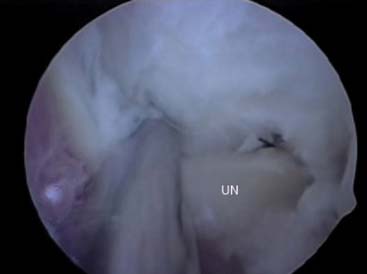

The arthroscope is then transferred to a posterior central and proximal posterolateral portal (Fig. 40-3A and B). The triceps is elevated off the distal humerus, and the olecranon fossa is débrided (Fig. 40-4). An ulnohumeral arthroplasty may be performed at this point, connecting the olecranon and coronoid fossa to allow improved flexion and extension and to diminish the risk of recurrent stiffness (Fig. 40-5). The medial gutter is then débrided of all loose bodies, joint adhesions, and osteophytes while protecting the ulnar nerve (Fig. 40-6A). The more severe the preoperative stiffness, the more necessary it may be to expose the ulnar nerve, either arthroscopically (see Fig. 40-6B) or open. The lateral gutter is then débrided as well, the posterolateral plica excised and synovitis, which is common in this area, also removed (Fig. 40-7A and B). Motion is then attempted again, and at this time, full flexion and extension should have been achieved. A drain is then inserted anteriorly, a pain pump is inserted posteriorly, and the patient is placed in a soft dressing.

RESULTS

The arthroscopic management of arthrofibrosis has continued since the initial report by Jones and Savoie.27 Extension of the elbow increased from 46 degrees to 5 degrees, and flexion increased 96 degrees to 138 degrees. Recent reports by Timmerman et al,61 Lapner et al,31 Ball et al,4 and Nguyen et al43 have described the effectiveness of the arthroscopic management of the stiff elbow. In most cases, it would appear to be an effective tool in the treatment of this disorder.

COMPLICATIONS

In the authors’ initial series, there was a single isolated nerve injury, which was case 12. However, reports by Haapaniemi19 and Miller39 have delineated the further risk of nerve damage. Morrey et al have also presented the risk of elbow arthroscopy in the Mayo Clinic series. They described no permanent neurologic injuries, and had an overall complication rate of approximately 10%, a level that parallels our own experience.29

THE ARTHRITIC ELBOW

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative management includes use of selected Celestone injections and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications and physical therapy. Surgical treatment is indicated only when nonoperative management becomes ineffective and the patient’s pain and functional limitations warrant surgical intervention.*

INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY

Pain and functional impairment refractory to non-operative management would indicate surgery for the arthritic elbow. The age, activity level, patient desires, bone stock, and severity of the deformity dictate the choice between arthroscopic management and total elbow arthroplasty.10,22,56,57

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT—HISTORY

Modern nonprosthetic operative management for arthritis of the elbow dates back to the Outerbridge-Kashiwagi procedure.28 Through a triceps-splitting approach, the olecranon is débrided and a clower drill is used to bore a hole between the olecranon and coronoid fossa, improving both flexion and extension and decreasing symptoms of anterior and posterior impingement. In inflammatory arthritis, resection of the radial head has proved to be beneficial, especially in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Morrey modified the Outerbridge-Kashiwagi procedure by using a Bryan-Morrey approach and elevating the triceps rather than splitting it, believing that this decreased intra-articular adhesions and improved range of motion while allowing transposition of the ulnar nerve.40 Savoie et al54 modified Morrey’s approach to perform the procedure arthroscopically and used the arthroscopic instruments to fenestrate the olecranon and coronoid fossa, resect the radial head as necessary, and remove loose bodies and perform synovectomy with excellent results with a minimum 2-year follow-up.

Cohen et al10 reported on 26 patients managed arthoscopically with excellent pain relief and no complications. Phillips and Strasburger47 reported on 25 patients with similar results. McLaughlin et al37 reported on a group of 36 patients with primary radial sided initiation of damage who responded well to arthroscopic management, including radial head excision in all patients. They isolated a group that they thought were more at risk for early progression of the arthritis and suggested the benefit of earlier excision due to deformity and slight instability. These reports seem to indicate the enduring success of the arthroscopic method for early and mid-stage arthritis and even late-stage arthritic changes in the more active individual in whom an elbow replacement might be contraindicated.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE: AUTHORS’ PREFERRED METHOD

The elbow is entered through a standard proximal anterior medial portal (Box 40-3). The proximal anterolateral portal is established, and the anterior aspect of the elbow joint is evaluated. The tip of the coronoid is evaluated and usually resected (Fig. 40-8A and B). The radial head and radial fossa are evaluated for anterior impingement with flexion. The preoperative evaluation should have formulated a plan as to whether or not the radial head needs to be excised. McLaughlin et al have reported on a subset of post-traumatic arthritic patients in whom the radial column is the initiating factor in the arthritis. In this group, they believed that radial head excision was necessary to prevent progression of the arthritis and also to prevent posterior radiocapitellar impingement that limited extension. In the more common primary arthritic elbow, the radial head may be preserved and only the radial fossa débrided to increase flexion. It is important to make this distinction preoperatively. Radial fossa excision is accomplished with the arthroscope in the proximal anterior medial portal and the shaver in the proximal anterior lateral portal. The excess bone just above the articular rim of the anterior capitellum is removed until the normal cortex is encountered. Flexion of the elbow determines if enough bone has been resected to allow full excursion of the radio-capitellar joint.

