CHAPTER 45 Arthroscopic Diagnosis of Carpal Ligament Injuries with Distal Radius Fractures

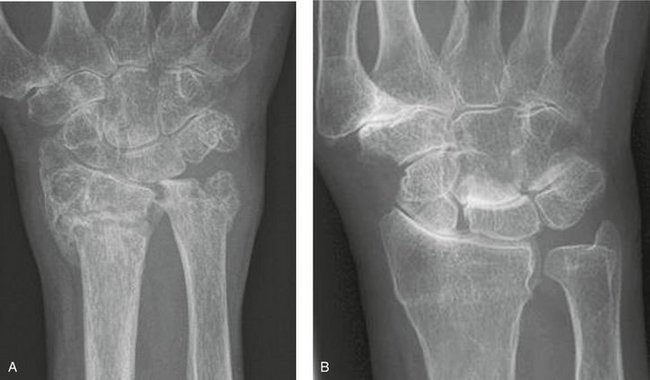

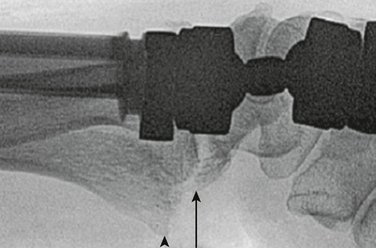

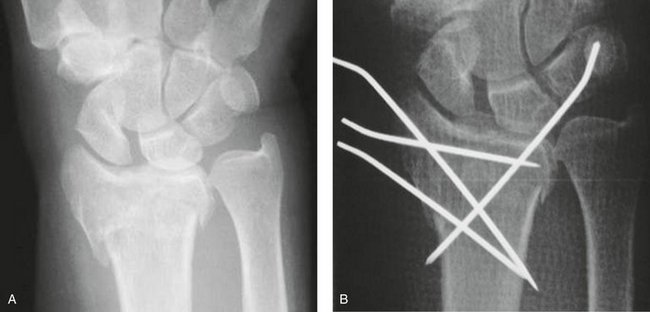

Carpal ligament injuries have been found in association with distal radius fractures (Fig. 45-1)1–3 and with scaphoid and other fractures (Fig. 45-2).4,5 In contrast to these injuries, which sometimes are radiographically visible, there are other associated soft tissue injuries involving the median nerve, the radial artery (Fig. 45-3), or flexor tendons with ruptures. In addition, numerous articles have highlighted the extent of associated cartilage and ligament injuries with displaced distal radius fractures, especially in nonosteoporotic individuals.6–10 These injuries occasionally can be found with fluoroscopy or magnetic resonance imaging,11 but are most often found when the distal radius fracture is managed with wrist arthroscopy as an adjunct.

FIGURE 45-1 A and B, Scapholunate dissociation found before and after treatment of displaced distal radius fracture.

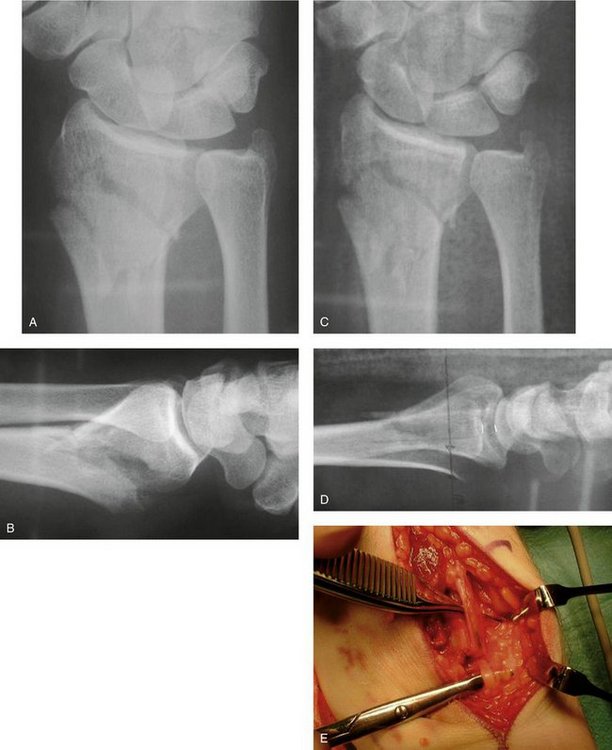

FIGURE 45-3 A to D, Dorsally dislocated distal radius fracture, which after manipulation still had an unacceptable displacement. E, At open reduction with a palmar approach, the radial artery was injured and interposed in the fracture.

There has been a tendency to overlook these injuries, in contrast to the awareness of similarly important injuries in the lower extremity (Fig. 45-4). To minimize the impact of missed associated injuries, we have to improve our knowledge about them and improve our management of distal radius fractures. We should try to define, classify, and treat the devastating “syndesmosis” injuries of the wrist as soon as possible (Fig. 45-5).

FIGURE 45-4 Syndesmosis injury in an ankle without fracture. This devastating ligament injury is defined and classified and receives full treatment and attention in the orthopaedic community.

At the Time of the Fracture When Initial Radiographs Are Reviewed

There is an obvious difference between patients and their needs, which can be clearly seen already at the initial presentation, where a range of associated, but preexisting conditions can be found (Fig. 45-6). Sometimes the associated injuries are obvious, but in most situations the soft tissue injuries are not evident at all (Fig. 45-7). We then either have to find them or have to exclude that such associated injuries exist.

At the Initial Presentation, at the Fracture Clinic during the First Week, and at the 10- to 14-Day Follow-up

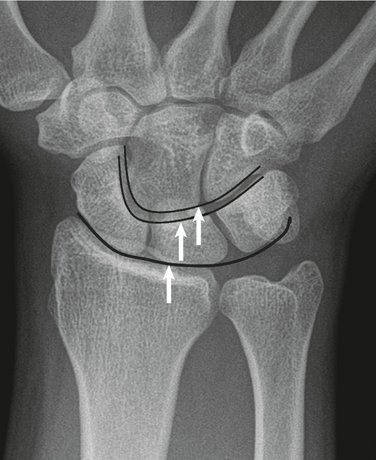

The radiographs should always be reviewed with the utmost scrutiny regarding degree of displacement, including the ulnar styloid fracture, which may indicate an ulnoradial ligament detachment (peripheral triangular fibrocartilage complex [TFCC] injury) (Fig. 45-8). The three carpal arcs of Gilula12 (Fig. 45-9), which are indicative of intercarpal ligament injury, always should be checked.

FIGURE 45-9 The three carpal lines of Gilula (arrows), which, if disrupted, reveal an intercarpal ligament injury.

The most important prognostic factor for a bad outcome after distal fractures is the ulnar-positive variance13; there is a 2.5 times increased risk for a bad outcome in nonosteoporotic individuals if the ulnar-positive variance is more than 2 mm. An ulnar-positive variance more than 2 mm also has been shown to give a 3.9 relative risk (95% confidence interval 1.1 to 13.3; P = .01) of a grade 3 to 4 scapholunate (SL) ligament injury (Lindau classification system).7,14

The second most important prognostic factor is articular involvement; an intra-articular incongruency of more than 1 mm leads to osteoarthritis).15 An intra-articular fracture also has been shown to be a potentially important factor for a poor outcome in nonosteoporotic patients.13 Fractures that have a partial intra-articular (AO type B) or combined extra-articular and intra-articular involvement (AO type C) have been shown to increase the risk for a Lindau grade 3 to 4 SL ligament injury7,14 at the time of injury and to increase the risk for radiographic dynamic or static SL dissociation 1 year after the trauma.14

Patient age, metaphyseal comminution of the fracture, and ulnar variance have been shown to be the most consistent predictors of radiographic outcome.13,16 Dorsal angulation and radial length have not been shown to be associated with a bad outcome,13,16 which may explain why the AO and Frykman classifications17 have failed to correlate with the outcome.18