If radial head excision is necessary, the anterior aspect of the radial head is resected first in order to avoid penetrating the anterior capsule with possible injury to the posterior interosseous nerve (which lies adjacent to the anterolateral capsule at the level of the radial head and neck). Once the radial head anterior margin has been resected, a protective retractor is placed in the proximal anterior lateral portal to sit between the radial head and the anterior capsule to retract and protect the radial nerve. The burr is then introduced through the soft spot portal, and the radial head is coplaned until a complete resection has been accomplished (Fig. 40-9A and B). In the case of isolated radiocapitellar impingement, the proximal 8 to 10 mm of the radial head may be resected and if the proximal radioulnar joint is involved, the entire radial head can be resected (see Fig. 40-9C).

The surgical focus is then moved to the posterior elbow joint. An inflow canula is left anteriorly to ensure that fluid flows through the gutters and into the posterior compartment. A straight posterior viewing portal is established and also an accessory posterior lateral instrument portal. The olecranon fossa is débrided and three 5-mm drill holes are placed in the olecranon fossa, connecting it to the coronoid fossa. These holes are connected using a burr and enlarged until a fenestration of approximately 1 to 3 cm in diameter is made. This should allow visualization of the anterior structures through the fenestration and evaluation of the coronoid resection can be made. If necessary, additional resection can be accomplished while viewing from this portal. The tip of the olecranon is then excised. Care should be taken to plane medially and laterally to prevent impingement of the medial and lateral aspects of the olecranon on the columns of the distal humerus. In most cases, it is this medial and lateral impingement that limits the extension, not the center of the olecranon. The resection for arthritis might include as much as 1 to 2 cm. This is in contrast to cases with instability, in which only minimal bone should be removed to decrease the risk of exacerbating the instability. Medial gutter spurs are then resected with the suction turned off to prevent injury to the ulnar nerve. The presence of significant spurs may require release of the ulnar nerve by either open or arthroscopic (Fig. 40-10) means. If there is any question, the nerve should be exposed and tracked with the arthroscope or via open technique to both decompress the nerve and decrease the risk of tardy ulnar nerve palsy. The lateral gutter is then evaluated and any debris removed. If a symptomatic posterolateral plica is present, it is resected. This area of the posterior radiocapitellar joint and proximal radioulnar joint is a common area for loose bodies and for synovitis. It must be evaluated in every case. The entire elbow joint is then re-evaluated, completing the procedure.

RESULTS

In a previous study, Nunely et al54 delineated approximately 96% good to excellent results and a minimum 2-year follow-up for the arthritic elbow. This is in a degenerative population in which two thirds of the patients required radial head excision, indicating the efficacy of this procedure for the arthritic elbow. McLaughlin and colleagues37 reported a series of degenerative elbows managed by this technique in which the instigating factor for the arthritis was a radial column injury. Satisfactory results were reported in 36 patients, with no significant complications. Cohen et al,10 Menth-Chiari et al,38 Phillips and Strasburger,47 and Kim and Chin30 reported excellent results with no significant complications in their series of patients. In combining these series, the average arc of motion improved between 41 and 81 degrees, with a significant decrease in pain and improvement in function.

COMPLICATIONS

Most complications involve the presence of persistent drainage from the lateral portals. Recent reviews from the Mayo Clinic and the Mississippi Sports Medicine and Orthopaedic Center (MSMOC) of large series of patients fortunately revealed no permanent neurologic injuries. However, in both series, the overall complication rate was 10%, emphasizing the risks inherent in arthroscopy of the elbow.29,53

1 Aldridge J.M.III, Atkins T.A., Gunneson E.E., Urbaniak J.R. Anterior release of the elbow for extension loss. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2004;86:1955.

2 Andrews J.R., Carson W.G. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1985;1:97.

3 Baker C.L.Jr, Jones G.L. Arthroscopic of the elbow. Am. J. Sports Med.. 1999;27:251.

4 Ball C.M., Meunier M., Galatz L.M., Calfee R., Yamasuchi K. Arthroscopic treatment of post traumatic elbow contracture. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:624.

5 Bede W.B., Lefebvre A.R., Rosman M.A. Fractures of the medial humeral epicondyle in children. Can. J. Surg. 1975;18:137.