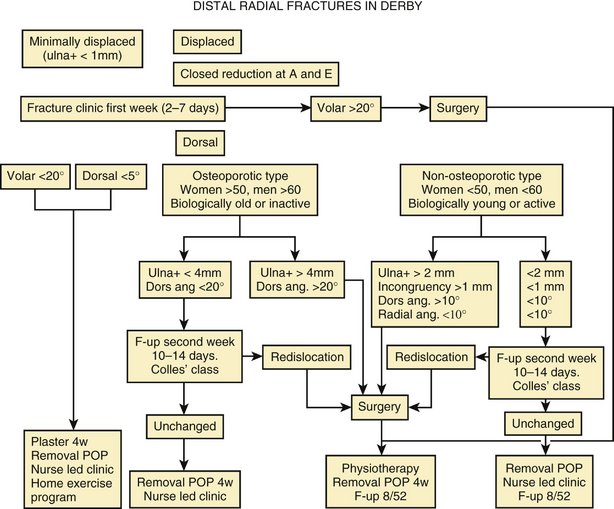

An evidence-based algorithm can be very helpful in managing distal radius fractures (Fig. 45-10), where the search for associated injuries is added to the general decisions regarding management of the fracture. There is a special emphasis in the algorithm on the differences between nonosteoporotic and osteoporotic patients.19 The differences are in regard to fracture pattern, associated injuries, treatment alternatives, and outcome, which reflect the future need of patients for their wrists after the injury. Initial assessment also should address the potential risks not obvious on an x-ray, where palmarly displaced fragments especially can cause radial artery injuries, flexor tendon ruptures, or median nerve entrapments (carpal tunnel syndrome).

At the Time of Surgical Treatment

If surgical treatment is necessary according to the initial assessments and the pathways of the evidence-based algorithm (see Fig. 45-10), we have the golden opportunity to assess, find, and treat all injured parts of the wrist.

Arthroscopy—the Gold Standard of Detecting and Treating Associated Injuries

If surgery is necessary, there is a paramount reason to consider arthroscopy as an adjunct to the final treatment. General arthroscopic technique is applied with the following guidelines2:

A standard setup is used with a mobile cart with a monitor at the foot end of the patient. Arthroscopy can be done as either a standard vertical setup or with horizontal arthroscopy,20 which gives the surgeon several options for additional treatment after the initial arthroscopy has been done.

After the joint has been cleared, the arthroscopy-assisted reduction starts by disimpacting the fragments followed by elevating the fragments, securing the reduction with Kirschner wires (K-wires) or percutaneous fixation, and finally verifying the reduction. The joint surface should be reduced by starting with the ulnar fragments because they cause a “double joint incongruency” (i.e., the radiocarpal joint and the distal radioulnar joint [DRUJ]).2 Various techniques have been described for special fracture situations.

The final fixation of the fragments can be done with a “closed” reduction of the ulnar fragments with a mini-invasive reduction and percutaneous pinning according to the technique recommended by Geissler and colleagues.21 Kapandji intrafocal pinning22 is a useful option in selected cases. Another option is an open reduction of ulnar-sided fractures, which can be part of managing a combined intra-articular and extra-articular fracture. This can be fixed according to the surgeon’s preference with various types of dorsal or palmar plates, including the currently popular locking plates. The final fixation of the extra-articular components of the fracture is facilitated with the horizontal position at the initial arthroscopy, which is converted easily into the final open fixation.20

Ulnar Styloid Fractures May Represent a Destabilizing Injury

Fracture of the ulnar styloid has been found with and without a destabilizing injury to the ulnoradial ligament (peripheral tear of the TFCC).7,9 af Ekenstam and coworkers23 did not find any statistical difference regarding either redislocation or healing of the styloid or functional outcome of the distal radial fracture. A fracture of the ulnar styloid has not been associated with a development of DRUJ laxity 1 year after the fracture.24 Consequently, an ulnar styloid fracture is not a good indicator for severity, as stated by Frykman,17 which probably explains why the Frykman classification17 has failed to correlate to final outcome.18

Ulnar styloid fracture at its base with initial displacement more than 2 mm should be treated with open reduction and internal fixation (see Fig. 45-7A).21,25 Use of open reduction and internal fixation is even more important if the dislocation is in a radial direction (detaching the ulnoradial ligament; see Fig. 45-8B) than in an axial, distal direction (detaching the ulnotriquetral collateral ligament; see Fig. 45-7A). The fixation can be done with a single K-wire,26,27 tension band wiring,21 a wire loop/suture,26 or screw fixation.28

Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex Tears Are the Most Common Destabilizing Injuries

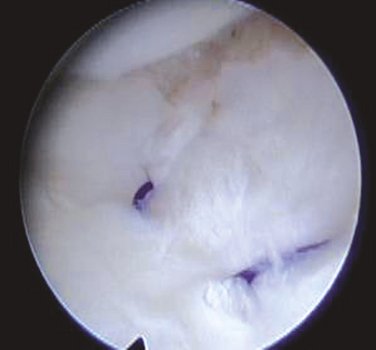

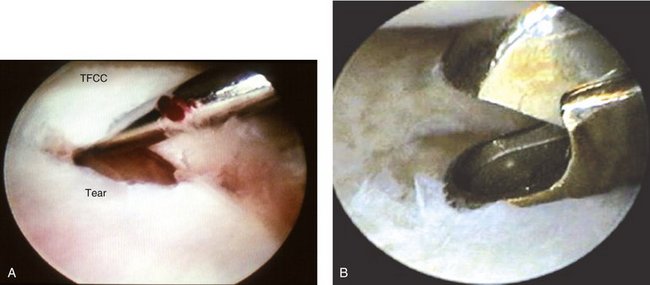

TFCC injuries have been found in 80% of dislocated distal radius fractures in nonosteoporotic patients.7 They have been associated with shortening (ulna positive) and dorsal angulation of the radius fracture.9 The most important of these injuries are the tears to the ulnoradial ligaments (peripheral TFCC tears), which have been shown to cause laxity 1 year after the fracture.24 Peripheral TFCC tears probably should be repaired, which can be done with an arthroscopically assisted technique and reattachment to the fovea (Fig. 45-11).2 A central perforation tear of the TFCC is stable and can be débrided with a suction punch (Fig. 45-12).2

Scapholunate Ligament Injury Leads to Scapholunate Dissociation

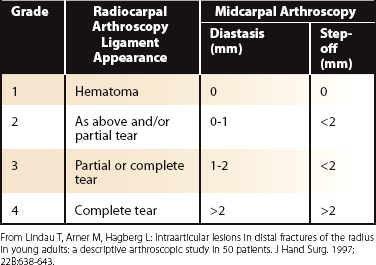

SL ligament tears have been found in 50% of dislocated distal radius fractures in nonosteoporotic patients.7 At radiocarpal arthroscopy, the ligament appearance can be assessed, and with comparison of the midcarpal appearance the diastasis and step-off can be measured to classify the grade of SL injury according to Geissler29 or Lindau7 (Table 45-1). With this assessment, we have shown that a grade 3 to 4 SL ligament injury (Lindau classification7 [see Table 45-1]) that was found at the time of the distal radial fracture, but not treated, leads to radiographic dissociation 1 year after the injury.14

TABLE 45-1 Classification System for Interosseous Scapholunate and Lunotriquetral Ligament Injuries and Mobility of the Joints

In the absence of prospective randomized studies, it is reasonable to treat grade 3 injuries with reduction of the displaced carpal bones by positioning K-wires in the lunate and the scaphoid. The reduction of the incongruent SL joint is monitored in the midcarpal joint, and the K-wires are secured into the bones. Fluoroscopy can verify the reduction and fixation.2 The pins should be kept for 6 weeks.

The results with the arthroscopy-assisted technique are encouraging; Whipple30 showed that 33 of 40 patients maintained reduction and relief of symptoms if the injury was less than 3 months and the gap was less than 3 mm. In contrast, if there was more than 3 months and more than 3 mm of gap, the improvement occurred in only 21 of 40 patients. Time is consequently of the essence in finding these injuries, and if they are found in time, the results are good in 85% after 2 to 7 years.30 No further long-term studies have been done in this area. Finally, it also seems reasonable to assume that grade 4 injuries, especially injuries with a dissociation already on the trauma films, probably should be treated with an open repair.2

Lunotriquetral Ligament Injuries Are Uncommon

Lunotriquetral ligament tears have been found in 10% of dislocated distal radius fractures in nonosteoporotic patients.7 There are no long-term studies in this area, but complete tears with severe mobility (grade 4 [see Table 45-1]7) probably have to be pinned for 6 weeks.2 Pinning of acute lunotriquetral tears has shown to have a good outcome with 16 of 20 patients excellent or good after  years and 18 of 20 with improved grip strength.31

years and 18 of 20 with improved grip strength.31

Cartilage Injuries Lead to Osteoarthritis

Subchondral hematoma and cartilage avulsions have been found in one third of patients with dislocated fractures among nonosteoporotic patients.7 These lesions result in radiographic subchondral bone plate changes and osteoarthritis after 1 year.32 The implication is that subchondral hematoma after injury is a possible explanation of development of osteoarthritis in other joints. There is currently no treatment other than débridement for these injuries. The most tempting, but unproven, option would be the microfracture treatment used in similar injuries in the knee. If found, these cartilage injuries may lead, however, to changes in treatment in the sense that a comminuted intra-articular fracture might be treated with a partial wrist fusion. It also would give the surgeon an awareness of an expected bad outcome.