6 Burman M.S. Arthroscopy or the direct visualization of joints. A cadaveric study. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1931;13:669.

7 Burman M.S. Arthroscopy of the elbow joint: An experimental cadaveric study. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1932;14:349.

8 Buxton J.D. Ossification in the ligaments of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1938;20:709.

9 Byrd J.W. Elbow arthroscopy for arthrofibrosis after Type I radial head fractures. Arthroscopy. 1994;10:162.

10 Cohen A.P., Redden J.F., Stanley D. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the elbow: A comparison of open and arthroscopic debridement. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:701.

11 Dickson R.A. Reverse dynamic slings. A new concept in the treatment of post-traumatic elbow flexion contractures. Injury. 1976;8:35.

12 Ferlic D.C., Patchett C.E., Clayton M.L., Freeman A.C. Elbow synovectomy in rheumatoid arthritis: Long-term results. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1987;220:119.

13 Freehafer A. Flexion and supination deformities of the elbow in tetraplegics. Paraplegia. 1977;15:221.

14 Gallay S.H., Richards R.R., O’Driscoll S.W. Intra-articular capacity and compliance of stiff and normal elbows. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:9.

15 Gendi N.S., Axon J.M., Carr A.J., Pile K.D., Burge P.D., Mowat A.G. Synovectomy of the elbow and radial head excision in rheumatoid arthritis: Predictive factors and long-term outcome. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1997;79:918.

16 Glynn J., Niebauer J.J. Flexion and extension contractures of the elbow. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1976;177:289.

17 Green D.P., McCoy H. Turn buckle orthotic correction of elbow flexion contractures after acute injuries. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1979;61A:1092.

18 Gutierre L.S. A contribution to the study of the limiting factors of elbow extension. Acta Anat. 1964;56:146.

19 Haapaniemi T., Berggren M., Adolfsson L. Complete transection of the median and radial nerves during arthroscopic release of post-traumatic elbow contracture. Arthroscopy. 1999;10:784.

20 Hagena F.W.. Synovectomy of the elbow. Hama-lainen M., Hagena F.W., editors. Rheumatoid Surgery of the Elbow, vol 15. Karger, Basel, Switzerland, 1991;6.

21 Hahn M., Grossman J.A. Ulnar nerve laceration as a result of elbow arthroscopy. J. Hand Surg. (Br.). 1998;23:109.

22 Hamalainen M., Ikavalko M., Kammonen M.. Epidemiology of the elbow joint involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Hamalainen M., Hagena F.W., editors. Rheumatoid Surgery of the Elbow, vol 15. Karger, Basel, Switzerland, 1991;1.

23 Horiuchi K., Momohara S., Tomatsu T., Inoue K., Toyama Y. Arthroscopic synovectomy of the elbow in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2002;84:342.

24 Huang T.T., Blackwell S.J., Louis S.R. Ten years of experience in managing patients with burn contractures of the axilla, elbow, wrist and knee joints. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1978;61:70.

25 Husband J.B., Hastings H. The lateral approach for operative release of post-traumatic contracture of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A:1353.

26 Jones G.S., Geissler W.B. Complications of Minimally Displaced Radial Head Fractures. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Orthopaedie Surgeons, 1993.

27 Jones G.S., Savoie F.H. Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:277.

28 Kashiwaga D. Osteoarthritis of the elbow joint: intra-articular changes and the special operative procedure. Outerbridge-Kashiwaga method. In: Keshiwaga D., editor. Elbow Joint. New York: Elsevier; 1985:177.

29 Kelly E.W., Morrey B.F., O’Driscoll S.W. Complication of elbow arthroscopy. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2001;83A:25.

30 Kim S.J., Shin S.J. Arthroscopic treatment for limitation of motion of the elbow. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2000;375:140.

31 Lapner P.C., Leith J.M., Regan W.D. Arthroscopic debridement of the elbow for arthrofibrosis resulting from nondisplaced fracture of the radial head. Arthroscopy. 2005;12:1492.

32 Lee B.P., Morrey B.F. Arthroscopic synovectomy of the elbow for rheumatoid arthritis: A prospective study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1997;79:770.

33 Lonner J.H., Stuchin S.A. Synovectomy, radial head excision, and anterior capsular release in stage III inflammatory arthritis of the elbow. J. Hand Surg. (Am.). 1997;22:279.

34 Maenpaa H., Kuusela P., Lehtinen J., Savolainen A., Kautiainen H., Belt E. Elbow synovectomy on patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2003;412:65.

35 Maenpaa H.M., Kuusela P.P., Kaarela K., Kautiainen H.J., Lehtinen J.T., Belt E.A. Reoperation rate after elbow synovectomy in rheumatoid arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:480.

36 Makai F., Chudacek J.. Long-term results of synovectomy of the elbow with excision of the radial head in rheumatoid arthritis. Hamalainen M., Hagena F.W., editors. Rheumatoid Surgery of the Elbow, vol 15. Karger, Basel, Switzerland, 1991;22.