Other Options at the Time of Surgical Treatment

In the absence of arthroscopy, a fluoroscopic assessment, including stress views, before reduction and fixation is mandatory to plan the surgical approach appropriately. Fluoroscopy is done with examination with an ulnar and radial deviation to see any gapping between the carpal bones. A traction view also may be tried to see whether the Gilula lines12 are disrupted. The DRUJ is difficult to assess before the distal radius fracture has been stabilized.

After reduction and fixation of the distal radius fracture, a new assessment of the intercarpal ligaments (see Fig. 45-1) and DRUJ stability (see Fig. 45-7B and C) should be done. The focus should not be on the fracture alone. One should try to avoid overdistracting the soft tissues if external fixation is used (Fig. 45-13), and one should try to understand if a fragment may represent the insertion of a crucial radiocarpal stabilizing ligament (Fig. 45-14).

At a Later Follow-up about 3 Months after the Fracture

At this stage, one should reassess everything, including all radiographs through the treatment; do a thorough clinical examination; and probably have new x-rays taken. At the clinical examination, one should look for signs of sagging of the hand compared with the distal forearm and look out for a prominent ulnar head (Fig. 45-15). This may represent an avulsed dorsal radiotriquetral ligament causing the sagging lateral view and potentially development of a midcarpal instability. The DRUJ should be examined; the stability test has been shown to be useful and reproducible.33 Additional radiographs, including stress views such as clenched fist views, should be considered and thereafter possibly arthrography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging depending on access to these imaging modalities. The final option to understand fully the reasons for complicating symptoms and signs 3 months after a distal radius fracture is to do a wrist arthroscopy.

Conclusion

A fall on an outstretched hand may lead to a variety of injuries to the wrist—ranging from a sprain to a full-blown perilunate dislocation (see Fig. 45-7A). There are degrees of injuries and significance in the Mayfield34 mechanism causing a variety of injuries in the wrist (see Figs. 45-1, 45-7A, and 45-8B). It is our task to assess early and decide what kind of injury we have to treat in every case.

We should look for prognostic markers on the initial radiographs, where an ulnar-positive variance more than 2 mm and an intra-articular fracture marks a higher risk of more severe fractures and more associated ligament injuries. This evaluation should be repeated at every follow-up in fracture clinics during the first week and at the 10- to 14-day follow-up. At these early assessments, there is an important role for an evidence-based algorithm (see Fig. 45-10) showing the pathway for each patient according to the appearance of the fracture with an emphasis on whether there are signs of clinical osteoporosis.

1 Cooney WP3rd, Dobyns JH, Linscheid RL. Complications of Colles’ fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:613-619.

2 Lindau T. The role of wrist arthroscopy in distal radial fractures. Atlas Hand Clin. 2001;6:285-306.

3 Mudgal CS, Jones WA. Scapho-lunate diastasis: a component of fractures of the distal radius. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1990;15:503-505.

4 Fisk GR. Carpal instability and the fractured scaphoid. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1970;46:63-76.

5 Vender MI, Watson HK, Black DM, et al. Acute scaphoid fracture with scapholunate gap. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1989;14:1004-1007.

6 Geissler WB, Freeland AE, Savoie FH, et al. Intracarpal soft-tissue lesions associated with an intra-articular fracture of the distal end of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:357-365.

7 Lindau T, Arner M, Hagberg L. Intraarticular lesions in distal fractures of the radius in young adults: a descriptive arthroscopic study in 50 patients. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1997;22:638-643.

8. Lindau T. Distal radial fractures and effects of associated ligament injuries. Lund: University of Lund; 2000.

9 Richards RS, Bennett JD, Roth JH, et al. Arthroscopic diagnosis of intra-articular soft tissue injuries associated with distal radial fractures. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1997;22:772-776.