37 McLaughlin R.E., Savoie F.H.III, Field L.D., Ramsey J.R. Arthroscopic treatment of the arthritic elbow due to primary radiocapitellar arthritis. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:63.

38 Menth-Chiari W.A., Ruch D.S., Pochling G.G. Arthroscopic excision of the radial head: Clinical outcome in 12 patients with post traumatic arthritis after fracture of the radial head and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:918.

39 Miller C.D., Jobe C.M., Wright M.H. Neuroanatomy in elbow arthroscopy. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4:168.

40 Morrey B.F. Primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow: treatment by ulnohumeral arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74B:409.

41 Morrey B.F., An K.N. Articular and ligamentous contributions to the stability of the elbow joint. Am. J. Sports Med. 1983;11:315.

42 Morrey B.F., Askew L.J., Chao E.W. A biomechanical study of normal functional elbow motion. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1981;63A:872.

43 Nguyen D., Proper S.I., MacDermid J.C., King G.J., Faber K.J. Functional outcomes of arthroscopic capsular release of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:842.

44 Nowicki K.D., Shall L.M. Arthroscopic release of a posttraumatic flexion contracture in the elbow: a case report and review of the literature. Arthroscopy. 1992;8:544.

45 O’Driscoll S.W., Morrey B.F. Arthroscopy of the elbow: diagnostic and therapeutic benefits and hazards. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1992;74:84.

46 Papilion J.D., Neff R.S., Shall L.M. Compression neuropathy of the radial nerve as a complication of elbow arthroscopy: A case report and review of literature. Arthroscopy. 1988;4:284.

47 Phillips B.B., Strasburger S. Arthroscopic treatment of arthrofibrosis of the elbow joint. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:38.

48 Poehling G.G., Whipple T.L., Sis O.L., Goldman B. Elbow arthroscopy, A new technique. Arthroscopy. 1989;5:222.

49 Protzman R.R. Dislocation of the elbow joint. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1978;60A:539.

50 Roberts P.H. Dislocation of the elbow. Br. J. Surg. 1969;56:806.

51 Ruch D.S., Poehling G.G. Anterior interosseous nerve injury following elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:756.

52 Saito T., Koschino T., Okamoto R., Horiuchi S. Radial synovectomy with muscle release for the rheumatoid elbow. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1986;57:71.

53 Savoie F.H.III, Field L.D. Complications of elbow arthroscopy. In: Savoie R.H.III, Field L.D., editors. Arthroscopy of the Elbow. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996:151.

54 Savoie F.H.III, Nunley P.D., Field L.D. Arthroscopic management of the arthritic elbow: indications, technique, and results. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:214.

55 Sherk H.H. Treatment of severe rigid contractures of cerebral palsy to upper limbs. Clin. Orthop. 1977;125:1151.

56 Steinmann S.P. Elbow arthroscopy. J. Am. Soc. Surg. Hand. 2003;3:199.

57 Steinman S.P., King G.J.W., Savoie F.H.III. Arthroscopic treatment of the arthritic elbow. Inst. Course Lect. 2006;55:109.

58 Stothers K., Day B., Regan W.R. Arthroscopy of the elbow: anatomy, portal sites, and a description of the proximal lateral portal. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:449.

59 Thomas M.A., Fast A., Shapiro D. Radial nerve damage as a complication of elbow arthroscopy. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1987;215:130.

60 Thompson H.S., Garcia A. Myositis ossificans: aftermath of elbow injuries. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1976;50:129.

61 Timmerman L.A., Andrews J.R. Arthroscopic treatment of post traumatic elbow pain and stiffness. Am. J. Sports Med. 1994;22:230.

62 Tucker K. Some aspects of post-traumatic elbow stiffness. Injury. 1997;9:216.

63 Tulp N.J., Winia W.P. Synovectomy of the elbow in rheumatoid arthritis: Long-term results. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1989;71:664.

64 Urbaniak J.R., Hansen P.E., Beissinger S.F., Aitken M.S. Correction of post-traumatic flexion contracture of the elbow by anterior capsulotomy. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1985;67A:1160.

65 Wilner P. Anterior capsulectomy for contractures of the elbow. J. Int. Coll. Surg. 1948;11:359.

66 Woods D.A., Williams J.R., Gendi N.S., Mowat A.G., Burge P.D., Carr A.J. Surgery for rheumatoid arthritis of the elbow: A comparison of radial-head excision and synovectomy with total elbow replacement. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:291.

67 Wright T.W., Glowczewskie F.Jr, Cowin D., Wheeler D.L. Ulnar nerve excursion and strain at the elbow and wrist associated with upper extremity motion. J. Hand Surg. (Am.). 2001;26:655.