10 Shih JT, Lee HM, Hou YT, et al. Arthroscopically-assisted reduction of intra-articular fractures and soft tissue management of distal radius. J Asia-Pacific Fed Soc Surg Hand. 2001;6:127-135.

11. Spence LD, Savenor A, Nwachuku I, et al. MRI of fractures of the distal radius: comparison with conventional radiographs. Skeletal Radiol. 1998;27:244-249.

12 Gilula LA. Carpal injuries: analytic approach and case exercises. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;133:503-517.

13. Beumer A, Adlercreutz C, Lindau T: Early prognostic factors for a bad outcome in non-osteoporotic distal radius fractures. Presented as a poster at IFSSH meeting, Sydney, Australia, 2007.

14 Forward D, Lindau T, Melsom D. Intercarpal ligament injuries associated with fractures of the distal radius: arthroscopic assessment and 12 month follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2334-2340.

15 Knirk JL, Jupiter JB. Intra-articular fractures of the distal end of the radius in young adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:647-659.

16. Mackenney PJ, McQueen MM, Elton R. Prediction of instability in distal radial fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1944-1951.

17 Frykman G. Fracture of the distal radius including sequelae, shoulder-hand-finger syndrome, disturbance in the distal radio-ulnar joint and impairment of nerve function. Acta Orthop Scand. 1967;38(Suppl 108):83-88.

18 Flinkkilä T, Raatikainen T, Hämälainen M. AO and Frykman’s classifications of Colles’ fracture: no prognostic value in 652 patients evaluated after 5 years. Acta Orthop Scand.. 1998;69:77-81.

19 Lindau T, Aspenberg P, Arner M, et al. Fractures of the distal forearm in young adults: an epidemiologic description of 341 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70:124-128.

20 Lindau T. Wrist arthroscopy in distal radial fractures with a modified horizontal technique. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(1):E5.

21 Geissler WB, Fernandez DL, Lamey DM. Distal radioulnar joint injuries associated with fractures of the distal radius. Clin Orthop. 1996;327:135-146.

22 Kapandji A. [Internal fixation by double intrafocal plate: functional treatment of non articular fractures of the lower end of the radius] (author’s transl). Ann Chir. 1976;30(11-12):903-908.

23 af Ekenstam F, Jacobsson OP, Wadin K. Repair of the triangular ligament in Colles’ fracture: no effect in a prospective randomized study. Acta Orthop Scand. 1989;60:393-396.

24 Lindau T, Adlercreutz C, Aspenberg P. Peripheral tears of the triangular fibrocartilage complex cause distal radioulnar joint instability after distal radial fractures. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2000;25:464-468.

25 May MM, Lawton JN, Blazar PE. Ulnar styloid fractures associated with distal radius fractures: incidence and implications for distal radioulnar joint instability. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2002;27:965-971.

26 Mikic DJZ. Treatment of acute injuries of the triangular fibrocartilage complex associated with distal radioulnar joint instability. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1995;20:319-323.

27 Shaw JA, Bruno A, Paul EM. Ulnar styloid fixation in the treatment of posttraumatic instability of the radioulnar joint: a biomechanical study with clinical correlation. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1990;15:712-720.

28 Hauck RM, Skahen JIII, Palmer AK. Classification and treatment of ulnar styloid nonunion. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1996;21:418-422.

29 Geissler WB. Arthroscopically assisted reduction of intra-articular fractures of the distal radius. Hand Clin. 1995;11:19-29.

30 Whipple TL. The role of arthroscopy in the treatment of scapholunate instability. Hand Clin. 1995;11:37-40.

31 Osterman AL, Seidman GD. The role of arthroscopy in the treatment of lunatotriquetral ligament injuries. Hand Clin. 1995;11:41-50.

32 Lindau T, Adlercreutz C, Aspenberg P. Cartilage injuries in distal radial fractures. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74:327-331.

33 Lindau T, Runnquist K, Aspenberg P. Patients with laxity of the distal radioulnar joint after distal radial fractures have impaired function, but no loss of strength. Acta Orthop Scand. 2002;73:151-156.

34. Mayfield JK, Johnson RP, Kilcoyne RF. The ligaments of the human wrist and their functional significance. Anat Rec. 1976;186:417-428.